OCTOBER 2009

Click title to jump to review

CREDITORS by Doug Wright | La Jolla Playhouse

THE HAPPY ONES by Julie Marie Myatt | South Coast Repertory

MOONLIGHT AND MAGNOLIAS by Ron Hutchinson | Laguna Playhouse

PARADE by Alfred Uhry and Jason Robert Brown | Mark Taper Forum

RICHARD III by William Shakespeare | A Noise Within

SAMMY by Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley | The Old Globe

THE SAVANNAH DISPUTATION by Evan Smith | The Old Globe

Getting Strindberg Wright

Doug Wright has applied his Pulitzer Prize-winner cachet and some La Jolla Playhouse cash to an adaptation of August Strindberg’s Creditors, a twisted tale of marriage and manipulation. Wright also directs the world premiere (at the commissioning Playhouse through October 25). Focusing on the intellectual cat-and-mouse game and minimizing the melodrama creates a frosty portrait of human interaction. While this would please Strindberg and his acolytes, the chill factor generates a tepid audience response and a cool curtain call that is no reflection on the excellent ensemble.

Strindberg, who died at 63 in 1912, wrote novels and plays, painted with oils, photographed, and dabbled in alchemy. Like his wide-ranging talents, his work, while usually playing out in conflicts between the sexes, projected larger conflicts about economics, politics, philosophy and religion. Creditors, which the writer considered among the three best of his ultra-naturalistic period (with The Father and Miss Julie), was written near the bitter end of a brief second marriage. Creditors may owe its underlying spitefulness to bleed-over from that anti-romantic experience.

The intermission-less play is set in a large seaside hotel and divided into three scenes, each with a different pairing of the three characters. First, we meet Adolf (Omar Metwally) and Gustav (T. Ryder Smith), then Adolf and his wife, Tekla (Kathryn Meisle), and finally Gustav and Tekla. The play begins as Adolf bares his soul about his love for Tekla, who, after leaving him at some point during their vacation stay, will rejoin him later that day. As Adolph looks for hopeful signs in his wife's behavior, Gustav dashes each one, attributing the trouble not to an imbalance in affections but to defects in women. This is an example of why Strindberg is often branded a misogynist. It is more likely that these feelings belong to the character – and even there are being used for effect.

Furthermore, the idea of "creditors," that those who are beloved are beholden to the lovesick, does not appear to be gender-based. Rather, it is the key to justifying Gustav's pursuit of vengeance.

This becomes apparent when we sense that Gustav may be widening the gulf between the estranged spouses to create room for himself to enter. Adolph, and the audience, are unaware that Gustav is, as the script makes clear on page one, Tekla's "divorced husband, a high-school teacher who is traveling under an assumed name."

This information might make the play more engaging, because we are so out to sea on what's going on. We are pushed further out when the men talk about Tekla’s first husband. Especially since the philosophic discussion, about women being a malevolent, untrustworthy breed, fills such an extended period (by today's measure) with dismissible – and toxic – gas. After the first scene, which ends with the gents setting a kind of trap for Tekla, events begin to gather momentum, until all is revealed.

Smith, vocally and physically, gives the lanky Gustav a wily look and suspicious veneer, while Metwally does well creating a physical and emotional wreck. Meisle’s Kathryn is powerful, yet clearly not the overbearing creature the men describe. She may be willing to enter into deceit, but is not going to be indifferent.

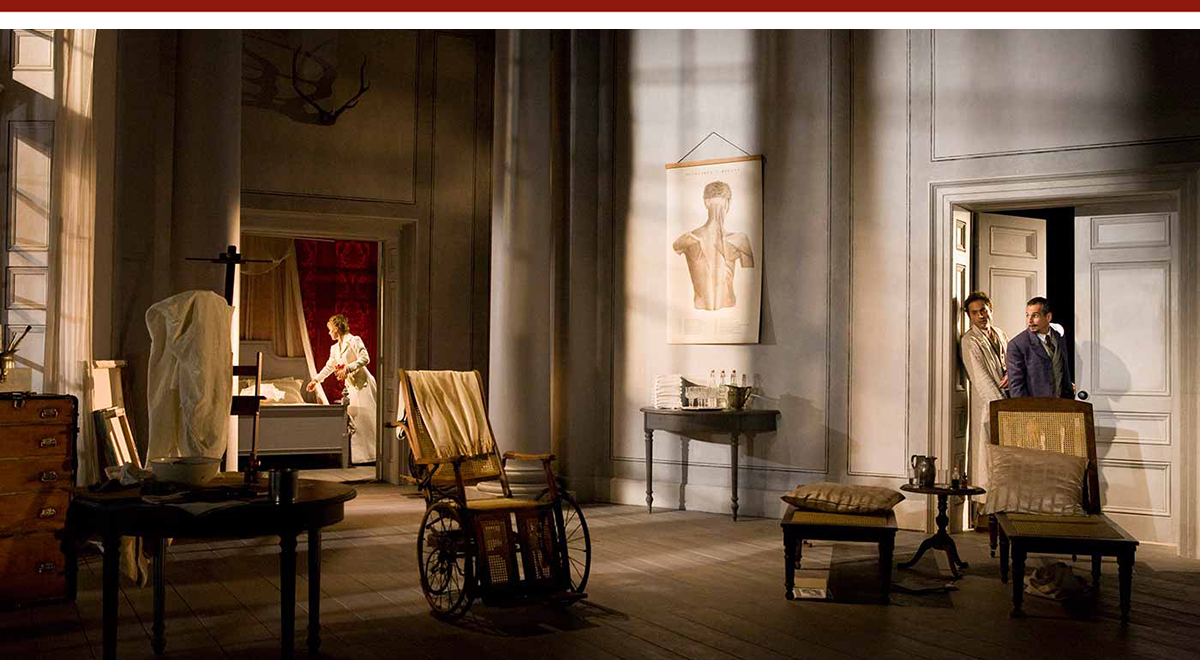

It is a beautiful production. Brill’s design, which is somewhat confusing as its profusion of wheelchairs makes it appear more a sanatorium than the “summer hotel” proscribed by the script, employs a severely forced perspective that angles its tall white walls like bared thighs to an upstage bedroom door. To complete the visual metaphor, the door opens on a bed flanked by the set's only vivid colors –a frame of rich red drapes.

Susan Hilferty’s costumes are beautiful, extending the off-white/blue-gray earth-tone palette used by Brill. The exception, again, is Tekla’s elegant white gown. Japhy Weideman goes to some trouble to send softly wavering mottled light up through the stage right windows, suggesting reflected sunlight from the sea below. A lovel trick. David Van Tieghem and Jill BC DuBoff provide original music and sound, respectively, to this elegant staging.

top of page

CREDITORS

adapted and directed by

DOUG WRIGHT

based on the August Strindberg play

translated by Anders Cato

LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE

September 29-October 25, 2009

(Opened 10/4; rev’d 10/11m)

CAST Kathryn Meisle, Omar Metwally, T. Ryder Smith

PRODUCTION Robert Brill, set; Susan Hilferty, costumes; Japhy Weideman, lights; David Van Tiegham, music; Jill BC DuBoff, sound; Tom Watson, wigs; Shirley Fishman, dramaturg; Jennifer Leight Wheeler/Erin Gioia Albrecht, stage management

HISTORY World premiere. Commissioned by La Jolla Playhouse

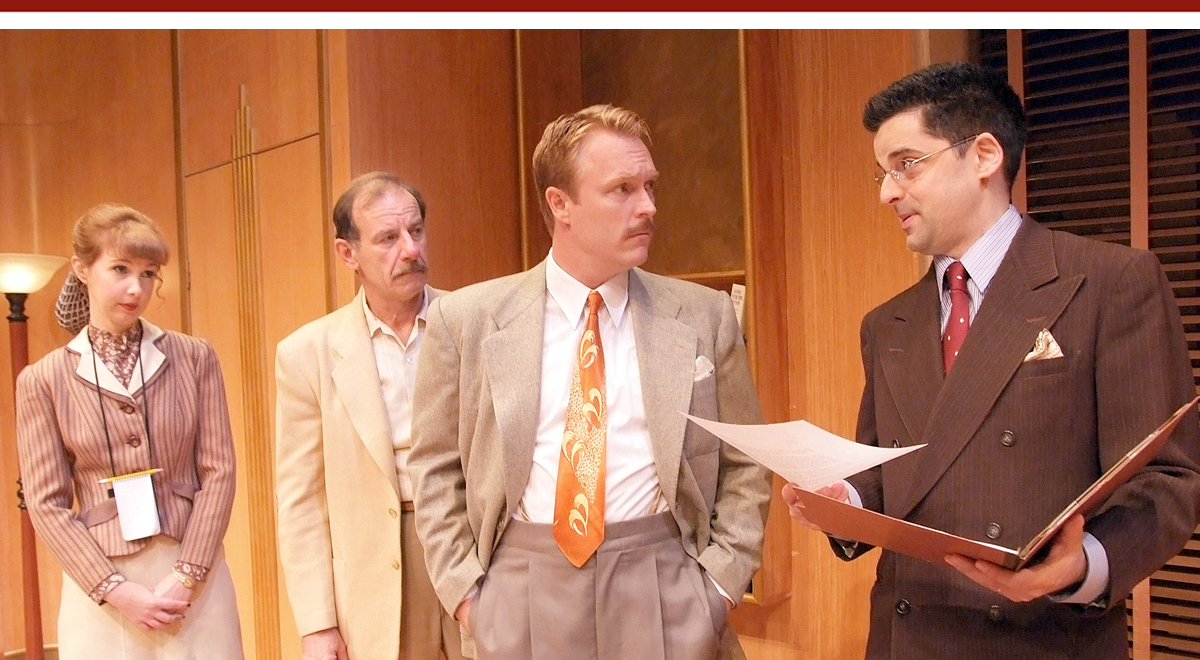

Kathryn Meisle, Omar Metwally, T. Ryder Smith

Craig Schwartz

God and Sinners Reconciled

Putting playwrights on the map is something South Coast Repertory pursues through play commissions. In The Happy Ones, her second SCR commission, Playwright Julie Marie Myatt returns the favor. The play, a tragicomic look at the redemptive power of forgiveness, could only happen in Orange County. Nevertheless, the light that Myatt sheds on her four well-defined characters projects cautionary shadows far beyond the county borders.

Like the film Crash or the play Rabbit Hole, The Happy Ones, receiving its world premiere (through October 18) under Martin Benson’s direction, uses a deadly collision to connect lives that would otherwise never intersect. Strangers, suddenly fused in the cause and effect of tragedy, must work through their burning anger together or be consumed by it alone.

Between 1950 and spring 1975, only 650 Vietnamese emigrated to the United States. Then, in the single season surrounding the fall of Saigon, more than 125,000 arrived under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Act. The largest portion would settle in the Orange County cities of Westminster and Garden Grove, where the play is set.

Following the April 30 evacuation of Saigon, Bao Ngo (Greg Watanabe), an English-speaking Vietnamese doctor, comes to America ahead of his wife and children, and soon learns that they will never join him. Suddenly stripped of his family by forces outside of his control, he descends into months of depression that finally subside enough for him to take a tentative driving tour of his new homeland. It is then that a wrong turn sends him headlong into the family of Walter Wells (Raphael Sbarge).

Walter is a middle-class American dream come true. He owns an appliance store, lives in the spacious Eichler-inspired home that is the suggestion of Ralph Funicello’s beautiful set. As the play opens, he is checking the kids in the pool and mixing drinks and music for his offstage wife. Like the pool and the cocktail, the life of Walter Wells (whose name ripples with metaphoric possibilities) is disturbed only by the playfulness of his wife and children.

Now, days later, like a jumbo jet crashing into his yard, a calamity of unfathomable scope catapults him into the unknown. In Rabbit Hole, which this will surely be compared to, David Lindsey Abaire follows a mother who lost her child in a car accident. While she begins to see her own healing linked to easing the teenage driver’s torment, her husband holds his fury sacred, maintaining it like the eternal flame on Kennedy’s grave. Myatt takes on the tougher challenge of burrowing after this inconsolable father.

Turning Walter around is a huge dramatic endeavor, like tacking a tanker 180 degrees inside a canal lock. His self-righteous rage is primal, and justifiably beyond the province of logic. All the casseroles delivered by Mary Ellen (an impeccable Nike Doukas) and the homilies delivered by her boyfriend Gary (Geoffrey Lower), who is also Walter’s best friend and Unitarian Minister, fall well short. It will take a long time to heal this wound, and Myatt has just over two hours. But Bao, who somehow seems even more devastated, offers to work off his cosmic debt through service. Walter refuses, but the distraught stranger in this strange land is insistent. Dramaturgically earning the turnaround, especially given Myatt’s admirable commitment to avoiding easy answers, may need more tweaks. The first coffee-drinking scene, where the tanker begins to be twisted, creaks a little under the stress load.

Benson finally seems to have another of the kind of script that made him one of the region’s most acclaimed directors. He also has a quartet of gifted actors inspired to work at the top of their craft. It’s safe to say there won’t be a better ensemble on any stage this season. Oonh Nguyen, the artistic director of Anaheim’s Chance Theater, assures the play its Vietnamese authenticity, and perhaps some of its energy.

Sbarge makes his SCR debut after several readings, including a public reading of The Happy Ones. His Walter Wells is the everyman thrust into Greek tragedy. His evolving response to a crank caller is tender, and camouflages Myatt’s clever device to give him late-play perspective by pulling him out of himself. After showing us the violent depths of Bao’s self-hatred, Watanabe drains his character of emotion. The ghost that remains is still painfully human, and yet the actor can use that emptiness, without compromising the realities, for a deadpan delivery that adds to the play’s surprising supply of humor.

Doukas, a frequent board-walker here, creates one of her greatest contributions. Her Mary Ellen is the life of the party, an intuitive presence always just a half-step shy of self-realization. Determined not to let life pass by, even as she fumbles to define it, she is a dance-on-the-table, conga-line-launching fun-pack. Doukas gives Mary Ellen - and the play's double-edged title - all the depth Myatt could have hoped for. In Lower’s Gary, she has found a complementary spirit – a life-long bachelor minister whose devotion is watered-down to a level he would find unacceptable in a cocktail.

The elephant in the room is responsibility. While the characters wrestle with responsibility for their own lives and how they impact others, their dark shadows cast aspersions on the behavior of nations. That we are in an era of reconciliation makes this a play for its time, and hopefully, all time.

Special nods to Angela Balogh Calin for restrained period costumes, Tom Ruzika for lights, and especially Paul James Prendergast for a sound design that includes both Asian and American music – including some well-timed hits from the day.

top of page

THE HAPPY ONES

by JULIE MARIE MYATT

directed by MARTIN BENSON

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 27-October 18, 2009

(opened 10/2; rev’d 10/10m)

CAST Nike Doukas, Geoffrey Lower, Raphael Sbarge, Greg Watanabe

PRODUCTION Ralph Funicello, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes; Tom Ruzika, lights; Paul James Prendergast, sound; John Glore, dramaturg; Jennifer Ellen Butler, stage management

HISTORY Commissioned by South Coast Repertory; an Edgerton Foundation New American Plays Award; NewSCRipts reading

Nike Doukas, Greg Watanabe, Raphael Sbarge, Geoffrey Lower

Henry DiRocco

Shooting scripts

In “Gone with the Wind,” novelist Margaret Mitchell traced the Confederacy’s decline against the squandered prospects of a Southern beauty. David O. Selznick quickly obtained the rights to the international bestseller to launch one of Hollywood’s legendary high-wire, high-risk film-producing feats. He would mow through a dozen directors and screenwriters in a compulsive drive worthy of General Sherman's march. In January 1939, after firing director George Cukor, he locked himself in his office with incoming director Victor Fleming and writer Ben Hecht for round-the-clock rewrites. When they emerged a week later, Selznick had a shooting script and the movies had a new myth”

Sixty-five years later, in the 2004 comedy “Moonlight and Magnolias,” Playwright Ron Hutchinson would take us inside Selznick’s office to relive those pressure-filled days of reshaping <em>Gone with the Wind</em>. The Laguna Playhouse is offering an amiable staging (through November 1) under the direction of Artistic Director Andrew Barnicle.

Like the outsized, conflicting personalities of the men stuffed into Selznick’s office, the components of Hutchinson’s play are occasionally at odds. Supercharged, highly physical slapstick generated by men under enormous stress periodically yields to relaxed, philosophical exchanges about the nature of art and politics – especially the cause of a Jewish state, which Hecht tirelessly promoted.

For the most part, Barnicle succeeds in having it both ways, thanks chiefly to Jeff Marlow, who keeps things moving with plenty of variety – from the light touch to the heavy-handed stomp this kind of comedy inevitably receives. As Hecht, Leonard Kelly-Young feels stiffer than necessary, portraying a serious Hecht who skews towards the show’s philosophical demands and dulls the comedy. Brendan Ford’s Victor Fleming is generally pleasing. The lone woman, Emily Eiden, as Selznick’s obedient secretary, is delightful. Eiden is capable of the kind of rubber-faced comedy that made Carol Burnett camera-ready and Kristen Lowman a local stage favorite a couple decades ago.

The show requires a realistic set, and the Playhouse has done it right with Bruce Goodrich’s richly paneled, perfectly detailed period office. Julie Keen’s costumes are spot on, and Paulie Jenkins lights the room effectively. What there is of Julie Ferrin’s sound design complements the proceedings nicely.

top of page

MOONLIGHT AND MAGNOLIAS

by RON HUTCHINSON

directed by ANDREW BARNICLE

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

October 6-November 1, 2009

(Opened, rev’d 10/10)

CAST Emily Eiden, Brendan Ford, Leonard Kelly-Young, Jeff Marlow

PRODUCTION Bruce Goodrich, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Paulie Jenkins, lights; Julie Ferrin, sound; Rebecca Michelle Green, stage management

HISTORY Developed at McCarter and Ojai Playwrights Conference; premiered at Woolly Mammoth Theatre (DC), August 2009 • West Coast Premiere