JULY 2010

Click title to jump to review

THE CLEAN HOUSE by Sarah Ruhl | Odyssey Theatre Ensemble/Circle X

THE GOOD BOOK OF PEDANTRY AND WONDER by Stephen D. Giurgis | Theatre @ Boston Court

THE LION IN WINTER by James Goldman | Shakespeare Santa Cruz

LOVE'S LABOR'S LOST by William Shakespeare | Shakespeare Santa Cruz

Comic cleanser

In The Clean House, her break-out play from 2006, Sarah Ruhl mentions the soul-cleansing power of prayer, the purging properties of comedy, and the calming effect of a freshly scrubbed home. But the cleaning solution at the heart of this entertaining if uneven play, continuing at the Odyssey Theatre through August 1, is love – unrestrained, inexplicable and, in the best of times, very messy.

However, the play seems a bit messy in Stephen Kruck's staging. Some dulling of the impact comes from a dual-lead structure in which neither principle character drives the play, but instead has the play happen to them. Or, it may come from trying to balance farcical elements that border on magical realism with painful truths that, without context, border on melodrama.

Opening and closing the play is Matilje, only child of two Brazilians who were heart-stoppingly funny. In the family tradition, Matilje has been practicing her delivery, and formulating new jokes (one, told in Portuguese opens the show). While waiting for her show business break and trying to craft the funniest joke ever, she cleans the house of Lane (Colette Kilroy) and Charles (John Walcutt, replacing Don Fischer for the extension), successful doctors at an "important hospital." There is much to love about Matilje, especially in this centered portrait by Zilah Mendoza (the actress who originated the role in Bill Rauch’s 2006 premiere, taking over for Elizabeth Liang during the extension).

Lane is the other half of the play’s center. By play’s end she will come to greater awareness about the revitalizing properties of true, unselfish love. However, she will be dragged to this minor epiphany by the actions of her husband – who leaves her for Ana (Denise Blasor). Argentinan Ana is a cancer patient of Charles' whom he recognizes as his "basherte," a Yiddish term for "destiny" commonly used to refer to one's perfect complement and "soulmate."

While a single Lane change seems hard to detect and (beyond the Kevorkianesque success of her killer joke) Matilje's gains are similarly slight, the play's arc falls to Charles. This may be due to Walcutt's performance, which is spot-on – equally tapping the hilarity and heartbreak in his life-altering affair.. He is able to stretch for the laugh without leaving the ground. Blasor, too, keeps things bubbling along, creating a character who calmly takes life, love and death in stride. (Blasor and Walcutt also appear in several zany pantomimes as Matilje’s parents.) These two are so much the heart that drives the play that the others become observers, including Virginia,. Lane’s unhappily married sister. Virginia (an appealing D.J. Harner) so loves to house-clean that she offers to become the distracted Matilje’s ghost-duster. Kilroy, one of the better stage actresses in Southern California, seems to have been directed to push hard for laughs, which further marginalizes the passive character's command of the story.

In general, perhaps tellingly, the two actors who weren’t around for the full rehearsals seem to be faring better. Nevertheless, this is one of the more successful plays of the past decade, with another production opening at Long Beach's International City Theatre in lae August. It's an important work to see, and, despite the missteps, Kilroy, Mendoza, Blasor, Harner and especially Walcutt are an excellent group to share it with.

top of page

THE CLEAN HOUSE

by SARAH RUHL

directed by STEVAN KRUCK

ODYSSEY THEATRE

May 13-July 18, 2010; extended to August 1

(Opened 5/13, Rev’d 7/23)

CAST Denise Blasor, Don Fisher, D.J. Harner, Colette Kilroy, Elizabeth Liang (Zilah Mendoza and John Walcutt replaced Liang and Fisher for extension.)

PRODUCTION Federica Nascimento, set/costumes; Kathi O’Donohue, lights; Sean Kozma, sound; Lisa Szolovits, asst. director; Rachel Manheimer, stage management

D.J. Harner and Colette Kilroy

Ron Sossi

Binding words

James Murray, the obsessive etymologist who drove himself, his children, and a phalanx of linguaphiles to create the encyclopedic Oxford English Dictionary (OED), is the inspiration of Moby Pomerance’s The Good Book of Pedantry and Wonder, premiering (through August 29) at the Theatre @ Boston Court in co-production with Circle X.

Pomerance avoids reliance on exposition and biographical detail to such a degree that the play does not clearly establish what it is these workers are doing. Knowing that would let us progress to what Pomerance wants us to focus on, his themes of how people fail to communicate (deliciously ironic in a room walled with words), how words both bind us and separate us, and how they bring the world into focus as they distance it, as well as less compelling issues of filial piety and family duty.

The play, set in Oxford in the mid-1880s, introduces Murray (John Getz), his daughter Jane (Melanie Lora), and a longtime helper named Smythic (Time Winters). Before Jane arrives for her day’s work, one volunteer announces he is quitting, which leaves Smythic alone to rehearse revealing his feelings to Jane. When she arrives he falls silent for the first statement of the dominant theme that will have variations over the two-and-a-quarter hour, two-act play.

The arrival of Jane’s older brother Paul (Ryan Welsh) after eight years traveling sets in motion confrontations and recollections between the siblings. Jane stayed to care for their aging father and help with his work while Paul went out to explore the world and pursue his passion – the equally precise cartography. He contends map-making is closer to reality because it "traces" the world rather than interpreting it as language does. That Murray doesn't notice – or acknowledge – Paul rings the neglectful parent bell, and opens another door through which Pomerance will take us to address the matter of being authentic and not hiding behind words.

In order to make Jane the long-suffering, dutiful daughter who needs her brother to relieve her so she can go off on her own, Pomerance distills the facts of Murray’s children. He and his second wife, Ada, had 11 children, all of whom worked at one time or another on creating the dictionary and none of whom would have been given as plain a name as Jane or Paul. After the eldest boy and girl received fairly common names of Harold and Hilda, the rest of the sons were Ethelbert, Wilifrid, Oswyn, Aelfric, and Jowett, and the daughters Ethelwyn, Elsie and Rosfrith (perhaps the two who served for the longest periods on the Dictionary staff) and Gwyneth. An opportunity lost to underscore that rich words permeated Murray's parenting as well as his profession.

In John Langs’ staging, performances further narrow the characters into singular modes. Lora, who showed her range in last year’s Collected Stories in Costa Mesa, here feels consigned to exchanges that are cool and tinged with sarcasm. Getz’ Murray seems less the passionate lover of language and more the flinty martinet who is so quick to anger as to obscure what was by all accounts a man of tremendous range. Winters, stuck with a character whose two functions are sorting definitions and carrying a torch for Jane, is limited to being put-out and bottled up. Welsh, the only one with a life outside the workroom, gets a richer personality to explore and does so nicely. Three other characters, played by Travis Michael Holder, Henry Todd Ostendorf and Gillian Doyle, have interesting exchanges with Murray or others in which Pomerance gets to explore his themes away from the father-child relationships. In these moments (especially Doyle's) the play shows its greatest promise.

Brian Sidney Bembridge’s award-worthy set becomes the most successful element of the production in balancing these realms of biography and metaphor. Unfortunately, its visual realism, and along with Dianne K. Graebner’s lovely period costumes, suggest that what we’re seeing is a realistic depiction.

Murray’s story has plenty of high-stakes drama and seems a shame to blur. At the time of his death in 1915, at the age of 78, Murray had devoted 35 years to the OED, which was still 13 years from publication. His original estimate of ten years to produce four volumes of 7,000 pages, was expanded by perfectionism to 50 years, 12 volumes, 414,825 words and 1,827,306 citations to illustrate their meanings. According to one report, in his first five years, when he thought he could work part-time, he got as far as the word "ant."

top of page

THE GOOD BOOK OF PEDANTRY AND WONDER

by MOBY POMERANCE

directed by JOHN LANGS

THEATRE @ BOSTON COURT / CIRCLE X

July 22-August 29, 2010

(Opened 7/31; rev’d 8/6)

CAST Gillian Doyle, John Getz, Travis Michael Holder, Melanie Lora, Henry Todd Ostendorf, Time Winters, Ryan Welsh; u/s – Bryan Bellomo, David Fruechting, Blake Griffin, Suzy Jane Hunt, Dale Sandlin, Doug Sutherland, Wendy Worthington

PRODUCTION Brian Sidney Bembridge, set/lights; Dianne K. Graebner, costumes; Bruno Louchouarn, music/sound; Tracy Winters, dialect; Katherine Haan, stage management

HISTORY Support from The Harold & Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust and the L. A. County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Workshopped at Geva Theater in Rochester, N.Y. World premiere.

Ryan Welsh and Melanie Lora

Ed Krieger

Clearing the heir

There’s nothing ascendant about ascension in James Goldman’s 1966 play about the family feud over who should succeed Henry II. However, Shakespeare Santa Cruz’s indoor staging of The Lion in Winter (through August), which marks Artistic Director Marco Barricelli’s stage debut at the company he's run since 2007, reveals the power and shrewdness of this historic character – and the man portraying him.

Henry II, great-grandson of William the Conquerer, was only 21 when, through military and political maneuvering, he became the first King of England in December 1154. (Previously the title had been"King of the English.") He had married Eleanor of Aquitane, also French-born, at 19, and she soon had William, the first of their eight children. William would die in infancy and the second, Henry, would live to lead a revolt against his father in 1173. He'd live to regret that bad idea, right up to his death, still out of his father's favor, ten years later. Eleanor, who encouraged her son's coup, was imprisoned for her part.

Goldman sets his play at Christmas 1183, six months after young Henry’s unhappy death – and as it will turn out, six years before the older Henry’s death. Though not historically accurate, Goldman makes the holiday the annual occasion for Henry to briefly relax Eleanor’s "house arrest" so she can be with her surviving sons – Richard, Geoffrey and John.

Henry never did free Eleanor (Richard would do that after asssuming the throne in 1189), and, creating the balance of tension for Goldman's robust script, Eleanor would never release her husband from his marriage vow. Goldman uses these two forms of containment to drive Lion. It's a rare case among English sovereigns where the old barstool bromide, "Can't live with her, can't kill her," actually applies. Henry loves her, with all his heart and mind – if not his body – for her powerful intelligence and fearlessness. Eleanor provides rich opportunity for an actress, and Barricelli and director Richard E.T. White have brought in Old Globe Associate Artist Kandis Chappell for the role. Together, she and Barricelli – who appeared as Elizabeth and Oxford in ACT's production of The Beard of Avon – well-tether this tug-of-wits, giving audiences an opportunity to see two of California’s best stage actors square off.

On this Christmas, Henry and Eleanor quickly fall into their ongoing debate over his choice of an heir. He has indicated that it will be the eldest, Richard (John Pasha), by long ago picking him to wed Alais (Mairin Lee), the sister of France’s future King, Phillip (Adam Yazbeck). She has been living in the castle since childhood as Richard's intended. Phillip, visiting for the holidays, is pressing for the wedding to take place soon, so as to secure the countries' alliance (and lock down the gift of land he's to get in the bargain). The audience has already seen in the opening scene, however, that Henry has taken his beautiful ward for his mistress.

Because Eleanor steadfastly refuses to agree to an annulment, another dimension of tension is added to their relationship. She further encourages Geoffrey (Aaron Blakely) and John (Dylan Saunders) to unseat their father.

The complications of the relationships – which are far more intricate than even Goldman can show – are enough to spin the head, and in the first act, there is some grinding of gears as the plots jostle along. White’s staging, which occasionally employs some ostentatious blocking, can only do so much to keep the machinaations running smoothly. Still, this is a solid supporting cast that keeps the energy and insights strong, especially Ms. Lee, who holds her own with the two veterans. Saunders and Blakelyare enjoyable, creating a chemistry in the manner of Stoppard's Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern.

Come Act II, with the exposition mostly behind us, the stage is effectively handed over to Barricelli, Chappell and Lee and their triangle becomes more entangled in their individual webs tighten. Goldman managed to mine this big-canvas historic drama for detailed human portraits. Though he called it a “comedy,” and the original cast starred The Music Man's Robert Preston, we now see it as high-intensity drama. And, to that end,White, Barricelli and Chappell have created the kind of explosive face-off that Goldman may not have imagined, but certainly provided for.

top of page

THE LION IN WINTER

by JAMES GOLDMAN

directed by RICHARD E.T. WHITE

SHAKESPEARE SANTA CRUZ

July-August 2010

(Opened 7/23, rev'd 7/25)

CAST Marco Barricelli, Aaron Blakely, Kandis Chappell, Mairin Lee, John Pasha, Dylan Saunders, Adam Yazbeck

PRODUCTION John Iacovelli, set; B. Modern, costumes; Kent Dorsey, lights; Bonfire Madigan Shive, music; Gregory Scharpen, sound; Jakey Hicks/Jessica Carter, wigs/hair; Lori Amondson, stage management

HISTORY Premiered at the Ambassador Theatre on March 3, 1966, with Robert Preston and Rosemary Harris (who won a Tony Award).

Marco Barricelli and Kandis Chappell

rr jones

Getting 'Lost' in the woods

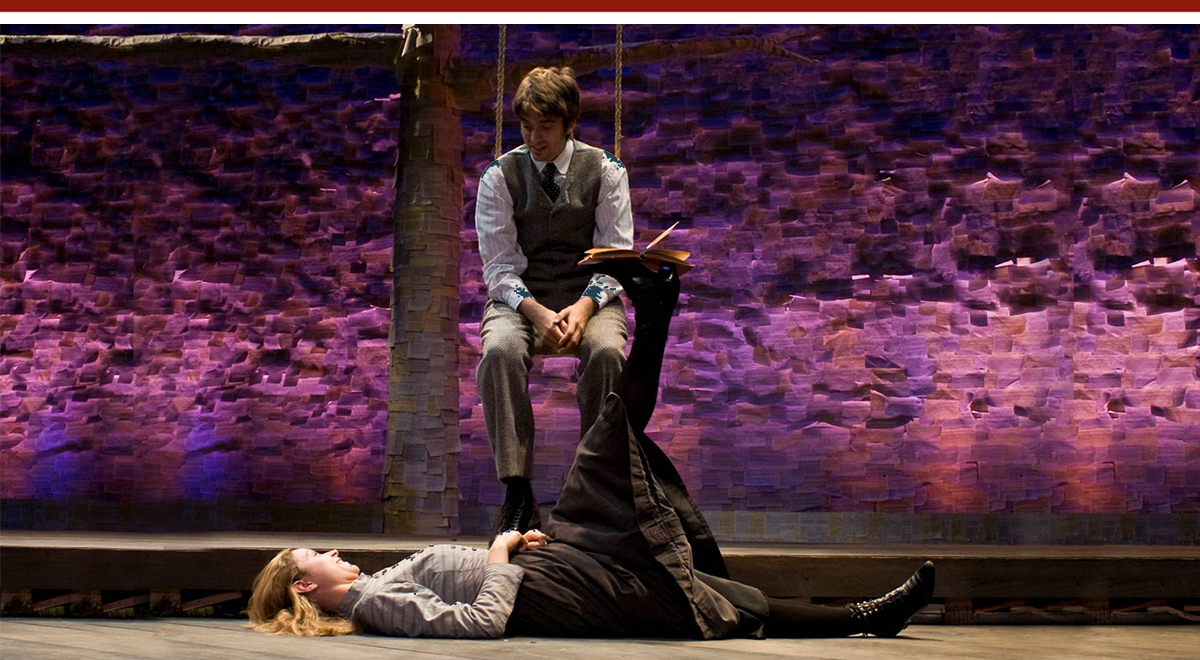

Love’s Labor’s Lost is one of Shakespeare’s lesser works. Though less produced, it still has a prominent place in the playwright’s progress. In 1598, it became the first published script to bear Shakespeare’s name. This summer (through August 29), in Scott Wentworth’s spirited staging, it finds its place in the outdoor amphitheater of Shakespeare Santa Cruz, where, into the dark rise of redwoods, its "word-music" floats and crackles like bonfire sparks.

Written in the mid-1590s when he was clearly still amazed by his facility with language, Love’s Labor’s Lost lost some heft when Shakespeare the wordsmith overpowered Shakespeare the playwright. In love with the sound of his own "word-music" as Shaw called it, he chose words for their cadence, consonance and lyricism at the expense of meaning and character or plot development. While this is indispensable to what makes Shakespeare great, here it grows unruly: The flowers have obscured the path. A draught imprudently drawn reads not half-full, or half-gone, but o’er poured with impotent froth.

It begins with the usual promise of dual rewards – both in sound and substance. Ferdinand, King of Navarre (V. Craig Heidenreich), and three of his lords have sworn to cloister themselves in pursuit of knowledge for a full 12 months. They will do without comfort and forgo female company. As quickly as the lords – Berowne (Adam O’Byrne), Longaville (Brett Duggan), and Dumaine (Richard Prioleau) – sign the pact, they remember that the Princess of France (Marion Adler) and three attendants are due to arrive within hours. Ferdinand admits it will be embarrassing, but their year’s contract is too important to be abandoned before its ink has dried. He will erect tents for the women to be housed outside the castle gate.

The premise poses a worthwhile question. Can (and should) man’s aspirations to "developing the mind" withstand the pullback of love and loin? No sooner has Shakespeare staked his grounds for inquiry than he has lost interest, and as if to answer the question by dramaturgy, goes romping off into the bush. With the commitment to individual development abandoned, and the inner tension between heart and head relaxed, the play becomes a mere merry-go-round for skirt chasing.

Outdoors, however, with this inviting physical production by Michael Cazio (set), Brandin Barón (costumes), Peter West (lights), and Rodolgo Ortega (music/sound), we begin the play halfway into one of Shakespeare’s magical forests. The lively company, united and inspired by Wentworth’s imaginative vision, easily draws us in the rest of the way.

In his preface to a 1927 printing of the play, Harley Granville-Barker wrote that “if the music is clear and fine, as Elizabethan music was, if the costumes strike their note of fantastic beauty, if, above all, the speech and movements of the actors are fine and rhythmical too, then this quaint medley of mask and play can still be made delightful. But it asks for style in the acting. The whole play, first and last, demands style."

Wentworth mitigates elements in the text that were of relevance only to audiences at the time of its writing, by adding touches relevant to us, notably J. Todd Adams’ take on the rustic fool Costard, here channeling Sean Penn’s surfer dude from Ridgemont High. In Moth's English boarding school outfit, Emily Krakowsky appears to be truant from Hogwarts. And, in a brief appearance measured by the second hand, Cooper Sivara's Forester beams a moonface-smile straight from Andy Kaufman’s Latka. (Though, that may not have been intended.)

The ladies – Dana Green as Rosaline, Alexandra Trow as Katherine, and Sherill Turner as Maria – are lovely and lively enough to distract any men from their "betterment." Victor Talmadge is the Spanish Don Armado, here an out-of-touch Prussian, or Russian, officer. And, Shoshona Brooks is the seductively earthy Jaquenetta.

Samuel Johnson wrote that, in Love's Labor's Lost "There are many passages mean, childish, and vulgar. But there are scattered through the whole many sparks of genius." [And, no play] has more evident marks of the hand of Shakespeare." Whether or not Shakespeare mishandled his play's potential, Wentworth and company have fully realized theirs.

top of page

LOVE’S LABOR’S LOST

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by SCOTT WENTWORTH

SHAKESPEARE SANTA CRUZ

July-August 2010

(Opened, Rev’d 7/24)

CAST J. Todd Adams, Marion Adler, Noah Averbach-Katz, Shashona Brooks, Brett Duggan, Dana Green, V. Craig Heidenreich, Corey Jones, Emily Krakowski, Jeff Mills, Joel Morello, Adam O’Byrne, Richard Prioleau, Mike Ryan, Cooper Sivara, Victor Talmadge, Alexandra Trow, Sherill TurnerPRODUCTION Michael Ganio, set; Brandin Baron, costumes; Peter West, lights; Stephen Buescher, choreographer; Rodolfo Ortega, music/sound; Jakey Hicks/Jessica Carter, wigs/hair; Michael Warren, dramaturg; Lori Amondson, stage management