FEBRUARY 2006

Click title to jump to review

HITCHCOCK BLONDE by Terry Johnson | South Coast Repertory

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST by Oscar Wilde | Ahmanson Theatre

THE PRICE by Arthur Miller | A Noise Within

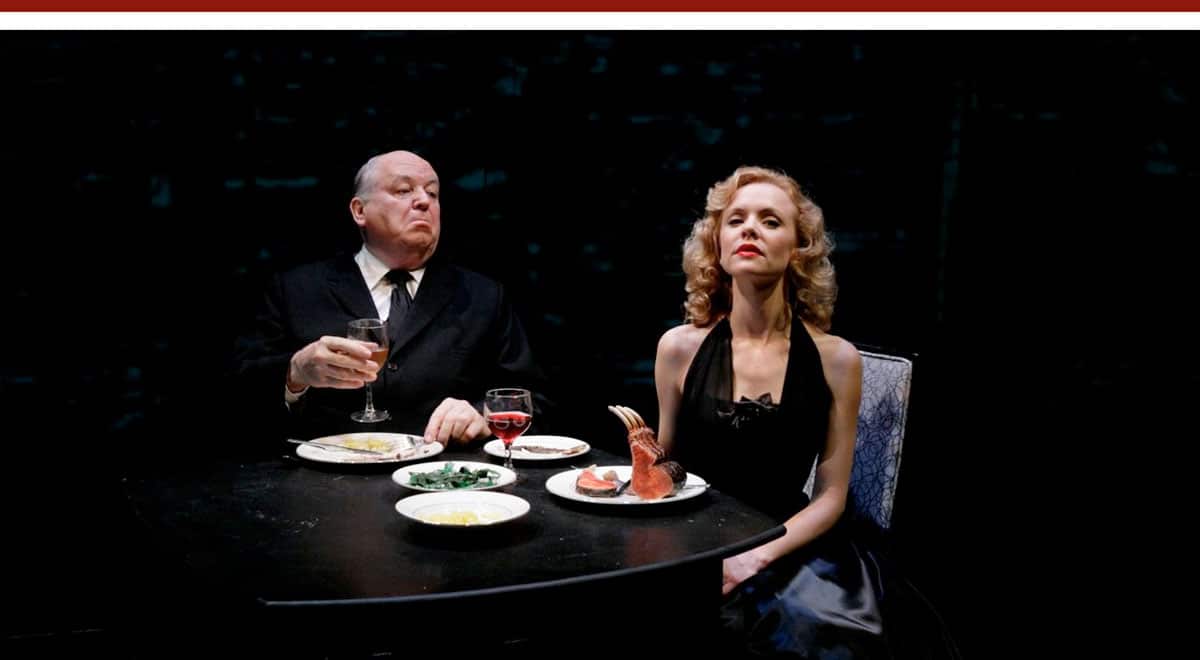

Blonde ambition

In Hitchcock Blonde, Terry Johnson has more to say about sex than he does about cinema. He says it with his own great writing, with the visual images of scenic designer William Dudley, who does more than anyone here to play with the relative dimensions of film and stage, and the score and sound design of Ian Dickinson, who beautifully evokes those historic scores of Alfred Hitchcock's classic films.

The true setting of this American premiere, however, is that messy border region of sexual relations that spawns violence and voyeurism. This is a lawless territory of extremes we know is out there but prefer to pass with the shades drawn. Hitchcock Blonde, in attempting to get in close enough to show its extremes of behavior, language and character, suffers a little from the exposure.

There are three male-female relationships here, none of them healthy. One of the three is sanctified by marriage, but it is the most toxic. Men here, whether famous or fictitious, use positions of social and professional power to engage and seduce women – generally younger – in vague pursuit of peace and pleasure. Once they get it, they lose interest or develop impotence. The world of fantasy and the imagination work into the equation, with film-making an obvious bastion for escapists on both sides of the screen. For their part, the women have surprisingly few reservations to overcome as they slide under the spell. But to their credit they are more capable of honestly exploring the new worlds in which they find themselves. It falls to the women to bring sexuality and its politics out of the projection booth and into the light. And should the power pendulum briefly swing their way, they may find themselves the easy target for violence.

The twin plots – one driven by art, the other by science – are undercut by fraud or lechery – or both. In a twist on Stoppard’s Arcadia, the contemporary story is an investigation of something in 1919 that could shed light on the contemporary story, set in 1959. Here the detectives are using the damaged contents of a stack of mislabeled film cans to investigate a mystery involving some Hitchcock outtakes of great potential historical value.

They may discover whether the reason Hitch cast blondes (or converted brunettes) as his leading ladies because of some dark obsession, or because they just looked better on black and white film. But it is unlikely that’s what is driving Johnson, who used historical figures in both his Insignificance and Hysteria. It is more likely that he is intrigued by the larger issues of men, women, sex, imagination, art and truth. Unfortunately, he seems to have stacked his deck with too many cards of the same suit. Without someone to provide a moral compass, these folks all seem, well, insignificant.

Whatever Johnson's obsession -- which we'll assume is not casting blondes and brunettes in compromising theatrical roles -- Hitchcock affords him a chance to flex his considerable writing muscle. The most potent speeches seem to come from a middle-aged man spinning his web of empathy before a young lady. Within the mystery of the mystery, there are beautiful paradoxes to chew on, such as the body double who ironically allows a sense of intimacy with the star, or the man who claims his eyesight is getting better with age, and that is why he needs more pairs of glasses.

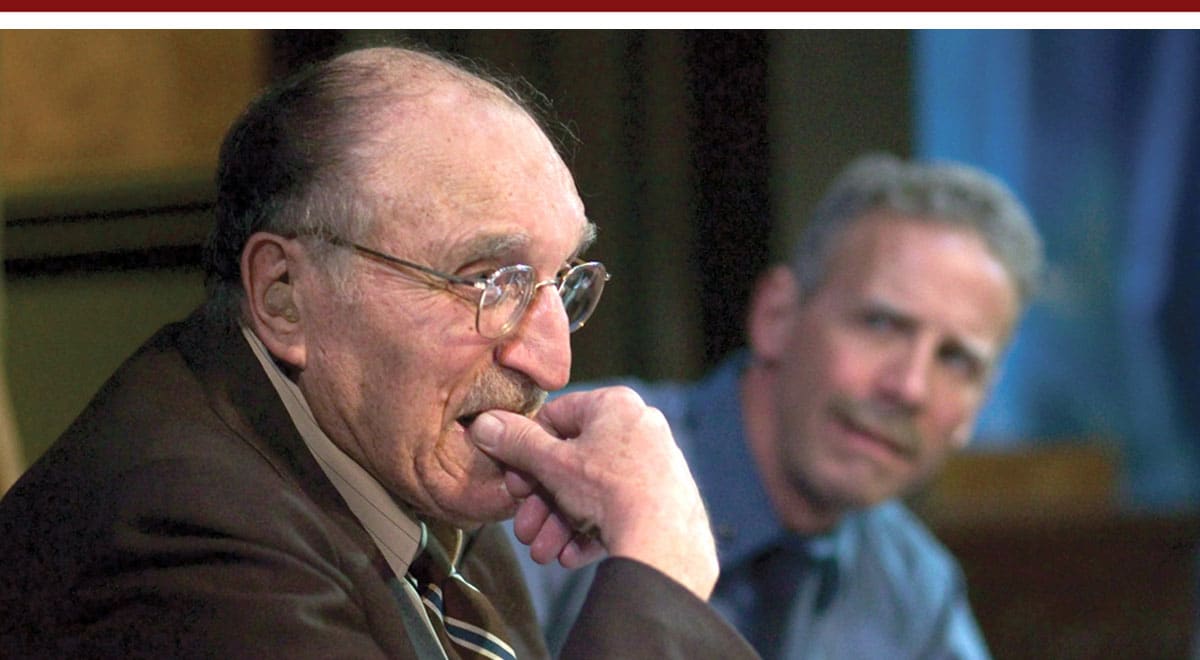

Regardless of what this play needs, it benefits from a scenic concept worthy of the operas that are Dudley's usual milieu and a lovely – if leering – portrait of Hitch by Dakin Matthews. Also kudos to Robin Sachs and especially Sarah Aldrich, who’s got to be the bravest actor on this season’s roster.

Whether it cautions or entices, the reader should know there is full female nudity, violence, and the kind of language that inevitably heats the seats of a couple couples per performance and sends them scurrying for the safety of their SUVs.

top of page

HITCHCOCK BLONDE

written and directed by TERRY JOHNSON

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

February 3 - March 12, 2006

CAST Sarah Aldrich, Adriana DeMeo, Dakin Matthews, Martin Noyes, Robin Sachs

PRODUCTION William Dudley, set, costumes, video; Chris Parry, lights; Ian Dickinson, composer/sound; Ian Galloway for Mesmer, video realization; Magdalena Zira, assistant director; John Glore, dramaturg

HISTORY American Premiere

Dakin Matthews, Sarah Aldrich

Ken Howard

An 'Earnest' effort

The Importance of Being Earnest, Oscar Wilde’s 1895 comic celebration of superficiality, spins layers of colorful language around a plot as tightly wired as a dresser’s dummy. When properly turned out, the effect is an evening both perfectly shaped and perfectly silly.

The first time one sees a definitive production of the play, he or she is likely to be as spontaneously and helplessly smitten by it as its characters are by one another. The production that opened this week at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles (through March 5) has the power to provide that revelatory experience for those still in need, thanks in great part to Lynn Redgrave. Despite having the least stage time of the major characters, hers insinuates that while Earnest may be important, Lady Bracknell is quintessential.

In Redgrave’s two scenes, she commands the stage as justifiably as she commands the billing. She is, as one of Wilde’s characters describes her, the only one who “rings the door bell in Wagnerian fashion.” Two stand-outs in the capable cast are Miriam Margolyes as a cartoonish Miss Prism who tutors Cecily with oratory flourish, and Robert Petkoff, who brings the bearing of a giddy younger Branaugh brother to Algy.

Director Peter Hall and his designers have minimized their set. Assuming it’s not because a crate of stage dressing is still at the dock, it’s a welcome focus on the actors and their words. In any event, it is the words that make the play timeless. Wilde has fed his characters mouthfuls of bons mots to punctuate conversation and give the play percussion. Yet in many sweet phrases are buried nuggets of irony that bear the sting of truth. Lady Bracknell offers one that could be the parenthetical subtitle to the play, turning out its satirical title: “We live, I regret to say, in an age of surfaces.” True then. True now.

top of page

THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST

by OSCAR WILDE

directed by PETER HALL

AHMANSON THEATRE

January 17-March 5, 2006

CAST Lynn Redgrave, Miriam Margolyes, Terence Rigby, Bianca Amato, Charlotte Parry, Robert Petkoff, James Waterston, Geddeth Smith, James A Stephens

PRODUCTION Kevin Rigdon and Trish Rigdon; Sound Design, Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen

Lynn Redgrave and Robert Petkoff

Craig Schwartz

Song of Soloman

A Noise Within’s production of Arthur Miller’s The Price made a six-performance return run in early February 2006. It was the Glendale company’s third remounting in as many years, all with the cast of Robertson Dean, Geoff Elliott, Len Lesser and Deborah Strang. Elliott and co-Artistic Director Julia Rodriguez Elliot directed.

The production is a great introduction to play and playhouse, which work well together to put their advancing years in mutually flattering light. The house, which A Noise Within has made noises about abandoning, is a hunched room of aging theater seats and patrons. The set is the cluttered upper room of an abandoned home, where a family had retreated with furniture and memories as bankruptcy, then paranoia and finally death claimed its patriarch.

While Miller is arguably the American playwright of the 20th Century, his plays were having diminishing impact by the time The Price premiered in 1968. His early masterpieces Death of a Salesman, All My Sons, The Crucible and A View from the Bridge were a hard act for even him to follow. But the scripts of the 1960s – The Misfits, Incident at Vichy, After the Fall and The Price – hold up against any writer’s second shelf of work. A Noise Within’s production shows how much even a lesser-Miller work has to offer.

The Price explores Miller’s usual themes of family, honor and death, but represents the first work following the death of the writer’s father in 1966. The play’s characters echo the four-cornered family from Salesman, but with the brothers now middle-aged and the dead parents replaced by one brother’s wife and an indomitable old Jewish businessman who is the father figure Miller has long been waiting to love. There are other stand-ins for the parents amid the room’s furniture and clothing – most importantly the father’s empty chair and several of the mother’s evening gowns.

Vic (Elliot) is the policeman son who sacrificed a career in science to stay home and nurse his once-successful father through his final decline. Walter (Dean) left years ago to become a wealthy, influential surgeon. The house has sat empty since the father died a few years earlier and now, with the property slated for demolition, Vic has asked an appraiser to come by with a price for the contents. Before the break, Walter, who has ignored a week of phone calls from Vic asking him to share in the memories, decisions and profits, and Vic’s wife Esther (Strang), arrive to meet the ancient appraiser, Soloman (Lesser).

The acting is uniformly fine and engaging. (Hence the repeated retrieval from storage of Michael C Smith’s set and Angela Calin’s costumes.) But the revelation is Lesser, playing the 90-something Soloman with the kind of weary valiance that comes with being a seasoned pro of 85. In the same way the play and the theater bring each other to life, Soloman and Lesser clearly combine to make their moments of oneness some of the best either has had. Miller is surely smiling whenever Lesser is onstage.

For Miller so loved this character, that he gave him the special name of Soloman, representing ultimate wisdom in sorting out the affairs of man. Lesser, who must maintain suspense in the play by balancing his character between pro and con, does so beautifully. Soloman adheres to a strict morality, though Walter and Esther don’t believe if for a minute. Vic does, but he’s long been dismissed as a push-over. Part of what gives Soloman his drive is the loss of his only daughter to suicide. This leads to one of the play’s major themes – the ‘price’ of loss. That loss is manifested by the survivor’s ability to ‘see’ the departed. Soloman sees his daughter every night as clearly as if she were seated before him. Similarly, Vic and Walter can still see their father in his chair. Vic, however, cannot summon up an image of his mother, and for her part Esther says many times, “I can never believe what I see before me.”

ON THE REAL SIDE. After the Sunday matinee I attended, I exited the old hall into the late-afternoon clarity of a bright winter day. The heat’s thin air had allowed the mountains to inch closer down Brand Avenue and the San Fernando Valley wore a Welcome Home. Glendale’s maintained architecture made it feel like a town that understood itself, and I rolled down all the windows to let that spirit fill my dirty sedan as I rolled through the long shadows to the 134, and my first trip out to my parents’ now empty home, to continue the work of clearing out all they could not take with.

top of page

THE PRICE

by ARTHUR MILLER

directed by JULIA RODGRIGUEZ-ELLIOT

A NOISE WITHIN

Ends February 5

CAST Robertson Dean, Geoff Elliot, Len Lesser, Deborah Strang

PRODUCTION Michael C. Smith, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes