MARCH 2008

Click title to jump to review

THE AMERICAN PLAN by Richard Greenberg | The Old Globe

BROWNSTONE by Catherine Butterfield | Laguna Playhouse

CULTURE CLASH IN AMERICCA by Culture Clash | South Coast Repertory

THE DYING GAUL by Craig Lucas | Elephant Theatre

HENRY IV, PT 1 by William Shakespeare | A Noise Within

MASK by Anna Hamilton Phelan, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weill | Pasadena Playhouse

NO CHILD by Nilaja Sun | Kirk Douglas Theatre

SWEENEY TODD THE DEMON BARBER OF FLEET STREET by Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler | Ahmanson Theatre

Heir to the throne

Of Shakespeare’s three major play categories – comedies, tragedies and histories – it’s the chronicling that most needs borrow from the others. It’s Shakespeare’s drama and humor that keeps his recounting of court and battlefield exploits engaging for foreign audiences like us. Henry IV, Pt. 1, kicking off the second half of A Noise Within’s 2007-08 Repertory Season (through May 18), provides his histories with one of theater’s greatest comic creations in Sir John Falstaff. The bloated blowhard, whose famous soliloquies are as insightful as they are entertaining, is here rendered by playhouse co-director Geoff Elliott, who co-directs with Julia Rodriguez Elliott.

Here, the Glendale company mounts another solid production that provides clear access into this classic. It both benefits and suffers from the old rep company tenet of a limited number of actors taking on unlimited roles over time. The grand premise, the bedrock of early British and American theater companies, balances the fun of seeing familiar actors inhabiting unfamiliar roles against the demands of precision casting. We’ll either be fascinated when our friends’ faces become barely recognizable on the fictional bodies, or lose the fictional creations in the folds of individual actor tricks. So it is that most folks within Within’s audience will be sufficiently enthralled by Elliott, and Robertson Dean in the title role. Others, however, may find the play ill-served by the stretch of actors whose elasticity is getting played out.

The bright light in this serviceable production – as it is in the story of Henry’s fight to hold England together – is Harry, the future Henry V. Making his Noise debut is Freddy Douglas. Douglas gives the play guest-artist energy, just as Kirsten Potter’s company debut did for As You Like It two seasons back. Meanwhile, J. Todd Adams, as a buff, fired-up Hotspur smacking of growth hormone abuse, is the squarely structured play’s fourth corner.

Douglas reveals the fine definition of training and apprenticeship in his native England. He has the outstanding enunciation of an O’Toole, yet alternately yields and commands his scenes with his occasionally less interesting scene partners. (He and Adams get the featured spot in the curtain call, but, oddly, not in the press photos.) And, while Falstaff is by far the most interesting character in this play, he is diminished by Elliott’s actorish delivery. Still, when Elliott wants to nail something he pulls in the oars and rests the broad stroking to show what he can do. This is the case with his lovely rendering of the Catechism speech. But much of the broader scenes seem lost, which gives Douglas (and, briefly, Jill Hill’s Mistress Quickley) less to play against.

On the other end, the real Henry IV’s reputation for careful contemplation and strategizing turns, like milk, in Dean’s interpretation, to somber and internalizing. While Elliott’s Falstaff seldom finds real footing, Dean’s Henry doesn’t gain traction. Adams, despite a couple of moments in which he pushes over the top, seems to be overcompensating for these others. Still, he remains on target and, with Douglas, perform Ken Merckx’ stage choreographer like they mean it. Their hand-to-hand combat is tight, dangerous, and energized. When the full battle arrives to end the play, the combat spills up the aisles yet keeps its intensity. (Ms. Rodriguez Elliott, who often takes choreography chores at the theater, may be due some of the credit here.)

Of the others, Steve Weingartner shows himself, as he did with Calaban a couple years back, a great if quiet asset to the company. In his key and minor roles, he finds his spots in the storytelling and owns them with just the right amount of flavor and command. The women, true window-dressing in this story, are all solid: Hill, always fun to watch, Dorothea Harahan, and young Jessica Berwin, following up her lovely Dear Brutus appearance, does well in her non-English-speaking speaking role.

Ultimately the Elliotts have put up a Henry IV that offers clarity if not a combustion. Merckx has done great work here and Soojin Lee adds to her impressive list (though the fat suit is a bit lumpy). And, while we hope to see Douglas as a regular here, we urge casting directors at the other Southern California regionals to give him a real test drive in one of their marque productions

top of page

HENRY IV, PART 1

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by GEOFF ELLIOTT & JULIA RODRIGUEZ-ELLIOTT

A NOISE WITHIN

March 1-May 18, 2008

(Opened 3/8, rev’d 3/9)

CAST J. Todd Adams, Jessica Berman, Ronnie Clark, Robertson Dean, Freddy Douglas, Mitchell Edmonds, Geoff Elliott, Dorothea Harahan, Jill Hill, William Dennis Hunt, Kenneth R. Merckx, David Nathan Schwartz, Eric J. Stein, Matt Van Curen, Steve Weingartner, and Jillian Batherson, Jill Maglione, Larry Sonderling and Andy Steadman

PRODUCTION Michael C. Smith, set; Soojin Lee, costumes; Peter Gottlieb, lights; Laura Karpman, music; Rachel Myles, sound; Monica Lisa Sabedra, wigs/make-up; Kenneth R. Merckx, fights; Victoria Robinson, stage management

Geoff Elliott and Jill Hill, center, Freddy Douglas, foreground, back to camera

Craig Schwartz

Smash the mirror

On March 13, when Stephen Sondheim told a UCLA Live audience why he thinks musicals (like his West Side Story, and unlike his Sweeney Todd) can fail to work as movies ("film is reportorial, theater is poetic"), one hardly expected that within the week his articulation would explain a rocky transition in the opposite direction.

Mask, currently in its world premiere at the Pasadena Playhouse (through April 20), is Anna Hamilton Phelan’s musical theater adaptation of her own Oscar-nominated 1985 screenplay. Now, equipped with a Barry Mann-Cynthia Weil sound system and a clear set of directions from Richard Maltby Jr., she is gearing the decades-old vehicle for a trip to Broadway. But prosaic book and lyrics, without the essential additive of poetry, signals that the show may run out of gas upon arrival. That is, assuming it doesn’t get pulled over in Las Vegas.

Telling the true story of Roy L. "Rocky" Dennis, who at the age of 15 had a healthy worldview despite seeing through the distortions of craniodiaphyseal dysplasia, served the Peter Bogdanovich film well. The condition’s street name, "lionitis," hints at its frightful effect of flattening and widening the facial sub-structure. In a stage musical, however, dialogue and lyrics need to do more than tell the story, they need to take it to a higher level.

The ironic thing is that the elements that would have taken the play into other dimensions are visible within easy reach of the story. Like leftover motorcycle parts, while the machine is already speeding down the road, important pieces were left unused on the shop floor.

The plot of Mask remains uncomplicated. Rocky (Allen E. Read) and his feisty, foul-mouthed mother, Rusty (Michelle Duffy), arrive at his new high school in Azusa, California. His comfort with his condition immediately eliminates the familiar arc of an outsider grappling with his fate. Soon, a one-song conversion of his new classmates eliminates the conflict of getting respect from a prejudiced world. Rocky has quickly moved past Quasimodo and Cyrano (not, however, before engaging in a little Cyrano-style tutoring to help the hunk better bed the blonde). But, like both those tragic figures (and most of the rest of us), Rocky’s Waterloo will be women, and in a deeply buried irony, the winning Wellington will be his own mother.

Rusty brushes aside doctor warnings that Rocky has "Three to Six Months" to live. This is the result of her disgust with doctors, but more importantly an inability – despite her bravado – to face reality. The latter point is underscored by her reliance on Methamphetamine, which, in turn, the show becomes reliant on for its strongest arc. Rocky’s story becoming a kind of "Easy Rider" Cyrano determined to bike to Sturgis with "the tribe," the aging motorcycle club that is their extended family. Ultimately, in an effort to shock his mother clean by moving out, Rocky works at a camp for blind teens and has his first real romance with Diana (Sara Glendening in a winning showcase).

Ultimately, of course, a musical is about its music. Pop songwriters of the magnitude of Mann and Weil craft songs that are personal in the singing and universal in the hearing. These two are titans, with dozens of hits to their credit on the order of "On Broadway," "You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin," and "We’ve Gotta Get Outta This Place." While pop tunes are designed to work their magic in three minutes and be done, musical theater songs need to drive narrative action into the next scene, carrying the poetic seed along with them. Mask, however, feels like a series of mini-cycles. Set like pinwheels in the roll of the story arcs they spin here about Rusty’s dependence on drugs, there about her on-again-off-again relationship with Gar (Greg Evigan, whose "A Woman So Beautiful" suggests a Bob Seger musical presence that should be further mined), and then about Rocky’s valiant effort to take to the highway with a hog and a honey.

To the writers’ credit, the addiction story is taken seriously and approached with impressive directness for a Broadway show. But as long as they’re getting messy with it, they might as well go all the way. Rusty’s addiction is the key to the metaphor. The irony that one so tough is hiding – much more than her son, born behind a mask, who refuses to hide – is just not picked up on. That she has made such an extraordinary person of her damaged son, yet falls apart, indicates a complex character that modern audiences need elevated to a place in dramatic art.

Duffy, who is unquestionably appealing, does more here than she’s had to in Can-Can (a breakthrough for her here in Pasadena last year), or the other local musicals she has helped. But, there’s more that needs to be found. Part of the problem is the shallowness of the script, which forces her to rely upon exasperated takes, short-fuse anger, and her beautiful and powerful voice. However, until the story opens up to be about more than a single tragedy in Azusa, it will be more like everything from “A to B” in the USA.

On the plus side, Read is great. He’s boxed in by a limited story, but within that unfortunate cage he’s lion-hearted. Also, the show’s unabashed portrait of a brotherhood of the open road, and the joys of an extended family that watches out for each other, is endearing and could stand to be even grittier. The opening image of gone-to-seed bikers promises something that unfortunately doesn’t fully materialized: a line-up of aged defiance, modern outlaws under long hair, much of it gray, who stand with paunches and pride. What fun it would have been to really pursue this dramatic device with a song like ‘Over the Hill,’ that played on the realities of the AARP generation that grew up (while refusing to grow up) on Mann-Weil music. ('"Climb Every Mountain" and where will you be? Over the hill, yeah, Over the hill.’)

In addition to the shot of Seger there’s a little touch of Townshend in the night. One overdue bit of power chording, recalling the opening crunch of "Baba O’Riley," helps incite the standing ovation. And, if you squint during those closing moments, you might even catch a glimpse of a third dramatic character up there astride Rocky’s heavenly Harley. After recalling Quasi and Cyrano, there’s a minor reminder of Daltry’s blind, deaf and dumb boy, and he also suggests the book writer and bike riders could have given us a more thrilling ride.

top of page

MASK

book by ANNA HAMILTON PHELAN

music by BARRY MANN

lyrics by CYNTHIA WEIL

musical staging by PATTI COLUMBO

musical direction by JOSEPH CHURCH

directed by RICHARD MALTBY JR.

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

March 12 April 20, 2008

(Opened, rev¹d 3/21)

CAST Michelle Duffy, Greg Evigan, Michael Lanning, Allen E. Read, Alec Barnes, Brad Blaisdell, Katy Blake, Ryan Castellino, Diane Delano, Chris Fore, Sarah Glendening, Krysten Leigh Jones, Mark Luna, Heather Marie Marsden, Shanon Mari Mills, Suzanne Petrala, Ethan Le Phong, Jolene Purdy, James Leo Ryan, Matthew Stocke

PRODUCTION Robert Brill, set; Maggie Morgan, costumes; David Weiner, lights; Peter Fitzgerald and Carl Casella, sound; Austin Switser, projections; Michael Westmore, make-up; Carol F. Doran, hair/wigs; Bob Kretschmer, Rocky¹s wig; Steve Margoshes, orchestrations; Jeff Marder, electronic music; Barry Mann, arrangements; Joe Witt/Lea Chazin, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

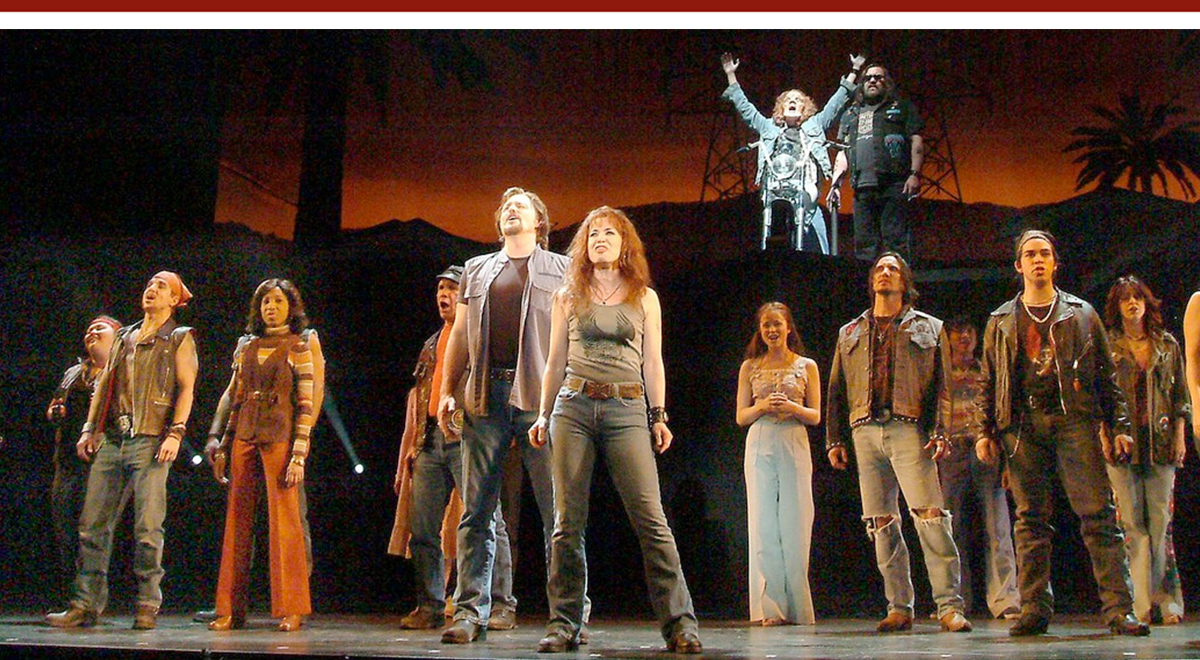

Greg Evigan and Michelle Duffy, center; Allen E. Read, top

Ed Krieger

Teaching art

Emily Dickinson described hope as the feathered thing in the soul that "sings the tune . . . and never stops at all." Were she a student at the Bronx high school that inspired Nilaja Sun’s 2006 solo piece, No Child . . . she’d have likely heard her bird go silent.

As compact and kinetic as its writer-performer, the intermissionless 65-minute No Child . . . , now at Culver City’s Kirk Douglas Theatre through April 13, dramatizes the realities of inner city education following the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2002. Ms. Sun forges a many-faceted character wheel, spinning it at Zoetrope-speed for a keyhole glimpse into a world where hope is often the thing left behind.

Eerily reminiscent of the plots that drove the cheery Garland-Rooney vehicles of nearly four score years ago, No Child . . . hangs its arc on whether or not the play’s Ms. Sun, whose name suggests a story based on personal experience, can cajole, caress or ass-kick one of the school’s toughest classrooms into mounting a play. But their testing of her belief in the eye-opening powers of art will be anything but standard.

Of course, the arc that really interests us is Ms. Sun’s. She arrives an enthusiastic innocent dedicated to sharing her considerable energy and experience. A too frequently unemployed actor, she will lead these students in reading, rehearsing and finally staging Our Country’s Good, Timberlake Wertenbaker’s 1988 stage version of Thomas Kenneally’s novel about convicts in Australia mounting a play. All the while, she’ll be encouraging them to find relevance in the subject matter. This circular, plays-within-plays synchronicity is something made clear by Ms. Sun’s narrator, an ancient janitor who in 1958 was the first African-American hired by the school.

Ms. Sun is confronted by a classroom full of individuals whose only coherence is in being confrontational. But they have their reasons. As she states in an aside, paraphrasing, "79 percent of these students have experienced emotional, physical or sexual abuse." The class’ full-time teacher, Ms. Tam, herself a novice, is railroaded by the students, allowing Ms. Sun some cover to make her own progress with them.

A longer, two-act play could allow us to spend more time with these kids and get to know them. As it is they remain fairly stereotyped and comic, which makes for an enjoyable showcase of Ms. Sun’s unique talent for blending real poignancy with rapid-fire character-changes. While the hour-plus display makes its point and earns its enthusiastic standing ovation, and while there’s no need to turn it into another Lean on Me or Stand and Deliver, there are some pretty wide jump-cuts along the way. In such brief encounters with a wide diversity of characters we're denied the messy nuts-and-bolts of how the students are engaged, turned around and moved ahead. It’s exciting to watch the characters become flash-cards in the spokes of Ms. Sun’s extraordinary high-speed changes, but it would be nice to make time for some longer, deeper visits with a couple key students.

She eventually reaches the point of despair and is willing to leave the project behind. Later, we get a sense of what that abandonment means to students when one boy who made a serious turnaround is unable to take part. Sharing his despair at missing out is the play’s finest moment and might have ended another version of the piece – although to devastating emotional effect (and devastation of positive word-of-mouth). It’s a heart-wrenching scene that lets us feel a little of the pain of one left behind.

The merits of the Federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act, passed in both Chambers of Congress in 2001 and signed into law by President Bush the following January, are in great dispute, and revised legislation, alluded to in the play, is in the wind. It’s likely any top down attempt to "reform" America’s education system, particularly as regards its benefits for poor, abandoned neighborhoods such as New York City’s Bronx borough, would be doomed to failure and savaging.

In No Child . . ., the classroom has become the stage and vice versa. The light of inspiration Ms. Sun took into the real world becomes magnified for theater audiences by its reflection in her play and performance. Without lecturing, we are taught that real change isn’t mandated, it’s inspired.

top of page

NO CHILD

by NILAJA SUN

directed by HAL BROOKS

KIRK DOUGLAS THEATRE

March 6-April 13, 2008

(Opened, rev'd, 3/7)

CAST Nilaja Sun

PRODUCTION Sibyl Wickersheimer, set, based on Narelle Sissons original Off-Broadway design; Jessica Gaffney, costumes; Mark Barton, lights; Ron Russell, sound

HISTORY Premiered at Epic Theatre Center, NYC, May 2006

Nilaja Sun

Craig Schwartz

Demons with haunt you

Marketed as a musical thriller, the long-awaited John Doyle adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s and Hugh Wheeler’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, at the Ahmanson Theatre through April 6, has now earned additional credentials as a psychological thriller. Doyle, whose chamber version is most noted for an arrangement of actors who also play the music, has also tweaked the storytelling. Tobias, who we learned in the first L.A. production 28 years ago, is the story’s soul survivor, now tends to the tale as flashback from his home among the lunatics at Bedlam.

Since Angela Lansbury and Lou Cariou first put their stamps on Mrs. Lovett and Mr. Todd in Hal Prince’s original Broadway staging, "Sweeneys" have lived or died by who played the pussy-popping pastry chef and her beloved butcher-barber. Here, David Hess services Sweeney well, if unremarkably. He has chosen to keep the lid on Sweeney’s fury until well after the arm-completing razor-reunion scene. Once it is unleashed, he fares better, cutting fine renditions of such signature songs as "Priest," "Pretty Women" and the cathartic "Epiphany." However, the strategy means glossing over much of Act I, including the climax of "Poor Thing." That moment, when he learns the fate of his wife and daughter, should blow open a blast-furnace of pent-up rage. It’s structured to singe the audience’s hair yet Hess hardly ruffles it.

Ms. Kaye, on the other hand, joins the front rank of Lovetts, both recalling and surpassing Ms. Lansbury. Despite superb comedic gifts that mine every laugh, she keeps Lovett’s own outrage at life’s inequities threatening to bubble over her pasty shell. Whether singing or acting, her command of the stage is the stuff of Broadway stardom.

But it is Doyle’s concept that most distinguishes this look back down Fleet Street. The opening lines of the show’s Prologue, usually distributed among a scattered chorus of wandering Londoners, now emanates from the solitary Tobias (Edmund Bagnell). He kicks off the story as he is freed from his asylum strait-jacket and hood. It’s frightening to hand over an opera to a madman, but the refocus succeeds in broadening the play’s impact. Sweeney now not only reminds how revenge sucks us into the evil we seek to repay, but how the process spills over onto innocent third parties. That’s an important bonus in a world where drive-bys hit bystanders as often as targets, and parents train their children to perpetuate cycles of abuse. Tobias may have shilled for a "street mountebank," but that hardly merits his damnation.

A side benefit of this new level of twisting the story structure is that, by stationing a wholly unreliable narrator at its center, the events are thrown into question. Certainly, the bones of the story are secure. But there is a new dimension of gamesmanship: Tobias, who spends the play in his blue asylum jammies – the only costume outside the black and white color palate – is recreating the characters with projected images of people from his own broken psyche. The men in the story derive from some authority figure wearing a white dress shirt and tie – a teacher, father or hospital director. This may have been intended – or may be misinterpreted – as the costumes of the Music Hall. But, and here is where it gets fun, in one of those “Back to the Future,” chicken-and-egg time-travel inversions, the sources of Tobias’ characterizations are a combination of people from his own life with the "real" Lovett, Barker, Anthony, et al. Most of the characters have been repressed as too grotesque to recall. And this is why see the safer, happier Music Hall images replacing the too-gruesome recollections of pie and barber slicing. This also explains Mrs. Lovett’s incongruous appearance of the torn hose of a harlot, the hairdo and apron of a housewife and the minstrel’s tuba. Bagnell continues to exercise his central role, watching his story from the perimeter. Sadly, however, his expressions of madness, accompanied by crazy fiddling, sometimes go overboard with facial twinges.

Beyond all that, the most noticeable change in characterizations is the swapping of temperaments between Beadle Bamford (Benjamin Eakeley) and Judge Turpin (Keith Buterbaugh). We now have more of an Othello-Iago dynamic, with the hapless Judge more a victim of his immature cravings for Joanna (Lauren Molina), than a malevolent plotter. As a result, the Beadle's actions are those of the over-stepping sycophant, doing damage to others through his superior. Though we all loved Calvin Remsburg’s bumbing Oliver Hardy of a Beadle, it’s nice to have something different. And, it makes sense as far as it goes.

However, the counter-balancing pull-back of the Judge makes less sense. Perhaps Buterbaugh, who is the weakest performer in the mix, simply doesn’t have it in himself. And, while it may seem tedious to have both men equally malicious, that may ultimately be the perfect answer. After all, the Judge orchestrated Barker’s incarceration, Lucy’s (Diana DiMarzio) deterioration, and Joanna’s isolation from the world. Tobias paints her as virginal, and dressed in a variation of a nightshirt he sees every day. For her part, Molina contributes a delightfully empty-headed Joanna.

As far as the music goes, here too the chamber quality not only conforms to the context of a lone tormented narrator, it reflects Music Hall staging, and allows only the actors on stage to fill the roles. Of those performing, some are clearly accomplished musicians (Bagnell and Molina), and two are ringers. Steve McIntyre’s bass gives the entire score its foundation, while minimal acting is required for his one character, asylum director Jonas Fogg. Katrina Yaukey, who knows her way around the piano and accordion keys, moves around the stage as part of the chorus, then portraying Pirelli (whose scene, as is now custom, includes only the hair-cutting competition while pulling the tooth-pulling contest).

And, last but not least, Benjamin Magnuson’s Anthony, which takes some getting used to as he seems pretty light at the beginning, is ultimately winning, especially for his clarity on a number of numbers that involve dueting through some of the show’s most difficult passages with Molina.

As will likely be said again and again in these pages, we’ll take a competent night of Sondheim over the finest production of any other musical theater composer. There you have it: fool disclosure. In John Doyle’s imaginative and wholly integrated vision, one not only gets the brilliance of Sondheim at the peak of his creative genius, we get another entire level of meaning, adding a dimension of demented gamesmanship. Who would have thought such a thing possible. For anyone who loves language for as more than a way to order pizza and bad-mouth the neighbors, for whom the Mother Tongue means more than Oedipal Frenching, Sondheim is the reigning godhead. A Will Shortzean fireworks display like ‘Have a Little Priest,’ where the lyricist parks the story for a bit of fun, allows us to luxuriate in language just as Lovett and Todd feast on their shared misanthropy. It’s proof of heaven, as you’re living.

top of page

SWEENEY TODD, THE DEMON BARBER OF FLEET STREET

by STEPHEN SONDHEIM

by HUGH WHEELER

directed and designed by JOHN DOYLE

AHMANSON THEATRE

March 12-April 6, 2008

(Opened, rev’d 3/12)

CAST Edmund Bagnell, Keith Buterbaugh, Diana DiMarzio, Benjamin Eakeley, David Hess, Judy Kaye, Benjamin Magnuson, Steve McIntyre, Lauren Molina, Katrina Yaukey, and Edwin Cahill, David Garry, Megan Loomis, Elisa Winter

PRODUCTION Richard G. Jones, lights; Dan Moses Schreier, sound; Paul Huntley, wigs/hair; Angelina Avallone, makeup; David Loud, music direction; Sarah Travis, music supervision and orchestrations; Adam John Hunter, associate direction; Newton Cole, stage management