AUGUST 2012

Click title to jump to review

AS YOU LIKE IT by William Shakespeare | The Old Globe

THE BLUE IRIS by Athol Fugard | Fountain Theatre

MONTANA TALES by Troy Evans | Audubon Center

Back to Arden

As You Like It is Shakespeare’s tribute to the clarity that nature can provide for restriction-weary city dwellers. More than 300 years before the American utopian movement and the 1960s "back to the garden" stampede, Shakespeare has children shed their commanding elders – whether fathers, governors, or both – for the freedom of the Forest of Arden. The message remains timeless, and in Adrian Nobel's staging for the festival at The Old Globe, it is a summer tonic that's easy to swallow.

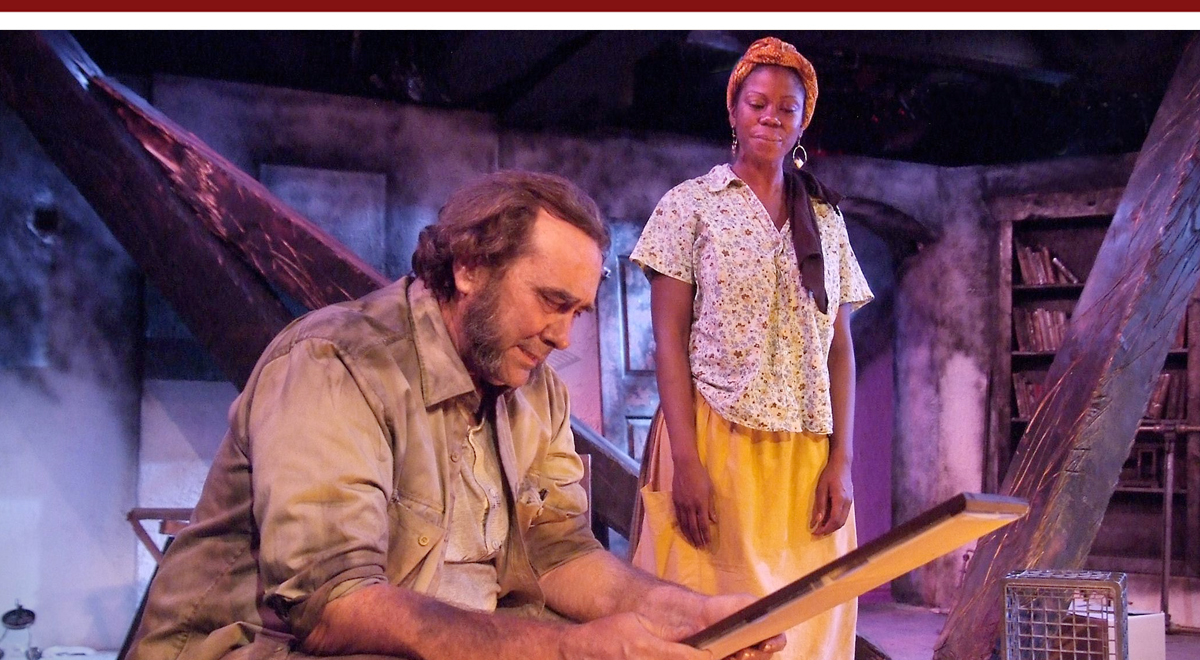

In the opening scenes, the youth – in the form of Rosalind (Dana Green), her cousin Celia (Vivia Font), and a strapping newcomer named Orlando (Dan Amboyer) – are in a losing battle with the establishment. Rosalind’s father, Duke Senior (Bob Pescovitz) has been banished to the forest by his brother, Duke Frederick (Happy Anderson). Frederick, concerned about his niece Rosalind's influence over his daughter Celia, sends her packing for the forest, too. But the devoted Celia pledges to go with her. Along with Touchstone (Joseph Marcell), they head out to make a new life. Meanwhile, Orlando, after a victorious wrestling match with court-favorite Charles (Matthew Bellows), hoists his ancient attendant, Adam (Charles Janasz), over his shoulder and lumbers out into the woods.

Once outside the city limits, the wanderers crisscross, intersect and meet various country folk. For protection, Rosalind dons male garb and the name Ganymede, while Celia plays her sister, Aliena. So successful is her disguise that, when they eventually happen on Orlando, he is unaware that it is Rosalind under Ganymede's garments. In the days since leaving the city, Orlando has become so deeply in love that he has begun tacking anonymous paeans of love to Rosalind on trees.

Among Duke Senior's band of forest dwellers is Jacques, third brother to Oliver and Orlando. It is Jacques who recites Shakespeare's famous Seven Ages of Man Speech, and ?? gets off to a great start as he is allowed to give the opening lines without intrusion by the director. Unfortunately he is soon made to get up and move around, Noble apparently concerned his audience needs some action to keep their attention, and he is engaging with hail fellow jocularity some of the merry-ready band. It’s unfortunate because it had started as one of the most natural moments in the play, by one of the real actors in the cast, and was frittered away.

Green has quickly risen from our first viewing in Cousin Bette, to the show at Shakespeare Santa Cruz, to second banana in Midsummer lead roles at South Coast Repertory’s Pride and Prejudice. Except for Cousin Bette, these have all been fairly lightehearded exhibitions and she has that in her DNA. She is however, capable of great range, as is Font, who after getting high marks for her ?? in Inherit the Wind, is an ebullient Celia.

It is an extremely watchable and clear version, if not particularly exciting. The stagecraft that helped make Noble’s Tempest last year so thrilling is missing here, other than a well-staged wrestling match. Going into the forest the set relies on the real trees beyond the upstage wall, but they are not lit enough to bring the sense of the forest to bear and except for some snow falling, the scenic design is Spartan.

To establish the sense of overbearing establishment, the city gets an air of Nazi Germany or Poland with a full size box car being loaded with citizens, dressed in ‘30s clothing, being forced onto the . It is apparently part of the Duke’s forcing out of his opposition, but it’s hard not to see it as an extermination. A lot of trouble to go to, with a high risk of that assumption, which is heavy-handed and disproportionate for this story.

top of page

AS YOU LIKE IT

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by ADRIAN NOBLE

THE OLD GLOBE

June 10-September 30, 2012

Opened 6/29, rev’d 8/14

CAST Dan Amboyer, Happy Anderson, Matthew Bellows, Adam Daveline, Jeremy Fisher, Vivia Font, Dana Green, Charles Janasz, Jesse Jensen, Joseph Marcell, Danielle O’Farrell, Allison Spratt Pearce, Bob Pescovitz, Christopher Salazar, Jacques C. Smith, Adrian Sparks, Jonathan Spivey, Jay Whittaker and Sean-Michael Wilkinson; with Rachael Jenison, Deborah Radloff, Stephanie Roetzel, Whitney Wakimoto and Bree Welch

PRODUCTION Ralph Funicello, set; Deirdre Clancy, costumes; Alan Burrett, lights; Lindsay Jones, sound; Shaun Davey, music; Steve Rankin, fights; Elan McMahan, music direction; Christine Adaire, vocal/dialect; Bret Torbeck, stage management

Dan Amboyer, Matthew Bellows, center, with full cast

Photo | Henry DiRocco

Survivor guilt

South Africa's Athol Fugard, a major influence on American theater in the 1970s and '80s, has again chosen Los Angeles' Fountain Theatre for the U.S. premiere of his latest play. In 2010, The Train Driver followed a man haunted by his innocent complicity in a stranger's suicide. In The Blue Iris (through September 16), two characters share guilt over a death they might have prevented.

Through a story about moving on after crushing loss, Fugard examines troubled marriages, childish infatuations, and an artist's drive to go beyond documentation to revelation. A couple more, clear in the script but not in the playing, echo novelist-poet Thomas Hardy's life and Fugard's own. These are sketched with minimal detail during the 75-minute one-act, and, as a result are not fully realized. But the poetics and human understanding that drive the story reveal Fugard's still-engaging literary powers.

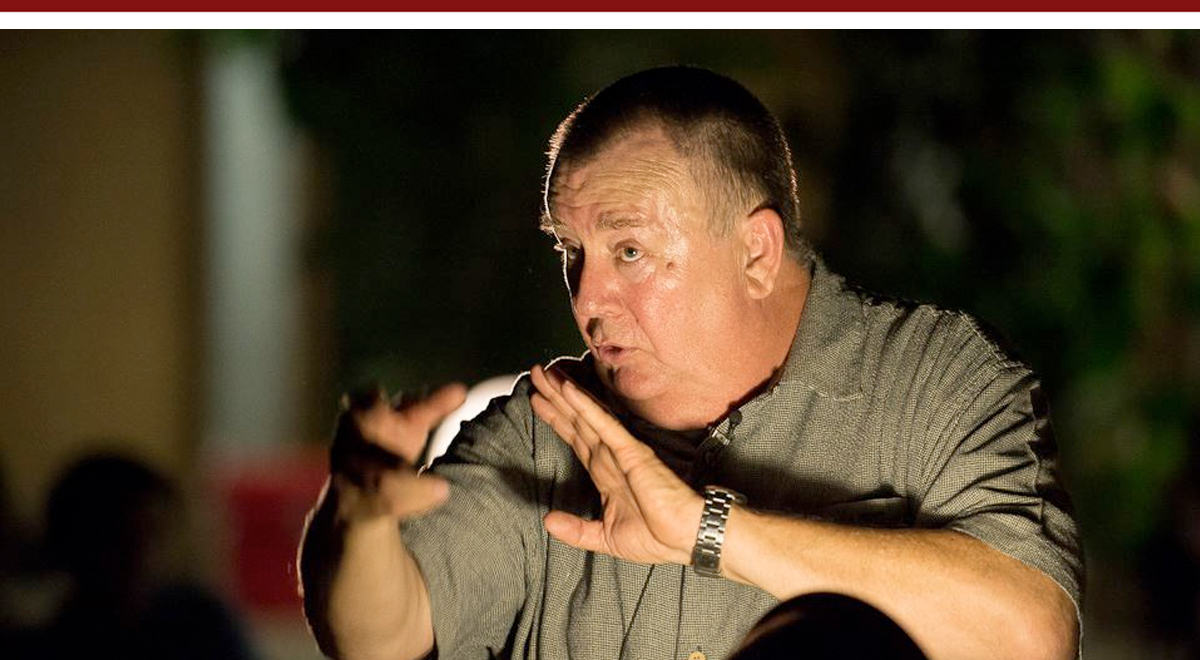

Fountain's Co-Artistic Director Stephen Sachs is again director, and leading the cast is Morlan Higgins, who also played The Train Driver's title role. Here Higgins is Robert, a Karoo farmer whose wife recently suffered a fatal heart attack after a storm cause their home to burn. The cast also includes Julanne Chidi Hill as Rieta, their younger woman housekeeper, and Jacqueline Schultz as Robert's wife Sally, who appears through Robert's memory in a single, explosive scene.

This confusion over just what happened and when is exasperated by the mix of detail and vagueness. For instance, it's not clear how long before the play began, the fire occurred that lead to Sally's heart attack:

Robert: How long is it now since the fire?

Rieta: I stopped counting.

We assume it's been a week or two, but is that long enough to "stop counting?"

There may also be a disconnect between the character Fugard wrote for Robert (whom the script describes as in his late Seventies) and the actors playing him here, and in the world premiere at the National Arts Festival in South Africa last July. Both Higgins and Graham Weir appear to be in their 50s. (Weir does wear a gray beard reminiscent of a younger Fugard.) Although the playwright is clearly comfortable with the change, if he wrote the part thinking Robert, like himself, a character late in life rather than midlife, the decisions and reactions he has after losing his wife are grounded in different realities.

That has effects on the kind of relationship Robert and Rieta might have. Here, she appears to carry a torch for the hardened widower, something logical for a man 15 or 20 years older that would be unlikely for a many 40 years older.

What is clear, is Fugard's knack for combining the gritty and the beautiful. Life's dichotomies are symbolized in the storm that brings both fire and rain. There are reasons for and against moving on, and they drive Robert and Rieta discussions about burying the guilt they feel, and leaving the house and its pain behind. Helping bring Robert to his final acceptance, will be a final vision of his wife, who returns in a nightgown to reveal her feelings a drawing of a blue iris. It was the first sketch that launched her decades-long documentation of Karoo plantlife.

As central metaphor, the tiny bloutulp, or "blue iris," is a fertile image. After the 1967-1973 drought decimated vegetation across South Africa's Karoo region, the blue iris was the first plant to return around the home. It symbolizes the resilience of the people of this region, and its strength and beauty is what appealed to Sally's artistic eye. What would frustrate, her, however, is the plant's hidden secret–enough poison to kill an ox and become the bane of local farmers.

On Jeff McLaughlin's burned-out living room set, which he also lit, Robert and Rieta sort through household belongs among the fire's wreckage. Sally had been alone in the house while Robert and Rieta had chosen to ignore her terrified request for their presence as the storm approached. Exactly what happened to kill Sally is as foggy as when it happened.

It is also confusing, evening with allowance for irrationality, that Robert would describe his actions on another day, which do not seem consistent within their own recounting.

Hardy, whose poem "The Voice" prefaces the script, lost his wife Emma suddenly. Like Robert and Sally, theirs was a complicated, often estranged relationship. But after her death he was obsessed with her, writing within the month after the loss, "Can it be you that I hear? Let me view you, then, / Standing as when I drew near to the town / Where you would wait for me: yes, as I knew you then, Even to the original air-blue gown!" He did not publish it, however, until two years later, after marrying his secretary, who was 39 years his junior.

While, if memory serves, the gown in the production is pink, the script specifies "She is wearing the pale blue nightgown she wore on the night of the fire."

If Rieta, as she says, "was 8 years old," at the beginning of the drought, she would be It would be odd to think that the parallels are accidental, especially with The Voice quoted in the script's overleaf. For some, the obfuscation in how it fits together may detract from the play's beauty, the soot that inevitably clouds the sketch. He has some guilt about bringing Sally to this spot, just as it was turning from a place where a "magical carpet of flowers … rolls out in Spring

Many obviously have, and most importantly, as he celebrates his 80th birthday in 2012, one hopes Fugard has. But, there will be those in the audience, like South African critic Peter Tromp, who wrote in his review of the world premiere, "I certainly saw glimpses of what the audience got onto their feet to applaud at the end, but I couldn’t for the life of me shake what a deeply flawed staging of a flawed, if heartfelt play ‘The Blue Iris’ is."

top of page

THE BLUE IRIS

by ATHOL FUGARD

directed by STEPHEN SACHS

FOUNTAIN THEATRE

April 11-May 13, 2012

Opened 8/24, rev’d 8/25

CAST Morlan Higgins, Julanne Chidi Hill, Jacqueline Schultz

PRODUCTION Jeff McLaughlin, set/lights; Naila Aladdin Sanders, costumes; Peter Bayne, music/sound; Terri Roberts, stage management

HISTORY Premiered in June 2012 at the National Arts Festival of South Africa. U.S. Premiere. Produced by Deborah Lawlor and Simon Levy.

Morlan Higgins and Julanne Chidi Hill

Photo | Ed Krieger

Flakes from the snow globe

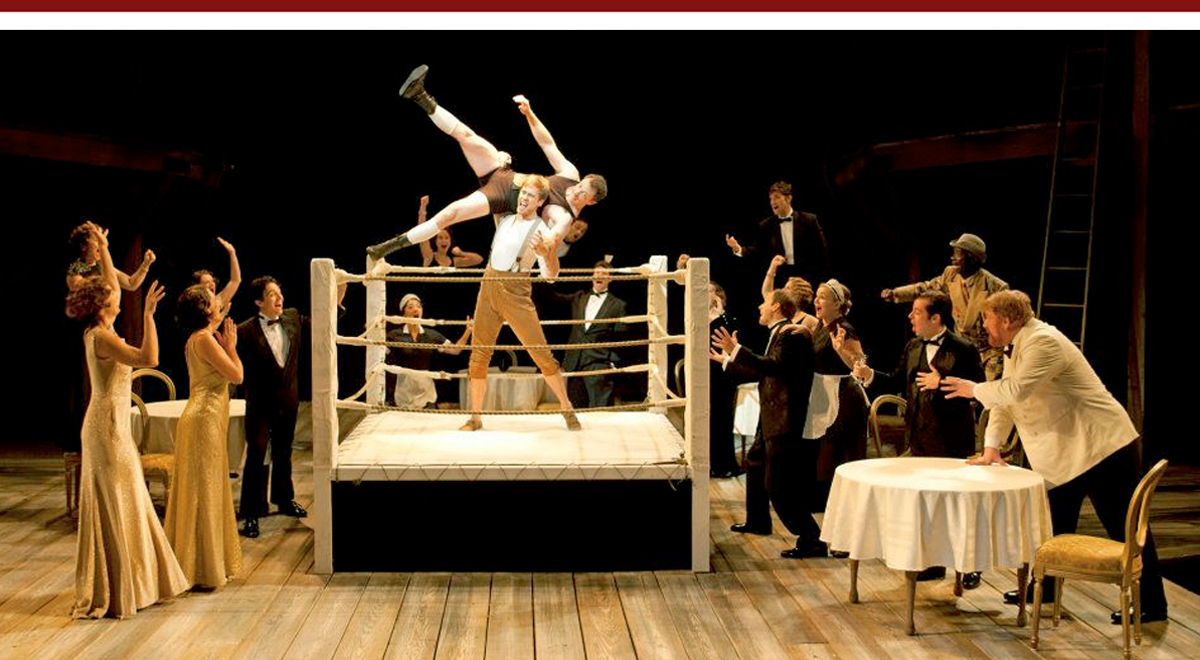

Actor Troy Evans began his August 11 performance of Montana Tales and Other Bad Ass Business with a brief show and tell, sharing some items from his eclectic home collection: razor-blade sharpeners, a disposable stapler with a "lifetime guaranty," and a prop to put the wind at the back of any campfire storyteller – a can of Joan of Arc-brand pork and beans.

Then, as a hot day's sun reluctantly fell behind Mt. Washington, he held up a thin volume on 19th Century vigilantism in his home state of Montana. He told the 250 people seated on the courtyard of Montecito Heights's Audubon Center that years ago his wife Heather McLarty, knowing he would enjoy its profiles of lawmen, lawbreakers, and some like Henry Plummer who were both, left the book by his reading chair as a surprise. He related some of book's highlights, such as Plummer's trick of faking tuberculosis to get out of jail. In the process we moved beyond the artifacts of his home collection and into the traveling gallery of his recollection. Here live the larger-than-life characters from Western history and his own experiences that he shared during nearly two hours of vivid storytelling.

The performance was a benefit for the Southwest Museum of Indian Culture, visible in the fading light across the arroyo, and in danger of going dark after a shadowy merger with the Autry Museum in 2003. In prefatory remarks, Evans and L.A. City Councilman Ed P. Reyes, who introduced him, briefly explained the museum's precarious situation.

Evans is an accomplished actor recognizable from dozens of prominent roles in such films as Phenomenon and the television shows "China Beach" and "ER." Because of that, he is able to create, along with the character portraits and setting, the emotional context of each story. Whether it's the mining fields of Montana or the minefields Vietnam, we feel how it felt to be present when the incident he recalls occurred.

For instance, we are relieved when dust-trails from dozens of pick-ups appear out of the four corners of endless Montana prairie, arriving just in time for the mountaintop performance of Merchant of Venice in which Evans will perform Shylock – only his second stage role. We anxiously patrol with his unit near the Viet Cong lines, and understand how the decision was made that has haunted ever since.

During several stories from Evans' wild years following his return from Vietnam and prior to his acting career, we watch his explosive reaction to an insensitive customer while tending the bar he owned. Following his conviction for assault, we join him in the mental institution where he served part of his sentence in rehab. There, in an emotional roller-coaster that is a highlight of the evening, he organizes a patient talent show that, with echoes of Kesey's Cuckoo's Nest, becomes a bittersweet showcase of human survival.

Among the performers are Henry Woodbury, with glasses so thick his eyes appear as big as "goldfish swimming in Mazola oil," and Harper Wade, whose self-perception is of someone who worked in Gone With The Wind and the Eisenhower and Johnson Administrations. Evans, of course, without any fuss, becomes each character. As Wade, he repeats the opening lines of his talent show song, before abruptly ending his performance and heading off stage. When he reaches the Stars and Stripes, in its stand at the side of the stage, he salutes, and, in an exquisite voice from somewhere in his past, sings a patriotic anthem that carries the emotional truths that are reason for the sacrifice of his reason. In Evans' transporting account, this evanescent moment, and the man who lived it, are restored.

Perhaps it's the outdoor setting, the overarching oaks, or the cause of preserving a museum dedicated to Indian Culture, but Evans' performance feels a part of the great storytelling tradition of the West. However, unlike the Tall Tales of Mark Twain, Bret Harte, or Charlie Russell, which were either concocted out of thin air or exaggerated beyond possibility, Evans' narratives are fastidiously factual. Stretching them would only weaken their impact. That the hero of one Vietnam story was in the audience, and asked to stand at the end of that story, made that tale more inspiring and instructional than any ancient myth.

The evening's only truth-stretching, in fact, may have been when Evans allowed as how, of late, his mind had taken on the nature of a snow globe constantly astir. He said early on that he hoped he would be able to grab on to and recall enough of the stories that now swirled around inside his head like the fluttering flakes inside the globe.

Not only were his recollections sharp, they were loosely bound by, not an imposed theme or context, but by a reassuring sense of connectedness. That first story from the book on vigilantism, in fact, had ended with Evans' surprise discovery that the random gift, unbeknownst to his wife, had belonged to an ancestor: a provenance of providence. And it had given the evening a respect for the mysterious connections that lie all around, beyond our awareness, beyond our histories, out in the province of our stories.

top of page

MONTANA TALES AND OTHER BAD ASS BUSINESS

developed and performed by TROY EVANS

AUDUBON CENTER

August 11, 2012

PRODUCTION A performance to benefit the Southwest Museum of Indian Culture, hosted by the Friends of the Southwest Museum