JULY 2006

Click title to jump to review

AND THE WINNER IS by Mitch Albom | Laguna Playhouse

CHRISTMAS ON MARS by Harry Kondoleon | The Old Globe

GOD OF HELL by Sam Shepard | Geffen Playhouse

LITTLE EGYPT by Lynn Siefert and Geoff Henry | Matrix Theatre

MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN by Bertolt Brecht | La Jolla Playhouse

SLOW DANCE ON THE KILLING GROUND by William Hanley | Athena Theatre / The Lounge

TICK, TICK . . . BOOM by Jonathan Larsen | The Coronet

THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE by William Saroyan | The Open Fist

WITHOUT WALLS by Richard Greenberg | Mark Taper Forum

O

Taking 'Courage

O

Bertolt Brecht intentionally wrote Mother Courage to keep audiences detached, the better to see it for the point it had to make – war is costly, vulgar, and ultimately inexcusable for any people who dare consider themselves civilized. This creates conflicting demands on productions. Where to distance the viewer and where to connect?

To solve that conundrum, an English-speaking theater looks to its adaptation, director and design team. By bringing together David Hare’s adaptation with new music by Gina Leishman under the guidance of Lisa Peterson and her team, the La Jolla Playhouse production in the Mandell Weiss Forum through July 23, feels like the production Brecht would want for a Southern California audience. It flows with the power while remaining unselfconsciousness.

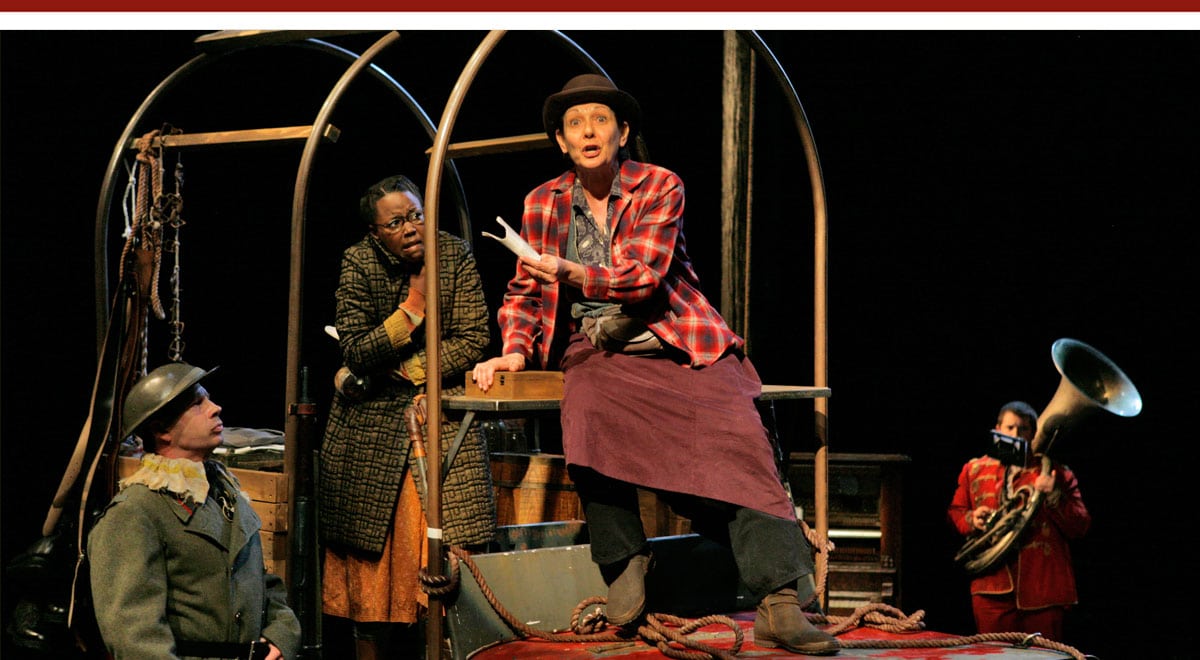

Director Peterson and set designer Rachel Hauck have turned the Forum stage area into one vast blackboard-paneled squash court, which beautifully offsets the faded color of David Zinn’s distressed costumes. It also brings the Brecht/Hare language to the forefront as the actors chalk key words and descriptions onto the floor and the walls. With a couple of striped, full-width drapes to close off playing areas, the versatile cast lead by Yvonne Coll as Courage, scuff the accumulating words to powdery memory. Peterson's concept capably delivers a war story of people destroyed by their own adherence to the war's myths.

"Mother Courage" is the adopted name of Anna Fielding, who is traveling with three children by different fathers during the Thirty Years’ War in the first half of the 1600s. They are bold Eilif (Scott Drummond), the dim-witted Swiss Cheese (Ryan Shams) and the mute Kattrin (Hilary Ward). Their home and business is an old jeep missing its engine and two front tires that has been fashioned into a kind of gypsy wagon with a tongue by which the male children pull it. The family survives by selling leftover war goods to those people left destitute by the fighting. On their travels they meet various soldiers, clerics, government officials and friends. All are lost and none will be redeemed. The story plods along at the pace of Anna's jeep, her children being lost to the battles as she goes.

She pays a high cost for nothing more than insufferable survival.

Leishman’s score is a rich fabric of drinking songs, burlesque numbers and sad ballads, while Coll carries the show, always careful not to over-engage. Her Puerto Rican accent gives the play a nice Western Hemisphere relevance. Also shining in their performances are Patrick Kerr and Katie Barrett in multiple roles.

top of page

MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN

by BERTOLT BRECHT

adapted by DAVID HARE

music by GINA LEISHMAN

directed by LISA PETERSON

LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE

June 20-July 23, 2006

CAST Katie Barret, Ivonne Coll, Mark Danisovszky, Scott Drummond, James Eckhouse, Brent Hinkley, Brian

Hostenske, Marc Damon Johnson, Patrick Kerr, Jonathan Piper, Ryan Shams, Hilary Ward

PRODUCTION Rachel Hauck, set; David Zinn, costumes; Marcus Dilliard, lights; Jill BC DuBoff, sound; Steve Rankin, fights

Patrick Kerr, Hilary Ward, and Ivonne Coll

Manuel Rotenberg

O

Street wise

O

The Athena Theatre has invested its modest resources in mounting a production of little-known William Hanley's 40-year-old 'Slow Dance on the Killing Ground' – a serious contender for the Dreariest Title title currently held by Lynn Nottage’s 'Crumbs from the Table of Joy.' Obviously not a play selection calculated to pack the tiny Lounge Theatre with easy marks.

Yet, last Saturday night they nearly filled the house with people who had at least 'Placed' in the pre-show free-style parking competition and who, without so much as an unwrapped lozenge, whispered epiphany or evicted throat-frog to break the spell, watched Hanley’s talky, near motionless play become a taut masquerade for three actors: One step Back, two steps forward; one step to deceive, two steps to come clean.

Slow Dance on the Killing Ground, which continues through July 29 at the Lounge (corner Santa Monica and El Centro), was introduced on Broadway in 1964. The play takes place on June 1, 1962, a day New York City countertops were cluttered with front page stories about the previous day’s execution of Adolph Eichmann. In 1960 the Israeli Mossad had captured the high-ranking Nazi in Argentina and taken him home to answer for his part in Germany’s extermination of millions. Hanley – with graceful insights from director Mark Thomas Boergers – uses that event as backdrop without making this a Holocaust play. He dances his characters just close enough to that abyss to bring out the darkness in their Personal histories. By the end, the play leaves us with a sense that justice and retribution are forces of nature that cannot be escaped, but with which we must somehow reconcile ourselves.

Hanley’s three characters are strangers meeting by accident in a small New York shop owned by a middle-aged German immigrant named Glas (Charles Howerton). The story unfolds in real time, so the length of the play (minus an intermission) encompasses everything that happens in the two hours they spend together. Randall (Matthew Thompson) is the young man who initiates things by cannonballing into the shop as if he’s the star of a fox hunt. He quickly smooths himself down and engages the half-empty Glas in an oblique game of cat-and-mouse, first proving his intellectual superiority, then his upper hand for violence, and finally his moral advantage.

Sometime later a young woman named Rosie (Veronique Ory) slips in, bearing the scrap of misread directions that should have had her at her abortion appointment hours earlier. Each character has enough secret showing to give the others something to pull on, with plenty left hidden to unravel as the evening unfolds.

This little microcosm that Hanley has devised allows him to touch on a number of tough subjects. Each topic – racism, anti-Semitism, the holocaust, teen pregnancy/abortion, matricide, prostitution, corrections facilities and the justice system – are given extra spin by each character's involvement in, denial of, or intolerance of them.

The men are better at masking their personal crimes and weaving the cover stories that protect them. Rosie is more candid and open. She is the one still able to avoid that dance along the black hole of guilt. All, however, prefer to see someone else come clean than to air his or her secrets. The gradual cycle of revelations and threats are played like a precise card game in which each player trumps the previous one. The evening ends when the final revelation proves the high card and that player is out. The discussion constantly sparks questions: Who has the right to judge another? Are the Israelis more justified in executing Eichmann than an abused child is of killing the perpetrating parent? Is abortion murder? How guilty is someone who is a passive participant in a crime? One character asks another if he would be 'willing to die to save my life?’ It’s a question that never leaves the stage, but moves from an absurd notion to one that bears thought to one that might in fact be the answer to the whole mess.

Howerton wears his role of Glas as comfortably as he does his shopkeeper’s apron. There is, in fact, a worn quality to Glas. Howerton waits for his moments, always preferring – as Glas would – to just blend into his shop. It’s a wonderfully natural performance. As Randall, Thompson has the play’s flashiest role. Despite being a young man, he is closest to the end of his life. Perhaps that’s why he packs so much into every speech. Purported to have an IQ above 180, Randall delights in showing off his vocabulary and his perspicacity, but can’t stop from displaying a hair-trigger temper. It makes for an extremely dense and varied line-load as he shifts in and out of black street patois -- his disguise. It’s a showcase role that Thompson makes look easy. Whether showing off his overwrought language or trying to disguise it behind in your face jangle-jive, he's constantly firing on multi-syllable cylinders. When ‘Mod Squad's’ Clarence Williams III created the role he was recognized with a Tony nomination and a Theater World Award. The role comes with a danger, however, as it begs an actor to go overboard. It's a line Thompson is clearly aware but needs always to watch. As Rosie, Ory has the least stage time and, as mentioned, the least darkness to conceal. Still, she works her part as foil for the other two very well, blending the right amounts of naïvete, commitment and indignation.

The lighting design is lovely. The opening cross fade as the upstage scrim opaques out the dancers to reveal Glas on his ladder is a beautifully rendered bit of transportation. However, at least three times the lights cut to just stage right to isolate an actor. Unfortunately, the actor was at best half in the light. If it can't be coordinated, just leave the whole place lighted. As mentioned, however, the designer’s use of the scrim storefront window to show the dancers worked well. Unfortunately, the dancing, while nice at first, did not carry the tension that the actors were creating. Especially when a dancer can be seen just walking offstage before the scrim fills in. At this performance, the final tableau missed the timing needed for the ’A-Ha’ moment, which was unfortunate given the actors' performances.

Still, Boergers’ work with this cast gives Hanley’s surprisingly interesting script a good spin, and turns this theater cum lounge into a welcome place for strangers to meet for an evening of probing conversation and an added dimension to the idea of a play performed in real time.

top of page

SLOW DANCE ON THE KILLING GROUND

by WILLIAM HANLEY

directed by MARK THOMAS BOERGERS

ATHENA THEATRE

June 22-July 29, 2006

at the Lounge Theatre

CAST Charles Howerton, Veronique Ory, Matthew Thompson DANCERS Kim Parmon, Adrian Vatsky

PRODUCTION Stefan Depner, set; Adam Voigts, costumes; Johnny Ryman, lights; John Bobek, sound;

Kim Parmon, choreography

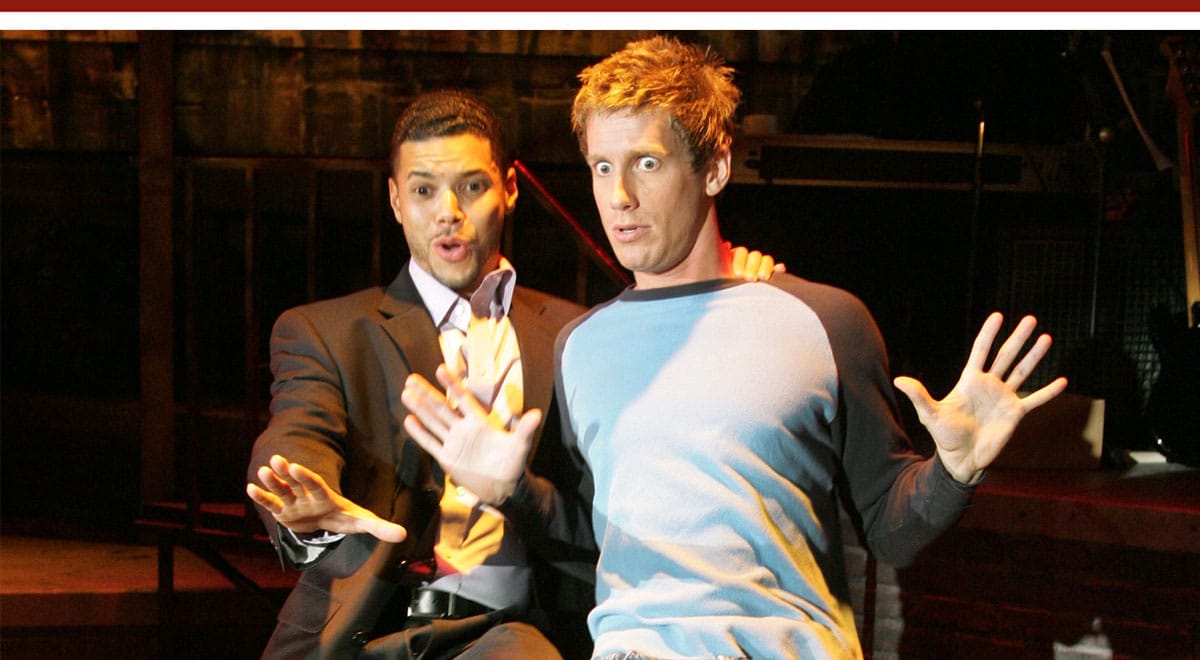

Matthew Thompson, Charles Howerton and Veronique Ory, with Kim Parmon and Adrian Vatsky in background

Manuel Rotenberg

PRODUCTION

O

Larson-y

O

That the landmark ‘Rent’ was Jonathan Larson’s first musical to get a proper production is the stuff of theater legend. That he died the night before its first audience is mythic. ‘Rent’ went on to eclipse ‘Hair’ as proof that the best rock musicals can be as socially significant as the best rock music. Larson’s death at 35 makes anything he did before ‘Rent’ of great interest.

In 1983, he started a musical based on Orwell’s ‘1984,’ changing the name to ‘Superbia’ when Orwell’s estate refused him permission to use the name and story. ‘Superbia’ had its champions, but could not get a production that made any noise. Larson funneled his growing frustration over thethankless career he’d chosen into a solo show called ‘Boho Days.’ In ‘Boho Days,’ he played all the parts of friends and industry types, backed by his own piano playing and a small band. The show, expanded to three actors several years ago under the fatalistic new title ‘tick, tick . . . BOOM!’ is now at L.A.’s Coronet through July.

The addition of two voices add depth to the vocalizing and helps embody the principal other characters in the narrator’s life. The story involves Jonathan (Andrew Samonsky), a piano playing composer who is resisting the pull of a girlfriend (Tami Tappan Damiano, but played by Robin De Lano at this performance) to move away from New York, and a friend (Wilson Cruz) to move into a marketing job to help pay his bills. The story takes place around Jonathan’s 30th birthday. The ticking of the title is his sense that he needs to accomplish something soon or he may never. The aura of doom is here, but in the character of his friend, Mike, who reveals that he is terminally ill.

No doubt ‘tick, Tick . . . BOOM!’ was more impressive as a one-man show with piano. Then it would have been much more than meets the eyes. Then, Larson hopping back and forth between characters would have been entertainment enough, and glossed over the tired story of artist trying to make it without selling out to the dreaded world of marketing and expensive clothes and cars. Also, in more of a revue structure, the songs would have better breathed on their own and not been expected to move the story and so on.

The brightest spot here is the work of director Scott Schwartz, who keeps things moving and imaginative. He pushes the staging almost to the point of being too obtrusive, but it is welcome flourish and much needed. The performers are all fine, with special kudos to De Lano for stepping in without missing a beat.

What Larson had – and it still shines through here – is a love of theater and musicals and contemporary music. His melodies and rhythms seem to flow easily and his lyrics, while not in the league as his idol, Stephen Sondheim, nevertheless reveal a sensibility for what is best about this musical form. In fact, it’s his ‘Sunday,’ a tribute-parody of the opening number of the master’s ‘Sunday in the Park with George,’ which affords the one real great moment.

While this show is not the stuff of legend, as an average show by a mythic character, it’s worth the visit.

top of page

TICK TICK…BOOM!

book, music and lyrics by JONATHAN LARSON

script supervision by DAVID AUBURN

vocal arrangements and orchestrations by STEPHEN OREMUS

directed by SCOTT SCHWARTZ

CORONET THEATRE

through July 16, 2006

CAST Wilson Cruz, Andrew Samonsky, Tami Tappan Damiano. Understudies: Robin De Lano (reviewed)

and Matt Lutz. Band: Brent Crayon, Dave Wood, Oliver Steinberg, Greg Inverso

PRODUCTION David Farley, sets and costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; Drew Dalzell, sound

Wilson Cruz, Andrew Samonsky

O

Human dramedy

O

‘The Time of Your Life,’ William Saroyan’s eerie barroom drama, is a confounding piece of theater. Despite being written in a matter of weeks, and being internally stamped with the date of its October 1939 Broadway debut, it has retained a timelessness that still appeals to theater companies and their audiences. It is populated by dozens of vivid characters, but has a pervasive loneliness, with only two or three people speaking to each other at a time. One suspects Saroyan doesn't really want these characters to be individual voices. He prefers them as a Depression-era choir singing the praises of American opportunity, even though the ringing in the ears as we exit is of opportunities missedand squandered – if they materialized at all. And, as a final irony, the play was dismissed by early critics as too optimistic despite ending with a murder that, with the playwright’s blessing, will go unpunished.

These conflicting qualities of ineffability and reality must co-exist as equals, and this creates a huge challenge for any company. The play was nearly abandoned in its New Haven previews when director Bobby Lewis – who had found the essence of Saroyan's previous effort – went too far into the fanciful and forsook the grit. It took the author and the lead actor – Eddie Dowling – to take the reins and get it back on track. They were successful enough to earn the 1940 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, which, after all that, Saroyan refused to accept.

The play’s theatricality and large-cast requirement have proven irresistible for companies who, moving up from a confining space to a larger one want some feather-fluffing to accompany the cockcrow of their new day. South Coast Repertory did it, not once but twice – when moving into their Third and again Fourth Step Theatres in 1967 and 1978 respectively. Now, the Open Fist Theater Company has mounted a sincere staging under the direction of Stefan Novinski (assisted by Amanda Weier), to herald their new home on Santa Monica – the old Actor’s Gang space.

The Open Fist production, through July 1, certainly affords a good opportunity to experience the play and allows the genius to be revealed. It brims with the kind of energy that growing companies, still bound by devotion to the art and each other, have in abundance. And this production also features two notable performances amid a company that gets the job done adequately. Novinski and his designers have given the physical space a sense of dusty authenticity, although the costumes feel a bit off-the-rack. (It’s embarrassing when the on-stage drunk has a better crease in his pants that the reviewer.)

Because the play is not a straight narrative, Saroyan hasn’t given actors much to hang their hats on. It’s a test to see what actors can conjure up out of nothing. Among the most successful are Michael Patrick McGill as Nick, Mark Thomsen as Dudley and Rob Nagle as McCarthy. Many characters have nothing to do and must occupy themselves sitting and staring so as not to pull focus as they sit for hours awaiting their lines of dialogue. (Case in point, Willie [Jeremy Johnson] has his moment late in the story and, after

occupying space as carefully as a potted plant, erupts into a character bursting with personality. We know this kind of guy, in a real bar, would have been into everybody’s business all night long. But here he must keep quite. A necessity that provides an unintentional strangeness.)

The lead role of Joe, around whom the action swirls, is a tall order, and Michael Franco gives it a good shot. Still, the kind of irrepressible Irish charisma probably imagined by Saroyan and delivered by Dowling, is missing. Franco’s Joe is just another guy in the bar, albeit a guy with deep pockets. He’s the principal conundrum in a stage full of them, living by his wits without seeming to use them: mystified and mysterious. He has the strange duality of successfully playing fate's odds while appearing to be their victim. He is a fan of people who says they’re “all wonderful,” yet someone who for years has treated the person closest to him like a servant.

Two performances rise above the mix. As Kit Carson, a bizarre throwback to Western myth, alcoholism, or both, Bruce A. Dickinson seems to have wandered in off a desert. There’s a too-much-sun intensity to both his storytelling and his story-listening. It’s a key role, and depending on how a production goes, it’s potentially more important than Joe. It is Carson who if not dismissed as a lunatic, opens doors to questions about life, time and the world these characters occupy. He’s the only one obsessed with time, making a big point about his age, 58, and his expectation to be dead before he reaches 60. Yet, in one of his numerous date-filled rambles, he reveals that he may be 70 years old – or, perhaps, no longer living. What’s more, in the speech that ends the play, he drifts off into a recollection of what he has just done, marking it as a vague memory of something “In 1939, I think it was. October,” the month the play opened on Broadway.

The other stand-out is Hannah Dalton as Mary L. This is the performance that takes the show out of the building and reveals what the play is really all about. Mary is a sad beauty who is resolved to her life. Right there you have potency that the real artists can find. In her brief exchange with Joe we get to see the whole picture: the opportunities lost, grabbed, remaining and destined to be forever ignored. It’s the kind of performing you can’t teach. In those few moments, Dalton gives her scene the weight that can

plumb those murky waters of what might have been. And Franco goes along for some of his best work. It is a poignant moment that, in a way, underscores Saroyan’s point that our time may be brief, but we need to make the most of it.

It’s worth noting that the 1938 Pulitzer Prize had gone to Thorton Wilder’s “Our Town,” in which one character experiences time from the vantage of those who no longer live in it. Carson’s insistence on erroneous life spans may in fact serve that same purpose. Because, if they were ever there to begin with, the characters in Saroyan’s Pacific Saloon would soon be gone. For those of us in 2006, they are. It’s Saroyan's timely reminder like the one from that grassy knoll above Grover’s Corners. “In the time of your life, live – so that in that good time there shall be no ugliness or death for yourself or for any life your life touches.”

top of page

THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE

by WILLIAM SAROYAN

directed by STEPHEN NOVINSKI

OPEN FIST THEATRE

CAST Weston Blakesley, Amelia Borella, Benjamin Burdick, Alexander Burke, Melanie Chapman, Jacque Lynn Colton, Hannah Dalton, Bruce A. Dickinson, Heather Fox, Michael Franco, Jeff Graham, Sara Jones, Anna Khaja, Jimmy Kieffer, Subash Kundanmal, Michael Patrick McGill, Rob Nagle, Ibrahim Saba, Andrew Schlessinger, Mark Thomsen, Peter Vance

PRODUCTION Thomas Lynch/Charlie Corcoran, set; David C. Woolard, costumes; Donald Holder, lights; Mark Bennett, sound

Anna Khaja and Michael Franco

Maia Rostenfeld

O

Don't stand so …

O

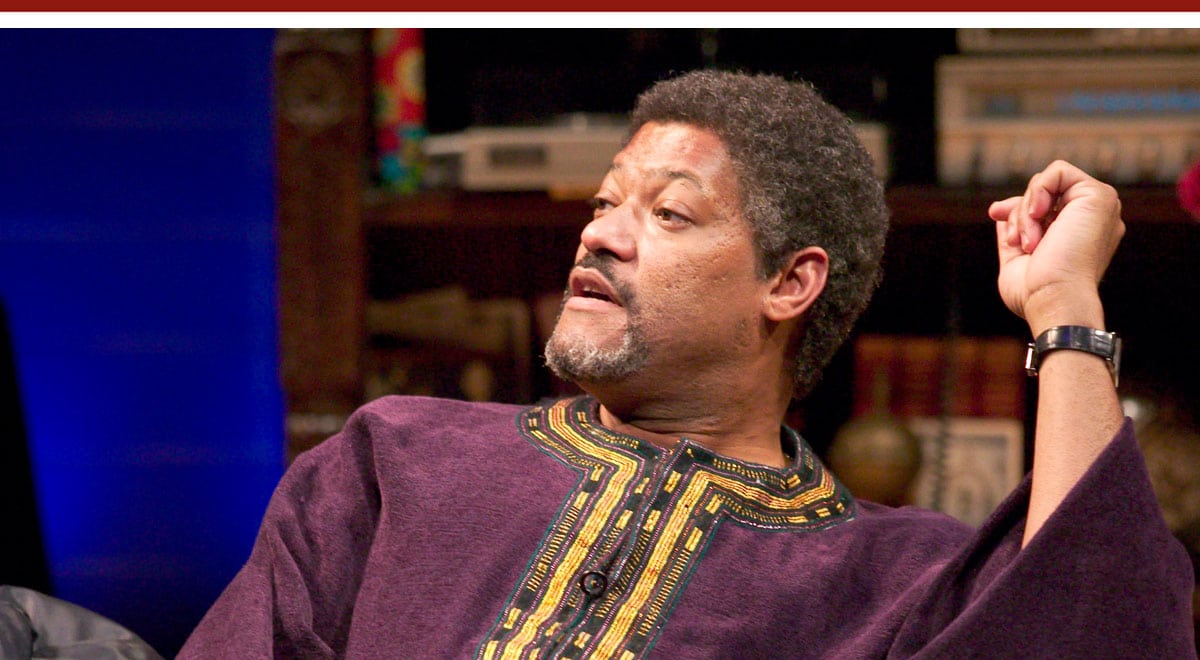

Morocco Hemphill, the high school drama teacher at the center of Alfred Uhry’s ‘Without Walls’ (in its West Coast premiere at the Mark Taper Forum through July 16), explains to one of the students who fill out the three-character story, that he knows when someone has talent.

Morocco (Laurence Fishburne) tells Anton (Matt Lanter) that he deserves the break, because he is gifted; Lexy (Amanda MacDonald), the school’s self-disciplined star, “has gone as far as she’s going to go.” This explains why the instructor has invested so much of his personal and political capital in the young man who lies, cheats and manipulates people. Ultimately Anton will cost Morocco his job and–sadder –deprive future students of an inspiring mentor. All this pain and suffering might be worth the cost, and Uhry's script might make more sense, if we saw in Anton what Morocco sees.

Unfortunately, although Mr. Fishburne’s vivid and heartfelt Morocco confirms that the film star has the gift for live theater, Mr. Lanter gives us an Anton who is not much deeper than the words on the script. And, this time out, Mr. Uhry's words don't feel very deep.

Mr. Uhry wrote ‘Driving Miss Daisy’ and ‘Last Night at Ballyhoo,’ winning Tonys for both and the Pulitzer Prize for ‘Daisy.’ Those stories of personal awakening were set against backdrops of racism and (intra-Semitic) anti-Semitism. Here, however, the backdrop, while hinted at, isn’t clear. It’s 1975, six years after after Gay Liberation’s big bang at Stonewall, but still a long way from the openness about on the subject we have today. Bachelor Morocco has the theatrical gestures and precise diction to set him up as a discreet closet case. But that is never made manifest by the playwright, which draws the audience into a cagey kind of complicit stereotyping that helps with the play's clumsy climax. ‘Without Walls’ is how the Dewey School’s describes its teaching philosophy. But its assertions of unfettered freedom are camera-ready only and the administration is on course to buckle at the first hint of improper unbuckling, ready only and the administration is on course to buckle at the first hint of improper unbuckling. discreet closet case. But that is never made manifest by the playwright, which draws the audience into a cagey kind of complicit stereotyping that helps with the play's clumsy climax.

Fishburne inhabits Morocco comfortably. The teacher so cares for his kids that he effortlessly mixes tough love and tolerance to keep them on task. Despite the potential dangers – and recalling a less-suspicious era – he is willing to use his home as rehearsal space or shelter – as long as students clear it with parents. When alone, he is the picture of self-content. His 1970s look recalls a svelte Rosie Grier, especially under the drape of his purple kaftan. He happily occupies himself with cooking and jazz, employing herb to the advantage of both. Into this settled, nurturing environment drops Anton, an emotionally crippled survivor of his own wreckage who is utterly unreliable, saying whatever is necessary to manipulate those around him. Here, Uhry has backed himself into a corner. We have no idea what about Anton is real, no idea of what he needs or what motivates him. It's all going to depend on a gifted actor to get this sketchy character in order to make this play special. A purported visit between his mother and Morocco doesn’t clear much up. It’s hard to empathize with the troubled youth who, in being helped to break through the debris heaped upon him by childhood trauma, inflicts more pain on those around him: 'firing on the rescuers,' so to speak. As Lizy, the other life Anton ruins, MacDonald delivers the required range in the role with the least demands.

Uhry wants this to be an ode to the teacher student relationship, but it needs to first be more respectful of the writer’s relationship to his play. Uhry’s voice is not that of a poet. He’s a storyteller. His dialogue merely gets us from point A to B. And when the ride from A to B feels as bumpy as this one does, there’s a problem. Certainly a more nuanced performance in the role of Anton would have revealed something more. There are glimpses of a subject that could provide a great play. Unfortunately, the only thing great about this adventure is Mr. Fishburne. However, given the fact that the house was filled with people who clearly came to see him, that may be enough for now. Hopefully, there'll be another time and another script and another actor who can really stand up to him. Then the distinction between those who have the gift and those who merely work, won't be played out before our eyes.

WITHOUT WALLS

by ALFRED UHRY

directed by CHRISTOPHER ASHLEY

MARK TAPER FORUM

through July 16, 2006

CAST Lawrence Fishburne, Matt Lanter, Amanda MacDonald

PRODUCTION Thomas Lynch/Charlie Corcoran, set; David C. Woolard, costumes; Donald Holder, lights; Mark Bennett, sound