OCTOBER 2010

Click title to jump to review

FDR | Pasadena Playhouse

IN THE NEXT ROOM, OR, THE VIBRATOR PLAY by Sarah Ruhl | South Coast Repertory

MISALLIANCE by George Bernard Shaw | South Coast Repertory

THE ROAD TO MECCA by Athol Fugard | San Diego Repertory

THE TRAIN DRIVER by Athol Fugard | Fountain Theatre

WELCOME TO ARROYO'S by Kristoffer Diaz | The Old Globe

Recovery act

The Pasadena Playhouse is making its return to producing with a smart first step: a one-man show about a president taking office in the middle of high unemployment and historic economic crisis. And, playing that president is a beloved television actor. Small cast, big benefits: Happy days are here again.

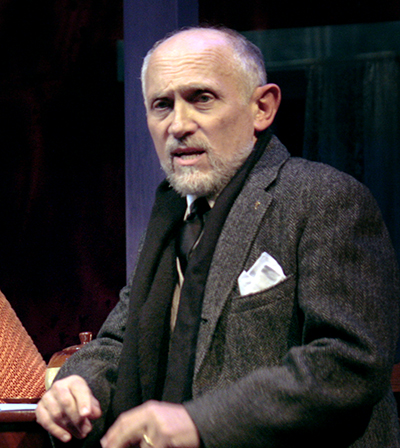

Everyone wants the Playhouse to succeed for a fourth term. Even the Los Angeles Times gave the show, FDR starring Ed Asner, a big feature despite the fact that it was just down the road in La Mirada five months ago. We do too, which is why we’ll begin by saying the performance drew a standing ovation for Mr. Asner and should satisfy his many diehard fans.

Fans of drama, however, may find the show’s vague progression and Mr. Asner’s understandably muted energy (he is 80) to be what makes the 90-minute show run a little long, and feel even longer.

Some of the pacing is due to the strange genetics of the piece. Originally, Dory Schary wrote Sunrise at Campebello as a 25-character play that arrived on Broadway in 1958, roughly 14 years after Franklin Roosevelt's death, and stayed for 556 performances. How it got from there to this adaptation for a single actor is unclear. (The program lists only a mysterious bio-less Allan William; no adapter or director.)

There are numerous instances in which FDR "jump-cuts" from FDR the first-person storyteller to conversations between the 32nd President and an invisible First Lady, assistant, or cabinet member. The audience is suddenly mere onlookers trying to sort out where they are. Clearly, the distillation of Sunrise to solo show needed to be more radical. When the tenets of one-person storytelling are respected – and some of the time they are – we are ushered into the conversation by way of a set-up that establishes the context.

A strong case could be made that Roosevelt was America’s greatest president. His rise from a pampered only child on the vast Hyde Park estate, to a fish out of water in his boarding school and Harvard, to his marriage to a first cousin, to someone who overcame paralysis to makes him one of the most extraordinary people this country has produced. He had his case of backsliding, with an affair that is widely documented and that his equally extraordinary wife, Eleanor, forgave him and moved on.

There is no effort made to imitate Roosevelt’s voice, which is just as well, and the fact that Asner lacks physical resemblance is not a problem. The energy and boundless enthusiasm that was the signature of the New Deal's architect is what seems lacking. Asner makes an effort, with occasional belly laughs and wry jokes. But those jokes are delivered with more of Mr. Grant's sneer than Mr. President's toothy grin.

That said, it's great to be back in the state's landmark theater. The sun may already be rising over El Molino. This week the theater announced that its "Hothouse at the Playhouse" program will return October 28-29 with a reading of Jason Aaron Goldberg's The Confessions of Deacon Jim.

top of page

FDR

by Dore Schary

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

October 13 – November 7, 2010

(Opened 10/13, Rev’d 10/16m)

CAST Ed Asner

PRODUCTION Allan Williams, dramaturg; Ron Nash, stage management

HISTORY Based on Dore Schary’s Sunrise at Campobello, FDR debuted on September 25, 2009 at The Door Community Auditorium in Fish Creek, Wisconsin. Produced by Campobello Theatre Productions and Gero Productions LLC.

Ed Asner

Theater Guild

Pulling out the stops

Sarah Ruhl’s recent plays – The Clean House (2006) and In the Next Room (2009) – are not about selling property, but about shedding propriety, embracing intimacy and living more fully. The recent one, subtitled "the vibrator play," is now at South Coast Repertory (through October 17) in a beautiful production directed by Casey Stangl. (San Diego Rep will stage it in March.)

Ruhl has rich turf to explore in her period piece and Stangl’s design team gives SCR's shops a chance to show their chops. Under David Ionazzi’s tempered lighting, John Arnone’s set creates a balance of abstraction and representation while David Kay Michelson’s realistic costumes include several Smithsonian-worthy gowns.

Those who assumed the vibrator was a recent invention will be surprised to discover it is more than a century old and of noble birth. According to Rachel P. Maines’ The Technology of Orgasm (Johns Hopkins Press, 1999), it was conceived as a labor saving device for physicians treating "hysteria," literally "womb disease."

In the opening chapter, "The Job Nobody Wanted," Maines explains that for millennia physicians had been treating women for depression by bringing them to orgasm. Apparently, for women to earn man's patience, they had to become his patients. In 1653, Pieter van Foreest wrote that"when these symptoms [hysteria] indicate, we think it necessary to ask a midwife to . . . massage the genitalia . . . And in this way the afflicted woman can be aroused to the paroxysm." However, he advised, for married women, "a better remedy [is] to engage in intercourse with their spouses."

In the Next Room takes us to the 1880s and the dawn of applied psychology and electricity. In his operating theater off the living room he shares with his wife Catherine (Kathleen Early), Dr. Givings (Andrew Borba) has a new contraption for treating women. Givings, or his assistant Annie (Libby West), sets the machine's vibrating plastic tip against a patient's uterus to release the paroxysm, "a sudden, emotional outburst or fit of violent action." The irony is that thick-as-a-brick Givings doesn't equate the paroxysm he produces to exorcise hysteria with the orgasm van Foreest said husbands should provide through intercourse. Mr. Daldry (Tom Shelton), another spouse missing the point, brings his wife Sabrina (Rebecca Mozo) to Givings for help with her listlessness. Givings interviews Mrs. D., scribbles some notes, and cranks up his wonder machine – a magnificent prop – and has soon aroused the primal forces of nature, opening her floodgates and restoring her joie de vivre.

Understandably, Sabrina is soon back for follow-up sessions and it isn’t long before Catherine hears the cries of religious epiphany through the wall. Catherine, depressed over problems breastfeeding her baby, requests her own session. The Daldrys’ maid, Elizabeth (Tracey A. Leigh), recently lost her baby and agrees to be employed as a wet nurse. But that only adds to Catherine’s feeling of inadequacy. Still, Givings doesn't believe she is ill enough for the funcooker.

There are far fewer layers of female undergarments for Givings to get past than layers of denial in the men. But Ruhl's play sets out to drill through them. The active agent she'll employ to get things bubbling is a surprise male patient who arrives seeking help. Leo Irving (Ron Menzel), an artist with "painter’s block," will have that block blasted by a posterior-probing variation on the vibrator. His sensitivity flowing again, he is irresistible to the love-starved Catherine, who decides to leave her machine-enamored husband and follow Irving to Italy.

Early is a delight, introducing Catherine as a Gracie Allen savant innocently tossing off insights wrapped in inanities, then evolving her into Catherine on a Hot Tin Roof. (Coincidentally, the actress has played Tennessee Williams’ femme fatale and has a one-woman show called Hysteria.) Mozo’s Wynona Ryder doe-eyes get a great workout, shifting from sad curiosity to ecstastic conversion. Other than furthering Catherine’s sense of inadequacy, it’s not clear what Elizabeth is doing here. Both the "upstairs/downstairs" and racism themes she suggests are non-starters. Yet, Leigh does fine work making her seem real and essential. The versatile West makes Annie a quiet force of understanding.

Borba creates a focused portrait of the out-of-touch Givings, and Shelton reins in his remarkable rubber face to keep Daldry real, funny. Menzel takes advantage of Irving’s unique function in the play to add plenty of dash.

While the women back into awareness – a legitimate and necessary element in an environment that stymies direct puruit of self-fulfillment – that passivity infects the play, giving it a sense of floating to its resolution rather than driving to it. That eventually changes, but not before it produces some languishing deep in the second act.

That does not diminish the overall impact of this Tony Award nominee. Stangl and her excellent cast keep things on track for a glorious, encouraging climax in which the designers pull out all the stops.

top of page

IN THE NEXT ROOM, OR, THE VIBRATOR PLAY

by SARAH RUHL

directed by CASEY STANGL

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 26-October 17, 2010

(Opened 10/1, Rev’d 10/2e)

CAST Andrew Borba, Kathleen Early, Tracey A. Leigh, Ron Menzel, Rebecca Mozo, Libby West

PRODUCTION John Arnone, set; David Kay Mickelson, costumes; Daniel Ionazzi, lights; Jim Ragland, music/sound; Philip D. Thompson, dialect; Kathryn Davies, stage management

HISTORY Originally commissioned and produced by Berkeley Repertory Theatre. Developed at New Dramatists; original Broadway production at Lincoln Center Theater (2009)

Kathleen Early, Andrew Borba and Rebecca Mozo

Henry DiRocco

Allied forces

Though the only "misalliance" George Bernard Shaw cites in Misalliance is marriage between members of different classes, there are others in his sights. The one that most mystifies him is a natural one, between parents and their children. Misinterpreted as mere misanthropy when it premiered in Britain in 1910 and in the U.S. seven years later, Misalliance would finally find a worthy ally in Southern California, more than a generation after the playwright’s death in 1950.

South Coast Repertory struck gold when it first revived Misalliance in 1987, earning a half-dozen Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle Awards, including one for Artistic Director Martin Benson’s staging. Now this less-admired of Shaw’s work has been re-revived (through October 10). Again positioned to open a season under Benson's direction, and featuring Ralph Funicello’s carbon copy of his earlier set (again lit by Tom Ruzika, with costumes by Maggie Morgan and Michael Roth's music), can they coax lightening to strike twice?

Yes they can.

It’s hard to see how so many missed the boat a century ago. Max Beerbohm of the Saturday Review called the characters "perfunctory," and replicas of previously introduced figures. "Only by his righteous indignation against what he takes to be mankind," he added, "is [Shaw] enabled to go on with the task of fashioning them." There was the occasional rave, of course, though Shaw may have preferred Beerbohm’s tongue-lashing to the slobbering-over he received from Henry Mackinnon Walbrook, whose Pall Mall Gazette review included this backhanded compliment: "Misalliance is . . . a caprice, the most whimsical thing in the world, a piece of nonsense almost from beginning to end, but of a nonsense having so much wit and so much sense that it never bores."

Again Benson finds the right spirit to enliven the "righteous indignation," making it great fun without making it "nonsense." The whole affair, from the sunny skies of Funicello’s birdcage-solarium set, to the energy in every performance, carbonates the Shavian dogma with theatrical Life Force. Benson’s greatest ally is the marvelous Dakin Matthews. As the family’s head and play’s tent pole, Matthews' John Tarleton is filled to bursting with the love of ideas and the finer ways of expressing them. "Read Shakespeare," he exults. "He has a word for every occasion!"

Also putting in star turns in secondary roles are JD Cullum and Kirsten Potter. As "Gunner," Cullum is an armed intruder bent on forcing Tarleton to apologize for mistreating his class and kin. As stunt-flyer Lina Szczepanowska, Potter makes the stern Pole a font of comic absurdity. One would be hard pressed to come up with two performances in the same show that, without ever the cracking of a smile, produced so much laughter.

The key to the show’s inner balance is the relationship between Tarleton and his daughter Hypatia (Melanie Lora). Teelingly, Shaw, by way of Tarleton, names Hypatia after the 4th Century woman who followed her father, Theon, into the sciences, became "the first notable woman in mathematics," and died at the hands of Christians. A martyr to reason, if you will. (Read the Encyclopedia Britannica!)

Lora’s Hypatia strikes the balance between independence from and admiration for her father. She is the heiress apparent to his ready love of fun, while her brother, John Jr. (Daniel Bess), takes after their left-brained mother (Amelia White), who bustles about the home, tending to the guests and gingerly grounding her husband’s wilder pronouncements. At 30, Hypatia is unmarried and living with her parents. But she is engaged to Bentley Summerhays (Wyatt Fenner), the wispy intellectual son of Lord Summerhays (Richard Doyle), an old military man and friend of Tarleton’s. Hypatia's unlikely vision of a mate reveals her warring hemispheres – one to stimulate her mental and carnal sides. She has not found a suitable suitor and so settled for the brainy Bentley, who can satisfy her intellectual demands.

Her salvation arrives from the heavens with the crash landing of dashing Joey Percival (Peter Katona) and his passenger, Szczepanowska. A handsome figure promising adventure, Percival quickly turns Hypatia’s head away from her fiance, while all the men onstage are smitten with the downed aviatrix. Before night, the romantic alliances will sort themselves out as Shaw works to sort out families and the societies that they build to support themselves.

In Parents and Children, the 124-page preface to Misalliance, the childless Shaw detailed his views of raising, educating and respecting our offspring. With plays and essays his only issue, he nevertheless advises us that one's children are the only proper way to pursue immortality – rebirth through "remanufacture." That obviously was not going to happen for him. Instead, his work will mark his return to us. Misalliance has now been remanufactured twice, a generation apart, here in Southern California, with its intellectual and physical demands satisfied. And that is especially satisfying for one fortunate enough to attend production with the 23-year-old daughter who was born on the morning after the 1987 production opened.

top of page

MISALLIANCE

by GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

directed by MARTIN BENSON

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

May 12-July 3, 2010

(Opened 5/15, Rev’d 10/3m)

CAST Daniel Bess, JD Cullum, Richard Doyle, Wyatt Fenner, Peter Katona, Melanie Lora, Dakin Matthews, Kirsten Potter, Amelia White

PRODUCTION Ralph Funicello, set; Maggie Morgan, costumes; Tom Ruzika, lights; Michael Roth, music/sound; David Neville, dialects; Oanh Nguyen, assoc. dir.; Jamie A. Tucker/Chrissy Church, stage management

Full cast, top; Inset: Dakin Matthews, Kirsten Potter

Henry DiRocco

Beware of darkness

Athol Fugard’s The Road to Mecca, currently onstage (through October 17) at San Diego Rep, is a tribute to artistic integrity and indomitability. Inspired by the story of South African sculptor Helen Martins, it is clearly fueled by Fugard’s own belief that an artist must follow a personal path lit from within.

Associate Artistic Director Todd Salovey directs the 1987 play with Kandis Chappell as Martins, Amanda Sitton as her young friend Elsa Barlow, and Armin Shimerman as the Rev. Marius Byleveld, the leader of the local church and Martin’s only remaining neighborhood friend.

Martins turned her home into a work of art, filling her yard with a gallery of odd statuary. The property became known as "Owl House," and has since become a national monument. Any of her figurines that can, raise a limb eastward, toward Mecca.

In Fugard’s interpretation, Mecca is both destination and the determination to reach it. Barlow’s road brought her to Helen years before. The statuary caught her eye and she stopped to inquire, developing a master-student dynamic with the woman she came to idolize. She would routinely make the 1600-mile round trip to visit Helen, and fill in the time between with steady correspondence.

As the play begins, Barlow arrives after three months of not visiting or writing. During that time, Helen has been increasingly frightened by weakening eyesight, mental lapses, a loss of strength in her hands, and a sense of depression intensified by her feeling of abandonment by Barlow. It has increased her alienation from the other villagers and her reliance on Marius, who believes Helen now needs the safety of a residential facility.

While Marius’ regular visits have eased Helen to accept the rare vacancy that has opened at "the home," Barlow’s silence scared her into writing a trenchant cry for help. That letter, hinting at an enveloping darkness of suicidal proportions, set Barlow on the road to investigate. She arrives just before Marius comes to retrieve Helen’s signed application for admission to the facility.

As is his custom, Fugard writes conversational dialogue that takes its time getting where it’s going. It affords the actors plenty of time to paint their characters. Here, with the action taking place in real time over a single evening, metaphors of light and darkness are employed – almost overemployed – to illuminate the fine points. Helen’s creative freedom is what is at stake here. Marius, who has lost a wife, can accept the end of the light; Barlow, who is young – and is guilty about recently opting out of motherhood – rages against any diminishing of her spirit.

Chappell, one of the West Coast’s great stage actors, doesn’t disappoint, creating a powerful and sympathetic character. What she is kept from in Salovey’s vision, is showing more of the dominating presence that earned the love and respect of both her friends. Here we have a post-glory Helen, beseeching Barlow's affections rather than earning them. For the better part of the play she is brow-beaten by Barlow, whose temperment quickly hits high dudgeon and remains there. It's in the text to say these things, but it's in the relationship – and the interest of the experience – to deliver them with some measure of reluctance, compassion and respect. Also, it needs to be taken with less yield and more resistence from Helen. .

Shimerman, on the other hand, is perfection. His Marius is self-assured in its affection for Helen. But, where as Barlow’s anger becomes the dominant mode of communication, his inclination to overprotection quickly appears patronizing. Barlow’s advantage is that she understands Helen’s true nature, and they have a special bond. Marius does not. His position is sanctified by religious authority, and their friendship's resemblance to romance.

Because it is the house, as a work of art, that validates Helen’s unique talent and lets us see her visions, the set is an important element of any production of this play. Given the metaphor, the light design is even more crucial. Budget limits what Giulio Cesare Perrone’s set can be expected to do. Nevertheless, it’s a let down. The big moment of transcendence, when lighted candles are meant to fire up tiny mirrors embedded throughout the walls and take us into Helen’s imagination, is missing. Ross Glanc’s lights start beautifully, but soon hit a single bright cue, and do not find a more palatable palette until Barlow’s "Love/Trust" section. Throughout the show, changes in light cues – and Bruno Louchouarn’s sound cues – draw too much attention to themselves.

There is a beautiful message of Zenlike subtlety in Fugard’s use of "Mecca" and "Road." Artists especially, but all people really, are both on the road to reach their destination – their promise – and they are at the same time, the destination they seek. More than once, Helen says, "I’ve reached my Mecca. . .. This is as far as I can go." It is as much revelation as it is resignation. The production, too, inspires both those reactions.

top of page

THE ROAD TO MECCA

by ATHOL FUGARD

directed by TODD SALOVEY

SAN DIEGO REPERTORY

September 25-October 17, 2010

(Opened, Rev’d 10/1)

CAST Kandis Chappell, Armin Shimerman, Amanda Sitton

PRODUCTION Giulio Cesare Perrone, set; Mary Larson, costumes; Ross Glanc, lights; Bruno Louchouarn, music; Tom Jones, sound; Jan Gist, dialects; Heather Brose, stage management

HISTORY Originally produced by Yale Repertory Theatre The play was performed at the National Theatre in London and then moved to the Spoleto Festival USA in 1987 starring Athol Fugard as the Rev. Marius Byleveld and Yvonne Bryceland as Miss Helen. The play won the 1988 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Foreign Play.

Kandis Chappell and Amanda Sitton, top; inset: Armin Shimerman

Daren Scott

Wheels on fire

At rise, Simon Hanabe stands over the gravel wasteland that is the setting for Athol Fugard’s The Train Driver, having its U.S. premiere in Stephen Sachs' staging at the Fountain Theatre (through December 12). His bowler, baggy pants and lean look of the lost make him appear the African cousin of Beckett’s Didi and Gogo.

Fugard’s latest is a small but Shakespearean slice of storytelling that turns on ancient fears and callous fates. It’s a mournful warning against that which can’t be avoided and a cry to help the hopeless, a harrowing lesson of woe as suitable for telling around campfires as in theaters around Herald Square. According to press materials, Fugard has called it "the most important play I've ever written."

Gravedigger Hanabe (Adolphus Ward) is not waiting for anything as ill-defined as Godot, however. He is merely waiting for death, eventually his own, but to earn his living in the meantime, he waits for death to bring the next unidentifiable black villager to his cemetery for the nameless. As the play begins, however, it is the haunted Roelf Visagie (Morlan Higgins) who arrives. He will blow in and out of Hanabe’s life in the play’s single, 90-minute act, somehow managing to leave it even more barren than it had been.

Falling in line with a theme we have tied in Rabbit Hole and The Happy Ones, Visagie, the title character, is reeling in the aftermath of having accidentally hit someone who wandered into the path of his train. The twist here is that his victim wanted to die, and in her final seconds, locked eyes with Visagie.

As tragic as that is, Fugard manages to make it worse: strapped on the woman's back is an infant whose terrified eyes also meet Visagie’s helpless stare. A mother murdering her child splits the emotional atom. And, in the same way energy is never destroyed, only transferred, the emptiness that drove her to the tracks has moved into Visagie. He arrives at the cemetery in hopes Hanabe can identify her grave, over which he can return the pain in a vomited stream of profanity. While he can eventually forgive her, ridding himself of his burden will take another wrenching twist of fate.

Higgins and Ward do fine work in their roles. Vocally, credit to JB Blanc’s dialect coaching, they sound convincing, and they bring the right physicality to each character – the solid, white middle class Visagie and the poor, thin black African. Fugard gives Higgins a particularly long monologue, which he handles well, and Ward earns complementary compliments for keeping up his energy for the long listen.

The design team’s Jeff McLaughlin and Dana Rebecca Woods create properly forlorn set and costumes, respectively, and Ken Booth excels in making the most of modest resources to satisfy a demanding lighting assignment.

This is a triumph for Fugard and a big feather for the Fountain, which Fugard has called, again according to press materials, his American home. It follows its Cape Town premiere, where it christened a new theater named for the playwright. Next week a Long Wharf production starring Harry Groener and Anthony Chisholm introduces the play to the East Coast.

It is a solemn, melancholy piece, adding another two-man, black-and-white drama to Fugard's long list of plays. Perhaps its biggest statement comes in a sly moment to which Sachs wisely avoids drawing much attention. When Visagie arrives, despite the hopelessness he has absorbed, he has not thought to question his faith. In fact, though it appears to be concern for décor as much as for piety, he objects to the way Hanabe has scattered junk on the graves to keep the dogs from digging up the bodies. He replaces the scrap metal with stones arranged into crosses. Eventually, however, without much fanfare, he will accede to Hanabe’s safeguard. Clearly we must take our protection into our own hands.

top of page

THE TRAIN DRIVER

by ATHOL FUGARD

directed by STEPHEN SACHS

FOUNTAIN THEATRE

October 15 – December 12, 2010

(Opened, Rev’d 10/16)

CAST Morlan Higgins, Adolphus Ward

PRODUCTION Jeff McLaughlin, set; Dana Rebecca Woods, costumes; Ken Booth, lights; David B. Marling, sound; JB Blanc, dialects; Elna Kordijan, stage management

HISTORY The Train Driver received its world premiere at The Fugard Theatre in Cape Town, South Africa in March 2010. U.S. Premiere

Adolphus Ward and Morlan Higgins

Ed Krieger

Move on up

Few frequent the bar in Kristoffer Diaz’s Welcome to Arroyo’s, now receiving its West Coast premiere at the Old Globe (through October 31). That will change. The place – and the play – are a meeting ground where old values and new ideas can make the most of each other. And, most importantly, everyone can have the time of their lives.

Director Jaime Casteñeda matches Diaz’ vision with a staging so tight and effective that it achieves the feel of loose spontaneity. His cast of six touches all the bases –comedy, drama, pain, romance, music, and the same sense of fun that packs Diaz’ dialogue to the point of bursting.

Clearly designed for a new generation of theatergoers who might be drawn to a play that celebrates the traditions of Hip Hop culture – which, it reminds us, is entering its fourth decade – it is just as exciting for those seeking encouragement about theater's future. Although the pre-show music may be just the kind of repetitive pounding that requires open containers and dance floors, all the music in the show is uplifting, whether it's sampling current artists or past figures like Marsalis and Mayfield.

Diaz weaves several story strands together with admirable economy. Arroyo (Andres Munar) has opened a bar on the ground floor of the building he and his sister Amalia, "Molly," (Amirah Vann) inherited from their recently deceased mother. Molly is an 18-year-old with a fearsome temper and a chip on her shoulder apparently made of flint and ready to ignite at the slightest scratch. She is a born artist whose canvas is the city’s buildings.

Mrs. Arroyo’s deli, or bodega, on New York’s Lower East Side made her a beloved neighborhood figure. That spirit inspired Alejandro to create a "community center for adults, with alcohol," The two locals he hired to help make renovations stayed on to provide Hip Hop entertainment for the patrons and a comic Greek chorus for the play. Nelson "Nellie Nell" Cardenal (GQ) and Trip Goldstein (Wade Allain-Marcus) have ambitions to rock the Hip Hop world as The Trip and Nell Cartel.

The play begins with the appearance of the first of two outsiders. Lelly Santiago (Tala Ashe) is a Hip Hop acolyte out to make a name for herself by elevating the role of women in the art form. She has a photograph of Hip Hop’s one pioneering woman, who disappeared after achieving local fame 30 years before. She believes "Reina Rae" was Alejandro’s mother.

The other stranger is Officer Derek (Byron Bronson), who experiences a powerful mutual attraction with Molly when he apprehends her for tagging. While he strives to be a good cop who provides a valuable community service, he longs to pick up a camera again and pursue his photography.

This mix of optimism and desire to strive gives Arroyo’s its lift, while the realities and rejection all the characters experience gives it tension. Castenada’s excellent cast – as comfortable and generous in their roles as actors in a successful road company of Rent – keep things energized. The arena-configured Sheryl and Harvey White Theatre facilitates the play's mission to break the fourth wall by not having any of the other three. Walls between scenes, characters, styles and time periods are also ignored, especially by Trip and Nell, but also by Lelly, who is the character we follow into the play.

Takeshi Kata’s set, Charlotte Devaux’ costumes, Matthew Richards’ lights, and Aaron Rhyne’s projections of urban art by Writerz Bloc create a simple but colorful physical space that gets added dimension from Shammy Dee’s music and Paul Peterson’s sound cues.

If there’s any fault to Diaz’ structure, it’s that every character has artistic talent and appreciation and strives to greatness with youthful exuberance. However, Diaz' playfulness allows a fable aspect. And, the play, like its characters is so full of talent, appreciation and youthful exuberance, that it provides exciting evidence that theater is going somewhere. And, with Diaz’ second play achieveing a "Pulitzer Prize nomination," we’ll surely be meeting up with him again soon.

top of page

WELCOME TO ARROYO’S

by KRISTOFFER DIAZ

directed by JAIME CASTANEDA

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

September 25-October 31, 2010

(Opened 9/30, Rev’d 10/2m)

CAST Wade Allain-Marcus, GQ, Tala Ashe, Andres Munar, Amirah Vann, Byron Bronson; u/s Bayardo De Murguia, Xochitl Romero

PRODUCTION Takesi Kata, set; Charlotte Devaux, costumes; Matthew Richards, lights; Paul Peterson, sound; Aaron Rhyne, projections; Writerz Blok, urban art; Shammy Dee, music director; Elizabeth Lohr, stage management

HISTORY Developed at South Coast Repertory, Lark Play Development Center’s Playwrights Week, and BareBones at the Lark, in partnership with Hip-Hop Theatre Festival; premiered at American Theatre Company (Chicago) West Coast Premiere