JUNE 2008

Click title to jump to review

ADAM BAUM AND THE JEW MOVIE by Daniel Goldfarb | Hayworth Theatre

ALEXANDROS by Melinda Lopez | Laguna Playhouse

IMAGINE by Doug Cooney | South Coast Repertory

SOMEDAY by Julie Marie Myatt | Cornerstone Theatre Company

Gut punch

Hollywood provides the setting and the marquee value for the first L.A. staging of Daniel Goldfarb’s ‘Adam Baum and the Jew Movie’ (The Hayworth Theatre, through July 20). Director Paul Mazursky, whose famous films range from the broad-stroke comedy of ‘Down and Out in Beverly Hills’ and ‘Moon Over Parador’ to the detailed portraits in ‘An Unmarried Woman’ and ‘Harry and Tonto,’ applies the fine-tip brush to this layered look at how a major studio head in 1946 weighs his conflicted responsibilities to his art, business and society against the well-being of his nuclear and cultural families.

To wrestle those issues through two acts and two hours, Mazursky has two powerful allies working at the top of their individual strengths. Richard Kind, known for the sitcoms ‘Spin City’ and ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm,’ is a revelation as Samuel Baum, a little man with historic opportunities. Kind’s is the rare performance, of both nuance and range, that will withstand repeat viewings. He works his material like a merchant caressing quality fabric, feeling even the subtlest shift from high to low. Complementing him is Hamish Linklater in a role that shows the range of an actor who a year ago was playing Hamlet locally under Daniel Sullivan’s direction. Linklater’s lanky affability moves organically to upright indignation as he feels the calling to stand up for principles – and his paycheck. Gregory Mikurak, as 13-year-old Adam, holds up the shortest leg of the ensemble stool without a drop in the balance.

But it is Kind’s show. He takes a role that an actor with a shorter throw could be happy to have land in a performance like Mel Brooks’ mayor in ‘Blazing Saddles.’ Kind gets all the laughs that lace the script, the kind of wonderful comedy that kept the Catskills Kosher. His Baum pressures a guest to have some nuts, then mutters in response to his selection, “Cashews. Of course. The most expensive.” It’s as funny as if it were from a famous Vaudeville sketch, but instead of coming across as clichéd self-parody, it deepens the character, reminding that men like this, who were key to forging Hollywood, landed in America without property, and lived with a sense that only that membrane of wisdom and chutzpah kept poverty from reclaiming them.

That fear propels Baum. The play is set in June 1946, a year after the Nazi surrender and full disclosure of the horrors of the extermination camps, and a few months from the conclusion of the first, war-criminal phase of the Nuremberg Trials. However, despite these revelations, widespread anti-Semitism continues to be embraced by too many Americans, with most of the rest in comfortable denial.

The irony, not lost on Goldfarb, is that Jewish studio heads had at their hands the power to influence public opinion through movies, which just had been shown to be effective to the opposite ends by Leni Riefenstahl. So, when ‘Soil in Utopia,’ a book about a Jewish family’s abuse by American anti-Semites, is published, Baum instinctively options it and sets out to have it adapted for the screen. After two writers fail to satisfy him (a loose thread in Goldfarb’s story that needs more clarity), he hires a Gentile, Garfield Hampson Jr. (Linklater). When the story begins, the two are having a story conference after Baum has gone over Hampson’s draft. As Baum systematically demands alterations that pander to the comfort zone of the mass – Gentile – market, Kind makes sure his character’s back pedaling is as funny as it is worrying.

Goldfarb has chosen 1946 for a very good reason. In addition to coming on the heels of WWII, it was the year that Hollywood did, if gingerly, tackle this subject. Two real films were in production at the time the fictitious ‘Soil in Utopia’ was being prepared. Dore Shary’s ‘Crossfire,’ which would be released in mid-1947, and Darryl F. Zanuck’s ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement,’ which would come out a few months later. The first would receive five 1948 Academy Award nominations, but ‘Agreement’ would win three of its five nominations. While ‘Crossfire’ is not referenced, ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement,’ adapted by Moss Hart and directed by Elia Kazan, plays a spoiler role as Baum presses Hampson for changes in time to beat the other film to market.

When he learns of the other film’s plot – in which the main character, played by Gregory Peck, is a Gentile reporter posing as Jewish to experience Anti-Semitism first hand (which will later work for racism in John Howard Griffin’s ‘Black Like Me’ and, less convincingly for sexism in Pollack’s ‘Tootsie’) – he hails it as a brilliant way to wrap a pointed message in kid gloves.

But Hampson insists that they have greater responsibilities: the least of which is being true to the book; the more important of which is to be true to the truth. The debate, which is heated, will end, not by force of intellect or persuasion, but when the person in power applies the anti-Semite label to his hired hand and dismisses him.

All this is played out against a backdrop of young Adam’s Bar Mitzvah. The love and insulation Baum wraps around his son opens the plays counter-balancing dimension. Baum's motivations of entrenchment are complex. So as his devotion to family and faith dictate that he soften his message, he remains unconvinced of his role in the larger battle to make the world a better place for his son, not to mention extending that fight to push for better depictions of other American minorities, who the wise Goldfarb has included in references to the racist co-opting of Al Jolson in black face and Westerns in which Native Americans are played by non-Indians like young Adam.)

To Hampson’s point, real life producers 45-years after the play is set (and a half-decade before it was written) continued to bemoan the lack of progress. In a 1992 interview promoting a new film about anti-Semitism in 1950s America, Sherry Lansing told 'The New York Times’‘ Bernard Weinraub, “Any time you don’t have a movie with Arnold Schwarzenegger in the lead or car chases and explosions, it’s hard to get made. When you have a movie about anti-Semitism in the ‘50s, it’s even harder. Studios don’t think there’s an audience for it. It took us nine years.”

Fortunately, the torch Hampson sought to carry was picked up by Goldfarb, and The Hayworth Theatre has mounted it with high visibility. The brilliance of Mazursky, Kind and Linklater make it shine brightly.

top of page

ADAM BAUM AND THE JEW MOVIE

by DANIEL GOLDFARB

directed by PAUL MAZURSKY

THE HAYWORTH THEATRE

June 6-July 20, 2008

Opened, rev’d 6/6

CAST Richard Kind, Hamish Linklater, Gregory Mikurak

PRODUCTION Joel Daavid, production design; Traci McWain, costumes; Christopher Game, sound; Jennifer Kimpfbeck, stage management; Produced by Gary Blumsack and Danna Hyams

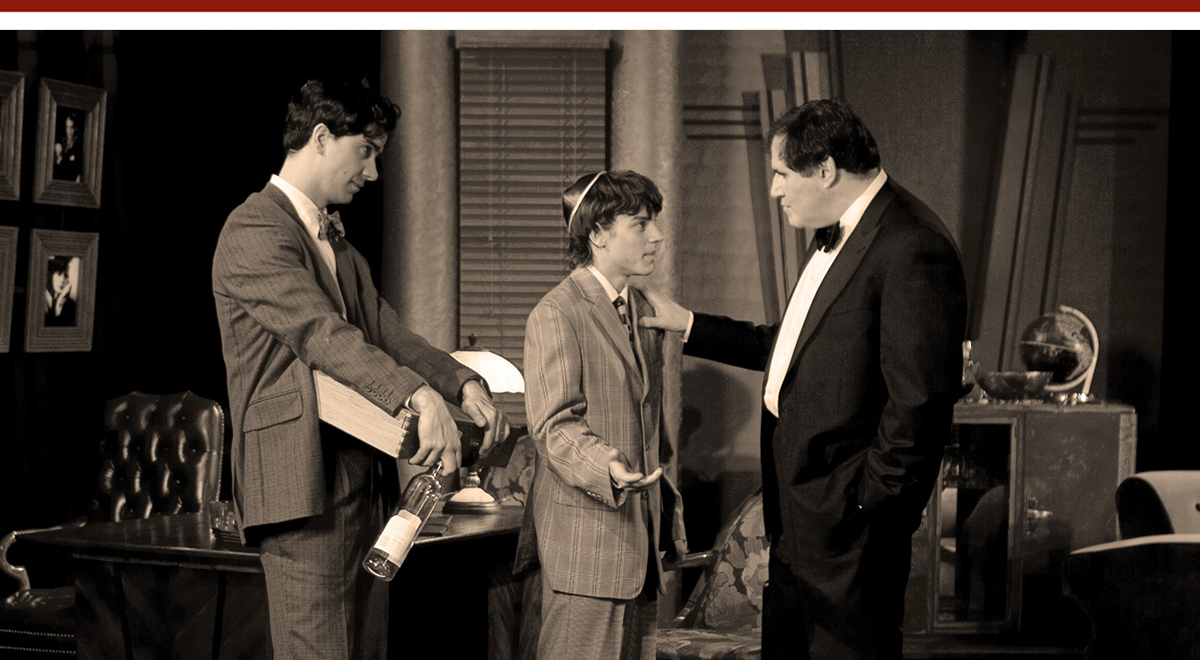

Hamish Linklater, Gregory Mikurak and Richard Kind

Zach Lipp

Unclear family

It takes some time to determine where Melinda Lopez is going in ‘Alexandros,’ the second of her Cuba-America bridge plays to play at the commissioning Laguna Playhouse (through June 29). Unfortunately, once we’re at our destination, even with a ‘come out, come out’ subplot that’s easier said in 2008 than done in the play’s Watergate-era setting, the package feels dull on arrival. Getting there, clearly intended to be more than half the fun, is an uneven ramble of farce, superficial character study, and stock characters. There’s the forgetful grandma, the extroverted but self-obsessed party-mom, and the quiet piano-student teen who harbors insights capable of unlocking the full potential of her older, inauthentic kin.

Lopez challenges director David Ellenstein to balance the serious messages of living honestly (which we ignore, as the excerpted resignation speech of President Nixon attests, at our peril) and the wacky doings of the oddly constructed characters. He achieves only mixed success. The best realized performance is that of Chaz Meña, vaguely invocative of some Andy Garcia - Ron Silver hybrid (not that weird a description when you consider this Latino has starred as Tevya). Whether he’s running around like a lost Marx brother or sincerely peeking out the closet door, Meña is not only believable but likable.

His scenes with Kevin Symons, who also rises above the material, are always engaging, which begs the question of why it is the men who fare better in a story largely about women by a woman. It may be that she has written them more simply, and objectively. The real women who Lopez has grown up with, and who are inescapably sources for her work, may present more important characteristics to wrestle into the work. The men are more simply drawn, and colored with more empathy.

The story centers around a reunion of sorts for a shrinking family of Cuban émigrés. (The play title is the family dog’s name, and points to the Greek showbiz persona one character adopted to hide his true ethnicity.) There are: Abuela (Maria Cellario), the forgetful grand dame whose memory is a convenience store for plot and playwright; her son, Tio (Meña); her daughter, Maritza (Saundra Santiago); and her granddaughter Marty (Katharine Luckenbill). Marty, named after Radio Marti, will honor her namesake as the play’s voice of freedom. The fifth wheel is Eric (Kevin Symons), the extra-familial and overly familiar gardener, whose only possible landscaping talent is back-hoeing.

Despite the appeal of the clarity given the male lovers’ story, it’s Lopez’ three generations of women who demand our attention. In the center is Maritza. The first question is, can her ten-year absence from her declining mother be excused, when it was only the distance between Texas and Florida separating them? As NASA’s Lisa Nowak proved, if you care enough, you can make that drive in no time.

Probably, because it was necessary for Marty to have become mature enough to make her assessments of the others as a semi-equal without them all being so inside each others’ lives so that there was no need for disclosures and revelations. But, for the plot to work, the logic of this family doesn’t. Not without there being some exculpatory dialogue. That would also be useful to make Maritza more likeable, especially challenging after we’ve come to realize that the only reason she has returned: she’s down to her last $4000 after the wheels have come off her second marriage. Her relationships with husbands, daughter, mother and brother are unclear, and it’s hard to keep sluicing through dialogue to mine greater definition when we have a demented grandma with psychic powers and her cruise entertainer son with the faux-gardener boyfriend making sure we don’t take things too seriously.

All these sins are forgivable if the comedy works. But on a set that often seems too big, with an emotional range in Luckenbill’s pivotal performance that seems too narrow, it mostly does not. Luckenbill needs to find a way to play glum and still invite us in.

One of the funniest bits, when characters communicate through a patio door using sign language to avoid detection, really works, and shows both the comedy and subtext about the silliness of deception. However, given the too-small door they must play through, it may be a directorial flourish that came after design meetings would have allowed Marty Burnett to opt for a wider door that would really let us enjoy it more.

Still, the message is a good one: Don’t hold back your true feelings. Be honest, forthright and don’t worry about what the others in the family are going to think. So, we have written our feelings in kind.

top of page

ALEXANDROS

by MELINDA LOPEZ

directed by DAVID ELLERSTEIN

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

June 6-July 20, 2008

Opened 6/6, rev’d 6/7

CAST Saundra Santiago, Katharine Luckinbill, Maria Cellario, Chaz Mena, Kevin Symons

PRODUCTION Marty Burnett, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Paulie Jenkins, lights; David Edwards, sound; Rebecca Michelle Green/Jennifer Ellen Butler, stage management

HISTORY Commissioned by Laguna Playhouse

Maria Cellario, Chaz Mena, Saundra Santiago and Katharine Luckinbill

Ed Krieger

Lines are drawn

The benefits of imagination to help kids escape from and eventually integrate into groups of others is the surprisingly broad sweep of messaging in Doug Cooney and David O’s kid-courting Imagine. The hour-plus play-with-music is now getting its world premiere, under Stefan Novinski’s colorful direction, at the commissioning South Coast Repertory as part of its Theatre for Young Audiences series.

A cast of six, all with plenty to do, drives the 11-song show, effortlessly moving in and out of O’s engaging tunes drawn in the comfort zones of familiar pop and show tune structure. The story, too, begins with a general sense of familiarity – exacerbated by the oddly unimaginative title. But Imagine shakes loose those expectations and we move into a game of “who imagined whom?” that echoes the fun of those attention-demanding time-travel plots.

Sam (James Michael Lambert) lives at the fringes of playground society. No real reason, but he does exhibit some signs of early onset dementia when loose lips telegraph his interior dialogues with longtime imaginary friend "T-Rex" (Brett Ryback). T-Rex, christened during Sam’s critical dinosaur phase five years earlier, is a fun-loving playmate any child would cherish. But, now bordering on adolescence, Sam may be well served to trade him in for something in the real world. His loss will be Rachel’s (Dawn-Lyen Gardner) gain.

Rachel is another schoolyard loner saddled with an even sadder situation. As her sandwich will tell you, she has no imagination. The wise Little Debbie (Jamey Hood), an enchantress in a frock off the rack at Sunnybrook Farm, helps T-Rex, Sam and Rachel in and out of the unseen world of their imaginations. While traveling along, they’ll be both entertained and tormented by Tullabelle (Meaghan Boeing) and Lullabelle (Diana Burbano), two costume-loving teases who just want to have fun.

But there are twists, and an ultimate message that as essential as imagination is to building character, it needs to be put to constructive use, and socializing is an important one. Novinski keeps things humming and he is well served by this fine, and energetic cast.

As is essential with young audiences – and this is really for children as opposed to the once-dreamed of young teen audience – the physical production needs to be fun, and Donna Marquet and Angela Balogh Calin have teamed for a design worthy of the play’s title. They are given full support by the props and production department who lavish loving detail on pieces like a box of singing crayons, a full size paper plane, and the fantasy costumes. Hood’s crayon persona, "Shadow," is the most fun. Cooney uses the crayon world to full advantage, hinting that "Shadow" is, like Sam and Rachel, not the sharpest Crayola in the carton. Though, he does remind us that sharpness in a crayon is actually a negative, indicating non-use. And, the goofy Hood does allow us to feel the waxy complexion of inferiority. After all, she can only offer shades of gray to a world where kids want color. But, any artist knows its shadowing that adds dimension, and Hood certainly supplies Shadow with that.

And, speaking of artists, commendations for pouring time and talent into a playbill of exceptional quality. The full-color handout is chocked full of background and games for the young audience. One can imagine becoming caught up in its imaginative world during intermission and forgetting to get back into Imagine.

top of page

IMAGINE

by DOUG COONEY

music by DAVID O

directed by STEFAN NOVINSKI

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

May 30 – June 15, 2008

(Opened, rev’d 6/7am)

CAST Meghan Boeing, Diana Burbano, Dawn-Lyen Gardner, Jamey Hood, James Michael Lambert, Brett Ryback

PRODUCTION Donna Marquet, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes; Tom Ruzika, lights; Drew Dalzell, sound; Deborah Wicks La Puma, music direction/arrangements; Sara Wilbur, choreography; Kathryn Davies, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Jamey Hood

Henry DiRocco

Rights to bear

For the second installment of its two-year, five-play ‘Justice Cycle,’ L.A.’s Cornerstone Theater Company has premiered Julie Marie Myatt’s Someday (Bootleg Theatre, through June 22), a sensitive reminder of the breadth and diversity of those who desperately want to have a child but can’t, balanced, without irony, by a grateful chorus of would-be mothers who exercised their right to stop having one.

Theatricalizing America’s most divisive issue might be expected to draw on angry polemics and images outside courthouses and clinics. But Myatt, with staging of equal sensitivity from Artistic Director Michael John Garcés, turns her back on the shorthand of placards and protests that too often characterize the debate. She tells her story by letting women speak from their hearts. If there is any protest in Someday, it’s against the random injustices of natural law.

Before the house opens, the Bootleg’s comfortable café lobby is filled with the familiar sound of pop oldies. But these songs - "My Girl," "Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys," "Little Creatures" – are played for a reason. They underscore how ingrained and taken for granted the concept and terminology of parenting is. Someday soon will tell a different story. For barren and same-sex couples, those with disabilities warned against passing their hardship on to a child, and that army of invisibles among us whom the fates have set to navigate life without partners, having a baby may only be possible after extraordinary effort, patience and expense. And adopting a child has become a bureacratic steeple chase only slightly less costly and invasive.

In Someday, Myatt manages to reference all these people by building her play along two narrative lines: Sam and Anne (Shishir Kurup and Bahni Turpin) are a married couple beginning to work with a fertility clinic after failing to have a child on their own; and Ruth (Diana Elizabeth Jordan) is a woman living with cerebral palsy who has her resignation to a life without child exploded when she picks up and caresses an abandoned newborn she finds near UCLA. After attempting to have the foundling assigned back to her by the authorities, Ruth makes her way to the same clinic.

The nexus of these stories is the fertility clinic of the “Doctor,” played by the wonderful Peter Howard. With the whimsy of an escapee from "Scrubs," Howard’s frequently distracted Samaritan allows the show to begin with engaging broad humor before settling down for the serious business. It’s risky, and borderline, but he and Garcés make it work. Over the course of the intermissionless, 105-minute play, he, Sam, Anne and Ruth will cross paths with Gay and Lesbian couples, surrogates, nurses, and mothers who tell their piece of the complicated puzzle of parenting.

The raw emotion and inescapable logic of terminating a pregancy brought on by violence, ignorance or error, come in the form of anonymous thank-you letters from women supported by the Women’s Reproductive Rights Assistance Project. These provide context for each decision along with the appreciation. Myatt and Garcés draw the women’s stories into the play by having the actress, after she recites the letter, hand a copy to an audience member.

The space created by Lynn Jeffries is an essential and complementary part of the experience, promoting Cornerstone’s emphasis on communal involvement. At rise, the large cast floods the stage as pedestrians, many with babes in arms. The 25-member cast fills the playing area that cuts diagonally through the rented Bootleg Theatre’s roomy black box. Between banks of seats, they tred a painted mosaic of various shades of blue. It could be the linoleum floor of the hospitals and homes within the story, or the sun-dappled river that might flow through each of us, from our parents to our children and beyond. Its reach into past and future is nicely represented as it splashes up the curtains at either end of the set.

Those who’ve worked in venues with in-the-round or full-thrust stages know the experience of watching audience members through the action. Too often, the effect is dampening as our attention is drawn to someone slumbering. It’s unlikely such configurations could ever work better than here, where the embrace of audience on both sides of the actors means we see the reflection of our own engagement. This is most evident in the scene between Ruth and her boss, played by Loraine Shields.

And that brings us to Ms. Jordan. As Myatt showed in last year’s My Wandering Boy [REVIEW], which touched a deeper chord in this reviewer than others, this young writer has a gift for letting us hear the unspoken and feel the ache of absence. Emptiness is an elusive emotion to depict onstage. But the way it is embodied by Ms. Jordan, without self-pity but nobility, is something that helps touch a fine production with the miraculous.

There is in her scenes, particularly those with Tracey Leigh Turner, as much bravery onstage as there must be in the real lives of those who own these stories. If Jordan takes her performance to the wall every night of the run the way she did on opening night, she may not see an Ovation Award, but, selflessly, she will have left everyone who saw her with a more timeless gift. And, she, Myatt, Garces and the Cornerstone company, will have given those in L.A.'s theater community a greater pride in the potential of this crazy business.

top of page

SOMEDAY

by JULIE MARIE MYATT

directed by MICHAEL JOHN GARCES

CORNERSTONE THEATER COMPANY

May 29-June 22, 2008

(Opened, rev’d 6/6)

CAST Diana Elizabeth Jordan, Bahni Turpin, Peter Howard, Shishir Kurup, Joshua Lamont, Gabriel Rodriguez, Jay Charan, Belinda Arredondo, Tracey Leigh Turner, Alicia Tao, Neetu S. Badhan, Saima Husain, Bonnie Brennan, Jamy Myatt, Tracey Silver, Kozetta Garnett, Serena W. Lin, Sabrina Sikes, Ramy Eletreby, Jeremiah Ocañas, Loraine Shields, Alison Regan, Mark Strunin, Blanca Gutierrez, Juanita Chase

PRODUCTION Lynn Jeffries, set; Meghan E. Healey, costumes; Dan Jenkins, lights; John Nobori, sound; Terri Roberts, stage management. Jon Neustadter/Stuart & Susie Berton, producers

HISTORY World Premiere