MARK RUCKER'S CURTAIN CALL

A group portrait of the brilliant theater director who recast bow-taking

by CRISTOFER GROSS

PROLOGUE

Sunday, January 10, 2016 in New York City was 20 degrees warmer than it had been the days before, or would be in the days that followed. There was also unusual warmth among the late matinee audience at the Alice Griffin Jewel Box Theatre, who cheerfully, tearfully embraced as family.

They had come to Pershing Square, not for a performance but to join in the third memorial in as many months for director Mark Rucker, who had died in his San Francisco home the previous August 25. Colleagues at New Haven's Yale Repertory Theatre and Yale School of Drama, where 23 years earlier Rucker earned his MFA in Directing, had organized the tribute. Based primarily in Los Angeles and Orange County, where he had been born, raised and earned his bachelor's at UCLA, Rucker had quickly ascended through America's regional theater network, working at major theaters across the country. He became one of a handful of Associate Artists at Orange County's South Coast Repertory and in 2010 accepted the position of Associate Artistic Director at San Francisco's American Conservatory Theater.

Over a three-decade professional career cut short at age 56 he had earned his share of awards and critical acclaim. By both enlivening and illuminating the classic texts of Shakespeare and others with a calculated but seemingly carefree infusion of contemporary cultural references, he had helped refresh theater and win back audiences in an era when they were losing interest.

His impact was even more profound backstage, with actors, directors, dramaturgs, designers, techies and administrative staff, and most enduringly with playwrights, who found in him both collaborator and champion.

"His life was a series of overlapping circles, and he had profound intimacies within those circles," said Michael Edwards, Artistic Director of Asolo Repertory Theatre. Edwards met Rucker at UCLA in 1979, was his first serious relationship, and remained among his closest friends.

"Some of us were in more than one circle, but we each felt that we were involved in some central way in his intimate life," he said. "He was the treasured intimate person, the one who had a profound impact on the rest, and that became clear at the three memorials."

SCR and ACT held their memorials in November. Both ACT and San Francisco's Magic Theater dedicated their 2015-16 Seasons to Rucker. Now, his East Coast friends were coming together, nervously, numbly, like rings around a missing peg. As the program wove from heartfelt tribute to hilarious anecdote, the hollowing grief left by his mysterious accidental death made way for a more welcome sense of wonder: How had he become so singular a figure in virtually every life he embraced?

ACT 1, SC. 1 | THE CITY BARBER

The Great Depression was at its worst in 1932, when the Gross National Product began a two-year fall of 13.4 percent and unemployment reached 23.6 percent in that year alone. For the poverty-stricken families of Elmer Bruce and Leona Belle Rucker in Warrensburg, Missouri, and Ford and Ida Mae Forbes in Foxworth, Mississippi, even escape into the movies was a luxury.

Still, into the shared hardship of that year, the Ruckers welcomed Lester Benton Rucker on May 21 and six weeks later the Forbes of Foxworth did likewise for baby Norma. In December the Ruckers joined the dusty exodus to Los Angeles, settling southeast of downtown in Bell Gardens. A dozen years later, the Forbes did the same. Lester and Norma would meet in junior high school and date exclusively through high school. He was the first man she ever kissed and upon graduation she insisted they marry. She was prepared for his response, that they had no money, and quickly brandished the large roll of secretary earnings she’d hidden in her purse. Impressed but still cautious, he scratched his jaw. “But you’re not 18.”

“So we’ll drive to Nevada,” she said, ending the discussion and putting them on the road to Las Vegas. Arriving after dark they woke a justice of the peace, married in a civil ceremony hours before she turned 18, and were back in Southern California in time to go beach fishing as the sun came up.

They moved to neighboring Huntington Park to start their family, adding Michael Benton in April 1952, Mark Henry on December 30, 1958, and Leslie Lorraine in June 1960. In the mid-Sixties they moved to Orange County, staying a year in Santa Ana while saving to buy in Newport Beach.

“Coming from nothing, with dirt poor parents, my folks did everything they could so we could go to nice schools,” Leslie Rucker said. “Father did some technical editing, but then went to barber college and eventually owned shops in five cities with the name City Barber.”

Norma was the barber’s bookkeeper and Brinks driver, making the cash-collecting rounds to each location with the kids in the backseat. Mark, a huge reader, likely had a book in his lap.

“His interest in theater probably began around the age of 5,” Norma said. “He would lead the neighborhood kids in little plays.” Theater was always his ambition, Leslie added. “It was never a question there was anything else.”

The Newport years began in the Lido Sands community, minutes from the Pacific. With “another brainiac,” Rucker adapted children’s books like The Crying Witch and The Mad Scientists’ Club series into plays he, Leslie, and their friends performed for parents and neighbors. When middle school teachers used LIFE Magazine’s “Miscellany” page and other curious photographs to inspire creative writing, “Mark came up with these amazing, completely bizarre stories that we’d also make into little plays.”

In the 1970s, Lester sold all but the shop on Newport Pier, located beside a popular jazz dive called Sid’s Blue Beet.

“He was very much an artist at heart,” Leslie said of her father. “I have a beautiful drawing he sketched of my mom’s grandmother’s house in Mississippi and another of my mom resting on a couch. And he loved movies. His barbershop was wall-to-wall posters and actor photos, and we would stay up late with him to watch movies. Our favorite was Stage Door.

“But he was a man of the ’50s who was going to make money for his family,” she said. Over the years, except peeking into a high school production of Pippin that his second son directed and daughter choreographed, the elder Rucker never attended anything created by his children.

“He just wasn’t social and didn’t get out,” Leslie explained. “But I also think that Mark’s life and talent were a complete mystery to him. Well into Mark’s career he shyly asked me, ‘What does a director do?’ Rather than going to Mark. I just think that, because he wasn’t terribly educated, in his mind Mark was so much more than he could grasp.”

|||

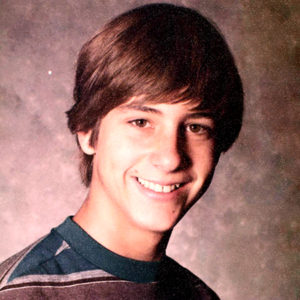

In 1973, a Newport Harbor High School freshman interested in theater was fortunate to have Tom Bradac as his drama teacher. But two years later, Bradac would leave, eventually founding Shakespeare Orange County. He remembers that Rucker “was fully involved in various productions, sharing the stage with Lauren Mitchell, who would become a Broadway producer, including Jersey Boys, and Kelly McGillis of Top Gun fame. He was obviously a talented young man in company with many talented kids.”

It was during high school that Rucker came to terms with his sexuality. Years later, with typical lightheartedness, he told Playwright Annie Weisman Macomber about the awakening.

”I remember asking when he realized he was gay,” Weisman Macomber said. “And he told me he remembered feeling different when he used to sit in class and his doodles were Liza [Minnelli] eyes. He would work to get them just right, drawing all the layers of eye shadow and the long lashes. And,” she laughed, “I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s pretty clear.’”

After Bradac left, overseeing student productions fell to Joe Swift, a designer by training who would lean on Rucker for ideas. Before long, Rucker just directed by himself, sometimes also playing the lead: Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls, Albert in Bye Bye Birdie, and Jesus in Godspell.”

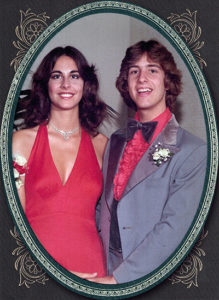

“He was handsome, quiet and very talented,” recalled Diane King Vann, who was Newport Harbor’s musical and choir accompanist, then musical directed as Rucker took over directing his own productions.

“I was only five years older than the students and bonded with a small group of the Drama/Music weirdos,” she said. “He asked me to be his date for the Prom and though a small group of us went together, I was his official date. He bought me a corsage and everything. He hadn’t come out yet, but we kind of knew that was going to happen once he got to college.”

ACT 1, SC. 2 | THE CITY STAGE

In 1978, UCLA’s theater department was still within the College of Fine Arts. The School of Theater, Film and Television would come in 1990. Its faculty of working artists spanned the field, from young, incoming Beverly Robinson, who “ushered in a climate of intercultural exchange with her African American Theater History course,” to Michael Gordon, a veteran of the Group Theatre and director of the original Jose Ferrer Cyrano.

This was the world that awaited incoming freshman Mark Rucker.

“The department was on fire,” Edwards said. “We got connected to the great American tradition while we were there and they made us feel like we could do anything. Mark was one of those who made an impact as an undergrad at UCLA.”

He and Julie Bernatz, a classmate from Newport Harbor who wasn’t attending UCLA, shared a Westwood apartment. During the first semester he hosted a study group for a theater history exam.

“The apartment was like a set from a 1930s play,” Deena Gornick recalled from her London home, where she is an international corporate coach. “It was eye-popping: fabulous mirror-framed pictures of flamingoes and those liver-shaped tables. I [arrived] carrying a big coat and all these bags of food and books and, feeling the nervous 19-year-old, began play-acting that I was Helga, the bag lady! Mark was dazzled: It was instant friendship. I was stunned by his quips. I hadn’t experienced such wit from my peers.”

Bernatz would move on and Gornick and Rucker would move into an apartment on Holman Avenue, adding Martha French as a rent-paying roomie. After freshman year, Lester and Norma took Leslie and Mark to England and Europe for the summer of ’79. They saw three Shakespeare productions in Stratford-upon-Avon and three West End shows: Tom Stoppard’s Night and Day with Maggie Smith; Evita; and The Gin Game with Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy. Rucker recorded the entire adventure in an eclectic journal.

With Rucker on a family globe-trot and French off to study in France, Gornick brought in a new renter with the proviso that, “because the beautiful furniture was Mark’s, he must approve any new roommate.”

Nine years their senior, Edwards was a Master of Fine Arts student with professional experience directing opera in Australia.

“Mark was so compliant that he agreed to Michael right away,” Gornick said. “I think Mark, like me, was dazzled by Michael’s experience and acumen. But Michael was just as enamored with the style that Mark had and basically they fell in love and they began a relationship that was as artistic as it was passionate. They really grew from each other.”

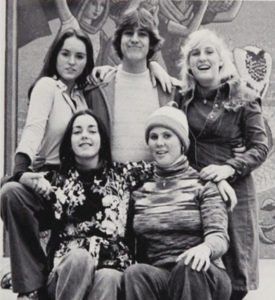

While performing in a production of A Taste of Honey, Gornick became friends with lighting designer Pat Morrison, who became the fourth roommate and “we had this formidable house called Holman House,” Gornick said. “It was just wild.”

“I think the entire theater department ended up coming to parties at our house,” Edwards added, “which entirely owed its look and style to Mark.”

One student who became part of the “extended Holman House family” was Patrick Stretch, a UCLA theater major from San Francisco who was a couple years behind them. Rucker directed him in a scene from Jean Genet’s The Maids for an AP Director’s course taught by Michael McLain, and they “became very good friends.”

“There weren’t a lot of university students whose apartment walls were lined with academic treatises on theater and gay politics, and opera blasting,” Gornick added. “Michael would take the needle off the vinyl to tell you exactly what was going on in the aria at that point. ‘Listen to the psychological depth of the music,’ he’d tell us. Although I had a marvelous education at UCLA, I probably learned as much if not more living in Holman House, all while listening to opera, shaking up martinis, and cooking real food!”

As exciting as the residence proved to be, Rucker’s focus was always on theater. One of his notable efforts was an extra-curricular staging of Wendy Wasserstein’s Uncommon Women and Others in a found space in Royce Hall.

“It drew students from all over and that’s when we knew Mark had the drive,” Edwards said. “He had it.”

When Leslie was invited up to Holman House for a weekend, she was intrigued by a photograph of her brother and Edwards with an odd caption that asked, What’s wrong with this picture? “In my head I went, ‘Nothing.’ But then I said, ‘Mark are you gay? Are you with Michael?’ And he said ‘Yeah.’”

Some years later, when Leslie was going to college in San Francisco and her brother was now openly gay and living in Los Angeles, he asked her help.

“It was now the mid-Eighties,” she said, “and he just felt like my mom should finally know. But he asked me to be the one to tell her because he didn’t have a clue how she would react and was so worried she would be hurt and he couldn’t face that.”

The next time Norma visited San Francisco, Leslie took her to the theater.

“I asked my mom to see La Cage aux Folles and we went out to dinner after and I told her. She said she had no idea, but later on in the conversation she said she had known.”

Norma would be the one to tell Lester, who accepted it without a show of emotion, asking only that it “not become dinnertime conversation.” He would quickly soften, however, and welcome Rucker’s long-term partners into the family, sharing holiday trips, mourning with him when one broke Mark’s heart, and sharing the excitement when another agreed to marry him.

“For a man of his generation,” said Leslie, “he did a stellar job.”

|||

In 1982, Rucker and Edwards graduated. Gornick had taken time off to start working professionally, appearing in, among other productions, The Old Globe’s Sorrows of Stephen that year. They had moved from Holman Avenue in Westwood to Norton Avenue in West Hollywood, and a beautiful, Spanish-style classic Hollywood home that became Norton House.

“It was built in the 1930s by a Hollywood cinematographer,” Gornick said, “a fabulous old house complete with a darkroom in which Mark taught himself to develop his own photos.”

Dedicated to continuing to learn and advance their art, they asked Edwards to run acting workshops. He agreed and they rented a tiny studio on Gardner, between Sunset and Hollywood, which became Gardner Stage. Edwards held three workshops each week with ex-students and their friends from UCLA paying around $25 a month. They made room for an audience of 40 and before long had staged productions of Michael Weller’s Moonchildren, Romeo and Juliet and others. Edwards and Rucker, now no longer romantic partners, were co-directors.

Around this time Morrison, who was stage managing Spalding Gray’s Interviewing the Audience, got tickets for Gornick to attend almost every performance. The following week, Rucker’s Valentine’s Day gift to her was a triple bill of Carmen Miranda movies.

“I was sitting through those movies still buzzing from seeing Spalding Gray,” Gornick said. “After the movies we drove downtown and saw a loft for rent on 5th and San Pedro. I said, ‘We gotta move here!’ The next day we told the Gardner Stage group we were moving.”

“They said we need to move downtown,” recalled Edwards, who had just been hired to teach at UC Santa Cruz. “Downtown is where it’s going to be happening, they said.”

“We called ourselves City Stage,” Gornick continued. “Everybody in the company, which was our gang from UCLA, were asked to create their own one-person show, and we distilled them into our opening production, inspired by Spalding Gray, called Woman with the Stomach of Steel and other stories. That was late 1982.”

City Stage would continue for several more years, but during those summers, Rucker would join Edwards on the UC Santa Cruz campus, where a new company dedicated to Shakespeare would provide each of them his launchpad.