MARCH 2007

Click title to jump to review

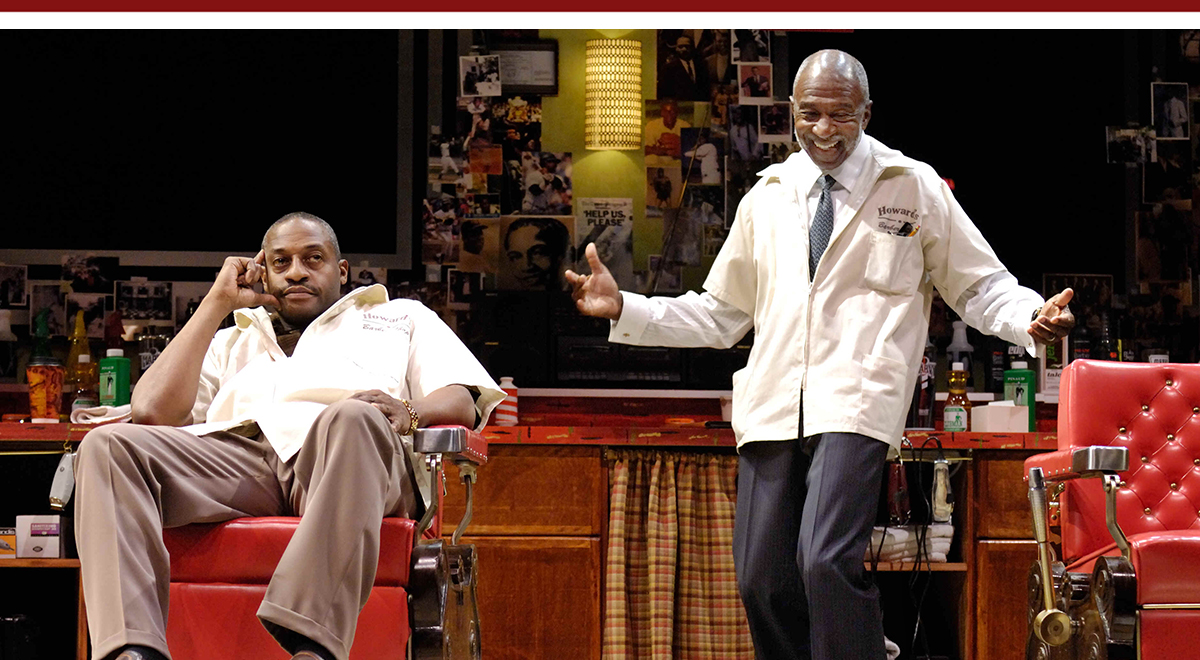

CUTTIN' UP by Charles Randolph-Wright | Pasadena Playhouse

DISTRACTED by Lisa Loomer | Mark Taper Forum

MACBETH by William Shakespeare | Open Fist Theatre

THE PIANO TEACHER by Julia Cho | South Coast Repertory

RESTORATION COMEDY by Amy Freed | The Old Globe

TWELVE ANGRY MEN by Reginald Rose | Ahmanson Theatre

Literary salon

The name of Charles Randolph-Wright’s new play, at the Pasadena Playhouse through April 15, is inherited from its source material, Craig Marberry’s book of first-person stories about the role of barber shops, barbers and even hairstyles in Black America. While the punny Cuttin’ Up sounds ominously jokey and shallow, both book and play are in fact collections of life experience that often achieve a kind of folk wisdom. By turning Marberry's real people into stage characters, Randolph-Wright ironically has made them come to life in a way that offers even greater insight with the entertainment.

Randolph-Wright, who wrote Blue, seen on this stage some years back, and Marberry both believe that, as one character says, "More black history is taught in a barbershop than in school." And they make a good case for the assertion. Prospective "students" will be relieved to learn that this lesson plan rarely becomes a lecture. Instead, the instruction is through the stories average men and women tell each other, passing vital oral history as they simply pass the time.

Israel Hicks’ direction of a cast without a weak link gives Wright all the dimension he could ask for. A realistic and lovingly detailed set by Michael Carnahan and a parade of costumes by David Kay Mickelsen are warmly lighted by Phil Monat's design.

There are three chairs in Howard’s Barber Shop, an institution with 50 years of service to its African American clientele. The men behind those chairs, who are Randolph-Wright’s invention, are, from left to right and youngest to oldest, Rudy (Dorian Logan), Andre (Darryl Alan Reed) and owner Howard (Adolphus Ward). Rudy is young and playing the field in more ways than one. Romantically, religiously, musically and career-wise, he is using his youth as a time to dabble and learn. Howard is as bolted to his family, profession and beliefs as his swiveling barber chair is to the linoleum and concrete. As lean and tough as his leather strop, he wears a half-century of listening as loosely as his barber's smock, saving his hard-won opinions until a time they might be heard.

At the middle chair, the middle age and the mid-life crisis is Andre, a man who despite several marriages has kept himself unattached, moving from city to city and shop to shop. Born into the trade, which he began as a boy, his skill has allowed him to escape one tangle after another, making him a true journeyman barber. Andre's story becomes the arc upon which the other stories hang. However, to keep the balance right, Randolph-Wright correctly avoids delving too deeply into his psychology. He's here for plot motion, not for psychoanalysis. For his part, Reed keeps this relationship in check, not drawing any more focus than anyone else in this finely tuned ensemble.

The actors who each create what seems like a half-dozen people, are Harvy Blanks, Bill Grimmette, Iona Morris, Maceo Oliver and Jacques C. Smith. Each must perform a feat of personality double-jointedness to make these various habitués of the hair salon unique. Surely, however, the fellows would tip their hats and hairpieces to Ms. Morris for her work here. She is the key player outside the three barbers as she alone provides the woman’s touch for love interests, mothering, sirens' calls, etc. (And she did it all while producing and directing a local awards show that took place days after opening.)

In Cuttin’ Up, the barbershop is the community's counterbalance to church, a secular social club where the music of Pendergrass, the Spinners and the O'Jays are among the songs of praise. Each barber embraces the music of his era – from jazz to R&B to hip hop – providing a nice motif for each generation's conflicting passions.

As a balance of theater entertainment and useful truths, Cuttin’ Up is both boulevard and street. The mix over the 2 hours and 15 minutes feels just right. The numerous stories sometimes relate to the barbers but more often are recollections from their past, digressing even intol stories within stories. All celebrate these just plain folk in uniquely American tales of survival. Mandatory attendance at Cuttin’ Up would be an appropriate LAUSD appropriation . . . if it didn't feel like cutting class.

top of page

CUTTIN' UP

by CHARLES RANDOLPH-WRIGHT

based on the book by

CRAIG MARBERRY

directed by ISRAEL HICKS

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

March 9-April 15, 2007

CAST Harvy Blanks, Bill Grimmette, Dorian Logan, Iona Morris, Maceo Oliver, Darryl Alan Reed, Jacques C. Smith, Adolphus Ward

PRODUCTION Michael Carnahan, set; David Kay Mickelsen, costumes; Phil Monat, lights; James C. Swonger, sound; Jill Gold/Lea Chazin, stage management

Darryl Alan Reed and Adolphus Ward

Craig Schwartz

Attention must be paid

The physical production of the Mark Taper Forum premiere (through April 29) of Distracted, Lisa Loomer’s comedy about contemporary parenting woes, seems to be trying to get the script’s attention. Elaine J. McCarthy’s set, a kind of pop-up-greeting-card with diamond vision, screens a furious pre-show montage of media images that accelerate, crescendo and stop for the play to begin. It suggests that 9-year-old Jesse’s meltdowns may be partly caused by our daily bombardment of sensory stimulation. Certainly his parents have problems communicating between the distractions of incoming calls, digital programming and other modern conveniences.

But here in Los Angeles, a.k.a. television city, that "media is the menace" message goes in one earphone and out the other. Despite a stage festooned with cell phones, remotes, Blackberrys, video game controls, big screens and the like, media overload is not among the suspects fingered by Distracted. Instead, the latest effort from the author of The Waiting Room makes its case against genetics, diet, chemical imbalance and parental inattention. And, in the script's defense, it does provide two entertaining hours of distraction. Even if, wanting to be both "SNL" and "Frontline," it exhibits a little bi-polarity of its own.

This is the third issue-oriented comedy with a central female character from Ms. Loomer. She began with Expecting Isabel (about having a baby), followed with Living Out (about having a caregiver), and now offers this play about having a hyper-negative child. After too many calls from teachers at wit's end, and too many days that feel endless, Jesse's mother, played by Rita Wilson, is compelled to have the child tested. She learns that what's behind her son's mood swings, which register their narrow arc on the Don Rickles-Lenny Bruce Scale, is Attention Deficit Disorder, or ADD. If that sounds too syndrome-specific, Ms Loomer is just using it to get at a more basic parental conundrum: how to balance a child’s need for self- expression and growth with the discipline needed to keep him from becoming a self-centered ass.

For those interested in dissecting the clinical side of Distracted, the program offers an excerpt from The Last Normal Child by Dr. Lawrence Diller. (It, and a great study guide, can be accessed here.) What’s coming off the stage, however, may do greater good as a diversion than as dissection.

In this slick staging by Leonard Foglia, back at the Taper after his hugely successful turn introducing McNally’s Master Class, the first asset is its cast, lead by Ms. Wilson. As our genial guide down the rabbit hole of guilt and confusion, Ms. Wilson is always on stage. She keeps her character engagingly funny, always real and always watchable. While she has to be the punch line for a series of goofy specialists, then punching-bag to her humorless husband (played by Ray Porter), she also has to stand and deliver her own one-liners. She performs all these operations seamlessly.

For his part, Porter must portray the spouse who refuses to buy into anything his better half attempts. His is a kind of knee-jerk anti-authority stance that leaves him too much jerk and too little kind. Given that, it's ironic that he is vindicated when, to an inverted hip-hop take on Tom Hanks' keyboard dance in Big, Jesse's turnaround shows Dad's foot-dragging to be what protected his son's integrity. (If he'd only been there for Randall P. McMurphy and Elwood P. Dowd.)

Bronson Pinchot and Stephanie Berry stand out as they run characterization marathons of four or five identities each, with a Berry quick-change that would confound Copperfield. Those multiple assignments however leave Marisa Geraghty and Johanna Day with little to do as neighbors. Day nevertheless manages to shows her acting chops in tiny scenes as an obsessive-compulsive busybody, eliciting congratulatory applause on each of the first three of her four or five exits. Hudson Thames provides the major minor role, with Emma Hunton sympathetic as a troubled teen.

Another asset is McCarthy’s cinematic slide show, which beyond its pre-show and intermission duties reminding us of how intrusive media has become, provides evocative still-photo backdrops. One close-up of a chipped dinner plate, snug in its stack, presages the play’s ultimate message of acceptance.

And finally, Loomer and Foglia have threaded the show with a healthy dose of irreverence for theater convention. Character-dropping asides that blur the actor-role divide further the effort to decriminalize ADD. It’s a reminder that this Public Service Announcement about Attention Deficit Disorder is brought to you by People Who Have It.

All in all, it’s a fun night of well-produced theater that cautions not to be too quick to medicate those quarrelsome kids. Its message for parents is tolerance. The best hedge against our children getting Attention Deficient Disorder, Ms. Loomer feels, simply may be “paying more attention to our children.” Of course, those whose post-show calm will be broken upon the threshold of their own homes, where their children lie ready to disobey any logical suggestion, may join the set in offering a second opinion about the play's tidy conclusion.

top of page

DISTRACTED

by LISA LOOMER

directed by LEONARD FOGLIA

MARK TAPER FORUM

March 15-April 29, 2007

(Opened 3/25)

CAST Stephanie Berry, Johanna Day, Marita Geraghty, Emma Hunton, Bronson Pinchot, Ray Porter, Hudson Thames, Rita Wilson

PRODUCTION Elaine J. McCarthy, set/projections; Robert Blackman, costumes; Russell H. Champa, lights; Jon Gottlieb, sound; David S. Franklin/Michelle Blair, stage management

HISTORY World premiere.

Ray Porter, Bronson Pinchot, Rita Wilson

Craig Schwartz

A western bard

The Open Fist Theatre Company on Santa Monica has mounted a handsome production of Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth,’ under the direction of Arne Zaslove. Costumer A. Jeffrey Schoenberg’s detailed duds visually move the company of characters from Scotland to the American Old West. There's a real temptation to check the alley behind the theater for hitching posts and corrals.

However, while the conceit provides welcome justification for the use of American accents and acting instincts, whatever insights the play's transposition intends for its new setting, or expects the setting to shed on the play, are hard to assay. Nevertheless, the relationship at the core of the play, is given some color here that, while not necessarily a product of the updating, does give the show new heart.

This adaptation in fact is only skin deep. The text has not been altered – as best I could fathom – beyond directional references like Malcolm's and Donalbain's flights now being to 'north' and 'west' rather than England and Ireland (should that be 'south' and 'west?'). So Macbeth here remains a world of armies, kings, reigns and realms, lieges and heaths. With few exceptions, the costumes portray all the men as cowboys of equal stature. The wounded sergeant who helps get things started is not wearing a recognizable army uniform to provide historical coordinates. We don’t get a sense that there is any reason why we're in the Old West. Are these cattlemen, railroad barons, bankers, lawmen, Mexicans, politicians, traders, trappers, outlaws, prospectors? There were certainly plenty of people out to consolidate power in those days. We can only infer what Mr. Zaslove's reason for putting them here is.

In fact, the strength may not be in making parallels to the Old West and its historical figures. Here, we do get a powerful dynamic between Macbeth (a solid Adrian Sparks) and Lady Macbeth (Lisa Glass). Their mutual hunger for advancement does not seem to be about political or financial power, but by the need for Macbeth to be more of a man in his wife's eyes. Mr. Sparks and Ms. Glass make this a very physical connection. Macbeth's desire for advancement is about proving himself worthy. Of course that gets lost in the expanding net of deceit and murder that follows. But as an impulse to get things started, it's interesting and insightful. For her part, the husky-voiced Ms. Glass gives her Lady an earthiness that fits the time and place Mr. Zaslove has chosen and her nightmare scene is particularly affecting.

The actresses who play the witches are also double-cast into the Macbeth household, providing some eerie potential for the sage women to be either Mexican or Indian maidens who, though subservient domestically carry powerful magic from the other world that they bring to bear. However, Mr. Zaslove's documented fondness for mask use, though used sparingly, still shows the weakness of this theatrical tool as it makes the actresses facially one-dimensional (as it muffles their voices somewhat).

Without directorial choices and visual aids to provide stirrups for Mr. Sparks to sink his feet in, his ride on this handsome beast can seem at times to bounce around. As a result, he goes for the big payoff on a lot of the speeches and they begin to sound the same after awhile. Mr. Sparks is clearly a capable actor, so it's far from the worst complaint to note he seems obliged to give too much. This Macbeth is looking for his turf. Without that sense of grounding, he really is at the whim of the fates.

Many 19th Century American men amassed enormous wealth and power in the West. Actors and audiences both likely rode to the performance on surface streets that recall these past or present members of the California aristocracy: from Sepulveda and Pico to Chandler, Mulholland and Huntington. Whether there are parallels in Mr. Zaslove's interpretation or not may best be sorted out in discussions while driving those mean streets home.

top of page

MACBETH

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by ARNE ZASLOVE

OPEN FIST THEATRE

February 16-April 7, 2007

(Opened February 23)

CAST Colin Campbell, Bruce A. Dickinson, Frankie Foti, John Gegenhuber, Lisa Glass, Ethan Hova, Joe Hulser, Bill Jackson, Bjørn Johnson (replaced by Aaron Hendry at this performance), Conor Lane, Lawrence Lowe, Maia Madison, Andrew Schlessinger, Owen Sholar, Adrian Sparks, Ann Stocking, Teresa Willis

PRODUCTION Meghan Rogers, set; A. Jeffrey Schoenberg, costumes; Cricket Sloat, lights; Tim Labor, music/sound; Allison Smith, stage management; Martha Demson, producer

Adrian Sparks

Practiced composure

Survivors of atrocities – from wholesale genocide in Germany, Cambodia or Rwanda to molestation and domestic violence at home – carry that evil for the rest of their lives. In Julia Cho’s superbly crafted The Piano Teacher, premiering through April 1 at South Coast Repertory, the playwright provides sympathetic study of the effects of living in denial of these experiences, letting oneself be innocently pulled into their currents, or seeking haven behind their disguise as "just stories."

In Kate Whoriskey’s pitch-perfect staging, The Piano Teacher further cautions that children – whom Cho describes as "pure imagination walking around in skin" – are as susceptible to the poisonous effects of horrific stories as they are to the lingering effects of secondhand smoke. Most importantly, however, she demonstrates that great storytelling continues to find its true haven in the world of theater.

To usher us through this rewarding and riveting experience, Ms. Cho has created a harmless retired piano teacher named Mrs. K (Linda Gehringer, making the most of a golden opportunity to define a complex new addition to theater literature). Mrs. K is a kind, cookie-nibbling neighbor lady “many years” into widowhood. From the arpeggio door chimes to the wedding ring she still wears, she appears cheerfully resigned to her solitude, warm beneath a comforter of memories from her years helping children discover music. From her dilapidated armchair, she tells mundane recollections from a quite forgettable life, winning our hearts with the kind of simplicity Wallace Shawn’s Lemon begins the more controversial but similarly woven Aunt Dan and Lemon.

In the process of sharing with the audience some souvenirs of those happy days she finds the address book she used to track her students’ progress. Its scented reward stickers activate images of those tiny faces and she decides to call some decades-old phone numbers in the slim hope of catching up with some former pupils. She eventually will reunite with two of them: Mary and Michael (Toi Perkins and Kevin Carroll, providing haunting interpretations in their SCR debuts). They will in turn reunite her with aspects of that earlier time that she may or may not have understood.

The storytelling prowess displayed in 'The Piano Teacher' would only be diminished by further specifics. But the multi-layered beauty of the play can be glimpsed in something as deceptively simple as the central character's name. In Mrs. K., Ms. Cho not only suggests the integral role of a Mr. K, she hides any nationality or ethnicity the full name might carry. Unintentionally, but deservedly, she also invokes the eerie worlds of such masters as Kafka, Poe and others who often used a single character to identify their characters.

For her part, designer Myung Hee Cho takes what might have been constraints of the production concept and turns them into complementary statements in their own right. Walls that must be left bare for upstage reveals tell of a home without family photos, paintings or bookshelves. It is, in fact, a household turning its back on its history. That same wall, arcing like a concert hall band shell, recalls the world of musical performance. Lighting designer Jason Lyons has created a beautiful palette of cues and specials to articulate the focus and intensify the drama. Stage manager Jamie Tucker calls the shifting illuminations with sly precision. Only a couple of unnecessary sound cues in act one feel out of place, as tiny retreats from confidence in the power of the spoken word to paint a complete world in story.

South Coast Repertory, which launched such current staples of American theater as Donald Margulies' ‘Collected Stories,’ Margaret Edson’s ‘Wit,’ and Richard Greenberg’s ‘Three Days of Rain,’ can add another script to that list. For her part, Ms. Cho has given the American theater new proof of its power and relevance. And as she artfully reminds us that hidden in plain sight are negative forces that must be dealt with, she steps forward as a positive theatrical force we look forward to dealing with often in the years ahead.

top of page

THE PIANO TEACHER

by JULIA CHO

directed by KATE WHORISKEY

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

March 11-April 1, 2007

(Opened 3/16)

CAST Kevin Carroll, Linda Gehringer, Toi Perkins

PRODUCTION Myung Hee Cho, set and costumes; Jason Lyons, lights; Tom Cavnar, sound; Deborah Wicks La Puma, music consultant; Megan Monaghan, dramaturg; Jamie A. Tucker, stage management

HISTORY Commissioned and developed by South Coast Repertory; World premiere.

Linda Gehringer and Toi Perkins

Henry DiRocco

Worthy effort

As her ‘Beard of Avon’ did with the Shakespeare canon in 2001, Amy Freed’s newest play both explores and expands on the literature of classic British theater. Coated in the finery and flippancy of its namesake, 'Restoration Comedy' sets about seducing the old form with lively wordplay as foreplay. Under director John Rando's guiding hand, the current mounting at the Old Globe (through April 8) again reveals Ms. Freed's special gift for linking past and present in affectionate parody that is equal parts love- making and lampooning.

From its deceptive plotlines to its plunging necklines, Restoration Comedy embodies the stay-popping abandon that briefly swelled the English stage in the second half of the 17th Century. The Puritan-scattering return of Charles II in 1660 launched a half-century of change. After attending French theater, where unlike the British stage women’s parts required actors with women’s parts, Charles immediately ordered an end to the playing of female characters by boys. Plays of sexuality, clever plotting and witty dialogue now filled the theaters. Women flourished in all aspects of show business. Playwright Aphra Behn became the first woman writer of any kind to be published in England. Fifty other plays by women were published during the period, surely a mere fraction of the total written and produced. By 1710, the censorious spoilsports had rallied in enough density to demand an end to all the fun. These wet blankets quickly covered cleavage, revoked licentiousness, and damped the flame of artistic freedom. No female British playwright would achieve the success of Susannah Centlivre, whose 1709 'The Busybody' was one of the period’s last hits, until Agatha Christie’s ‘Mousetrap’ more than two centuries later.

Ms. Freed hangs her attachment for the period on two plays: Colley Cibber’s ‘Love’s Last Shift’ and John Vanbrugh’s ‘The Relapse.’ Cibber’s story introduces the adulterous Loveless, who becomes obsessed with his own wife Amanda only after she seduces him pretending to be a prostitute. Vanbrugh set the more cynical (and still produced) ‘Relapse’ to begin at the end of Colley’s tale, where Loveless, more true to the form, can’t resist returning to womanizing and leaves Amanda again. Ms. Freed makes it a trilogy of sorts by incorporating the first two, moving Amanda to the center of the story, giving Loveless a final mistress who is his moral match, and giving Amanda an adoring suitor who is hers. In doing so, the writer keeps the spirit and themes – sexual addiction, the Madonna-prostitute conundrum, marital incompatibility -- of the originals while adding a contemporary sensibility.

As Loveless, the wonderful Marco Barricelli kicks things off by bounding through the fourth wall like a Catskill emcee, introducing himself and his story in rhyming couplets. But Ms. Freed also has the actor inside the character come through: suggesting in asides that the acting company's main interest in the play is getting to wear the lavish costumes. He also promises to drop the antique meter.

Loveless, we learn, has returned from France in need of restocking the finances he’s frittered. He is a man of sufficient appetite for women and wine that he chewed through his marriage tether years ago. From afar he heard that his wife was dead. His wife Amanda (Kozlowski), meanwhile, has been led to believe the same thing about him. Loveless's old friend Worthy (Frechette) has been assuaging his secret love for Amanda by buttering up the empty-headed but dowry-heavy Narcissus (Amelia McClain). When he stumbles upon the just-returned Loveless he quickly hatches a plot. He presents the plan to Loveless as in his best interest, to Amanda as in hers while actually the whole thing is designed to collapse in Worthy’s lap, where he hopes Amanda will opt to stay.

A secondary plot underscores the real dilemma of men born after the eldest son. Only the first-born received inheritance under the structure then. To secure income, the rest married for dowry and not for love. The father and son Fashions (Danny Scheie as Sir Novelty and Michael Izquierdo as his scion) bring in this aspect as they pursue Hoydon (McClain again in double-casting that gets a bit confusing). Sheie has a great comic turn as Ms. Freed's recreation of Lord Foppington, a character who in Vanbrugh's 'Relapse' was first played by Colley Cibber, the writer of the play that started the whole affair.

Barricelli is a must-see for fans of classic theater. His performances, which never overshadow, are powered by a rare quality of both detailed mastery and unbridled brio. In Kozlowski, Ms. Freed has lucked into another rare creature. Amanda has been her role in all of the play's first three productions and it is clear why. She convincingly moves from guarded “widow” to pain-inducing temptress. Mr. Frechette's delightfully idiosyncratic delivery gives him Worthy enough quirk to keep him from being too honorable.

Ralph Funicello’s stage-on-stage set is arguably the most fitting scenic design we've seen in this space. In tone and texture it completes the theater’s interior as sincerely as if he’d repaired a wooden bowl. Upon entering the house, there is a sense that he went back to hundred-year-old blueprints to restore the theater to the original look. Its two portals, with second story landings, bring the curve of house balconies through the proscenium and halfway upstage. Its curtains, combining fabric and painted flat, are drawn – pinned and penned -- open. Under York Kennedy’s pre-show lighting, the simple but evocative stage readies the audience for 'Restoration Comedy's blurring of classic and contemporary periods. Like the baseball fan who arrives before the players take the field, the early arrival to ‘Restoration Comedy’ has a contemporary environment upon which to muse on tradition, certainly as far back as the Restoration.

top of page

RESTORATION COMEDY

by AMY FREED

directed by JOHN RANDO

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

March 8-April 8, 2007

(Opened 3/16)

CAST Marco Barricelli, Chris Bresky, Chip Brookes, Peter Frechette, Cara Greene, Rhett Hinkel, Michael Izquierdo, John Keating, Caralyn Kozlowski, Amelia McClain, Jonathan McMurtry, Aaron Misakian, Danny Scheie, Kimberly Scott, Christa Scott-Reed, Summer Shirey, Kate Turnbull

PRODUCTION Ralph Funicello, set; Robert Blackman, costumes; York Kennedy, lights; Paul Peterson, sound; Michael Roth, music; Diana Moser/Jenny Slattery, stage managementO

HISTORY Commissioned and developed by South Coast Repertory; World premiere.

John Keating, Marco Barricelli, Danny Scheie, Caralyn Kozlowski, and Kimberly Scott

Craig Schwartz

Guilty pleasure

There are bus and truck tours and there are military convoys. While technically the former, the current production of Reginald Rose’s Twelve Angry Men, at L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre, is rolling across America with the invincibility, not to mention temperament, of the latter.

The Roundabout Theatre Company production now parked on Temple Street may be a 50-year-old drama, but thanks to the new engine rebuilt on director Scott Ellis’s fluid blocking, it likely will have the payload of a Brinks truck when it heads out of town on May 6. Ellis directed a different cast in the play’s 2004 Broadway debut at Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre, earning the show critical praise, four Tony nominations and a round trip National Tour ticket that gets punched in Florida after this and again in Southern California next February at Costa Mesa’s Orange County Performing Arts Center.

This deliberation room drama about compassion versus justice did not develop along the usual play-film-television path. Originally a ‘Studio One’ teleplay in 1954, it was adapted to film in 1957, becoming director Sidney Lumet’s first feature. It was also the only producing credit its star, Henry Fonda, would ever have. It became a stage play almost as an afterthought when Rose adapted it in 1964. Yet it did not get to Broadway until the Roundabout staging, which became that company's longest-running hit at 228 performances.

Like Agathe Christie’s And Then There Were None or Peter Greenaway’s Drowning by Numbers there’s a numerical predictability to the plot of Twelve Angry Men that challenges its director and performers. However, unlike those – and most other – crime stories, the sleuths here are laymen locked in a room with only their notes, their memories and their prejudices to see them through.

The play opens in the empty Jury Room #2 of Allen Moyer's time-capsule set. We hear the judge (Robert Prosky, in an audio holdover from Broadway) read the jury instructions: In this case a guilt verdict will carry the death penalty. The jury's decision, guilty or not guilty, must be unanimous. But a guilt verdict must be believed by all 12 to be beyond any reasonable doubt. Even one dissenter will produce a hung jury requiring a retrial.

The 12 men are all white, all middle-aged (except the ancient Juror #9, played by Alan Mandell), and all gainfully employed (again with the exception of the retired #9). They begin with a general assumption that they lean equally toward a guilty verdict. Eleven of them do. Only Juror #8 (Richard Thomas) has misgivings about this rush to judgment. Several things trouble him, not the least of which is lock-step with which his fellow jurors are ready to move on with their evenings.

It falls to #8 to have his concerns answered or convince the other 11 of the need for doubt.

What keeps this from being an exercise in ticking off the conversions is, for one, Ellis’s unseen magician’s hand. He keeps the men moving without ever intruding or making their actions seems gratuitous. This is necessitated by the stage being raised and half the cast upstage of a big table and the other half with their backs to the audience. Yet, virtually every comment by a juror propels him up out of his seat, or opens him out to the house without it seeming forced.

Ellis also has a great ally in Thomas, who as Juror #8, must create an emotional arc beyond playing the numbers. He must also prevent his character from becoming unbearably sanctimonious in his role as the conscience of America. He does this by expanding his passion midway to include excitement in his role as detective. This catches fire with the others, allowing them to have new energy for re-examination.

Among the other members of the strong cast, Randle Mell and Julian Gamble are standouts as Thomas’ most entrenched adversaries. Rose has given them Achilles’ heels that could turn them cardboard without the kind of intensity they bring. Gamble, for example, must at one point unleash his inner monster, let it consume all the oxygen in the room, and then quietly work the evil genie back into the bottle. He makes it painfully believable as we see his character in the aftermath, first decompressing, then losing interest.

The issue of race, justice and minority participation in the system are the factors that most show the play's age. One might argue that Rose was not interested in (or compelled to do) more than a story about the danger of single-mindedness. Hence the room full of equals. But, with a defendant who is clearly a teenage member of a minority, this is so not a jury of his peers. Instead it’s a reminder of Americans who were not represented on Juries for a long time. That crime was eventually solved. But it's not what's making these men angry. Still they help raise the issue, if inadvertently. So, sentencing on this tour is commuted.

In 1997, with new questions regarding the meaning of reasonable doubt following by the OJ Simpson trial, Showtime produced a new movie version of Twelve Angry Men directed by William Friedkin and featuring a racially diverse cast.

ON THE REAL SIDE: A TIME Magazine article from 1970 of bias in jury selection.

top of page

TWELVE ANGRY MEN

by REGINALD ROSE

directed by SCOTT ELLIS

AHMANSON THEATRE

March 28-May 6, 2007

(Opened 3/29)

CAST Charles Borland, Todd Cerveris, Scott Cunningham, Julian Gamble, Jeffrey Hayenga, David Lively, Alan Mandell, Randle Mell, Mark Morettini, Patrick New, Jim Saltouros, Richard Thomas, George Wendt

PRODUCTION Allen Moyer, set; Michael Krass, costumes; Paul Palazzo, lights; Brian Ronan, sound; John Gromada, music; Michael McEowen, stage management

HISTORY A Roundabout Theatre Production