JULY 2006

Click title to jump to review

AND THE WINNER IS by Mitch Albom | Laguna Playhouse

CHRISTMAS ON MARS by Harry Kondoleon | The Old Globe

GOD OF HELL by Sam Shepard | Geffen Playhouse

LITTLE EGYPT by Lynn Siefert and Geoff Henry | Matrix Theatre

MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN by Bertolt Brecht | La Jolla Playhouse

SLOW DANCE ON THE KILLING GROUND by William Hanley | Athena Theatre / The Lounge

TICK, TICK . . . BOOM by Jonathan Larsen | The Coronet

THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE by William Saroyan | The Open Fist

WITHOUT WALLS by Richard Greenberg | Mark Taper Forum

O

At a loss

O

The title page credit for the West Coast premiere currently at the Laguna Playhouse (through July 2) reads "Mitch Albom's 'And the Winner Is' by Mitch Albom." The stutter-billing underscores the importance of the author, who wrote 'Tuesdays with Morrie,' a feel-good novel that drew Oprah's endorsement as well as TV and stage adaptations that earned an Emmy and a sold-out Laguna Playhouse run, respectively. Or, it may just be the result of a meddlesome agent, taking his cue from this play about a meddlesome agent's excess.

When the house lights first fade, to a '50s tune, the sound of breathing begins to rise, then divide into gasps that echo and divide again until the auditorium is choking on David Edwards' superb sound design. Sudden silence as Paulie Jenkins' lights reveal John Berger's formidable set, a proscenium-spanning dilapidated saloon that has been boarded up from the inside. Toppled tables and chairs clutter the floor around the open mouth of an immense laundry chute-ventilator shaft that disappears up into the fly space. Just as we notice the back of a gray-haired man at the counter, hunched over some reading material, a half-dressed man falls from the chute onto the pile of mattresses and soft-trash beneath its opening.

An auspicious start. However, once the new arrival speaks, the delicate air of mystery created by the design team is gone.

Tyler Johnes (Kelly Boulware) has died in his sleep the night before an Academy Awards ceremony. Worse than that, he's been dumped into this tweener-bar purgatory, rather than joining the rest of the night's deceased outside it, because he didn't maintain the reciting of a childhood bedtime prayer. Worse still, he's up for an Oscar this year, for a role in a war-themed art film. But worst of all is that Johnse's nomination for Best Actor means that, not only has the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences finally lost its way, so has this play. Winner traces its bloodline to the fantasy fields where Here Comes Mr. Jordan/Heaven Can Wait, It's a Wonderful Life, A Christmas Carol and others live. However, just 'cause they're fantasies doesn't relieve them of the requirement of abiding by their own internal logic. For instance, can the dead go back for a visit to see the world they left? If so, will they be visible? Can they communicate with others, be touched, etc? Might they be able to alter history to prevent their own deaths?

If such a rulebook for Winner exists, it must be lost amid the set's clutter. Albom seems to adjust the world of his play to fit the jokes.

Tyler Johnse, a stage name that replaced "Jake Steinberg," embodies all the easy clichés about screen and TV actors. In flashbacks we see Steinberg tell his young wife (Ann Marie Lee) platitudes about the importance of theater as he somehow gets cast as Richard III. Apparently, before he can be fitted for a hump, he's ready to take up with a fast-talking agent (Jeff Marlow), change names, dump the stage route and the marital fidelity, and pursue a film career and all that comes with it. He reaches the red-carpet stardom he holds at his passing through a cop-film franchise about crime-fighting Chippendales dancers that co-stars Kyle (Brent Schindele), a rival off-screen Lothario and (just to keep plotting easy for us) another Oscar-nominee for the same war film. For years, Tyler has accused Kyle of seducing his wife away, despite protestations from both of them. But Johnses leaves her without ever discussing the matter intelligently.

But then intelligent discussion is not what weíve signed up for here.

In deference to the play's comedy, Boulware and director Andrew Barnicle want to make sure Tyler's self-obsession is unmistakable. That translates to a pretty one-note performance that, particularly in the opening exchanges, is a very loud note. The old cliché about athletes giving 150 percent now has a theatrical equivalent as Boulware works at that overage. And it's not a pretty sight. Lots of fuming, lots of gesturing, lots of shouting. Little coloring. When he sits at the bar table, his right leg bounces away uncontrollably, an enervating disorder for the performance.

As Teddy, Marlow hints at deft comic timing and nuance. Unfortunately, that is undermined by the required Clousseau-style French accent that must be ladelled over his speech like Bernaise a-sousz. Nicolas Coster plays Seamus, the "Clarence" in this story, and does the best he can with what he's given. Lee is affecting as the main person with whom Tyler must make amends. Thanks to her ability to escape the Comedy Demands and stay grounded during the whole show, the characters of Johnes and Sheri are able to hog-tie this beast and drop it for a moment of tenderness before the final curtain. But, like much of the effort, it still falls flat. A sixth character, or caricature, is the walking pin-up, Serenity (Annie Abrams), who – as one wag noted – gives the whole evening the up-to-the-minute consciousness of a Dean Martin Gold-diggers' sketch.

top of page

AND THE WINNER IS

by MITCH ALBOM

directed by ANDREW BARNICLE

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

May 30-July 2, 2006

CAST Annie Abrams, Kelly Boulware, Nicolas Coster, Ann Marie Lee, Jeff Marlow, Brent Schindele

PRODUCTION John Berger, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Paulie Jenkins, lights; David Edwards, sound

HISTORY West Coast Premiere

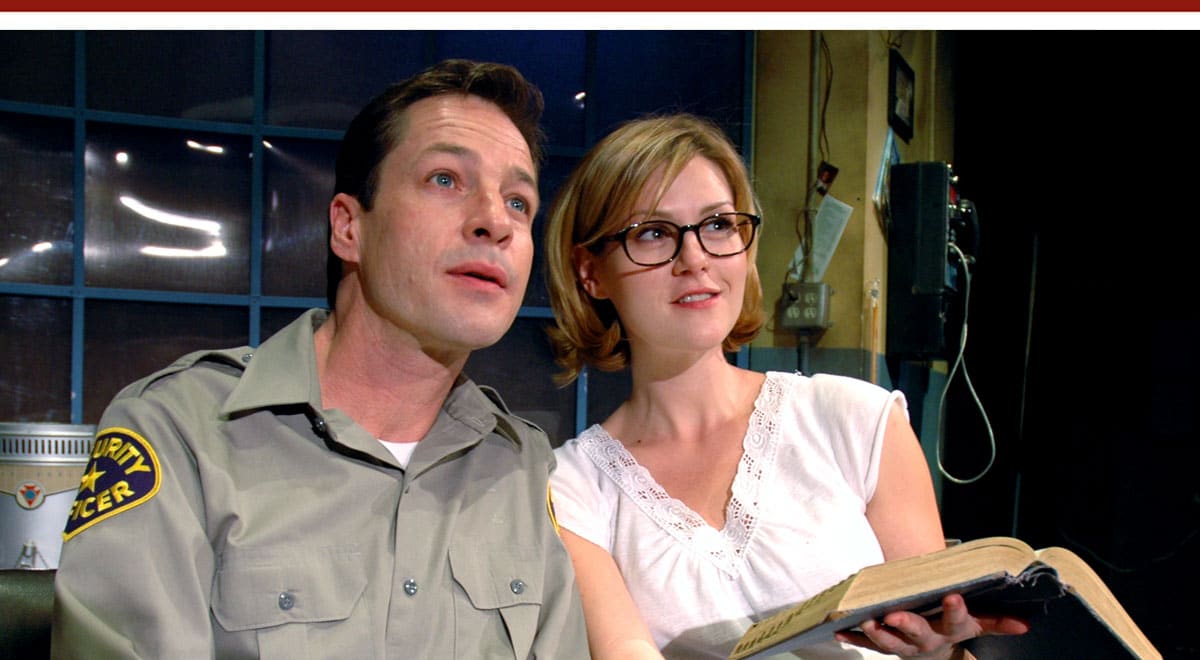

Nicolas Coster, Kelly Boulware

Ed Krieger

O

Alien sighting

O

Playwright Harry Kondoleon died in 1994 at the age of 39 having published 18 plays and a volume of poetry, but only one of many novels he is said to have written. Its title, Diary of a Lost Boy, provides a haunting context for the final images of Christmas on Mars, a 1983 script introduced to the West Coast at South Coast Repertory that year and now in revival on the Old Globe Theatre's Cassius Carter Stage through July 9.

In newspaper interviews director Kirsten Brandt says she hopes to serve the play with her staging, and the signs that she indeed has approached the prickly script with kid-gloves are evident. Brandt properly plays Kondoleon's central theme of a personal alienation so severe that it might as well be inter-planetary. But she allows – or prompts – one performance so disastrous that it is the theatrical equivalent of a suicide bomber. And although the production is far from destroyed – in fact, it remains worth a look for anyone curious about Kondoleon – a gaping hole has been blown into it.

The play takes place in an unfurnished apartment that, in Act I, Bruno (a solid David Furr) is showing his girlfriend Audrey (Sarah Grace Wilson) as part of a marriage proposal tied to co-habitation. Bruno, an actor-model trading on good looks and Audrey's position in commercial casting, has also arranged for them to meet her estranged and despised mother, Ingrid (Colette Kilroy). He's hoping the apartment, his charms, and the impromptu mother-child reunion will convince Ingrid to loan him a down payment. Breaking in before Audrey arrives is Bruno's needy roommate Nissim (Jack Ferver), who has chosen this time and place to ambush his friend of more than a dozen years and disclose suspicious information about their relationship. He hopes it will frighten Audrey away.

We soon realize that nothing anyone says can be taken at face value; what Audrey has told Bruno about Ingrid is denied; what Nissim says about Bruno seems absurd; and what each character says about themselves sounds fabricated. Soon, Audrey even doubts Bruno's love.

Kondoleon created a world in which despair is the default emotion and happiness the one we hunt and gather from scratch each day. His characters are developed from the outside in, through blasts of hyperactive poetry that propel the simple plot. The characters' unreliability is part their basic instinct to hide the void at their core. Eventually they can't tell the difference between what's real and what's made-up; between what they want and what they need. All of this makes the actors' job of understanding each exchange harder and the play is prone to feel wobbly as styles and moments seem to bear no relation from one minute to the next. Ultimately, however, there is a grace to the people on Kondoleon's planet, a nobility of the doomed. It pushes each character to try and fill those elusive needs in the most colorful, endearing and poetic ways, and communicate their misery in lines like, "I feel like a contusion; banged around in the night; blue with the truth."

Regarding the "comic-kazi": The better written a crazy person is, the less an actor needs to play the craziness. T. Scott Cunningham in The Violet Hour is convenient proof (see review). Here, while Nissim gets the lion's share of Kondoleon's rants, and would seem to be his stand-in, he is in truth no healthier than anyone else. Furr manages to get laughs playing it straight, as do the sadly beautiful Kilroy and doeful, damaged Wilson, who slyly adjusts from blankly depressed in Act I to generally pleased in response to Act II's skewed domesticity. But Ferver plays it for all it's worth, like a comic who has tried everything and is now desperate, with barrage of eye-widening and face-wrenching excess. Nissim's unbearable bearing undermines one of the play's basic tenets - the length of his relationship with Bruno. (Again by comparison, the believability of the Gidger-Seavering relationship in Violet Hour helps us focus on more important matters.)

What emerges is an appreciated revival of an under-appreciated playwright, with an appreciable hole at its center.

top of page

CHRISTMAS ON MARS

by HARRY KONDOLEON

directed by KIRSTEN BRANDT

THE OLD GLOBE

June 8-July 6, 2006

CAST Jack Ferver, David Furr, Colette Kilroy, Sarah Grace Wilson

PRODUCTION Nick Fouch, sets; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes; David Lee Cuthbert, lights; Paul Peterson, sound

Colette Kilroy, Sarah Grace Wilson, Jack Ferver (seated) and David Furr

Craig Schwartz

O

Off the grid

O

'God of Hell,' at the Geffen Playhouse in Westwood through July 30, is Sam Shepard's searing burlesque of our drifting ship of state and the new breed of helmsman driving it further into the rocks. Shepard returns us to the scene of his previously chronicled crimes, a lovingly drawn Midwestern farmhouse. But the days are gone when the worst life could throw at us was death.

The perennial farming nemeses of disease, weather and forced subsidization are overshadowed by more invasive threats of government agents, brainwashing techniques and free-range radioactivity. Threats of nuclear proliferation a generation ago were more remote. Now, suitcase bombs of Plutonium – a substance that gets its name from the God of Hell – are a reality. And while the terrorists who will use them are insane, the people protecting us may be clowns. "Did you think you could enjoy this wanton freedom without any cost?" one character demands of another. Good point. Except that we have paid and continue to pay for our freedom with thousands of young lives and trillions of taxpayer dollars. The question should be, "Did you really think the leaders you elected are worried about what happens to you!?"

The story begins at sun-up, as Frank (Bill Fagerbakke) is suiting up for a day tending his dairy herd and Emma (Sarah Knowlton) is preparing her daily over-watering of the house plants. After the morning broadcast of the national anthem (which Frank observes but does not stand for), Emma anxiously asks if she can wake their houseguest, Mr. Haynes (Curtis Armstrong). Haynes is an old acquaintance of Frank's who is temporarily sleeping in the basement. Once Frank has left, Emma has a visit from a stranger named Welch (Bryan Cranston). Dressed with patriotic accessories, bounding around like a superball and pulling a small gift shop from his magician's briefcase, Welch is dismissed as an annoyance. But he returns several times until it is clear he is an agent of the government tracking an exposed nuclear worker, who is Haynes.

Shepard is skewering the new political style as much as its substance. This is a fair exchange, given how interchangeable style and substance have become. The U.S. government is represented by salesman-politicians who win the hearts and minds of citizens with jingoistic gibberish that passes for leadership. To make this blunt message easier to swallow, Shepard wraps it in a cloud of laughing gas and has Jason Alexander – in his directorial debut – stage it. Alexander, who is a star performer in theater and television, knows the first rule of directing is casting and he's employed a quartet of actors who, like himself, know how to work the big stage as well as the little screen.

This is a tough first assignment, however, as it's a play that wants its gut-punches to land as belly laughs. Not surprisingly, neither goal is fully achieved. For the belly laughs, Alexander relies more on comedy tricks from the Producers end of the spectrum. There is also subtlety, but it's more or less lost in the production's big comedy devices: exploding lights, sparking torture effects, and a tedious running gag in which a mooing sound is milked to the point of gagging. Ironically, its pay-off, in which a thunder roll indicates the cows are now lowing from on high, goes right over our heads.

This should not be confused with the acting, which rides the line of normalcy and excess pretty convincingly. That is, except for Cranston's performance, which is what gives this show its value. This is a role that clearly comes with an official union scenery-chewing license. And Cranston does that, but somehow he earns the excess and takes his curtain call without having left a single bite mark on John Iacovelli's set. Shepard and Alexander are lucky to have him at the center of this farce. Cranston is a very polished actor. His excesses are completely in control, as he carefully shifts from manic showman to brainwashing executioner without breaking character. One recognizes so many of our chuckling leaders in Cranston's comedy. Then, just when you feel he's benign, the mask drops just enough to reveal the monster. Immediately he snaps back to the smiling, shining person we're used to in campaign advertising and used car commercials. His Janus profile parallels the plays namesakes: Pluto the cartoon character and Pluto the radioactive element are named for the same god.

Post script: It was eerie to see Alexander wearing the same old Glory tie Cranston wears when he hosted the "Capitol Fourth" broadcast last Tuesday.

top of page

GOD OF HELL

by SAM SHEPARD

directed by JASON ALEXANDER

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

June 21-July 30, 2006

(Opened 6/28, rev'd 7/1)

CAST Curtis Armstrong, Bryan Cranston, Bill Fagerbakke, Sarah Knowlton

PRODUCTION John Iacovelli, set; Christina Haatainen Jones, costumes; Jason H. Thompson, lights; Jon Gottlieb, sound; Mary Michele Miiner, stage management

HISTORY Premiered in 2004. West Coast Premiere

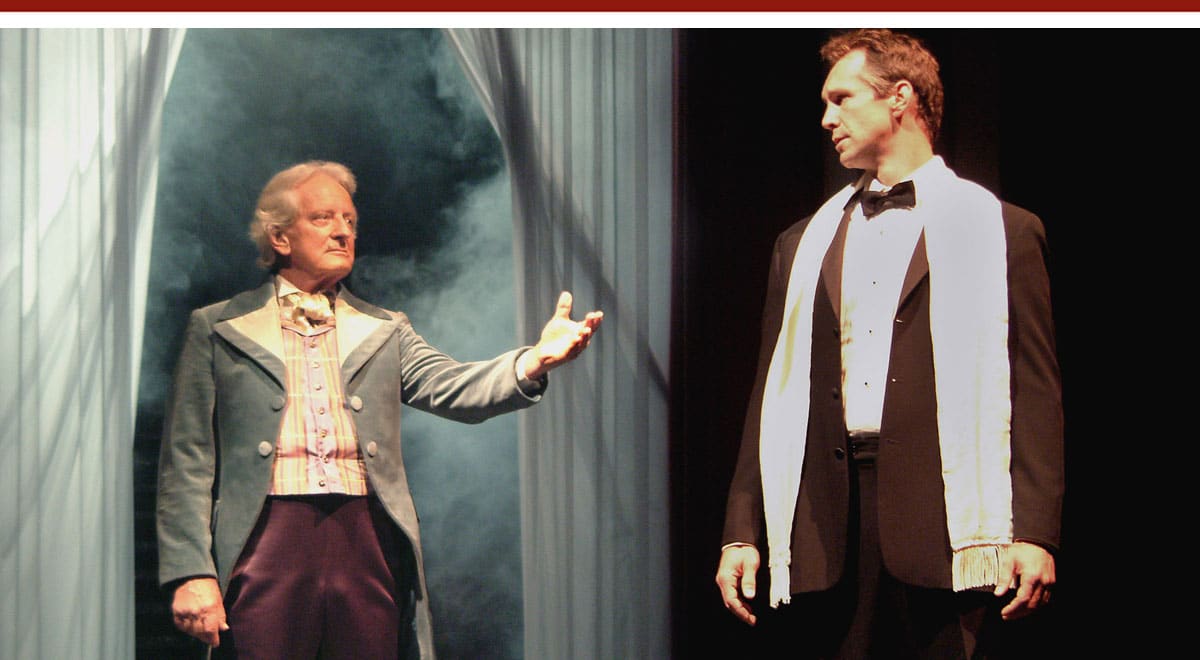

Sarah Knowlton and Bryan Cranston

Michael Lamont

O

Nerds in love

O

The confluence of three rivers help define the shape of Illinois’s lower quarter. That area earned the nickname ‘Little Egypt’ after prairie folk arrived in a migration of biblical proportions caused by the 1830 drought. That region is now the inspiration of a crazy new musical that is the confluence of three talented theater artists: playwright Lynn Siefert, composer/lyricist Gregg Lee Henry, and director Lisa James.

Little Egypt offers its own welcome escape thanks to a strong score and a top cast just inches away in the intimate Matrix Theatre. There is some turbulence downriver, however, when the script moves into the darker waters of the second act. Continuing in an extended run through June 25, Little Egypt is a worthwhile excursion for a screwball love story set amongst small-town nerds, brutes and misfits, and a refreshing break from theater about theater people.

Director Lisa James has a lot of power to unleash on this world premiere in a cast of French Stewart, Misty Cotton, Sara Rue, composer Henry, Jenny O’Hara and John Apicella.

The plot is an anarchic take on boy meets girl, set seven years after the end of the Vietnam War, wherein lies the weighty back story that surfaces late in the play to nearly sink this towering blancmange of musical farce.

Victor (Stewart) and Watson (Henry) are old comrades in arms who are having trouble gaining traction back in their tiny town. Victor is a poorly paid mall security guard who loves his work but can only afford to live in an abandoned service bay. His sweet devotion to the cruel and manipulative Watson grows harder and harder to fathom, especially after it threatens his one-shot-in-a-million romance with Celeste (Rue), a quirky beauty who is the village idiot savant.

Back from college, she’s dumb enough to report when asked about meeting ‘Mr. Right’ that she "didn’t meet anyone with that name." Celeste has sought shelter from the norm with her waitressing mother and sister (O’Hara and Cotton), who are usually in the pink uniforms of their white trash diner. They get the play’s hilarious, over-the-top ‘trash farce’ style up to racing speed when an early argument tumbles into a wrestling match that quickly melts into hysteria.

Celeste, on the other hand, is given to wrestling only with questions of arcane science, and laughing in a kind of snorting seizure that Rue manages to make look adorable. Apicella plays the town’s mayor, giving Celeste’s single mother a love interest – and the show the subject of its Act II opening number. Unfortunately, this character's deeds and misdeeds don't stand much analysis so we'll scrutinize that subject not.

There’s an art to farce and for the most part these guys have it. Stewart and Rue have characters who are equally ridiculous and endearing, and they serve them well. The others combine a screwball side with a range of other traits -- mean, brassy, tarty, philandering, etc. -- and do them well within the script's demands. Stewart thankfully shows he has more oars onboard his craft than the alien antics of his “Third Rock” TV persona. The singing voice he adds to the strong vocals could out-chart Keith Carradine. Misty Cotton is a force of nature I’m embarrassed to say I’d only seen perform at the Robby Awards, which ain’t prime time.

Henry again displays the rock-roots chops he showed off back in the 2000 world premiere of SCR’s musical of Randy Newman tunes – whose style is echoed at least once in this show's "Nobody’s Immune." Henry’s music is always engaging and his lyrics can be quite poetic, as in Celeste’s beautiful "Fishing for the Moon" (paraphrased, unfortunately, but you get the idea: "I used to want you to dance to my own tune, but so much water under all these blackened bridges has me fishing for the moon"). That song is but one example of how Henry and Siefert employ the rivers as agents of various forms of departure. For the first act, the mixture of farce, heart and music is pure joy.

Once we’re into Act II, however, when the waters need to flow to an end point, the plot’s arteries start to harden and Victor’s dark secret lands like a drunk guest on a birthday cake. Victor’s survival instincts need to come to the fore a little earlier and clearer. His final visit to the river won’t be compromised if it gets a little backbone earlier. He'll still fulfill the ‘Boy Loses Girl’ part of the equation by showing the snorting darling he really can stand up for her.

top of page

LITTLE EGYPT

book by LYNN SEIFERT

music and lyrics by GREGG LEE HENRY

directed by LISA JAMES

MATRIX THEATRE

through June 25, 2006

CAST John Apicella, Misty Cotton, Gregg Henry, Jenny O’Hara, Sara Rue, French Stewart

PRODUCTION James Carhart, set; Vicki Sanchez, costumes; J. Kent Inasy, lights; Brian Mohr, sound; John Lathan, vocal arrangements; Robert Martin, musical director (other musicians: Eric Heinly, Andre Holmes, Kevin Tiernan)