HISTORIES

Hobnobbing with Obsession

A chronicle of my immersion into Sondheim's 'Sweeney Todd' and

and a healing luncheon with the show's star, George Hearn.

by Cristofer Gross, from AirCal Magazine, June 1981

This is not a review: it's an exorcism. A year ago, through the original cast album of 1979's Best Musical, I began to be possessed by a demon. The musical is Sweeney Todd and it will open this month in Los Angeles, the last city in the first-run tour, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. I had listened to the recordings of the great musicals as a youth and still knew many by heart, but I had never heard anything like this before. Not only is there a massive amount of music (almost two hours on the recording), but it is woven like a classical composition: melodies blend into recurring themes, and new themes give way to variations. The massive amount of lyrics leaves the realm of musical theater and enters the area of literature. All this worked on me until I was completely obsessed.

The symptoms were at first subtle. I'd drop lines from the show's lyrics into conversation. After reading Herb Caen's column that Sweeney Todd was doing poorly in San Francisco, and would be closing early, I got nervous. Using a line from the play, I cried, "There is a higher power to warn me thus in time!" and began my crusade. I told friends that they owed it to themselves to see and hear the show. My final act, I decided would be to confess my possession in print, hoping to spread word of the magnitude and power of the production. This might encourage a few more to investigate the music.

I soon discovered that a proper exorcism of this kind would mean working my way through research into the living theater and finally to the dark heart of my obsession – to face whatever demon was there.

I researched the legend, the composer, the period. Read the play, the book, and finally saw the performance. During this time I found more and more subtleties in the recording. Finally, I decided, the day would come when I would face Sweeney Todd.

I guess that demons are prowling everywhere, and some attach themselves to all of us. I don't know which ride with Stephen Sondheim, the show's composer, lyricist, and guiding mind. As a youth, with his parents divorced, he spent a great deal of time at the home of family friend Oscar Hammerstein II. Hammerstein wrote the lyrics for Oklahoma and many others. But it was Oklahoma that is marked as a turning point for musical theater because the lyrics moved the story line and developed characters. When young Stephen expressed interest in Broadway and showed developing talent, Hammerstein tutored him. Since then he has been surrounded with the best of Broadway, and has been responsible for changing musical theater almost as much as his mentor. Some would say more.

He was lyricist for West Side story (music by Leonard Bernstein), and Gypsy (music by Jule Styne). He wrote and composed Anyone Can Whistle, A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum, Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, and Pacific Overtures. He has worked with a group headed by Hal Prince, whose credits are too numerous to list; orchestrator Jonathan Tunick; and Angela Lansbury who, thanks to Sondheim, has become the first lady of the musical stage.

It was in London in the 1973, during the revival of Gypsy, that Sondheim and his demons met fellow spirit Sweeney Todd. There, in Playwright Christopher Bond's version of a 100-year-old legend, was contained the angriest character in Anglo lore.

Sweeney Todd, nee Benjamin Barker, is a man sentenced to a life term in an Australian prison by a judge who wants Barker's wife. He returns to London with a new identity after 15 years to find his wife has taken poison, apparently as a result of the judge's cruelty. He also finds that his daughter, now a beautiful woman, has become the judge's ward. Teamed with a pie-maker who is landlady of his old barber shop, he vows revenge. His plan is to get the judge in his barber chair and repay the injustice served him when he sat in he judge's docket.

So it was that Sondheim came back to America with this story to make a musical of. He had found the perfect accomplice for unleashing demons, and a formidable challenge for a musical composer obsessed by games, puzzles, and anagrams. (The play Sleuth is said to be inspired by Sondheim, and the movie, The Last of Shiela is written by him.)

Six years later the thing was done.

In 1979, Sondheim, Prince, Hugh Wheeler (book), Tunick, Lansbury, Len Cariou (Sweeney) and a talented group of artists opened Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street on Broadway. "Brilliant," said many. "Ghastly," said many. "But flawed," said critics. And many stayed away. Six years of embroidering a show, 90 percent music, that only a games player could conceive, and the response was cool. Some said that Sondheim only writes for a few highbrow friends anyway. He doesn't care if the public likes it.

"That's not true," says Betsy Joslyn, the beauty who plays Sweeney's daughter. "He wants everyone to like it, to like him. And he's truly surprised when his shows aren't thought to be geared to everyone." But he is a consummate craftsman, a perfectionist pie-maker – he has to forge ahead, look instead to the frontiers he's covered, not the gaping middle ground that is the territory of others.

Richard Eder of The New York Times wrote in his column on the morning after the play opened: "The musical accomplishments and dramatic achievements of Stephen Sondheim's black and bloody Sweeney Todd, are so numerous, so clamorous that they trample and jam each other in that invisible but finite doorway that connects a stage and its audience: doing themselves some harm in the process … It is necessary to give the dimensions of the event. There is more artistic energy, creative personality and plain excitement in Sweeney than in a dozen musicals."

A SAN FRANCISCAN SUMMIT

I made it to San Francisco for the last performance. The play was full of energy. A friend who had known nothing about it saw it too and loved it. The next day, full of confidence I made my way to meet Sweeney face to face. With some trouble I found Julius Castle on Telegraph Hill, where I had been told to meet him. Walking down the stairs from Coit Tower I made my way, out of breath, into the restaurant and waited.

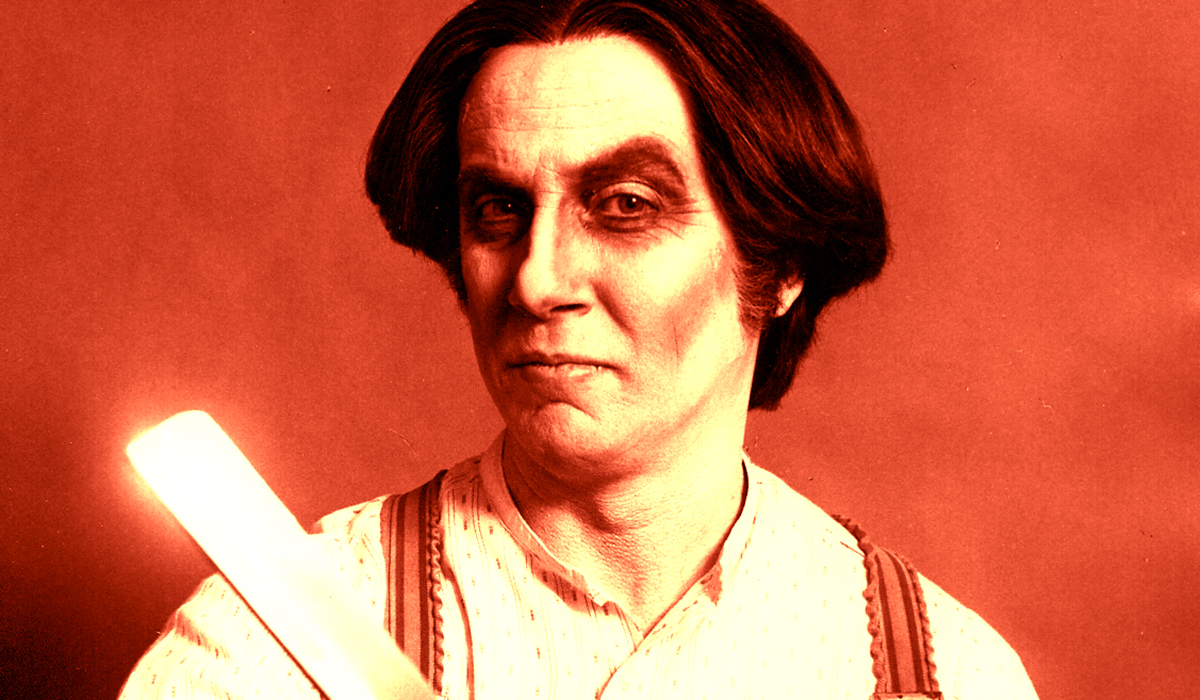

In he came. His current embodiment is actor George Hearn, who took over for original cast member Cariou after the first year.

George Hearn is a far cry from his demonic alter ego. He looks more the turf accountant from Cork, though the cork of his youth was used to fish the Mississippi near his native St. Louis. We got along immediately as two possessed of the same spirit will. He described how he got involved with Sweeney.

"Somehow," he began, with the crispness and economy of one whose speech is his livelihood, "I was visible at that moment, and the right people had seen and heard me. I guess I've done a little over 100 plays since joining Equity. Mostly I had not done musicals (1776 and I Remember Mama two notable exceptions). For years I didn't do musicals at all. Just gave up on it. I started out wanting to be an opera singer. But I gave that up. I love words but I get disappointed in lyrics. In opera it was that over-dark, mushy sound.

"In fact, I said to Stephen when he called me at home to tell me how much he liked me in the part, 'Stephen, I just want to tell you I think you're the reason I didn't go into opera, and why I haven't found my métier. It's that I love words, and I've never found a composer who has the passion for language that you have and insists on it being there.'"

I felt my eyebrow raise as passion begin disorienting George's speech.

"When I was studying opera my voice would get darker and darker and I felt, that's not what I want – I want to talk language. That's why I like doing Shakespeare. I love language; so loving language and music together makes you pronounce words in a way that opera singers don't – it's trying to balance those two things. And after Gilbert and Sullivan, who were geniuses at the marriage of words and music, I don't know anyone who's even attempted it besides Stephen.

"And he apparently agonizes over words, always looking for the perfect choice. During rehearsals he ran in one day and said, 'I've got it, I've got it, I am sir, entirely at your disposal' (a line Sweeney says before attending to a doomed customer) and he fell about. He'd been up all night, up thinking about it for weeks in fact, the exact word for that moment. God, it's so, rich … That's what makes this piece so hard, crystalline – the constant meaning of every phrase. He stands so completely alone to me, and I think the whole face of the theater will be changed because of this piece, certainly musical theater. It's going to affect everything …"

I sat listening to George, my fellow possessed: His demon revealed. And I realized it's not by Sweeney we have been run ragged. I had found Sweeney and found him the mask for something larger, something living. Sondheim himself. And with his next projects, Kaufman and Hart's Merrily We Roll Along, then Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard, I'll be happily possessed for years.

George and I parted. He to fish, then back to Sweeney in Los Angeles. I to this review and researching Sondheim. After all this, my research led me to one interesting coincidence in the March 19, 1973 issue of Time. The article ended with mention of Cutthroat Anagrams:

"Says Sondheim: 'You don't take turns. You just turn up letters, and the first person to see a word yells it out. Lennie Bernstein is a terrific anagram player. All during the work on West Side Story we would blow up our tensions at the anagram table.'.

"Since Sondheim is obviously a happily possessed man, what might the letters of his name spell out in such a game? Voila! 'His demon.'"

PHOTOS: George Hearn as Sweeney Todd in a 1980 publicity photo by Martha Swope (top); with Lansbury (middle inset); and George Hearn during "Wall to Wall Sondheim" at Symphony Space in New York (Debra L Rothenberg)

RELATED STORIES