MAY 2006

Click title to jump to review

ALL MY SONS by Arthur Miller | Geffen Playhouse

ARMS AND THE MAN by George Bernard Shaw | A Noise Within

BLUE DOOR by Tanya Barfield | South Coast Repertory

LAST EASTER by Byrony Lavery | Laguna Playhouse

THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare | A Noise Within

TRYING by Joanna McClelland Glass | The Old Globe

Heir disaster

After winning a war against evil, Americans in 1947 felt themselves at the beginning of a glorious new era. America had staked its claim to political and economic righteousness. But Arthur Miller saw dangerous cracks in the engine that was accelerating America's emergence. That year his All My Sons introduced a family that embodied the underlying problem. The Geffen Playhouse has mounted a revival, through May 21, directed by Artistic Director Randall Arney, that offers a great look back into both theatrical and national history while providing one unforgettable performance.

All My Sons weaves together several plots of mythic proportions: greed masked as altruism, love submerged in self-pity and family ties built on lies. The Kellers have paid dearly for America's victory. It's been three-and-a-half years since their older son, a pilot, was reported missing. Now the surviving parents and brother need to move on. The seeds of their undoing, however, were sown years earlier. And, as they try to start fresh, they also must continue to cover those mistakes in layer upon layer of denial. Eventually, undermined by the lies, their world, symbolized by the beautiful color-of-money back lawn upon which the play is set, will cave in.

Patriarch Joe Keller (Len Cariou) is Miller's first great cautionary character written to warn a nation increasingly focused on commerce. Joe is a victim of the success-at-all-costs ethos. But unlike Willy Loman, the central victim of Miller's next play, Death of a Salesman, Keller seems to have brought his troubles upon himself. Cariou gives him a hale fellow bravado that goes appropriately dark when things begin to crash.

His wife Kate (Laurie Metcalf), however, is a human time bomb worthy of O'Neill. Refusing to accept the death of her son, she tyrannically insinuates that point of view onto others. The actress taking on Kate must show a deranged woman as both the victim of fate and her own mistakes. By play's end we will see the method to her madness - the Lady Macbeth hidden in the madwoman. It is probably Miller's most demanding female character because it could so easily become an unsympathetic cartoon. But Metcalf takes this Kate down into her bones. In the role that makes or breaks a production of All My Sons, this performance lifts this one up mightily. Both Cariou and Neil Patrick Harris, who plays surviving son Chris, are good in each unit of their performance, but, for Cariou particularly, the tie-together from peak to valley to peak to valley that he must go through is not as integrated into what we're seeing. Harris, too, has the fireworks when we need them, and works very well with the delightful Amy Sloan as Ann Deever. But the early scenes of casual interaction seem almost too distant.

As a little mirror to the audience, Miller at one point allows us a momentary sense that things will be okay. Near the end of the play, it seems the family has dodged the bullet and will in fact pull out of its nosedive. But that sense of relief is merely designed to remind us that we, too, would just as soon live in denial and avoid the hard truths that require painful correction. Miller won't let us off so easily. Less than a minute later, he sends the Kellers -- and with them the audience's hopes -- hurtling down in flames.

top of page

ALL MY SONS

by ARTHUR MILLER

directed by RANDALL ARNEY

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

April 11through May 21, 2006 (opened April 19)

(Opened 9/20, rev'd 9/21m)

CAST Sterling Beaumon, Len Cariou, Chris Payne Gilbert, Neil Patrick Harris, Laurie Metcalf, Megan Austin Oberle, Liam Christopher O'Brien, Robin Riker, Morgan Rusler, Amy SloaN

PRODUCTION Robert Blackman, set; David Mickelsen, costumes; Daniel Ionazzi, lights; Richard Woodbury, sound

HISTORY Premiered in 1947 on Broadway (328 performances); won Tony Awards for Best Play (over The Iceman Cometh and director Elia Kazan (to whom it is dedicated). Starred Ed Begley

Neil Patrick Harris, Laurie Metcalf, Len Cariou

Michael Lamont

Amoré and the Armory

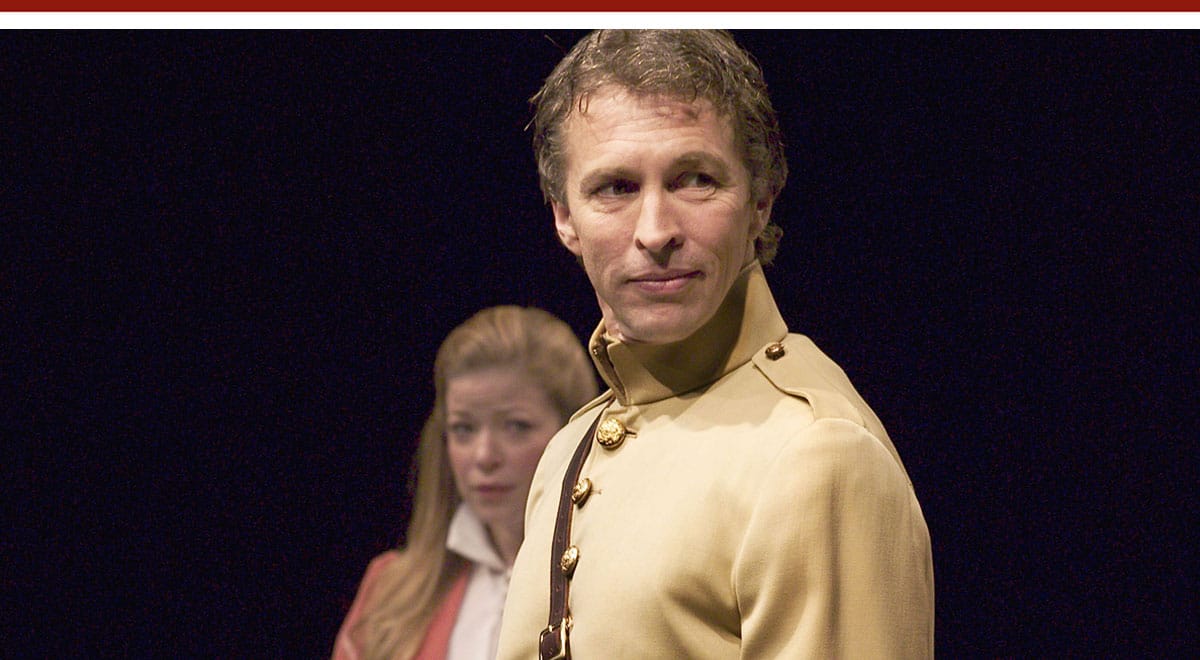

Glendale's A Noise Within is giving Shaw the kind of airing he would have loved: lots of focus on the language. A nice thing about repertory theater is that it tends to straight-jacket the production team into lowest-common-denominator design. In the case of Arms and the Man, now sharing a raked rectangle through May 20 with Ubu Roi (ends May 7) and The Tempest (continuing to May 21), there isn't much to get in the way of the actors and the story.

As with Major Barbara, Shaw is dealing with "arms" meant for amoré as well as the armory. But here the accent is on the romantic, making this play one of his most embraceable comedies. We begin in a bedroom in the finest home in Bulgaria. Bombs may be bursting beyond the shutters, but young Raina Petkof (Dorothea Harahan) assures her mother that the approaching enemy does not concern her. As she is betrothed to a dashing major in the Bulgarian militia, Sergius (Mark Deakins), she has touched gallantry first hand and knows the insurgents will be defeated. But, even if they do get close, she can blow out the candles and burrow under her blankets, because Sergius will save her soon enough.

Shortly after her mother is persuaded to leave, the gunfire moves into her yard and an enemy soldier (Mikael Salazar) stumbles in through her balcony window. Equally frightened, they lock in a stand off, trading threats of disclosure and death until the argument reaches a draw – that of his sidearm, giving him the upper hand. As tempers cool, they get to know each other, and so begins Shaw's thesis that the people who promote war are the civilian amateurs, whose heads are filled with heroic misconceptions, and not the wiser, battle-weary pros.

Mr. Salazar brings an engaging Gary Cooper plainspokenness to the role of Bluntschli, the 'chocolate creme soldier,' while Ms. Harahan blends the right amounts of heart and backbone to her characterization. She may, however have buried Raina's developing infatuation with Bluntschli a little too far beneath the covers. The revelation that she's sent him what amounts to a statement of affection, should seem unexpected, but not impossible.

A side story between the servant who would be shopkeeper, Nicola (Paul Taviani), and the fiery Serb servant girl, Louka (Abby Craden), is well played. Nicola is betrothed to Louka, but will happily trade the potential for romantic security for the potential for financial security. This makes Nicola, as one character says, "the ablest man in Bulgaria." Shaw is saying, with comic resignation, that lover and warrior inevitably kneel before the businessman.

top of page

ARMS AND THE MAN

by GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

directed by MICHAEL MURRAY

A NOISE WITHIN

through May 20, 2006

CAST Mark Bramhall, Radick Cembrzynski, Ronnie Clark, Abby Craden, Mark Deakins, Dorothea Harahan, Mikael Salazar, Karen Tarleton

PRODUCTION Susan Gratch, set; Julie Keen, costumes; James P. Taylor, lights; MK Steeves, wigs

HISTORY Premiere April 21, 1894 at the Avenue Theatre in London's West End. First published in 1898 as part of Shaw's Plays Pleasant volume, which also included Candida, You Never Can Tell, and The Man of Destiny.

Dorothea Harahan, Mikael Salazar

Craig Schwartz

Unlocking the past

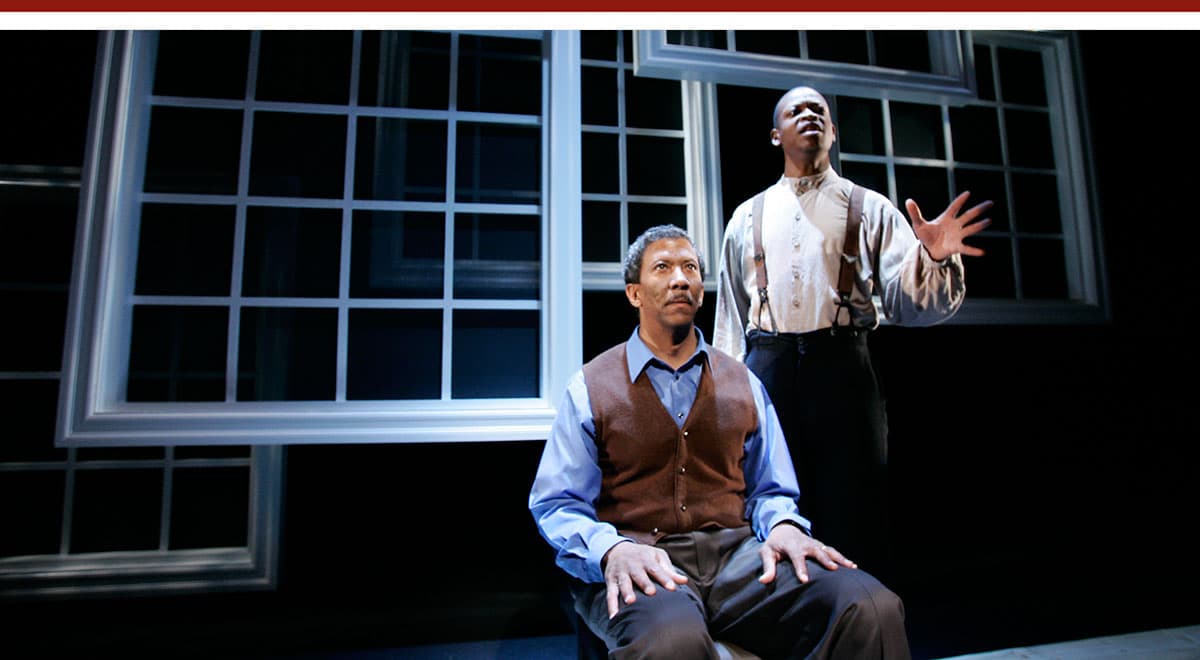

It's unclear what is behind Tanya Barfield's Blue Door, now receiving its world premiere at South Coast Repertory as part of the theater's Pacific Playwrights Festival. On the surface it is a simple story about the need to explore and embrace the stories that got us here, and not excise those earlier chapters that are embarrassing or inconvenient. Inside the play, this simple story proves roomy enough to go in several directions – some in diametric opposition. These isometric pressures created by the plot along with some inactive time spent in the monologist motif, tend to make Blue Door feel stuck.

The story hinges on the awakening of awareness within a highly educated man who has long suffered detachment from his wife, his racial essence, and himself. He has preoccupied himself with what he calls "striving" – pursuit of academic acclaim in the field of mathematics, which includes the publication of a book of his research, Mathematical Structures and the Paradox of Time.

The play, set in 1995 just prior to the Million Man March on Washington DC, begins with Lewis (Reg E. Cathay) alone on stage, providing a blow-by-blow recounting – in the style of Spaulding Gray or Roger Guenveur Smith – of an argument he is having with his wife. She is angry that he has no interest in the March. He defends his right not to participate. They are, of course, both right, which indicates that the argument is about something else. It's what arguments in relationships are usually about: the relationship. Their marriage has been in trouble for years, Lewis says, quoting his wife. The troubles don't stem from their inter-racial marriage, although Lewis' marriage to a white woman is set up as a possible symptom of how he has attempted to deny who he is. Instead, it comes from the fact that, now that he has distanced himself from who he is, he's not left with much to be. And his wife has chosen this weekend to instigate a One Man March: his, out of her life.

Soon, however, Lewis is visited by the physical presence of three key male family members, all played by Larry Gilliard Jr. – his brother Rex, their grandfather Jesse and their great-grandfather Simon. They all had reasons why they failed to succeed in their time: slavery, post-emancipation racism, and, with Rex, getting trapped in the cycle of poverty and drugs.

It is Simon who connects with Lewis through a story about the unbearable conditions he endured as a slave. Simon admits at one point that he would not have lived a day without his wife. It's an emotional admission that touches Lewis, simply for his lack of anything equaling it. Simon also tells how his family and friends used an old African tradition of painting their door blue to keep good spirits in and dangerous, damaging spirits away. Lewis' embracing of his own inner world ultimately is symbolized by his excitement about bringing back this tradition, and holding on to his spiritual world.

There are a couple of paradoxes to wrestle with in trying to unlock the Blue Door. The first is whether the other male characters are the product of Lewis' imagination, or real spiritual visitations. If it is the former, then Lewis has been out of touch with his unconscious and it is the process of getting in touch with it that moves the play. In this case it's a door of perception he needs to open, or remove all together. That might indicate that the blue is sky revealed by the door's removal. If it is the latter, then the spirits of his male family members are really visiting him. If so, he would seem to be so much in touch with that world that painting the door may not be all he needs. He may want to install dead bolts – to keep out the dead.

The spare, perfectly symmetrical set features a large, multi-paned window hanging upstage center. In front of it, center stage, is a single wooden chair. On either side, in mirrored opposition, are two rows of rough wooden risers like something from a slave auction, or at least a 19th Century sidewalk. And, tucked upstage of the risers are, again, mirroring each other, a tidy end table with lamp and reading chair.

As it is always worth remembering, the institutionalized dehumanizing of black people in this country succeeded in making not just those participating but also those ignoring it less than human. If every play written from now till rapture recounted these practices of selling, raping, whipping and killing individuals, and splitting families at a whim, it wouldn't begin to wash the bloodstains out of this country's history books. While Barfield adds to this literature, she is also doing something more, making more general statements about behavior.

But it feels a bit turgid for something so full of passion. A rare crack of electric potential occurs when Rex, for whom she seems to feel more respect than Lewis (the same name as the man who created the Million Man March) identifies the audience. In another example of his disconnect, Lewis doesn't know we're out there. Not only are we, we're virtually all white. Rex chides him for not seeing us: these aren't the people who can reflect what you need, he suggests. In that threat of confrontation, the play becomes most alive.

Ultimately, Lewis' crime is not that he moved so far into a white world. It ís that when he packed for the move he forgot to put his soul in his bag. As he puts it, "I wanted to strive . . . and in order to strive, you can't look back." As Barfield puts it, though not without some movement problems of her own, all you're likely to get by not looking back is hit in the ass by a slamming door when lose the key to your home or heritage.

top of page

BLUE DOOR

by TANYA BARFIELD

directed by LEAH C. GARDINER

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

through May 14, 2006

CAST Reg E. Cathay and Larry Gilliard Jr.

PRODUCTION Dustin OíNeill, set; Naila Aladdin Sanders, costumes; Lonnie Rafael Alcaraz, lights; Jill BC Du Boff, sound, John Glore, dramaturg

HISTORY World Premiere

Reg E. Cathay, Larry Gilliard Jr.

Henry DiRocco

Lighting the way

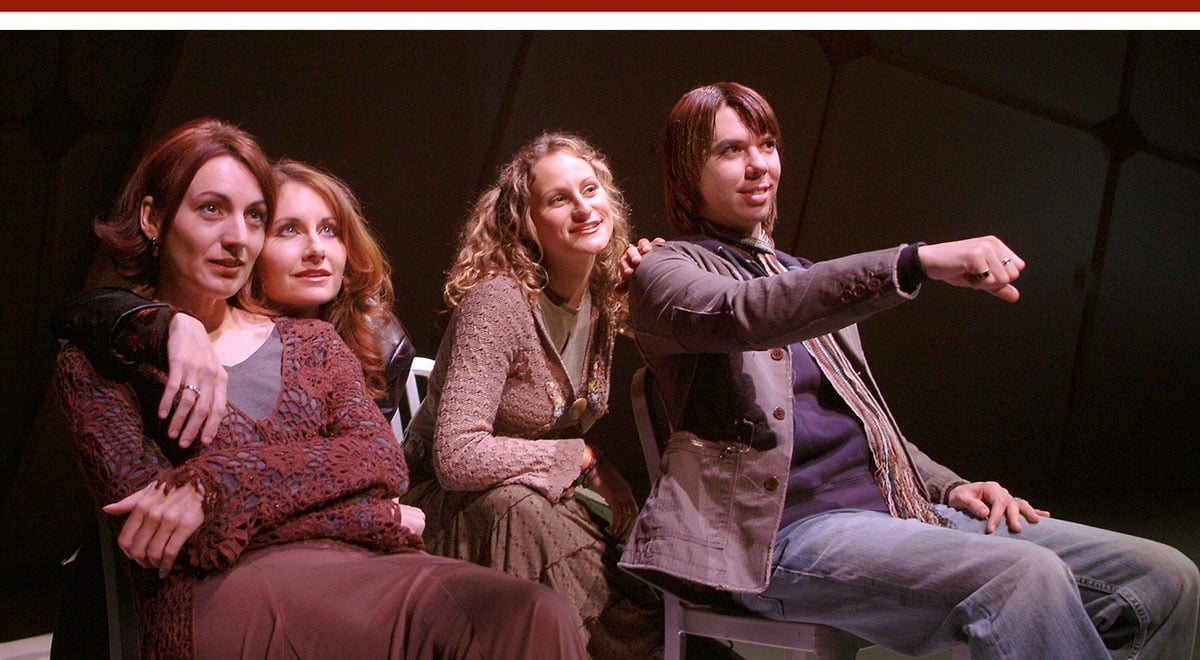

Bryony Lavery's Last Easter takes place in three kinds of overlapping light: one created by theater lights, one created in hindsight, and one created at the far end of the tunnel into the next world. In duly illuminating its several strengths, Director Richard Stein, his actors and designers can't avoid revealing the play's ultimate weakness, an undercutting reliance on light comedy.

In a story about how the terminal illness of one person plays out among her circle of friends, it is logical that the characters ease their pain – or deny it – with jokes and asides. The jokes and asides are such a big, successful part of one performance that it takes on its own life as a crowd-pleasing stand-up act, certain to win over audiences, as it did on opening night. But Lavery's script doesn't know when to pull up from the low comedy and as a result, even at the inevitable conclusion of the tragic story of a woman dying in her prime, we're still getting peppered with one-liners. This may be what has kept the script from being taken more seriously since its world premiere off-Broadway in 2004 – the only production prior to this West Coast premiere.

A memory play told by theater people, it takes place in artificial light and time. The minimal set sports but four metal chairs, moved about the spotlight-pool oval of stage floor to create restaurants, car interiors, church pews and so on. Two huge scenery flats, their bare backs to the audience, hug the upstage wall at angles reflecting the spotlight beam. The two acts are set around two Easters a year apart, but one set of costumes are all the characters need for this twilight world of transitions.

The four friends are June (Helen Wassell), a lighting designer diagnosed with secondary cancer; Gash (Kelly Mantle, a cross between his uncle Mickey and Tommy Tune), an irrepressible performer with a female impersonator's repertoire of musical numbers; a props maker named Leah (Yosefa Forma); and a depressive actress named Joy (Kirsten Chandler), who is haunted by the spectre of Howie (Jay Skovec), a former boyfriend who took his life some time earlier. Each of June's friends is a watered-down version of some religion -- Gash Catholicism, Leah Judaism, Joy Buddhism – offering an ecumenical collection of faiths wrestling with death.

The story of an artist surrounding himself with friends to usher him out in style was told with such depth and honesty in the French-Canadian film The Barbarian Invasions (2003), that Lavery's stage version is modest in comparison. What she has done instead, particularly in Stein's helpful vision, is work the theatricality of the subject, juxtaposing that tunnel light with Fennell light.

Wassell is a great choice for the role performed in New York by Veanne Cox. Wassell really is British, which gives her solid performance real substance, free of any sympathy-soliciting. The others are capable, too, with Mantle getting to put on his own show within a show, offering what for some will be the show's highlight, and for others too much of a good thing.

Lavery means for Last Easter to refer to the most recent observance of the religious holiday, and alternately to the final observance. For June, last Easter was the last. For those she leaves behind, it may or may not get revived. Unfortunately, the feeling at the end of Last Easter is that not much had impacted the survivors' lives. Their shows must go on.

top of page

LAST EASTER

by BYRONY LAVERY

directed by RICHARD STEIN

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

through May 21, 2006

CAST Kirsten Chandler, Yosefa Forma, Kelly Mantle, Jay Skovec, Helen Wassell

PRODUCTION Narelle Sissons, sets; Dwight Richard Odle, costumes; Tom Ruzika, lights; David Edwards, sound

HISTORY West Coast Premiere

Helen Wassell, Kirsten Chandler, Yosefa Forma and Kelly Mantle

Ed Krieger

Blown sideways

Shakespeare's The Tempest is by many accounts the Bard's penultimate work, coming at the culmination of his career and the height of his powers. At the center of both storm and story stands his final creation, Prospero, the rebuked Duke of Milan. Prospero saw his reign fall hard 12 years earlier when a coalition usurped his political powers and set him adrift with a 3-year-old daughter, Miranda. During the years they were presumed dead, they have instead grown wiser, purer and more powerful in other ways. Similarly, this third leg of A Noise Within's 2006 repertory season – alternating with Arms and the Man and Ubu Roi through May 21 – shows the company's powers to create a beautiful production that belies the restrictively small stage and light rigging. Unfortunately, a key performance does feel constricted, which prevents the magic from really taking hold.

While on the island, Prospero (Robertson Dean) has gained the upper hand over two powerful beings – one of the mystical realm and one of the physical. The spirit, Ariel (Michelle Duffy), has given him a different kind of sovereignty. Through her, he has the creative powers to summon the seas, blend in with the scenery, and script the movements of people. In short, the kind of powers a theater writer, director and producer enjoys. Shakespeare, it's worth noting, had set down in the Globe theater 12 years before The Tempest began.

As the play opens, Ariel has whipped up a maelstrom to scatter the ships of a passing fleet from Milan. The lead vessel, carrying the very conspirators who ousted Prospero, winds up tucked in a harbor on Prospero's island. Over the course of the play, love, comedy, wit, retribution and forgiveness will be orchestrated by the mighty governor of this rocky stage, in celebration of the magic, sorcery, theatricality and language that had made Shakespeare prosperous. Dean, while delivering a capable and articulate rendering of Prospero, has an opaqueness he can't rise above. What should be a man of unfathomable breadth, insight and imagination, just seems unfathomable.

Working with him as Miranda is Dorothea Harahan, pressed before opening into double duty with her lead role as Raina in Arms and the Man, and serving both plays well. Ariel is the agile and musical Michelle Duffy (part of the upcoming Mark Taper Forum fund-raiser). Tucked into the cast as King Alonso is the wonderful Mitch Edmonds, who gives his small part the kind of subtleties and depth one would want in the person of Prospero.

top of page

THE TEMPEST

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by GEOFF ELLIOTT

A NOISE WITHIN

through May 21, 2006

CAST Mitchell Edmonds, Richard Soto, Robertson Dean, Dwight Bacquie, Jason Chanos, Harris Berlinsky, Stephen Weingartner, Bo Foxworth, Ray Porter, Kim Swennen, Michelle Duffy, Carlos Larkin, Suzanne Jamieson, Radick Cembrzynski, James Foster-Keddie, Noelle Francis, Elaine Mani Lee, Schuyler Scott Mastain

PRODUCTION Darcy Scanlin, set; Jennifer Brawn Gittings, costumes; Peter Gottlieb, lights; Ron Wyand, sound; Charlotte Purifoy, wigs/make-up

Bo Foxworth, Ray Porter and Stephen Weingartner

Craig Schwartz

Personal assistance

In her early 30s, playwright Joanna McClelland Glass was a secretary to Judge Francis Biddle, the former U.S. Attorney General best remembered as Chief Justice for the Nuremberg trials. Her play, Trying, ostensibly a portrait of Biddle as a fusty old national treasure, is an intimate look at how a person hired as a mere clerical assistant winds up assisting someone in life's most difficult transition.

Richard Seer's beautiful staging on the Old Globe's Cassius Carter Centre Stage, also provides a late-career showcase for the talents of Jonathan McMurtry as Biddle. The veteran of more than 170 productions at this theater alone, bears the weightier line-load in a two-and-half-hour two-hander, and earned a loving standing ovation for his performance on opening night. Among those applauding was co-star Catherine Marie Brown, who, as 25-year-old Sarah Schorr – the Glass alter ego – exacts a nuanced, natural performance, as convincing in her early scenes of eager willingness to please as in later scenes of confrontation and taking charge. Stages she smoothly transitions between.

Biddle is a creature of obsessive habits. Within the office where the two will work, he strictly controls the heat, the placement of every item, and particularly the use of language. Language is their common love. But while Sarah embraces words to one day serve her art, Biddle uses them as excuses to rage against the deterioration of culture.

Their bonding through language begins with poetry, and then through the correspondence and memoirs that Sarah forces Biddle to address. He doesn't seem to be aware of it, but Biddle needs to be reassured that his exit from this world will be grammatically correct. People become memories, certainly. But memories are the first to fade along with the survivors who bear them. Better are photographs. Better still, are written words. People ultimately may simply be words in an address book ("The Bs are all dead," Biddle notes while looking for someone in his) or in vitae, wills and codicils, memoirs and biographies. Biddle already has one lengthy biography to represent him. Sarah reveals that she has taken the initiative to read it.

"You read the entire thing?" he repeatedly asks. And when he presses further, "Cover to cover?," he is really saying "cradle to grave."

The railing over word use, heat settings and thermos placement, we soon realize, are covers for his true rage: that directed at what the poets call the "dying of the light." Despite his bravura announcement on Sarah's first day that he will die within the year – "the exit light is flashing and the door is ajar," he says – he has not come to terms with his mortality. Like a sinking ship's sonar signals, his constant outbursts are probes for something solid. The berating of his assistants has been a search for one who will stand fast. With Sarah, the breaking point only comes when he steps over the line of decency. Her abrupt decision to leave, he realizes, is not weakness but strength. He realizes, in McMurtry's pivotal moment, that she is principled, and at this moment, the stronger of the two. He begs her to stay.

At that turning point in the first act, he begins to shift his weight from his railing against the world, to the support rail that Sarah can offer him out that gaping exit door.

Biddle eventually softens enough to use the new-fangled Dictaphone to record notes after Sarah's shift ends so that she can type them the following day. Here, Biddle cleverly becomes a short, sweet bouquet of sentences for Sarah to keep. After he has exited she discovers the tape. The words are of gratitude and encouragement, the stuff by which he wants to be remembered. Apparently, if we're lucky, life can transition into words. If we're really lucky, into art.

Glass, Seer, McMurtry and Brown have made the late Francis Biddle very fortunate indeed.

top of page

TRYING

by JOANNA McCLELLAND GLASS

directed by RICHARD SEER

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

April 15-May 21, 2006

(opened April 20)

CAST Jonathan McMurtrey and Christine Marie Brown

PRODUCTION Alan E. Muraoka, sets; Charlotte Devaux, costumes; Chris Rynne, lights; Paul Peterson, sound