DECEMBER 2010

Click title to jump to review

HARPS AND ANGELS music by Randy Newman, conceived by Jack Viertel | Mark Taper Forum

MAESTRO-THE ART OF LEONARD BERNSTEIN by Hershey Felder | Geffen Playhouse

Ready for prime time

Randy Newman's song catalogue has again been picked over to create a stage show. Harps and Angels, in its Mark Taper Forum world premiere (through December 22), reminds us once more of Newman's special place in popular music. A rock era singer-songwriter who fashioned stinging satire and sweeping soundtracks, his signature was lyrics sung by a narrator who was not only unreliable, but often reprehensible.

Jerry Zaks directs the new musical, which was conceived by Jack Viertel of Broadway's Jujamcyn productions. Musical staging is by Warren Carlyle, with Newman's longtime musical director Michael Roth handling arrangements and running the band each show. David O worked with Roth on orchestrations.

Unfortunately, while there are occasional moments that add something to the original version, there is not a lot of imagination present in this production. And, for a show that only opened a week ago, there is a decided lack of excitement – not to mention brashness. It all feels a little too polite, like an old television comedy show with a half-dozen versatile regulars who this week salute Randy Newman. While all extremely talented, none – with one exception here – seems born to the music, or able to own these songs down in the bones. It's a fine showcase for Mr. Newman, if you don't mind looking through overly tempered glass.

Songbook musicals generally take the form of a revue of the writer's hits mixed with noteworthy tunes audiences may have missed, or a narrative in which the songs are arranged to support a story line. In the mid-'80s, Des McAnuff launched the revuew Maybe I'm Doing It Wrong, and a decade ago, Roth and Newman worked with South Coast Repertory's Jerry Patch to attempt the semi-biographical Education of Randy Newman. In Harps, we're back to the revue format, with songs vaguely arranged to show progression through life. (An actor announces in the second song, "I was born right here," and the same actor, now playing an old man, lies in a hospital bed in the second to the last song.)

The talented company assembled by Zaks are led by Katey Sagal (best known for her role as Peg Bundy on "Married With Children") and Michael McKean (best known for comedy film gems such as Best in Show and the music business parodies, Spinal Tap, about hard rock, and A Mighty Wind, about folk). The others are Ryder Bach, Storm Large, Adriane Lenox, and Matthew Saldivar.

The women all have strong voices. The men less so. Though Sagal seems capable of the big Broadway vocal, she never seems to tear into a song. Same thing, from the rock vocal direction, with Large (though her table-turning rendition of "Leave Your Hat On" gets as close as anything, and is a highlight). Lenox manages to make the most of every song. Even a ditty like "You've Got a Friend in Me" can tug at the heart. When all three sing together, as in "Rollin," it shows how excellent the voices really are. Still, sweet harmonies (and they are sweet, as sweet as the water nymphs in O' Brother . . . , and that's saying something) cannot make up for the missing roughness.

Of the men, McKean takes the older, Newmanesque characters and presents them genially, even casually. As a result, his best effort – and, not surprisingly, the most "produced" number – is his wonderful "Opry-fied" version of "Big Hat, No Cattle". But, he is nearly as casual in "Shame," which Angelenos know from Education actor Gregg Henry's version in 2000, can be a rocking episode of wizened lechery.

The other two singers, Bach and Saldivar, are adequate if unexciting. Saldivar does well with the subtle ironies of the beautiful "Marie," in which a man pours out his heart about his love, revealing the faults in him he has no intention of changing.

Still, rising above it all are the songs. Anytime the great man can be given a forum for his peculiar brand of peculiarity, it's another perfect day in L.A. And, his willingness to get on board with a few video appearances – and to comb his hair first! – show he's still willing to pour out his heart to us, and thankfully not change his intentions. However, finding the right format for the stage continues to elude him. At least with Zaks restrained direction and a cast more prime time than primal.

top of page

HARPS AND ANGELS

music and lyrics by RANDY NEWMAN

conceived by JACK VIERTEL

directed by JERRY ZAKS

musical staging by WARREN CARLYLE

MARK TAPER FORUM

November 10-December 22, 2010

(Opened 11/21, Rev’d 11/26)

CAST Ryder Bach, Storm Large, Adriane Lenox, Michael McKean, Katey Sagal, Matthew Saldivar u/s Graham Fenton, Christa Jackson, Andy Taylor, Nell Teare

MUSICIANS Michael Roth, conductor/piano; Glen Berger, woodwinds; Robert Payne, trombone; Sid Page, violin; Paul Viapiano, guitar/keyboard; Ken Wild, bass; Bernie Dresel, drums/percussion; Dave Manning, synthesizer programming

PRODUCTION Stephan Olson, set; Stephanie Kerley Schwartz, costumes; Brian Gale, lights; Philip G. Allen, sound; Marc I. Rosenthal, projections; Michael Roth, music direction/arrangements; David O/Michael Roth, orchestrations; Nadia DiGiallonardo, music constultant/add'l arrangements; David S. Franklin/Nate Genung, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

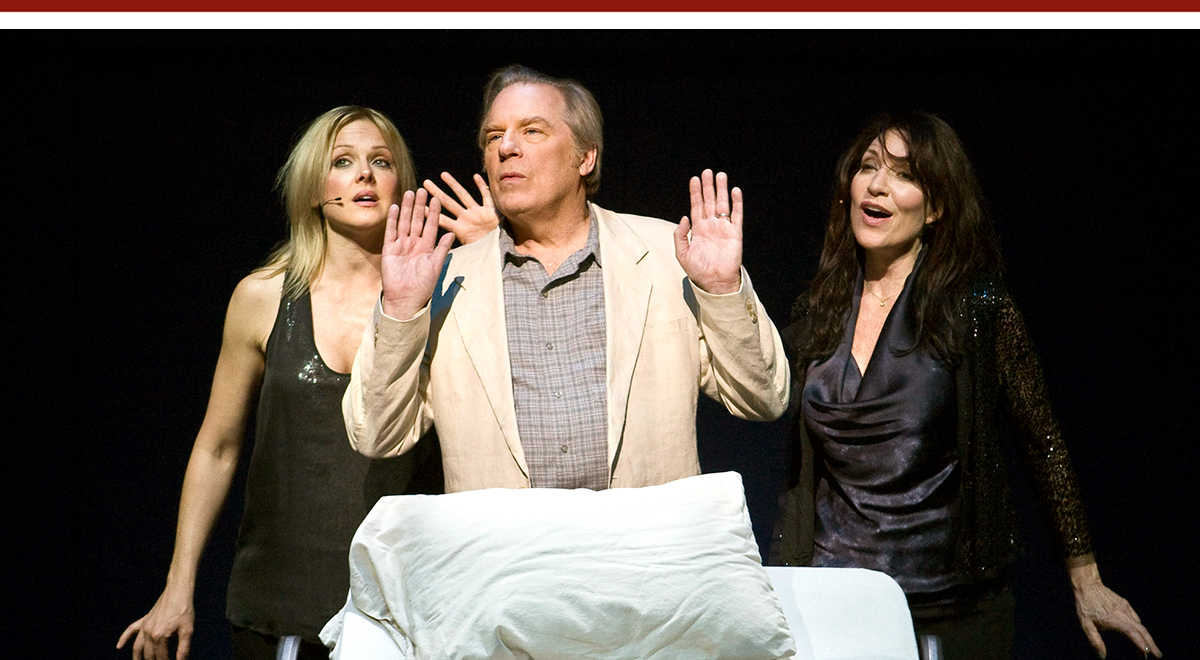

Storm Large, Michael McKean and Katey Sagal, top; inset: Adriane Lenox

Craig Schwartz

In the key of Felder

Hershey Felder and Joel Zwick, the writer-performer and director whose Composers Sonata series of hybrid recital-biographies already included Chopin, Beethoven and Gershwin, add the series' most contemporary, most captured on film, and most conflicted character in Maestro: The Art of Leonard Bernstein, now at the Geffen Playhouse (through December 12).

It may also be their best.

Having not seen the Chopin, I can only compare Maestro to the Gershwin, which was very good, and Beethoven, which was less successful, due to a greater portion of the show given over to piano recital. Mr. Felder is extremely proficien, but lacking that x-factor that distinguishes the world-class pianists who can command a Chandler or Disney Hall engagement.

In Gershwin, like Maestro, Felder felt great kinship with a 20th Century Jewish artist touched by tragedy. The tragedy of Gershwin was that he died in his 30s with what surely would have been more masterpieces left unpenned. "Tragedy" may be too strong for Bernstein's problem, though in Maestro Felder successfully makes what might otherwise be shrugged off as an ironic twist come through as a personal torment. Despite the monumental achievement of becoming the world’s most famous and telegenic conductor, Bernstein failed to be recognized as a great composer. Historians may argue the point, but Felder uses Bernstein's own feeling of falling short to give the Maestro's self-observance the kind of melancholy that, on a grander scale, drove Salieri's observance of Mozart in Amadeus.

In addition to creating that personal tension within the narrator, and delivering it muffled with subtle self-denial, Maestro succeeds on several other levels. It hangs on a story that has worked in this country as far back as Jolson's The Jazz Singer, and probably back to Biblical times (though that father-son rift would have likely been over sacrificing much more than musical dreams). This, of course, is the tale of the boy breaking with the father's traditions to become his own man. And, just as importantly, the show has achieved the right balance of piano pieces and personal profile.

In structuring these plays, Felder’s spine follows the artist's chronology. Maestro gives us first a timeline of Bernstein's achievements and then goes back and fills it in with details, including his personal life with his wife, Felicia, and three children. The one-man show has Felder playing Bernstein, with a single, causal costume, a bushy salt-and-pepper wig. Francois-Pierre Couture's simple set blends backstage and performance space, with a large, frayed piece of manuscript as an upstage projection screen that is filled with historic images by designer Andrew Wilder. Hershey moves from piano bench to leather arm chair, and between performer and teacher. He recalls his years doing Youth Concerts packed with easy-to-understand lessons, gives his take on compositional elements from the eight- and 32-bar song structure to the Phrygian scale, and provides much more insight into both the man and music in general.

We also meet a number of the 20th Century's major musical figures through Bernstein's personal connections, which provides insight into these famous folks, too. Felder must make difficult choices about what to put in and what to leave out of his script and musical excerpts, and what emerges is what he feels is most important about his subject, and not necessarily a reflection of what that person may have chosen to discuss if he had an hour and 45 minutes to tell us about himself.

In Maestro, we are left with several key points about Leonard Bernstein, all laid clearly but subtly before us. This modulated narrative is perhaps the greatest achievement of Maestro, emotional realities are slipped in, not stated. We find Bernstein as the worshipful mentee, a major world figure, a collaborator with seminal musical figures (Jerome Robbins, Stephen Sondheim, etc.), a father, lover, and ultimately, a man with a respectable acceptance of his own life and work. All in all, a very special night in the theater.

top of page

MAESTRO: THE ART OF LEONARD BERNSTEIN

music by LEONARD BERNSTEIN

book by HERSHEY FELDER

directed by JOEL ZWICK

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

November 2-December 12, 2010

(Opened 11/10, Rev’d 11/23)

CAST Hershey Felder

PRODUCTION Francois-Pierre Coutour, set/lights/projections; Andrew Wilder, production design; Erik Carstensen, sound; GiGi Garcia, stage management