JANUARY 2009

Click title to jump to review

AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS book by Jules Verne, adapted by Mark Brown | Laguna Playhouse

PIPPIN by Roger O. Hirson and Stephen Schwartz | Mark Taper Forum

STORMY WEATHER by Sharleen Cooper Cohen | Pasadena Playhouse

WAITING FOR GODOT by Samuel Beckett | A Noise Within

Comedy and Dramamine

The well-traveled 1872 novel Around the World in 80 Days by Jules Verne, had already inspired films, plays and musicals when writer/actor Mark Brown returned the armchair adventure to the stage in 2001. His two-hour comedy for a cast of five properly condenses the sprawling yarn, lingering longest, as does the book, in India and America.

Verne set his second to the last – and most popular – novel contemporaneous to its publication. The American transcontinental railway was three-years old, and India’s patchwork of provincial lines seemed reliable enough to fill in the last gaps for a multi-mode circumnavigation of the globe. And so, within 80 Days, the early master of science fiction set out to celebrate real achievement in a whopping adventure yarn that also provided a travelogue of exotic peoples and places. Of little interest to Verne, and no interest to Brown, was exploring the inner terrain of the central character’s obsessive personality.

Of no interest to Verne, but great interest for Brown, was twisting the tale into a zany comedy. Brown, with director Michael Butler as over-enthusiastic accessory, creates a madcap air of commedia del arte silliness and shouting. It’s Jules Verne with ADD, performed by a rolling stock of characters who seem to want to punctuate their lines with bicycle horns.

Londoner Philius Fogg (Matthew Floyd Miller) is a taciturn man of mystery and obsessive behaviors. Like Will Ferrell’s character in Stranger Than Fiction, he is a clock-watcher who counts his steps from place to place. The story opens with him spending the evening, as is his custom, at his gentlemen’s club, where a lively debate ensues over how far a bank robber might have traveled since committing his crime earlier that day. A dedicated follower of timetables, Fogg suggests that the mastermind could be anywhere on the globe, now that circling it takes less than three months. When others scoff, he offers to prove it, and wagering half his savings and immediately begins his journey, taking with him the new manservant, Passepartout (Gendell Hernandez), he hired only hours before.

If natural and mechanical disasters weren’t challenging enough, Verne sets Detective Fix (Howard Swain) on his trail. Fix, who has gotten wind of Fogg’s hasty departure, assumes he is the bank robber. In India, Fogg and Passepartout save Adoura (Anna Bullard), a young widow about to be sacrificed in her husband’s funeral pyre, and adds her to his traveling party for her safety and added romantic possibilities. In America, more adventures occur including an American Indian attack, fended off with the help of Colonel Proctor (the best of Mark Farrell’s countless incarnations).

Fortunately, the incongruous clowning of act one, which infects all the actors save Buillard, is reined in during act two so the story can get serious enough for its London landing and resolution. The characters, all becoming more real as the roundtrip reaches its conclusion, sufficiently redeem themselves by curtain for, at this performance at least, a standing ovation.

While Butler’s hand may push the comedy past the comfort level, he and set designer Kelly Tighe get high marks for subtle playfulness in their design. Their wonderfully inventive reconfigurations of just a few set pieces create props, including an applause-generating elephant. The entire physical production, in fact, is inspired, with the exception of sound design by Jeff Mockus (predictably stately classical music for the opening scenes, some incongruous swing music for intermission, etc.), which seems particularly odd for a company usually able to rely on David Edwards’ noteworthy cues.

top of page

AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS

book by JULES VERNE

adapted by MARK BROWN

directed by MICHAEL BUTLER

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

January 6-February 8, 2009

(Opened 1/10, rev’d 1/24m)

CAST Anna Bullard, Mark Farrell, Gendell Hernandez, Matthew Floyd Miller, Howard Swain

PRODUCTION Kelly Tighe, set; Todd Roehrman, costumes; Kurt Landisman, lights; Jeff Mockus, sound; Lisa Anne Porter, dialect; Rebecca Michelle Green/Jennifer Ellen Butler, stage management.

HISTORY Co-produced with San Jose Repertory

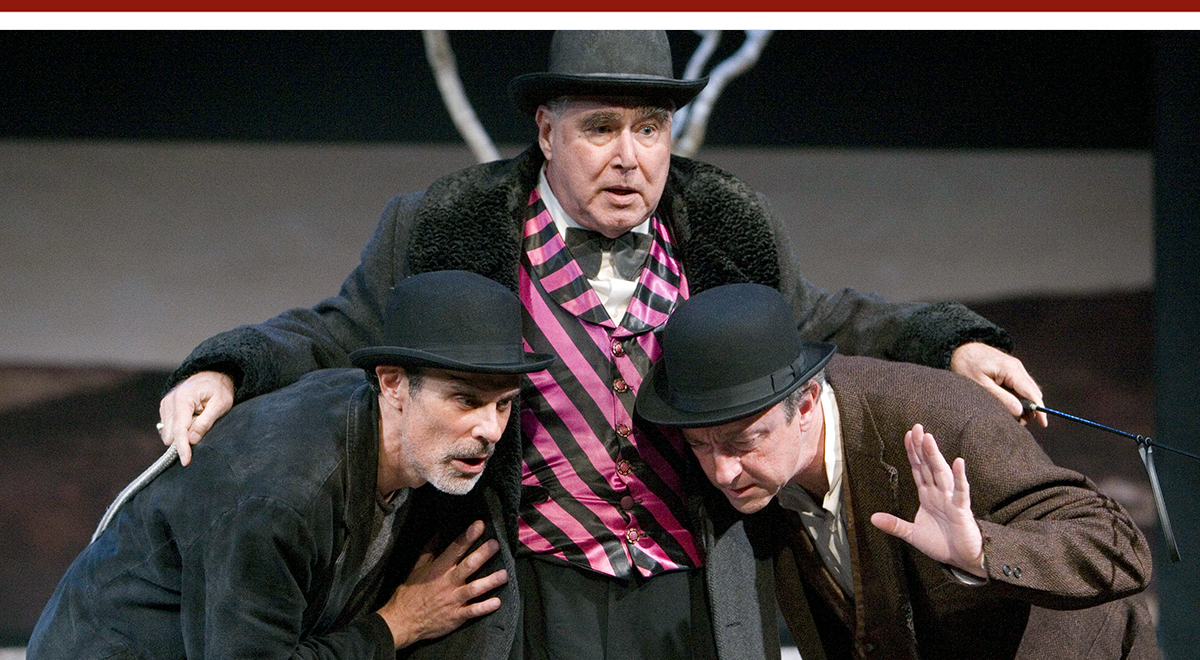

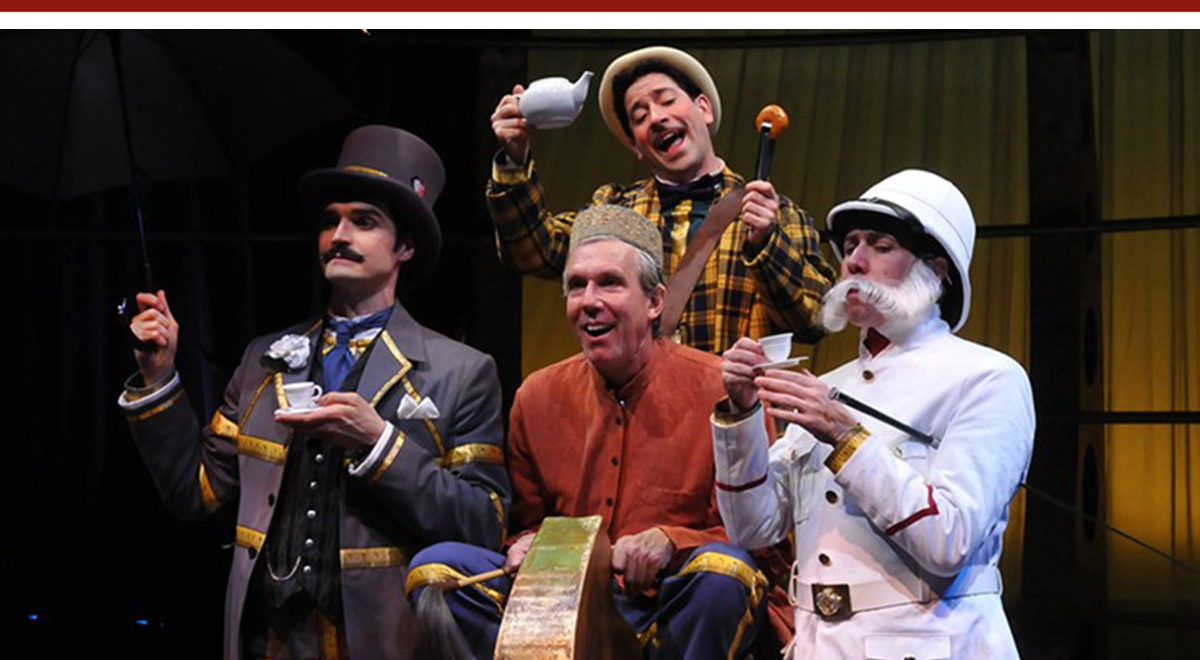

Anna Bullard, Howard Swain, Matthew Floyd Miller, Gendell Hernandez and Mark Farrell / Pat KirkMatthew Floyd Miller, Gendell Hernandez (top), Mark Farrell and Howard Swain

Laguna Playhouse

Kid Charlemagne

It’s not that Pippin, Stephen Schwartz’ modest 1972 musical, ultimately has nothing to say. It’s more that the contradicting themes in Roger O. Hirson’s book either cancel each other out or dissipate in the air of a tossed-off “anecdotal revue” (to quote the rousing opening number). The Center Theatre Group and Deaf West Theatre have supercharged a slightly re-envisioned version, in hopes that lightening again will strike their Mark Taper Forum co-production (through March 15), as it did when the companies revived Roger Miller’s Big River in 2002.

Director Jeff Calhoun has assembled an exceptional cast and design team and found in Steven Landau an arranger/musical director who can make the score pulsate with currency and still keep its early ‘70s sensibility. He also enlivens his staging with plenty of inventive touches. This surely provides the ballast needed to float this boat to Broadway. Whether, once there, it takes on profit or water is an open question.

When the original Pippin opened in October 1972 (not counting the Harry Beckett-Michael Connelly Broadway musical that opened and closed in April 1870), the country was divided by war and about to re-elect a President of Shakespearean flaws. Eight days before first preview, The Washington Post had reported that the FBI had discovered “a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of President Nixon's re-election.”

This musical about a rights-trampling, war-waging leader found audiences more than receptive. Today’s audiences are just as ready. (Though we’d like to think we turned a page with the inauguration a few days before opening.) The problem isn’t topicality, but that the various structural conceits and messages, while layering the piece with cleverness, have dulled the impact.

The over-arching context is of an acting troupe presenting a series of morality tales within the framework of a nightclub magic show. With Deaf West’s involvement, signing becomes a welcome presentational element with great potential for added metaphor (though the metaphors that develop here are eventually undercut, too). Another storytelling level is added by having the person who plays Pippin be alien to the show business world. He is pulled from the house as if chosen at random for that performance. We now have a fictitious person entering a make-believe world that will draw from world history to ultimately present a variation on the simple message, “There’s no place like home.” It’s all a little mangled. As with Big River, this device not only celebrates the inclusion of the often-marginalized deaf audience, it sparks some of Calhoun’s finest ideas. The early dividing of the character of Pippin into two actors (Michael Arden speaks, Tyrone Giordano signs) is a wonderful – but sadly unique – merging of all the show’s worlds.

Thirty-six years ago, the musical came during director/choreographer Bob Fosse’s heyday and was the first Broadway show that opened with Ben Vereen in a key role – the Player (here performed with power and seductiveness by Ty Taylor). Vereen’s unique ability to beam his out-sized personality to every seat in the house helped align the script’s shifting weight behind his character. That talent, and Fosse’s, along with the times, made theater history – winning Tonys for both men and making the opening “Magic to Do” a fixture on Broadway Best Of Collections.

In Pippin our guest-actor Guinea pig is sent down a gauntlet of placard-introduced scenes for lessons in “Sex,” “Romance,” “Humor,” and so on. The first two thirds of them involve the history-based world of “Pepin,” son of Charles I (Troy Kotsur, with Dan Callaway providing the voice). Also known as Charlemagne, this 8th Century emperor united virtually the entire Christian world as the Holy Roman Empire, waging brutal military campaigns as he fostered cultural advances. His son, by most accounts a hunchback, was borne of his fourth wife, Fastrada (Sara Gettelfinger), who maneuvers her other son, Lewis (James Royce Edwards), into line for succession. Floating around court is Charles’ mother, Berthe (Harriet Harris), to provide additional perspective. Pippin will briefly remove and replace his father on promises of an enlightened reign, only to find – in a curious defense of heavy-handed leadership tactics – that there is good reason why leaders are so insensitive to the common man. Suddenly our Storybook is leaning towards the pages of National Review. Immobilized by the pressures of leadership, Pippin magically brings his dad back from the dead, hands him the reins, and moves on to more lessons that bear no apparent connection to the court of Charlemagne.

To promote domestic tranquility, he is given a taste of the ordinary life with the young widow Catherine (Melissa van der Schyff) and her son, Theo (José F. Lopez, Jr., alternating with Nicholas Conway). He first tires of them, then is drawn back to them. And just when we think the message has focused on the importance of the un-extraordinary, the creators can’t resist a final coda to acknowledge the enduring lure of magic, specifically of the theater. While the presence of Arden/Giordano, Taylor, Gettelfinger, Harris, van der Schyff and the others make this a wholly satisfying and engaging experience, in the final analysis, there’s clearly less in the lesson than planned.

top of page

PIPPIN

book by ROGER O. HIRSON

music and lyrics by STEPHEN SCHWARTZ

musical direction and arrangements by STEVEN LANDAU

directed and choreographed by

JEFF CALHOUN

MARK TAPER FORUM

January 15-March 15, 2009

(Opened, rev’d 1/25)

CAST Michael Arden, Jonah Blechman, Dan Callaway, Bryan Terrell Clark, Nicolas Conway, Rodrick Covington, James Royce Edwards, TL Forsberg, Sara Gettelfinger, Tyrone Giordano, Harriet Harris, Rebecca Ann Johnson, Troy Kotsur, José F. Lopez, Jr., John McGinty, Anthony Natale, Aleks Pevec, Victoria Platt, Ty Taylor, Nikki Tomlinson, Melissa van der Schyff, Alexandria Wailes

PRODUCTION Tobin Ost, set/costumes; Donald Holder, lights; Philip G. Allen, sound; Jim Steinmeyer, illusions; Carol F. Doran, hair/wigs; Linda Bove/Alan Champion, ASL masters; Tom Kitt, orchestrations; David Sugarman/Brian J. L’Ecuyer/Jennifer Brienen, stage management

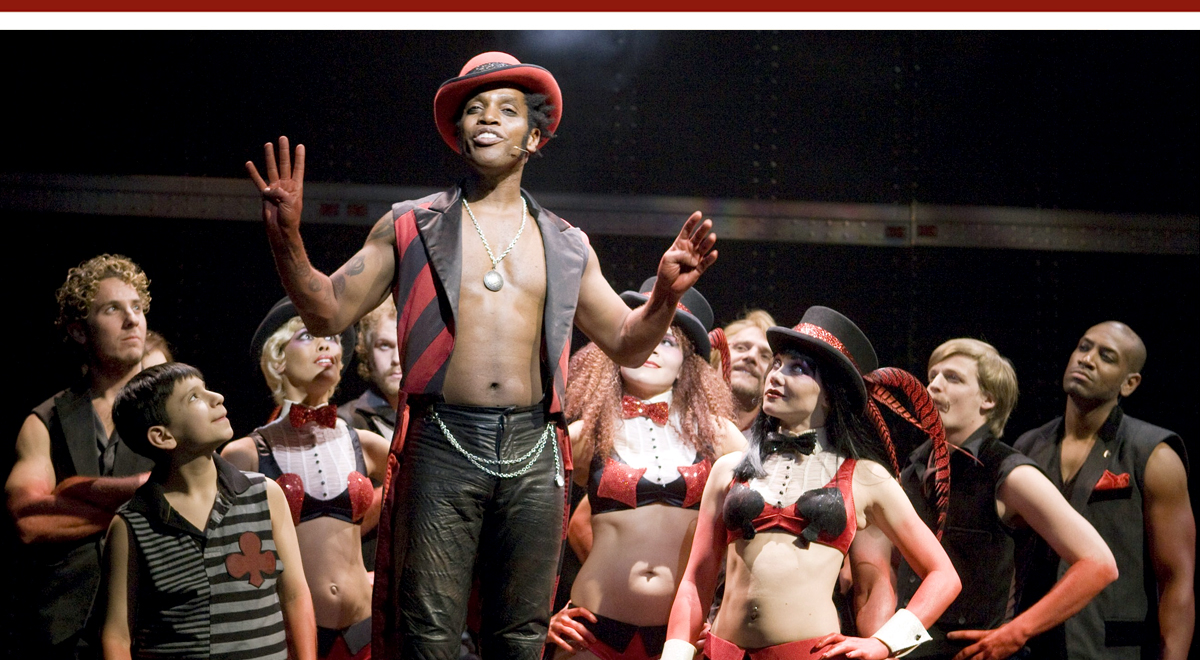

Ty Taylor, center, and cast

Craig Schwartz

Horne of Plenty

Those who have not experienced Lena Horne in real-time, lighting up torch songs or disarming interviewers with the gloved fist of a playful lioness, may mistakenly come away the Pasadena Playhouse’s current production of Stormy Weather (through March 1), thinking she was a bitter woman and begrudging ground-breaker.

Still with us at 91, Horne was one of the 20th Century entertainers who, helped break the color bearer that stretched across every aspect of show business. In the tradition of Ethel Waters (who had an earlier hit recording of the tune that gives the show its name), Horne sang her way to fame in nightclubs, and on bandstands, stages, recordings, and finally film and television. Compared to Waters, born to a poor 12-year-old and a white rapist, Horne was middle class. Her educated parents combined an ethnic mix of black, white and Native American that gave Horne a stunning hybrid beauty that even white producers wanted a piece of. Though it took decades, eventually the logic echoed in Lenny Bruce’s famous “White Woman, Black Woman” routine (which references Horne’s charms) won out, and she, among other achievements, became the first African-American to sign a major contract with MGM. Though not in the top rank of singers like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holliday or Sarah Vaughn, Horne was still a great singer. With her acting talent, her beauty, intelligence, and a sense of empowerment gained from enlightened parents, she was strident enough to push the social envelope in ways those other could not.

With Leslie Palmer and Nathan Huggins’ Lena Horne, Entertainer as a guide, Stormy Weather conceiver-writer Sharleen Cooper Cohen has shaped Horne’s life into a two-and-a-half hour bio-play. There are 26 musical numbers, most of them Great American Songbook entries associated with Horne. Cohen structures her script as flashback from the time around 1980 that she was deliberating whether to put her life on stage in a one-woman Broadway show. She did, of course, and earned both Drama Desk and Grammy Awards for it.

Unfortunately, the script feels hackneyed, clinging to heartbreaks and offering little to clarify what made this major artist so unique. In interviews – like the “60 Minutes” segment Ed Bradley considered his career highlight – she comes across as both steely and sensuous. That balance is missing here, especially during scenes with the elder Horne, played by Leslie Uggams. Uggams spends virtually the whole show on stage, watching the events and occasionally jumping back into the action to provide moral support and perspective to her younger self, played by Nikki Crawford. When her intrusions prove too much for Crawford’s younger “real-time” Horne, the frustrated daughter-mother parallel is a real – though rare – bonus of the show’s structure.

However, because Cohen and director Michael Bush want that sense of bitterness to be ever-present, Uggams must spend much of the show with a scowl. Even her opening number, “Love,” feels oddly subdued and distant. Uggams is not a great actress and she is unable to break through the layer of stoic resolve her writer and director have paved over her quiet moments. Her many scenes with devoted friend Kay Thompson (Dee Hoty), feel repetitive.

The rest of the cast is good in support, with the main standout being Crawford, who despite being a little betwixt and between in terms of imitating Horne or being her own belter, nevertheless delivers the show’s big musical numbers with great appeal. Also noteworthy are Hoty as the long-suffering but always cheery pal, Kevyn Morrow as a beautiful Billy Strayhorn, and Robert Torti as arranger Lennie Heyton, Horne’s second husband. Also, Wilkie Ferguson and Phillip Attmore fill in several roles, notably as dancers who provide a show-stopping tap routine that, despite becoming a little frayed at the finish, was dazzling.

The move to split the Horne character between two actresses is a good one. Watching herself provides the character with opportunities to reflect. And the way Cohen changes the way in which the elder enters earlier scenes sometimes seen, sometimes not, sometimes vocal, sometimes merely shaking her head in disbelief, is one of her best inventions, giving the show a needed freedom.

The play’s heart may lie in a couple moments in the second act. Uggams’ shows us Horne’s turning point in the singing of “Honeysuckle Rose.” After declaring she would no longer sing as an imitation white women, she turns the song inside out and moves light-years ahead of singers like Waters and her generation. Though the effect is somewhat buried after we’ve endured so much generic squabbling, the show has found its compass coordinates. A rousing, if predictable Gospel version of “This Little Light of Mine” follows, with another of Uggams’ better efforts, “Yesterday When I Was Young,” extending her exposure of the real woman.

Crawford’s finest moment comes next, with Horne in the oversized shirt and slacks (costumes by Martin Pakledinaz), seething her way through a version of “Love Me or Leave Me.” This is that ‘60s crucible of change that would have been wonderful to spend more time in, exploring Horne’s life from this historic turning point for her and us. Even Bush’s move to split up Crawford’s great performance by inserting another argument between Uggams’ Horne and Heyton does not diminish it. The show received enthusiastic reviews in its Philadelphia premiere in 2007 and may well here. Clearly headed for Broadway, it really only serves as a starting point to appreciating Horne. Be sure to check out her dvds of her work, too. And, find that Ed Bradley interview. You’ll get two – willing – ground-breakers for the price of one.

top of page

STORMY WEATHER

bySHARLEEN COOPER COHEN

musical direction by LINDA TWINE

choreography by RANDY SKINNER

directed by MICHAEL BUSH

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

January 21-March 1, 2009

(Opened, rev'd 1/30)

CAST Phillip Attmore, Jordan Barbour, Yvette Cason, Nikki Crawford, Cleavant Dericks, Wilkie Ferguson, Ashley Greene, Dee Hoty, Bruce Katzman, Cheri McKenzie, Kevyn Morrow, Jeffrey Rockwell, Robert Torti, Toni Trucks, Leslie Uggams, Diane Vincent

PRODUCTION James Noone, set; Martin Pakledinaz, costumes; Paul Gallo, lights; Lewis Mead, sound; Paul Huntley/Carol F. Doran, hair and wigs; Gordon Goodwin, orchestrations; Rrandy Skinner, choreography/dance arrangements; Linda Twine, conductor; Lurie Horns Pfeffer/Lea Chazin, stage management

Leslie Uggams

Kevin Berne

Return to Forever

Samuel Beckett's Waiting For Godot, a surprise hit for A Noise Within in Andrew J. Traister’s well-cast, well-paced 2008 staging, has proven itself a worthy re-mount. And, with word from someone associated with the show that it could have sold a third week, it seems a viable follow-up to Arthur Miller’s The Price as an annual "special engagement" midway through the six-play season.

Godot has been called the most important play of the 20th Century. One reason is the precision, even terseness, with which the play seems to be saying nothing, yet opens worlds of often ambiguous meanings about the most fundamental concerns of life. It is no less than the playwriting equivalent of sorcery.

From its opening beat – “Nothing to be done” to “Nothing to show” – we hear a nihilist’s eye-view of a human life. The characters, in their bowler hats and baggy pants, are unaware of their own profundity. Near the end, another character sums up a lifetime as a drop from womb to tomb. The importance of chance, and even the odds that any given event will occur, are employed by Beckett to give balance to the void. There are repeated examples of this: Vladimir weighs the percentages that one of the two men crucified alongside Christ was a thief; there is equal chance that the radish or carrot, or radish or potato will be pulled from his pocket; Gogo says “He might have been in my shoes and I in his, but chance ruled otherwise”; and, in one to charm the mathematician in us all, Didi ruminates on whether he is heavier (to determine who should hang himself first). There’s an even chance . . . . Well almost. (The allowance for that tiny percent chance that their weights are equal is a surprisingly astute observation for a clown.)

That we can discover and relish such pleasures within the script is further proof that Traister and company have done their work well.

There have been minor changes, according to inside info, but the only change I noticed, and it may be a mirage of memory fog, was that Mitchell Edmond’s Pozzo was less broad. If that in fact is a directorial change, it is understandable, as it brings the production more into alignment. However, the bigger laughs were certainly permissible in a play so in tune with clowning.

The cast remains the same. In addition to Edmonds, Joel Swetow is back as Estragon (Gogo), Robertson Dean as Vladimir (Didi) and Mark Bramhall as the downtrodden Lucky, whose one speech and modern dance (can it be an interpretation of climbing out of the grave?) are highlights. Alex Yeghiazarian plays the young brothers.

It is also good to see a Michael Smith/Angela Calin design combination. Smith, the company’s great set designer, was not involved in Hamlet, which could have used him, or The Rainmaker or Oliver Twist. (Though Kurt Boetcher’s set for Twist was brilliant.)

There are good reasons why Waiting for Godot is cited as a masterwork of theater, yet none are going to hit viewers over the head. Repeated viewings are essential, and if A Noise Within makes this an annual event for the next few seasons, locals are advised to make it, to invoke Wilde, “their constant study.”

top of page

WAITING FOR GODOT

by SAMUEL BECKETT

directed by ANDREW J. TRAISTER

A NOISE WITHIN

September 19-November 8, 2009

(Opened, rev’d 10/3)

CAST Mark Bramhall, Robertson Dean, Mitchell Edmonds, Joel Swetow, with Alex Yeghiazarian

PRODUCTION Michael C. Smith, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes