FEBRUARY 2008

Click title to jump to review

JOAN RIVERS: A WORK IN PROGRESS BY A LIFE IN PROGRESS by Joan Rivers and Douglas Bernstein & Denis Markell | Geffen Playhouse

RED HERRING by Michael Hollinger | Laguna Playhouse

THE SEVEN by Aeschylus, Will Power (book, music and lyrics), and Will Hammond and Justin Ellington (music) | La Jolla Playhouse

SOME GIRL(S) by Neil LaBute | Geffen Playhouse

VOICES FROM OKINAWA by John Shirota | East West Players

Facing the facts

Many of television's pioneer comics closed their acts by taking off the mask – removing the bit as it were – and speaking from the heart. After taunting and humiliating his audience, Don Rickles told them how much he loved them. Red Skelton simply slid from simpleton to sap, capping his clowning with a tearful "God Bless." Now, in the Geffen Playhouse world premiere of Joan Rivers: A Work in Progress by a Life in Progress, the 74-year-old comedienne is dropping her facade – one she'd be the first to admit is stretched pretty thin – and baring her soul in a self-administered, sleight-correcting lifetime achievement award.

With co-writers Douglas Bernstein and Denis Markell to help dramatize her personal and professional life story and director Bart DeLorenzo to keep it moving, Rivers shows that her stand-up chops are still razor sharp, her ability to engage an audience with stories alternatively heart-wrenching and hilarious is superb, and her acting abilities are more than sufficient to handle the theatrical crown-of-corn contrivance into which her gems of remembrance are set.

While the play structure is the weakest part of the intermission-less, hour-and-fifty-minute show, it doesn't get in the way of showcasing Rivers' in-your-face, nothing-is-off-limits comedy. But it also relies for plot twists on an embarrassing, demeaning bit of anti-defamation defamation, which it would be nice to cleanse itself of before New York. The play is loose enough to let Rivers break the fourth wall and stand and deliver what made her famous. Sparked by subjects raised in the script, she moves into spotlight while her co-stars wait in the upstage darkness, and engages the audience, nightclub style, delivering a mix of comedy and real-life anecdotes. Her jokes elicit what currently must be the biggest legitimate laughs in any legitimate theater, while some of the stories recount episodes of utter despair. Together they earn this trifle of a play some serious comedy-tragedy masks.

The other value here is historic. For those who remember how the worlds of television, nightclubs and showrooms turned a generation ago, Rivers' place in those worlds, and how she slipped to be ground between them, is described in real terms. And, with a minimum of self-pity. In the years between Lucy and Lily, long before Rivers became a poster-girl caricature for plastic surgery excess, a Red Carpet Harpie and a QVC huckster, it was she who insured a woman's place in the fiercely maintained boys' club of the tv variety shows. Along with only two others we remember – Phyllis Diller and Totie Fields – Rivers was far and away the funniest.

Regarding her celebrated surgery choices, audience members who wonder, "Does she know how weird she looks?", will find that straight-faced septuagenarian digs right in and tackles the issue as soon as the topic elicits a titter. "This is not a nightclub," she shouts back in her unforgettable brassy, chiding voice, "This is not cheesy old Las Vegas. This is theater. And you don't do plastic surgery jokes in the theater!"

Then, naturally, she unleashes a stretch of hilarious observations on surgery and why women have it. In Progress takes place in Rivers' Oscar telecast dressing room as she gets ready to go live on the "Red Carpet" with her daughter Melissa. In real life the Riverses have mapped their own corner of Red Carpet coverage, offering a combination of fashion savvy and catty commentary for E! Entertainment. As she gets ready, Rivers needles, confides in and befriends the two strangers assigned to help her: Kenny, a hapless associate producer from the network (Adam Kulbersh) and make-up artist Svetlana (Emily Kosloski), a Russian-accented throwback to comedy stereotypes from Dagmar to Carol Wayne.

To get the Geffen audience in the mood, Blake (Leo Marks) and Chase (Dorie Barton) had been stationed in the lobby as greeters, critiquing and complimenting arriving theatergoers on our apparel, and asking Rivers' trademark: "Who are you wearing?" Once inside, we picked up on Blake and Chase, on the projection screen above Tom Buderwitz's set, in a pre-recorded tape that shows them interviewing daughter Melissa in her only appearance in the show.

While there are little sitcom-level problems that threaten Rivers arriving on time for arrivals (make-up artist has little experience; Rivers' dresses are destroyed by associate producer), the main tension that drives the story is the creeping awareness that Rivers' career – which triumphed over sexism – is now facing cancellation due to ageism. A beautiful new network exec (Tara Joyce) arrives late in the play to lay down her new order, which will dump Old Woman Rivers for a more curvy, current Rivers, Melissa.

In Progress reminds us how funny she was, and tells us just what happened to her. According to her, at a time when her career threatened an historic breakthrough that might have moved her closer to Ball's orbit, she made a selfless, principled stand behind her man. She was handed her head in a bag, and sent to wander the wilderness alone by the new network she'd helped to establish. But you won't hear her whining. Rather, she offers that great showbiz tradition of simply noting the scars, slaps and sleights she took in her life and packaging them to sell back to her audience – people who outside the theater might never have given the plain girl from Brooklyn a double take. But here, in the palm of her hand, are doubled over.

top of page

JOAN RIVERS:

A WORK IN PROGRESS

BY A LIFE IN PROGRESS

by JOAN RIVERS and DOUGLAS BERNSTEIN & DENIS MARKELL

directed by BART DeLORENZO

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

January 29-March 9, 2008

(Opened 2/6, rev'd 2/7)

CAST Dorie Barton, Tara Joyce, Emily Kosloski, Adam Kulbersh, Leo Marks, Joan Rivers, Melissa Rivers (on video)

PRODUCTION Tom Buderwitz, set; Christina Haatainen Jones, costumes; Rand Ryan, lights; John Ballinger, sound/music; Austin Switser, projections; Elizabeth A. Brohm/Christopher J. Paul, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Joan Rivers, Emily Kosloski and Adam Kulbersh

Michael Lamont

If the Shue fits

Ill-fitting shoes are a recurring problem in Michael Hollinger's Red Herring, a crazy, noir-inspired comedy currently receiving its Southern California premiere at the Laguna Playhouse through March 16. However, Andrew Barnicle's well-cast and well-paced staging suggests a playwright who could neatly fill the shoes of Larry Shue, the late actor-writer whose short playlist remains a regional mainstay. Wherein lies the real mystery of Red Herring: Why haven't scripts by this prolific Philadelphia playwright begun to cure commercial theater of its addiction to Doc Simon and the like? The only clue that surfaces, judging from this play, is the writer's inability to rein-in runaway plotlines, that become as hard to untangle as 200 feet of fishing line.

We understand that the "red herring" is a device as well as a title. But Hollinger has loosed a veritable grunion run of them. You'll need a bag of runes and the GPS from your dashboard to follow this Herring through its over-woven story. Still, Hollinger's divine gift for imaginative comedy writing makes it a plunge worth taking. There's enough cathartic laughter in Herring to cheer even the broken-hearted.

But, start with a murder victim who goes by as many aliases as a cat has lives, add characters pretending to be married, double-cast just about everybody, mix waterfronts in Wisconsin, Boston and Bali, and you are just getting started on the confusion. The very loose chalk outline of Herring begins with the dropping of a stiff from Bruce Goodrich's imposing dock set (to the ominous sounds of another fine David Edwards' design) before Boston cop Maggie (Kirsten Potter) and her G-Man fiancee Frank (Brendan Ford) chat about their cases (which may or may not connect). The other shoe drops when Maggie is pulled from the case and a dark secret about her past derails the pair's trip to the altar.

Meanwhile back in Wisconsin, Lynn McCarthy (Traci L. Crouch), dear-but-dizzy daughter of red-baiting Senator Joe McCarthy, is haplessly helping James (Brett Ryback), her All-American Soviet spy of a fiancee, to pass microfilm. Another pair of opportunists, Mrs. Kravitz (DeeDee Rescher) and Andrei Borchevsky (Tom Shelton), are also embroiled to their biceps in the Velveta-thick plot.

So many red herrings begin to add up as missed opportunities. But the jokes are crisp and the actors' delivery terrific. From the opening bedroom banter between Maggie and Frank (paraphrasing: He: "Hey. It's bad form to call another man's name during love-making." She, "I thought 'Oh Jesus!' was the exception.") right through to a noir-style "How You Likes It" finale (complete with mismatched handcuffs), Barnicle's band of players hits every note. Potter (our 2006 Favorite Female Lead for Rosalind in Noise Within's As You Like It) continues to please as Maggie, putting just the right patina on her soft-shelled "flat foot in heels." Crouch is a comic revelation after surviving the train wreck of The Verdi Girls on this stage last year.

In one of the two scenes that most recall the spirit of Shue, Hollinger has written a five-second delay into an international phone conversation between Lynn and James. Crouch and Ryback clearly gave this section extra attention, and still it crackles with spontaneity. Rescher and Shelton, who carry the bulk of the multiple-casting demands, really shine. Shelton, who must do a crazy full-body interpretive dance sign language, keeps his rubber face straight as he gyrates. Ford, too, plays the tough romantic lead, then shifts to silliness for a second role.

What's keeping Hollinger from owning Rialto real estate may be this way he undermines the pleasure of his perfectly sculpted set-ups and one-liners (there are several mis-appropriated responses ala Airplane's "Don't call me surely" gags) with storytelling clutter. He demands both sides of the brain – the fun-loving and the analytical – to run at fever pitch: losing ourselves in laughter while being vigilant for clues. It's like asking Einstein and Larry the Cable Guy to share a rowboat. We know which one is going to steer. And, while Larry heads for Mr. Toad's Wild Ride, whatever Al is saying back in the stern goes in one oar and out the rudder.

The theater could use more comedies that will overflow coffers with cash, and overpower coughers with laughs. Hollinger owes it to himself (and his heirs) to find the next Nerd or Foreigner in his wheelhouse. He obviously is devoted to theater. Why he's writing children's touring shows and not stoking the sitcom machinery is a mystery we hope he never detects. In the meantime, we look forward to his next script. Maybe he can stay in period with a '60s TV show backstage comedy like "The Mel Coolie Mysteries": minimal plot, plenty of laughs, and more heart. Such a play might earn him favored status at theaters across America, who in turn may finally be willing to drop old titles from their schedules like so many stiffs "from the 23rd Floor."

top of page

RED HERRING

by MICHAEL HOLLINGER

directed by ANDREW BARNICLE

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

January 29-March 9, 2008

(Opened 2/6, rev'd 2/7)

CAST Traci L. Crouch, Brendan Ford, Kirsten Potter, DeeDee Rescher, Brett Ryback, Tom Shelton

PRODUCTION Bruce Goodrich, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Paulie Jenkins, lights; David Edwards, sound; Vernon Willet/Jennifer Ellen Butler, stage management

Kirsten Potter and Brendan Ford

Ed Krieger

Sounds familiar

In a pop music world where miniaturized delivery systems are now the size of signet rings, it's telling that the rap and hip-hop artists most in the vanguard have a tradition of incorporating big old vinyl and turntables. Consequently, the image of the disc-scratching DJ (Chinasa Ogbuaga), which kicks off the world premiere production of The Seven, Will Power and Jo Bonney's retelling of Aeschylus' The Seven Against Thebes (through March 16 on La Jolla Playhouse's Potiker Stage), signals that these artists are happy to sample the ancient – equipment and stories –if it can be used to connect with the present.

Here, with credits to Power for book, lyrics and co-composing with Will Hammond and Justin Ellington, and to Bonney for developing and directing, The Seven makes a connection. Like sidewalk sound systems boot-legging municipal power out of a streetlight, the performances channel the essence of the great Oedipus tragedy without having to go Greek.

Not since Gospel at Colonus rumbled through here a generation ago have Americans packed the myths with such muscular music. But where Gospel, a retelling of Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus, stayed within earshot of the church sound, Seven draws on a broader palette, weaving together gospel, work songs, blues and R&B styles. This extends to its freedom to invoke cultural references, from musical icons like James Brown and Robert Johnson to popular tunes like "Shaft" and "Dreamgirls," and on to film touchstones like Freddy Kruger and Jar Jar Binks. There is in fact a brazen "found art" component to rap and hip-hop lyrics that has infused the show's writing with the same promise of non-exclusivity that it wants to project to audiences.

What keeps Seven from descending into a pop-culture mish-mash is vision and unification. When a show both draws from and portrays such variety (not only in terms of its raw materials but also the mixture of sacred and silly), there has to be a strong personality, or tight team, behind it. And, the guess is that Bonney and/or Power have (or has) it together. We are familiar with Bonney from her successful staging of LaBute's Fat Pig at the Geffen: Power is the wild card. If this show indicates that rappers, who we're used to see excel on film as Will Smith (who, it should be noted, began his film career in a challenging adaptation of a play), will help expand the theatrical vernacular, then it's a good day for the stage. Kudos to Christopher Ashley, for another in his young reign's inspired choices.

The Seven is of less use as a scholarly recitation of the events, locations and genealogy of relations and more a visceral embodiment of those relations and the betrayals and curses that powers them. The myth that Aeschylus tells in The Seven Against Thebes focuses on how the sins of the father are rained upon the sons. Certainly inner city residents recognize the cut of bad news bearers from Stagger Lee to Superfly in Bonney's Oedipus (Edwin Lee Gibson). His sons, Polynices (Jamyl Dobson) and Eteocles (Benton Greene) inherit the troubles from dad, just as Oedipus innocently took on the mantle of his father, Laius, after Laius erred: disobeying the oracle by begettin' an heir. Though the brothers begin with every intention to skirt the curse against shared rule by alternating their reigns, greed, suspicion and jeolousy soon undermine their plans and battle proves inevitable. (Polynices gathers seven armies, one for each gate into Thebes, where his brother is currently enthroned, and hence the play's title. Which, scholars tell us, was not the name given it by Aeschylus, but assigned it later from an Aristophanes quote. More errant begetting.)

Like the story, Richard Hoover's set is dominated by twin verticals facing off at center. Two projection screens create changing backdrops for a stage otherwise kept to a simple curved stairway leading to a platform. The DJ remains down right for the entire two-act, two-hour musical. Robin Silvestri is responsible for filling those screens with a theatrical backdrop of beautiful photography and video (abstracted trees, bleeding wounds, black-and-white Bruce Weber actor close-ups, etc.). Musical direction by Daryl Walters and choreography by Bill T. Jones also fit neatly into the creators' vision.

The fine cast has that extra energy of purpose, and they are likely to be rewarded for it with regular standing ovations like the one that concluded opening night. Flaco Navaja is the loving Tydeus, who delivers a radio-ready torch song (wherein lies the Dreamgirls nod), Bernie White is Eteocles "Right Hand," and Charles Turner is the voice of the old storyteller on record. The chorus is Uzo Aduba, Shaneeka Harrell, Postell Pringle, Pearl Sun, and Dashiell Eaves.

The Seven is a fine success at telling a classic story to contemporary listeners, and letting the vinyl and stylus generation sample why, as Q says, "Rap is here to stay." Power, Bonney and crew are bringing it -- and taking it -- home.

top of page

THE SEVEN

adapted from AESCHYLUS (Seven Against Thebes)

book and lyrics by WILL POWER

music by WILL POWER, WILL HAMMOND, JUSTIN ELLINGTON

choreography by BILL T. JONES

developed and directed by JO BONNEY

LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE

February 12-March 16, 2008

(Opened, rev'd 2/17)

CAST Uzo Aduba, Shawtane Monroe Bowen, Jamyl Dobson, Dashiell Eaves, Edwin Lee Gibson, Benton Greene, Flaco Navaja, Chinasa Ogbuagu, Postell Pringle, Pearl Sun, Charles Turner, Bernard Whilte

PRODUCTION Richard Hoover, set; Emilio Sosa, costumes; David Weiner, lights; Darron L. West, sound; Robin Silvestri, video/projections; Shirley Fishman, dramaturgy; Wendy Ouelette/Anjee Nero, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

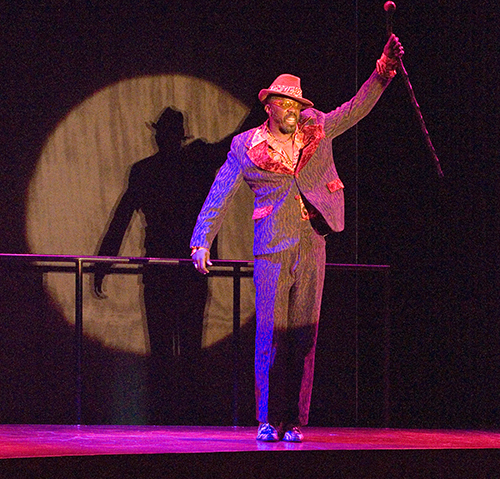

Edwin Lee Gibson

Photo by J.T. Macmillan.

The rake's wake

In three theater encounters not a single Neil LaBute play failed to thrill us. However, with LaBute directing the Geffen Playhouse West Coast premiere of his Some Girl(s), when one might expect the pleasure to be doubled, Some Girl(s) instead seems as lacking in character as the Guy at its center. Despite two performances that nearly disprove the theory, LaBute the writer has not been served by LaBute the director.

What made LaBute's Bash, Autobahn and Fat Pig powerful enough to border on important was the fearless way he presented his gallery of perpetrators and their victims (occasionally as the same person). He gradually revealed his characters under an unflinchingly harsh light, with enough twisted humor to provide us with some guilty-pleasure laughs in the process. In Fat Pig, however, despite the brutal title, LaBute showed signs of lightening up. As we wrote about its West Coast premiere on this stage last May, Fat Pig "seems to settle in more like a contemporary television dramedy with a single storyline and stock characters from hit shows." However, as we also noted, "the kind of menace that LaBute previously employed in his unsettling comedies shadows this story beneath the surface, waiting until the final curtain to rise up and make us pay for our laughs."

Some Girl(s) tends to make us pay instead for our loyalty to the playwright. And, because two performances manage to break through and deliver, one suspects the writing may be less the culprit here than the directing, which was handled for those earlier viewings by Joe Mantello (Bash), Amanda Weier (Autobahn) and Jo Bonney (Fat Pig).

What we have here is, textually, a play that takes a long time to get to its point, fumbles around with it, undercuts it in the final scenes and then leaves us uncertain as to what our central character's central motivation really was. This would not be a problem if the hour-and-forty-five-minute one act had been more interesting or more entertaining. But how much interest or entertainment may lie in the script is hard to know. It has been subverted by a core performance that buzzes with schtick. It is distracting at best; and irritating and misleading at worst.

It would require a lot of dressing to disguise the dullness of LaBute's point that men can be cads and treat women like faceless bust-stops on a bed-hopping life of self-fufillment. We get a poppin-fresh macguffin to help the vaguely familiar plot of a soon-to-be-married writer visiting four former flames in search of their - and his - understanding. However, LaBute can't make his point about men in this narrative device without employing strong women. And, the gimmick is that enough time has passed for them to have changed since they fell for him. But . . . he supposedly has a Black Book full of women like this. So, when credulity is strained to distortion it's hard to swallow the social commentary.

Such a lady's man would be expected to be charming and seductive. But LaBute gives us a nervous, duplicitous, shallow man who has not so much changed as found a way to make his decades-long practice of preying on women provide a healthy annuity.

One enjoyable aspect is the parlor game dimension of the names. Our man gets the generic "Guy" (Mark Feuerstein) while the women all get ambi-sexual names: Tyler (Justina Machado), Bobbi (Jamie Ray Newman), Sam (Paula Cale Lisbe) and Lindsay (Rosalind Chao). Even Bobbi's twin is Billy, or Billi, furthering LaBute's titular statement that Guy(s) see(s) women as interchangable. For older audience members, another game that helps pass the time is the soundtrack of Rolling Stones songs, which while including no songs from Some Girls, offers pre-, post- and intre-scene cues that go back through the past (darkly) beginning with Exile on Main Street.

The theory, apparently, is that by keeping Guy flighty and inscutible, and the women real and grounded, we'll further understand LaBute's thesis. But, of course, even the least aware of these women would likely spot the user in this guy from a good distance. Machado and Newman are strong enough actors to buck the trend and make their characters completely grounded. It makes one wonder how Some Girl(s) would have played if Feuerstein had been allowed to let Guy be not only more real, but appealing.

At curtain call, we're left wondering whether LaBute's twist ending is covering a chance that Guy may have been capable of becoming a human being and relatiing to one of the women as an equal partner. But with a Guy as determinedly thoughtless as this one, it's unlikely very many leaving the theater will give it a second thought.

top of page

SOME GIRL(S)

written and directed by NEIL LA BUTE

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

January 29-March 9, 2008

(Opened 2/6, rev'd 2/7)

CAST Rosalind Chao, Mark Feuerstein, Paula Cale Lisbe, Justina Machado, Jaime Ray Newman (u/s: D.J. Harner, Todd Cattell, Heather Witt, Leslie Connelly)

PRODUCTION Sibyl Wickersheimer, set; Lynette Meyer, costumes; Kristie Roldan, lights; Cricket S. Myers, sound; Mary Michele Miner, stage management

HISTORY Premiered at London's Gielgud Theatre, May 2005; West Coast Premiere

Marc Feuerstein and Justina Machado

Michael Lamont

Dressing makes the meal

Jon Shirota's Voices from Okinawa is the second premiere in this East West Players anniversary season to be written by writers known principally for writing prose. While the first, Dawn's Light, benefited from a singular narrative focus and a single actor (the commanding Ryun Yu), Voices, in Artistic Director Tim Dang's staging, fails to find the power in stories. Veteran Amy Hill alone has the chops to spin her dialogue into gold, providing a vivid characterization that is greater than the sum of the other parts.

Inspired by the author's experiences as a guest lecturer for a friend's literature class in Okinawa, the story gets a nice twist by turning this into an English class and the instructor into an American with an Okinawan grandfather. This sets the stage for a simpler, more open form of cultural clashing. As part of Kama Hutchins' (Joseph Kim) lesson plan, the half-dozen students are encouraged to just talk. Naturally, the stories they tell are more telling than might seem natural for a group of strangers, but it's an acceptable device for our purposes here. And, Dang helps the cause by turning the speaker out to the house, isolating him or her in light, and letting us feel this is as much a look at their lives as a gauge of their language skills.

One pair of students provide the most interesting story, in a broad-comedy skit that carries a heavy wallop. Hitoshi (Atsushi Hirata) and Harue (Teruko Kataoka) are drawn to be performers, and are allowed to do a show rather than just talk. It is weak in plot abidance but beneficial in its entertainment value as these two actors really shine in their moment. Among the others are Takeshi (Taishi Mizuno), Namiye (Mari Ueda) and Yasunobu (Kotaro Watanbe).

Kama befriends Yasunobu (the charmingly goofy Watanabe), who knows Obaa-san, Kama's great-grandmother (Hill), a 90-something survivor living on five prime acres of cane field in the house her husband (who Kama was named for) built.

Shirota's plot weaves together watching the students' progress (and picking up the insights they intentionally slip in or unintentionally let slip) with learning about what will happen back on the farm. An unlikely but inevitable romance between the tightly wrapped matriarchal school principle, Keiko Oshiro (Sachiko Hayashi), and Kama works its way to the top of a relationship initially dictated by Oshiro's insistence that language be taught by rules first rather than conversation. It's an interesting argument, but like most of the show's narrative elements, it lies like a tool on a shelf to be picked up when needed and then set back. Shirota needs a more compelling and pointed element to drive this, and perhaps a less affable and genial lead than Kim's Kama, to lend it some urgency.

The lingering presence of Americans at the nearby base 60 years after the horrifying climax to World War II is the big devil behind the screen. That is the monster we catch glimpses of in the students' stories and in the conflicts Hill's character is having with retaining her property. But the cold realities never seem to leak through the cozy story, and such things as over-mannered storytelling gestured (which thankfully are not insisted upon the final sad tale) are more than these actors can integrate comfortably. If it's a nod to traditional Japanese acting styles, it's doing more harm than good. Like the whole point of the play tells us, the present should not suffer for the past.

top of page

VOICES FROM OKINAWA

by JON SHIROTA

directed by TIM DANG

EAST WEST PLAYERS

February 7-March 9, 2008

(Opened 2/13, rev'd 2/15)

CAST Sachiko Hayashi, Amy Hill, Atsushi Hirata, Teruko Kataoka, Joseph Kim, Taishi Mizuno, Mari Ueda, Kotaro Watanabe

PRODUCTION Mina Kinukawa, set/projections; Soojin Lee, costumes; Guido Girardi, lights; Dave Iwataki, sound; Ondina V. Dominguez, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere