FEBRUARY 2007

Click title to jump to review

A PICASSO by Jeffrey Hatcher | Geffen Playhouse

DEFIANCE by John Patrick Shanley | Pasadena Playhouse

THE FOUR OF US by Itamar Moses | The Old Globe

JAMAICA, FAREWELL by Deborah Ehrhardt | Whitefire Theater

THE MARVELOUS WONDERETTES by Roger Bean | El Portal Forum Theatre

THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS by Richard Nelson | Laguna Playhouse

SPEED-THE-PLOW by David Mamet | Geffen Playhouse

WHO'S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? by Edward Albee | Ahmanson Theatre

Marvelous

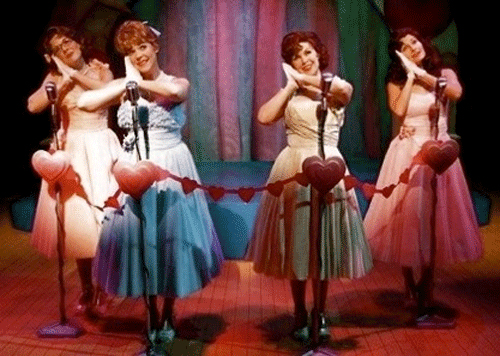

An evening with The Marvelous Wonderettes may look to be more trite time travel to the over-rhapsodized 1950s, but it breaks though its camp boundaries to free a score of radio hits from dashboard grills and Oldies bins for a touching, torchy, hilarious revue of show-stoppers. Roger Bean’s just-enough story and direction, Janet Miller’s imaginatively busy choreography, and the deft musical and comedic timing of Kirsten Chandler, Kim Huber, Julie Dixon Jackson and Bets Malone give "Girl Groups" of the ‘50s and ‘60s their own green acre of rock ‘n’ roll heaven.

Bean’s bio, which boasts his having "written 10 musicals," might lead one to believe this "New Pop Hit Musical Comedy" is an original. But the opening "bom-bom-bom" arpeggios of "Mr. Sandman" make it clear we’re safely in charted waters. While the script isn’t anything to write home about it, it serves the purpose of sketching the characters and stitching together the tunes. And, though it outlines the four friends along thick stereotypical lines - the boy-stealing babe, the gum-chewing bimbette, the four-eyed geek - these actors provide more than enough color to make them real. The producers and set designers have also provided little touches to help make the El Portal Theater (in North Hollywood, California) an environmental experience. These include marking a door in the lobby as the principal’s office, hanging championship banners in the gymnasium – mostly for chess and golf - and bits of non-threatening audience participation extend a good-natured atmosphere of the day.

Chandler, Huber, Jackson and Malone play high school seniors pressed into service as Prom entertainment when Springfield High’s go-to group, the all-male Crooning Crabcakes, are, well, delinquent. The device serves to excuse a concert format for these numbers, with the characters becoming increasingly individualized as the songs proceed. The line between the foursome's singing of popular hits and using specific songs to reveal something about themselves blurs as the evening wears on, especially in the second act. This, and the planting in the dialogue peripheral character names that will later pop up in lyrics, adds to the fun.

Thank goodness for bad Crabcakes. In forcing the distaff replacements to the fore, they create a rare showcase for four first-rank singers usually relegated to Broadway replacement casts, national tours and starring roles in the hinterlands. As a foursome the star-power sum is greater than the fame of its parts. Each performer is excellent, and every audience member will have a favorite. Favoritism, in fact, is encouraged: ballots for Prom Queen are collected midway in one of the bits of audience involvement. But the wind seems to be with Huber, who as the nebbishy Missy gets an arc from gawkiest to most fulfilled. She also is the only one to get a real object for her desires in one of the evening's highlights, "Secret Love"/"Mr. Lee."

In his introduction to The New York Times’ Great Songs of Broadway, the learned Alan Jay Lerner wrote that "an untrained musician can pick out a tune with one finger on a piano that may very well become a hit, but – and I repeat – but, it will never – and I repeat – never, endure. A genuine composer may pick out a melody with one finger on the piano and it can last forever." The marvel and the wonder of The Marvelous Wonderettes is that for two hours, a deck of four queens turn some 50-year-old radio hits into enduring musical theater.

top of page

THE MARVELOUS WONDERETTES

written and directed by ROGER BEAN

choreography by JANET MILLER

musical direction by ALLEN EVERMAN

orchestrations by

BRIAN BAKER

EL PORTAL FORUM THEATRE

September 29, 2007 through February 3, 2008

CAST Kirsten Chandler, Kim Huber, Julie Dixon Jackson, Bets Malone

PRODUCTION Kurt Boetcher, set; Sharell Martin, costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; Cricket S. Myers, sound; Jeff Weeks, wigs; Pat Loeb, stage manager

Kim Huber, Bets Malone, Julie Dixon Jackson and Kirsten Chandler

Michael Lamont

Back pages

Richard Dresser respects the power of good writing. He establishes that in the opening scenes of The Pursuit of Happiness, premiering through February 4 at the same Laguna Playhouse that commissioned it. The play begins with three soliloquies by lay writers: Annie (DeeDee Rescher) is writing a boastful year-end missive to her Christmas mailing list, her daughter Jody (Joanna Strapp) is editing her college application essay, and her husband Neil (Matthew Reidy) is practicing a speech he’s written for work. In the act of communicating their positions each reveals something about both his or her character and their author’s skill. Similarly, while Dresser infuses his work with the trappings of social relevance, he quickly reveals that, true to its billing, this play is also out for a good time.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. A show can sacrifice significance for comedy if the comedy works. And in Artistic Director Andrew Barnicle's excellent staging, it works well enough to redeem the director for last year’s excruciating And the Winner Is.

In this Pursuit of Happiness, the fuzziest of the inalienable rights offered in writing to declare independence in 1776, Dresser looks at one generation's launch and the older generation's assessment of their adulthood. But don't expect too much depth here. The vessel has definitely been streamlined for laughs. Anything too taxing was tossed out with the tea. Points about materialism, dead-end jobs, parents molding children as themselves, mid-life alienation, and kids who are wiser than their folks are here, but just to frame the fun. The final twist-tie that hurriedly bags the plot points is also just too convenient for words.

Still, larger themes of lost ideals can occasionally be glimpsed beneath the sketch-comedy like a playful leviathan shadowing a ship. We are reminded that when Annie and Neil were college age, children were suddenly adamantine in declaring independence from their parents. Forty years ago, post-war affluence had created the first youth market, drugs had hit the middle class, and televisions had carried images of it all into most living rooms. This fueled a sense of unity and entitlement that forged the youth secession of the late ‘60s. That may have been temporarily lost on Annie and Neil, but it will still resonate for many in the audience -- especially those who brought their own reference points with them.

Carrying the ball are Rescher and Strapp, who provide diametric balance to Dresser’s trans-generational turntable. Rescher is responsible for gaining most of the yardage and she keeps Annie amusing and winning. She gets superb support from Preston Maybank as a former college friend now in an important position – at least for the plot. Maybank brings pitch perfect honesty to this bad-hair cast-off from Annie’s past, earning his laughs and our empathy. One of Maybank’s best recent outings. Cummings registers well as Tucker, who serves as foil for both father and daughter. In Tucker, a co-worker of Neil’s who gets brought home on a daughter-recommended attempt to make a new friend, Dresser lowers the IQ to turn up the slapstick. Cummings, taking more license than the others, nails his lines with a dead-on-arrival delivery reminiscent of Steven Wright. In the Tucker-Jody scenes, Cummings and especially Stapp make the most of their chance to develop their characters as slightly more than reactive set-ups for Annie and Neil.

Tom Buderwitz has a sturdy set that fills the proscenium with the drama's principle residence. Pallets slide in and out stage left and right for additional scene locations. Julie Keen’s costumes are unobtrusive and she does have fun with sad-sack Tucker's choices. Lighting Designer Paulie Jenkins sets up a grid that lets everyone be nicely observed, and sound designer David Edwards provides his usual fine tuning.

From its Christmas letter opening to its "My Back Pages" curtain call, this is light entertainment that works, especially for the Boomers who remember when it was taken for granted that ideals would always be with us.

Ah, but we were so much older then.

top of page

THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS

by RICHARD DRESSER

directed by ANDREW BARNICLE

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

January 4-February 1, 2007

CAST Tim Cummings, Preston Maybank, Matthew Reidy, DeeDee Rescher and Joanna Strapp

PRODUCTION Tom Buderwitz, set; Julie Keen, costumes, Paulie Jenkins, lights; David Edwards, sound; Nancy Staiger, stage manager

HISTORY World Premiere, commissioned by The Laguna Playhouse

DeeDee Rescher, Matthew Reidy, Joanna Strapp, and Tim Cummings

Michael Lamont

Big deal

After two major Mamet productions – the crazy Romance at the Taper and the stilted Boston Marriage at the Geffen – proved less than powerful, and the planned premiere of his first musical, A Waitress in Yellowstone, fell off the Kirk Douglas calendar, L.A. was due for a reminder of why David Mamet is one of the great playwrights.

Here it is. On Wednesday, the Geffen Playhouse opened a letter-perfect staging of Speed-the-Plow, his 1988 comedy about Hollywood’s war between honor and whoring. Geffen Artistic Director Randall Arney directs a superb trio of faces familiar enough to attract the film folk who are the play’s ostensive subject, and the acting chops to reward Mamet-hungry theater fans.

Having seen Speed’s Broadway premiere and promoted its Southern California premiere at South Coast Repertory in 1990, I can report that Greg Germann, Alicia Silverstone and Jon Tenney are every inch as good as those casts. (Though it’s apples and oranges to compare the delightful Ms. Silverstone to Madonna, whose noisy stage debut was in the Broadway production, and worth reminding folks how special Joe Spano is on stage, as he was as SCR's Charlie Fox.)

Producer Bobby Gould (Mr. Tenney) is one day into his position as a studio executive with fresh power to “green light” scripts for production. At rise, he is still settling in: with boxes to unpack, painters' tarps to remove and posters of his unfamiliarpast projects to hang. His first visitor is an anxious Fox (Mr. Germann). No sooner has Fox eased himself through just enough crack in the door than Gould has picked up on a high-speed narrative about their industry. Without missing a beat, Fox joins in and, as if a needle had been dropped into the middle of their favorite record, the stage is suddenly filled the rhythm of their exchange.

Mr. Tenney and Mr. Germann give Gould and Fox the kind of fluid mutualism that makes these speeches worth savoring: all bluster, carefully shifting subtext, little content. It is a choreographed yin and yang, played out to Mr. Mamet's staccato syntax. The dance of the negotiators. They jockey for position, carefully respecting who is leading and who is following, and all the while working to pick the other's pocket of ideas, contacts and influence. We soon learn that a star-driven project has dropped into Fox’s lap, and he wants his Gould’s studio to produce it.

The third character is Karen, a temp in for Gould’s assistant, who is suspiciously absent on this important first (or second) day. Ms. Silverstone, the delightful surprise in Boston Marriage, may be the Geffen’s best ringer: a Hollywood name with a refreshing naturalness on stage and plenty of honest, spontaneous ideas in performance. She immediately establishes herself with the two stage veterans, maximizing the effects of the first words Mr. Mamet has given her. Meant to disrupt Gould and Fox's verbal volleying, the words silence their motor mouths like a boulder dropped on a gearbox.

The play’s structure showcases Karen in Act II, Fox in Act III, and gives a slight edge to Gould in an otherwise evenly split Act I. Yet, Mr. Tenney appropriately manages to own every scene he is in – and he is offstage for less than five minutes. His Gould is a schemer by nature of his intelligence and bon homie, not through cliched Hollywood smarminess. He’s the frat guy from college who, without artistic sensibilities or a real work ethic, had a knack for getting the breaks and taking full advantage of them. He now sits in a position of power and wealth, trying to produce movies that the highest number of people will pay to see.

In Hollywood, where only fools assume a deal is guaranteed to go through, there is an underlying suspense to the Gould-Fox story. But Mr. Mamet’s plot is not the point. His interests go beyond Hollywood, to questions of friendship in a competitive society, the leveling effects of love – if not sex – in business, and the elusiveness of purity.

Karen may be a schemer like the men or simply an innocent excited by the opportunity to do something meaningful. The men, for whom the meaningful has long been meaningless, are operating on lower evolutionary rungs – the single-cell culture of the Big Sell. Whether she is stooping to conquer, to make the world a better place, or simply to schtupp is open to debate. What is certain is that Mr. Tenney has given us a definitive Bobby Gould, Ms. Silverstone continues to establish herself as a worthy stage actress, Mr. Germann has a special gift for physical and vocal stage comedy, and Mr. Mamet again has the moral authority to go back and hit on that Waitress in Yellowstone

top of page

SPEED-THE-PLOW

by DAVID MAMET

directed by RRNDALL ARNEY

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

February 7-March 25, 2007

CAST Greg Germann, Alicia Silverstone, Jon Tenney

PRODUCTION Robert Blackman, set and costumes; Daniel Ionazzi, lights; Michelle Magaldi/Dana Victoria Anderson, stage management; Amy Levinson Millán, dramaturg (Previews 1/30, Opens 2/7, Closes 3/25. Reviewed: 2/8)

HISTORY West Coast Premiere

Jon Tenney and Alicia Silverstone

Michael Lamont

On the rocks

The first names in the mythology of American marriage are George and Martha. For the country’s first 180 years they stood for the Father of Our Country and our first First Lady and reminded us that great lives are even greater when supported in wholesome matrimony. In October 1962, with the Broadway premiere of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, another set of George and Marthas -- the Washingtons’ bi-polar opposites -- clawed their way to the top tier of marriage folklore and claimed their places as the first family of Marital Strife.

In November 2005, under the direction of Anthony Page, Bill Irwin and Kathleen Turner became Broadway’s latest George and Martha. A Ben Brantley benediction opened a box office flood that carried the cast to London in 2006 and then earlier this month into L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre. It arrives here amid much fanfare and trailing awards from those previous stops: a Tony Award for Mr. Irwin, a London Critics Circle Award for Ms. Turner and Brantley’s New York Times declaration that Ms. Turner, "a movie star whose previous theater work has been variable, finally secures her berth as a first-rate, depth-probing stage actress."

It is now 45 years since the play’s controversial debut, when it earned the Pulitzer Prize for Drama only to have the committee’s more powerful and less courageous members suspend the award that year because of the play’s language. Today, neither the language nor the vituperative husband and wife battles will ruffle audiences used to profanity-spewing, chair-throwing guests common to viewers of Jerry Springer, Dr. Phil and the like.

Still, Albee’s script leaves a sting. He had much more in mind than the shouting, and while we certainly leave the Ahmanson with an appreciation for insight he has buried beneath the belligerence, there’s a lingering sense that we are not seeing the definitive Martha. In Turner’s interpretation, she seems particularly saddled with the requirement that she be dominant in every scrap of dialogue. The obvious exception, her Act III-opening soliloquy, may be all Albee meant to allow her for significant nuance, but one wishes to somehow catch more of the complexity within this historic character. For whatever reason, the sameness of the dynamics in her exchanges, with volume being the primary modulator, grows tiresome over the three hours. Her two-character scenes with George, which one expects to sound routine after their years of marriage, feel like dead ends. For his part, Irwin fares better, able to create noticeable topography as he maneuvers his underdog George around his sniping wife. There is more a sense that he finds the sport in locking horns with the bullying Martha. There's a noticeable rise in his energy level when the Nick and Honey arrive, as if stoked by the fuel of two pieces of green firewood.

George is a history professor at an East Coast university where Martha’s father is president. Martha spends her days at home, nurturing resentments at having proved a non-starter, and swallowing her pride on shots from the rolling stock of liquor bottles. Albee knows that Martha’s biggest problem with men is not George but Daddy. If anybody stunted her it was he. Martha, however, does not know this and that is what makes these torturous hours intriguing. Rather than confront her own father, whom she is trapped in childlike adoration of, she goes after her accommodating husband.

When the play begins, George and Martha are stumbling into the comfortable living room (designed with loving detail by John Lee Beatty) after a dinner party for faculty at the home of Martha’s father. Following another long day of gnawing at each other and a night of heavy drinking, George is ready to retire. But, at her father’s request, Martha has invited another couple from the party to stop by. Kathleen Early is Honey and David Furr is Nick, new to the production for L.A. Despite a voice that sounds unnatural (which may be Page’s fault given the "overshrill" complaint from Brantley about an earlier actress), Early’s Honey feels appropriately clueless. We can see the beginnings of another serious stay-at-home alcoholic in her Honey.

Furr has a bigger challenge, having to make Nick – even after hours of drinking at the Martha’s father’s house – begin the play as an uptight and self-righteous man who will within hours reveal secrets about his relationship with Honey and then have sex with the arguably influential but hardly appealing Martha. It’s a tough row to hoe.

Martha’s castrating contempt for all men is the result of her unaddressed anger with her father. She berates George for being a failure compared to the old man, hoping he’ll take the bait and channel her loathing as proxy.

As the play’s title indicates, however, she is completely oblivious to these subconscious impulses. Martha spontaneously comes up with the parody of the Disney tune "Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?" during the dinner party at the home of her father – her Big Bad Wolf. Her frightened subconscious carefully changes the words to be about Virginia Woolf, which signals instead that Martha is educated while it invokes the aura of a brilliant, suicidal woman. It nevertheless remains the taunting of an immature schoolgirl.

Martha’s most telling act of passive-aggression towards her father, however, is that she has brought Nick and Honey home as a favor to her father, who wants them to feel more welcome in town. And then she proceeds to do everything she can to destroy them.

top of page

WHO'S AFRAID OF

VIRGINIA WOOLF?

by EDWARD ALBEE

directed by ANTHONY PAGE

AHMANSON THEATRE

February 6-March 18, 2007

CAST Kathleen Early, David Furr, Bill Irwin, Kathleen Turner

Irwin / Rosegg

PRODUCTION John Lee Beatty, set; Jane Greenwood, costumes; Peter Kaczorowski, lights; Mark Bennett/Michael Creason, sound; Rick Sordelet, fight direction; Susie Cordon, stage management