APRIL 2007

Click title to jump to review

ASSASSINS by Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman | Meta Theatre

GREATER TUNA by Jaston Williams, Joe Sears and Ed Howard | La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

MASTER OF THE HOUSE by Shmuel Hasfari | Laguna Playhouse

MY WANDERING BOY by Julie Marie Myatt | South Coast Repertory

SYSTEM WONDERLAND by David Wiener | South Coast Repertory

WOMEN OF LOCERBIE by Deborah Brevoort | Actors' Gang

A little nut music

The vaporous America dream is often distilled into motivational bromides. They inspire the best in some and the worst in others. The one that defines this as a country where anyone can grow up to become President just underscores how far removed from power some feel. In Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman's Assassins, currently a Sight Unseen Theatre Company production at L.A.'s Meta Theatre through May 20, the composer-lyricist and his Pacific Overtures book-writer explore nine lowly Americans who sought to – and in four cases did – overpower the man who embodied this aspect of the American dream.

The 60-seat Meta provides an appropriately claustrophobic environment in which to meet Sondheim's assassins. The wonderful cast, under brisk direction by Cindy Jenkins and the musical stewardship of Andy Mitton and Nancy Dobbs Owen, creates two required dimensions: that these be loners and that they form a strange historical collective. Both chronologically and artistically, the obvious starting point is John Wilkes Booth (Michael Laurino), the actor who killed Abraham Lincoln in a theater. From Booth to John Hinkley (Lance Kramer), the actors connect these misfits to their era, to their bizarre motivations and to each other.

Assassins is a black comedy clubhouse the way the Righteous Brothers' "Rock and Roll Heaven" is a Top 40 gathering spot for deceased pop stars. A Balladeer (the outstanding Kyle Nudo) and a "Proprietor" (Patrick Seitz, prone to mugging) alternate major domo functions to introduce and interact with the would-be executioners. In addition to Booth and Hinkley there are Charles Giteau (Philip D'Amore), who killed James A. Garfield; Leon Czolgosz (Jason Decker), who killed William McKinley; Guiseppe Zangara (Salvatore Vassallo), who attempted to kill FDR, but killed the Mayor of Chicago beside him; Samuel Byck (Corey Pepper), who plotted to kill Richard Nixon; Sara Jane Moore (Gina Torrecilla) and Lynette Fromme (Juliana Johnson), who attempted to shoot Gerald Ford; and Lee Harvey Oswald (James Sheldon), who killed JFK.

Ms. Jenkins guides the big musical into the small space so that ensemble numbers fit as comfortably as the important two-actor scenes. Three of these two-handers are particularly noteworthy. Rachel Payne as Emma Goldman and Mr. Decker as Czolgosz carve out lovely emotional space for the anarchist author to innocently encourage her acolyte's actions, creating that imagined meeting and setting up Hinkley's similarly inspired but utterly apolitical shot a century later. Mr. Laurino and Mr. Sheldon also connected beautifully for the imagined brainwashing of America's last successful assassin by its first. And, the delightful Ms. Johnson and Ms. Torrecilla provide comic relief without sacrificing their characters' convictions. (Agent alert: The program bio says that the Witherspoonesque Ms. Johnson needs representation.) Mr. Kramer's Hinkley is always engaging, as are the two ensemble players, Rachel Jendrezejewski and Joaquin Nunez.

Only demerits at this performance were in the Gordian knot that tied the canvas strap to Oswald's rifle (kudos to Mr. Sheldon for not missing a bead) and the lighting cue for Byck's second solo scene. Perhaps the actor missed his spike. If not, there's just too much shadow from the car door. On the subject of Byck, Mr. Pepper benefits from comedic gifts, but they occasionally push his character past definition.

Sondheim does not intend to explain the assassination phenomenon as much as lay it out with a unifying principle of theatricality. As is his wont, his music here has a thematic tie-in, sounding the music of each historical era. Though such nuance would be better served by a full orchestra, the five musicians on stage evoke the styles and promote the essential sense of smallness and withdrawal that fits these characters. Still, as is happily the case with Sondheim, one hears him in his music as well: a hint of Pirelli in "How I Saved Roosevelt," ensemble cadences from Company or Sweeney in the final "Everybody's Got the Right."

As is also often the case with Sondheim productions (even the merely average), they will sell out. With one this good, to paraphrase the pop song about fallen leaders, "just look around and it's gone."

(For the record, this production returns to the original Broadway song list, omitting the subsequently added "Something Just Broke," the roundelay of people recalling where they were when they heard JFK had died. There is also an added in coda from that horrific weekend in 1963.)

ON THE REAL SIDE: Seeing Assassins four days after the worst mass murder on a U.S. campus, connections were inevitable. During the week, commentators tried to sort out the killer's personal alienation and possible motives from the messages – both intentional and inadvertent – that he left behind. Other commentators – a man on PBS's NewsHour and a woman at a political rally aired on C-SPAN – leaned this tragic loss of 32 citizens as a yardstick against the casualty figures from Iraq, where such loss is a daily occurrence. Was that meant to dilute the grief of Americans across the country? Quite the contrary. It is to remind Americans of the impact those deaths should be having there and here.

Postscript. After writing about these connections between assassinations and school shootings, I sat down to a "60 Minutes" lead-off piece about the connection between assassinations and school shootings. Apparently studies are ongoing that the same forms of alienation that drive Presidential assassins drive the loners who kill their fellow students.

top of page

ASSASSINS

music and lyrics by STEPHEN SONDHEIM

book by JOHN WEIDMAN

musical direction by ANDY MITTON

directed by CINDY JENKINS

SIGHT UNSEEN THEATRE

/ META THEATRE

April 20-May 20, 2007

(Reviewed 4/20)

CAST Kyle Nudo, Michael Laurino, Philip DíAmore, Jason Decker, Salvatore Vassallo, Corey Pepper, Juliana Johnson, Gina Torrecilla, Lance Kramer, James Sheldon, Patrick Seitz, Rachel Payne, Rachel Jendrezejewski, Joaquin Nunez

MUSICIANS Andy Mitton, keyboards/conductor; Clark Freeman, percussion; Sheila Gonzalez, winds; Brian Bunker, strings; Daren Burns/Ruben Ramos, bass

PRODUCTION Dan Jenkins/Sam Roberts, set/lights; Valerie Rothenberg, costumes; Ellen Juhlin, sound; Nancy Dobbs Owen, musical staging; Casey Clark, stage management/fights

Philip D'Amore

Ed Krieger

Fish stories

For anyone with a soft spot for the history of American show business and especially the years of practiced Vaudevillians, the theatrical team of Jaston Williams and Joe Sears, purveying their shtick in Greater Tuna at the La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts through April 29, will warm the heart as it looses the laughs. Legend has it that Greater Tuna began in 1981 when its three creators –Williams, Sears and director Ed Howard – began ad-libbing on a political cartoon at a party. In a couple of years they had a long-running Off Broadway hit. The show would spin off two sequels, merit an HBO taping with Norman Lear directing, and earn a command performance at the White House and an overseas run.

After more than 25 years, Sears and Williams give no indication that they are running out of gas or need their timing adjusted. If they are aging further out of the youngest roles, it's only to slide more gracefully into the older ones. The quick changes never snag, allowing a seamless flow of 20 odd characters with names like Arles Struvie, Petey Fisk, Phinas Blye, R.R. Snavely and Thurston Wheelis to introduce another generation to "the third smallest town in Texas."

The show roughly follows one day in the life of Greater Tuna as experienced by its most colorful citizens. From sign-on to sign-off at the local radio station, we eavesdrop on men and women, boys and girls and the pious and profane.

Every character gets special care to appear both real and real funny. The smaller Williams provides the most range, playing all the children and a diversity of adults. The larger Sears, however, reveals himself as a master comedic actor. Most impressive are two matrons who Sears keeps rooted in character. His Bertha Bumille and Aunt Pearl Burras are all the more hilarious because of the naturalness Sears brings to them. These are not camp female impersonations or exaggerations like Monty Python's bedraggled biddies. This is just good acting. A century ago these stage personas would have ranked him with Fields, Lahr, Wynn, and of course Oliver Hardy, whom he recalls without ever imitating.

In a world now familiar more with the humor of Jeff Foxworthy and Larry the Cable Guy and the gloss of New Country music, and less with the authentic corn of "Hee Haw" and Minnie Pearl, this script may seem a bit dated. It also hints that there will be some bigger pay off from the various storylines that are vaguely followed during the two-hour, two-act performance. However, it does not add up to more than a lot of vignettes.

The flirtation with the wholly unfunny world of racism and high school censorship, coming through the mouths of people we are ready to embrace, makes for some discomfort. Nevertheless, these two performers keep it light and funny. They are masters of an important slice of stage comedy. A quarter century out of the can, this Tuna retains its freshness and Williams and Sears their spot in theater history.

top of page

GREATER TUNA

by JASTON WILLIAMS, JOE SEARS

and ED HOWARD

directed by ED HOWARD

LA MIRADA THEATRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS

April 13-29, 2007

(reviewed 4/14)

CAST Joe Sears, Jaston Williams

PRODUCTION Kevin Rupnik, set; Linda Fisher, costumes; Ken Huncovsky, sound; Root Choyce, lights/stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Joe Sears and Jaston Williams

Michael Lamont

House parting

The floor plan that Shmuel Hasfari has laid out for The Master of the House, receiving its American premiere through April 29 at the Laguna Playhouse) covers a lot of ground. Set in Tel Aviv, where its premiere would earn the 2003 Israel Theatre Academy Award for Best Play, it touches on Israel's history, from its 20th Century resurrection to the daily threats to destroy it. But the international politics are merely background for a smaller portrait with more universal resonance. One couple, whose problems will trace in part to political unrest, is at a crossroads from which views of aging, marriage, the safety of our children and the sanity of our parents can be explored. While Richard Stein's staging does not show the script, translated from Hebrew by Anthony Berris, successfully balancing the relative weight of its storylines and themes, one senses a potential for greater power hidden between the lines.

The principal metaphor in The Master of the House is renovation. How to balance the conflicting needs for renewal and for retaining links to the past is the question that underlies all the action and relationships here. That reflects back on the state of Israel, where age-old traditions are in pitched battle with changing realities. But it ís the fragile truce between husband and wife Yoel (Jonathan Goldstein) and Nava (Stacie Chaiken) that is at the center of The Master of the House.

One of the ironies suggested by the play's title is that we think of a household as having one person in charge. Who is in charge of Yoel and Nava's home seems clear at the beginning, but is then up for grabs and ultimately decided under new terms. As is common in many households, these adults are only saying part of what ís on their minds. Yoel does this because he's completely stopped up as a person. Nava does it because his blockage gives her nowhere to go. That passive aggressive standoff results in exchanges that sound like shoot-outs, passing without revealing much. They make the play's action seem more circular than it may in fact be. If Hasfari's multi-level story is going to succeed, as it apparently did in Tel Aviv, it requires the director and central actors to find an underlying logic to drive these two scattered personalities from curtain to curtain call. Here where it should feel heartbreakingly real, it merely feels broken.

Goldstein's Yoel is a scruffy columnist living in the same house he grew up in. He writes about nostalgia and architecture – which reflect his own reverence for old buildings on one hand and clinging to the past on the other. Creating a retreating personality is a tough assignment for an actor: he is the thing he is not. Not surprisingly, it's Yoelís moments outside himself – lost in nostalgia or lightened by drink – in which Goldstein gets to show some of who this man might have been.

Chaiken's Nava is a dream – his dream – come true. A woman Yoel has loved since grade school, Nava is now a beautiful, articulate, successful bread-winner who inexplicably overlooks Yoel's incredible Farbisener routine: he treats her like a waitress, fails to tell her his plans, doesn't notice his father's advancing dementia, doesn't even try to fix the toilet, and on and on and on. That she stays with him may be more understandable in Israel. It's not translating here. That he calls her the love of his life, yet isn't interested in sleeping with her anymore, is a mystery that the script gives mixed answers for, but they need to be sorted out in the playing.

Not surprisingly, Nava seizes upon a chance to renovate the house when a handyman is called in to address the ignored commode. The battle lines are drawn when Yoel, childishly, first refuses to budge, then gives an inch, the refuses to budge, etc. He hides his retentiveness in a transparent reverence for his father – portrayed as a great builder of early Tel Aviv (a portrait that is later undercut).

Without a viable answer to why these two are still connected, this vacuum at the center allows the secondary character of the contractor, Yigal Kadosh (Andrew Ross Wynn, a standout in A Noise Within's As You Like It last year) stands out as such an important figure. Of course, Hasfari has given him what seems undo dimension here, given some of the things he's glossed over. The pivotal character of Yoel's mysterious older brother, for instance, is much too sketchy, given that his actions are ultimately at the core of the drama. Was he married to Nava? How did Yoel's obsession with Nava from the age of 9 circumnavigate his older brotherís position? Kadosh arrives on the scene as if to provide comic relief, but ends up with as much definition as the central characters, thanks in part to a network of subplots that feature him and his son, Roíi, also well played by Brett Ryback. This story that has time for side excursions into Yoelís younger brotherís exploits (immaterial to the Yoel-Nava relationship) and the nursing home realities of Yoelís parents (hardly essential to establishing anything).

The parents have their own tangent about finding buried treasure. It's not as crazy as it seems when it, like so many of the messages woven into Hasfari's script, provides another metaphor: While there is gold in our pasts, we must be willing to break down our pasts in order to find it.

top of page

THE MASTER OF THE HOUSE

by SHMUEL HASFARI

directed by RICHARD STEIN

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

March 27-April 29

(Opened, reviewed 3/31)

CAST Joseph Cardinale, Stacie Chaiken, Jonathan Goldstein, Barry Alan Levine, Tyler Logan, Brett Ryback, Elizabeth Tobias, Bryna Weiss, Andrew Ross Wynn

PRODUCTION Narelle Sissons, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Tom Ruzika, lights; David Edwards, sound; Rebecca M. Green, stage management

HISTORY American Premiere

Jonathon Goldstein and Stacie Chaiken

Ed Krieger

Wasn't born to follow

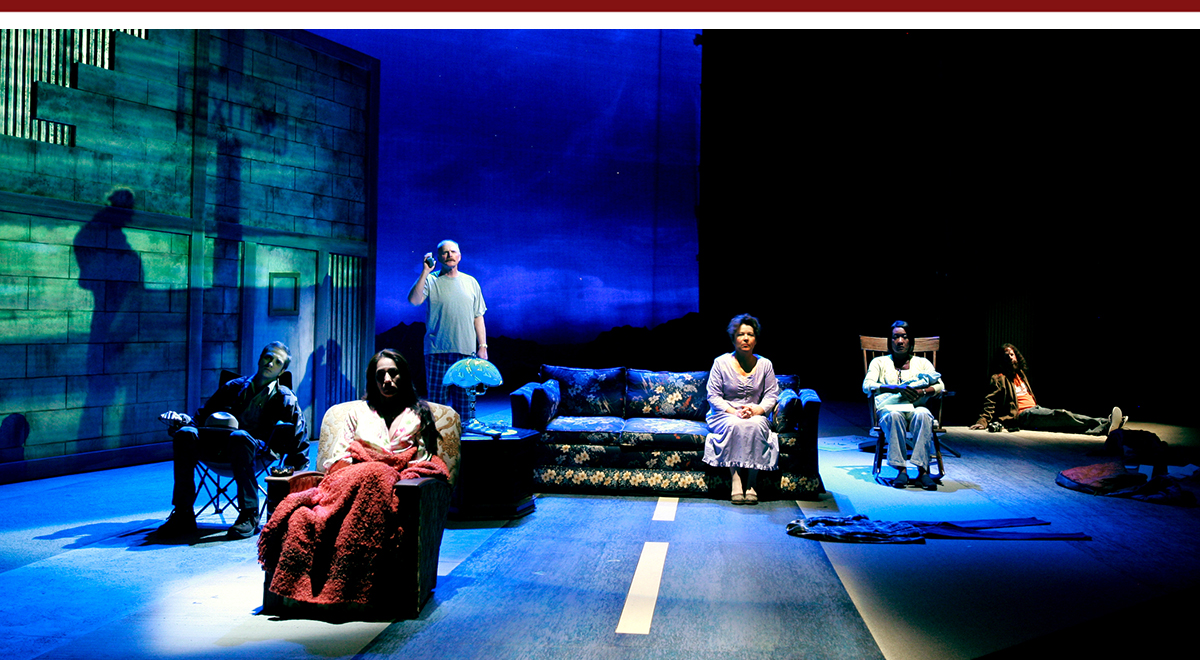

My Wandering Boy by Julie Marie Myatt, in its world premiere at the commissioning South Coast Repertory, is intriguing, daring and ultimately satisfying both in its storytelling and its story. While the text leans toward tracking a particular wanderer, the production opens up – literally, for a series of film clips by Austin Switser – to offer a gentle, non-judgmental view of the bedraggled army we once romanticized as tramps and hoboes but now see simply as homeless.

Bill Rauch directs the launch of this play by his Cornerstone Theater Company colleague. He syncs a fine cast led by Charlie Robinson to Myatt's spare, funny dialogue in a way that lets the characters be both natural and instruments of the writer's poetics. The corrugated upstage panels of Christopher Acebo's set open scene by scene like the aperture of a camera lens to reveal more and more sky. As pieces of living room furniture accumulate the portal widens; the more objects weigh down a wanderer's home, the greater the lure of the open road.

Thirty-year-old Emmett Boudin has disappeared. It's not clear whether he was pulled by freedom or pushed by responsibility. Emmett had the facile charms that win easy accommodation from others. His father says he was lazy. Either way, Emmett grew into a man-boy blissfully free of the need to justify his actions to parent or peer. After his parents (Richard Doyle and Elizabeth Ruscio) learned that Emmett's late grandmother left her estate to him, they hired Detective Howard (Robinson) to find him. Howard's sleuthing forms the motion of the play, leading him to three of Emmett's circle – a best friend (John Cabrera), a girlfriend (Purva Bedi), and a later girlfriend (Veralyn Jones) with whom he has a baby son.

That son, who becomes the only person Emmett favors with any rationale, reveals Emmett's humanity. And, while it would be hardly adequate in the real world, here the letter-writing seems to suffice. However, the stationary letter-reading – while logical – is perhaps too static.

Robinson has enough of the tough gumshoe to make the mystery engaging and sufficient twinkle to appear at risk of being seduced by the open road himself. Adding a performance that would be reason enough to see this production is Ms. Ruscio as the addled but emotional mother. She never falls off the center divider between character and comedy. Doyle delivers another nice comic turn, though it's hard to imagine anyone making sense of his character's shift from wistful nostalgia to irate dad in a single scene change. As the friend and lovers, Cabrera, Jones and Bedi assemble fully functioning, engaging people from the kits Ms. Myatt has provided.

Dramaturgically, there is blurring that Ms. Myatt intends but may not want to be as confusing as it is. The enigmatic character named John (Brent Hinkley), who kicks off the show by stepping into boots he may or may not have found by the side of the road, looks like a mad prophet of the highway. He'll surely be likened to every kind of pedestrian prophet from Jesus to Forrest Gump (whose cross-country jogger the hairy Mr. Hinkley resembles). John may represent the spirit of the drifter or he may in fact be Emmett. A backpack with contents belonging to Emmett ties these two together, especially the aforementioned video camera that another character references as belonging to Emmett and that John is seen holding. There is also Emmett's journal of musings with which John seems a little too familiar.

That John actually is Emmett seems unlikely, for it would mean that Howard is a terrible detective. That John killed Emmett for his belongings seems unlikely, too, as it would be completely out of tone with this dreamy play. It's more likely that Emmett has fallen through the cracks and landed in the flattened cardboard world beneath the urban overpass and that John has stumbled upon the cache left as a final sign of Emmett's exit. Meanwhile, as those two personalities merge and separate, the boots become the embodiment of the spirit of the wanderer and give the detective insight after he appropriates them for himself.

Myatt understands and accepts the wanderer gene, that historically male phenomenon whose dark side leads to abandoned jobs, families and selves and whose bright side leads to compulsive exploration of everything from the universe to the other side of the hill. The old soul in Myatt portrays her fellows as traveling at greater risk to themselves than to others. They are tuned to the siren's song from birth, struggling to balance the tugs of hearth and highway. Emmett's dad shut it out. John and Emmett gave in. Detective Howard, in Robinson's beautifully understated performance, manages to stay strapped to the mast with his eyes and ears open. As he listens, what we hear is the still-young but already wise voice of Ms. Myatt echoing great writers like Bob Dylan, in whose words the scratching at the straps can still be heard:

My toes too numb to step

Wait only for my boot heels to be wanderin’

I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade

Into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way

I promise to go under it

top of page

MY WANDERING BOY

by JULIE MARIE MYATT

directed by BILL RAUCH

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

March – May 6, 2007

(opened 4/6; reviewed 4/7)

CAST Purva Bedi, John Cabrera, Richard Doyle, Brent Hinkley, Veralyn Jones, Charlie Robinson, Elizabeth Ruscio

PRODUCTION Christopher Acebo, set; Shigeru Yaji, costumes; Lonnie Rafael Alcaraz, lights; Paul James Prendergast, sound; Austin Switser, video; Dara Weinberg, asst. director; Megan Monaghan, dramaturg; Randall K. Lum/Chrissy Church, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

John Cabrera, Purva Bedi, Richard Doyle, Elizabeth Ruscio, Veralyn Jones, and Brent Hinkley

Henry DiRocco

Power launch

With echoes of several masterworks, especially the Billy Wilder film with the similarly metered title, Sunset Boulevard, David Wiener's new System Wonderland takes us into rich, if charted, waters. But whether it's Wiener's dramaturgy, a central performance, or both, the journey ends with the feeling that there has been some drifting along the way.

The three-member cast in South Coast Repertory's world premiere, directed by David Emmes from a script commissioned by the theater, must triangulate a story that wants to explore several conflicting issues: pursuit of artistic integrity in a Hollywood system that eschews it; creative collaboration and mentoring between characters out to exploit those relationships; and, perhaps most importantly, a love affair whose protection is paramount despite little evidence of it.

The biggest challenge in all of this falls to Robert Desiderio, who as Oscar-winner Jerry Wolfe appears to be Max to the neo-Norma Desmond of Shannon Cochran's Evelyn Kinkade. But Jerry soon throws off any yoke of subservience. In fact, after many dry years, he is himself in need of getting back in the good graces of the studio. After submitting a new treatment to a production exec, he is sent a young film school grad to help him with his typing. Aaron, played John Sloan, back after his debut in SCR's wonderful production of The Retreat from Moscow, has the backstory of Jay Gatsby and the moves of John Guare's Paul in Six Degrees.

Wiener has given this three-sided story strong legs: reasons that they stay connected yet are propelled in pursuit of their own interests. Emmes serves him well with pacing and spacing that allow the story to breath as it powers forward. He also has an appreciation for what makes both the art and business of filmmaking endlessly fascinating. Still, as Jerry appears more and more to be the key to the balance he also feels increasingly one-dimensional. Consequently, Wiener's story begins to sink.

Whether it's murkiness in Wiener's script or a lead actor out of his depth, the character is not navigating these conflicting demands. And, when the play ends with sacrifice as the only explanation for what has gone down, we must send our memory back down the play's plotlines to determine whether Jerry was being loving or controlling.

In one exchange Jerry is haranguing Aaron about how to read the script. Two or three times he stops him, each time admonishing him: "No, read the words." Eventually Aaron satisfies him, but it's doubtful anyone in the theater, including Aaron, knows what he was after. It's an investment Wiener has made to show this man's conflicting sides. But he doesn't get the pay-off. All we heard is brow-beating.

We believe his wife loves him, even before she says so. But on three different occasions, when she shares a memory in hopes of eliciting affection, Jerry does not recall them. In an opening scene that shows him worried about his appearance for an imminent meeting, he immediately begins bullying the guest without any interest in him. And finally, though his ego, reputation and perhaps marriage hinge on getting a script accepted, he sends an inexperienced and potentially untrustworthy proxy off to do his bidding. All of these conflicting aspects can be sorted out from hints in the script. But it takes some doing because they're not evident in the playing.

Ultimately, however, the historical marker that buoys this South Coast Repertory premiere may be the debut not of the writer but of Cochran. A popular actress in Chicago and winner of an Obie for the sensational Bug a few years back, her only noted Southern California credit is Tina Landau's Space, at the Taper in 1999. As she displayed in the reading of Wonderland at this theater's 2006 Playwrights Festival, her performance is always in touch with her character's core. As if keeping her foot on her third rail, she stays connected to that submerged source. Not only are her actions always understandable, she gives Evelyn the full dimension: tragic, hopeful, playful and dangerous. Wiener, Emmes and Desiderio need to see if Jerry really deserves to live with her.

top of page

SYSTEM WONDERLAND

by DAVID WIENER

directed by DAVID EMMES

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

April 20-May 13, 2007

(rev. 4/29)

CAST Shannon Cochran, Robert Desiderio, John Sloan

PRODUCTION Myung Hee Cho, sets/costumes; Lap-Chi Chu, lights; Tom Cavnar, sound; Victor Mouledoux/Chip Tompkins, video; Martin Noyes, fights; Erin Nelson, stage management

HISTORY Commissioned by SCR World Premiere

Robert Desiderio, John Sloan and Shannon Cochran

Henry DiRocco

Site lines

In The Women of Lockerbie, through May 12 at the Actors' Gang in Culver City, art and accuracy have settled their differences to bring an extraordinary story to the stage. Deborah Brevoort's one-act, real-time drama imagines that important night seven years after the 1988 downing of PanAm Flight 103 when a simple act of decency took on epic proportions. With nods to Greek Tragedy, Shakespearean rants on Scottish heaths and American dramas about the power of the common people, Brevoort has created a powerful reminder that air disaster victims include more than the people who fall from the sky. There are also the people who miss them. And, the people who find them.

In December 1988, the terrorist bombing aboard a New York-bound PanAm flight out of London turned a Boeing 747 into a meteor shower over Lockerbie, Scotland. Everyone on board and 11 more on the ground were killed. Most of the 270 victims were American and the majority of those were residents of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The tragedy faded first from the headlines, then from memory. Even the airline went out of business and disappeared.

In 1999, interest was renewed when two indictments were handed down against Libyan men charged with the bombing. The interest continued through the subsequent trial that ended with the sentencing of one defendant in 2002. During that time, Brevoort's play, which she had spent five years writing, was introduced with the support of a 2001 Fund for New American Plays grant.

The Women of Lockerbie now gives that historical event a timeless source of revival. It is being produced around the country, but indications this is the West Coast premiere. Director Brent Hinkley (whose acting is currently on display in SCRís My Wandering Boy) infuses the Actors' Gang staging with a visceral quality.

The play is set in the open space that was the debris field from the wreckage. In the middle of a December night, the sky and earth merge in the inky darkness. Flashlight beams and distant voices break the stillness at rise. A man calls out for his wife. She calls back. But it is her son Adam, a passenger on Flight 103 returning from study abroad, whose name she cries. A dozen passengers seated closest to the explosion disappeared without a trace. Adam was one of these. Without a physical symbol – even a bone fragment or jacket button – for closure, Madeline's extraordinary grief has continued unabated.

Though the entire cast serves Hinkley well, the center of the production is Kate A. Mulligan, who plays Adam's mother Madeline. Her wails and contortions are of Greek proportion, a Munch scream come to life. Mulligan makes a brave choice in pulling out the stops for this characterization and it will unnerve some. However, she somehow shapes the hysteria and keeps a real person in sight.

Sibyl Wickersheimer's entire set is a steeply raked hillside of pitch-black plywood. Bosco Flanagan's spare lighting and John Zalewski's beautifully eerie sound design help turn this play set in Scotland into a modern Scottish Play. Madeline's dazed wandering of the site bears more than passing resemblance to Lady Macbeth's sleepwalking. The arrival of three women (Mary Eileen OíDonnell, Terri Lynn Harris, Anna Sommer), who occasionally move in coven choreography, underscores the sense that these kindly community women have one foot in a mystical otherworld. The women, some with immediate family killed by the falling jet, are no strangers to grief. Patti Tippo plays a fourth Lockerbie local.

Brevoort has brought Madeline and Bill Livingston (Silas Weir Mitchell) back to Lockerbie on the anniversary of the crash. This action by the fictional Livingstons coincides with an historical event. Hundreds of local women, incensed that the U.S. government still had not released the personal belongings of the dead – including the bloody clothes they were wearing – have chosen this seventh anniversary to raise their voices in protest.

As backdrop to Madeline's hopeless quest, the women confront the U.S. official (Robert Shampain) in charge of the warehouse. In a case of real-life improvisation, the women come up with a gesture that will serve the victims, the survivors and the officials. Their real-life demand, which certainly serves the drama as well, is that they be allowed to perform a service - a humane act of cleansing, and closure.

The Actors' Gang has given Brevoort's play a fitting entry into Los Angeles. It's no surprise that the production has been extended to May 12.

top of page

THE WOMEN OF LOCKERBIE

by DEBORAH BREVOORT

directed by BRENT HINKLEY

ACTORS' GANG

through May 12, 2007

(reviewed 4/6)

CAST Kate A. Mulligan, Silas Weir Mitchell, Mary Eileen OíDonnell, Terri Lynn Harris, Anna Sommer, Patti Tippo, Robert Shampain

PRODUCTION Sibyl Wickersheimer, set; Ann Closs-Farley, costumes; Bosco Flanagan, lights; John Zalewski, sound; Amber Koehler, stage management