JUNE 2013

Click title to jump to review

HIS GIRL FRIDAY adapted by John Guare | La Jolla Playhouse

WILD IN WICHITA by Lina Gallegos | Bilingual Foundation of the Arts

Left at the altering

The La Jolla Playhouse has launched its 2013 Season with the West Coast premiere of His Girl Friday, John Guare's 2003 "marriage" of the 1928 stage comedy The Front Page and His Girl Friday, its 1940 screwball-comedy film adaptation starring Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell.

After numerous stagings, beginning at the commissioning National Theatre in London, Artistic Director Christopher Ashley's capable cast provides an opportunity for Southern Californians to assess why this Girl Friday has failed to earn the glowing performance reviews its sources received. Is it ill-conceived, or routinely miscast? Or both?

In the large Mandell Weiss Theatre (through June 30), Ashley's leads are Douglas Sills, the Tony-nominated star of the Scarlet Pimpernel, and Jenn Lyon, a rising star whose pin-up glamour is backed by razor-sharp comic timing. Around them, the large cast includes a strong top tier of Donald Sage Mackay, Patrick Kerr, Bethany Anne Lind, and Matt McGrath. They provide plenty of rewarding moments, which suggests Guare's trouble lies not in his stars, but in his script.

Guare inherits some genetic defects from his source material. Conflicts in tone and purpose challenged The Front Page and would have fried Friday were it not for the otherworldly appeal of Grant, and his exceptional chemistry with Russell. In both cases, however, the comedy kept the commentary in check. Guare has deepened the messaging in a way that balances the comedy and commentary, neutralizing the impact of both.

Based on their years as Chicago newspapermen, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur set Front Page in the press room of the Chicago Criminal Courts building. Hildebrand "Hildy" Johnson announces he's quitting his paper to get married. It's the day before the execution of Earl Williams, convicted of killing a black policeman. Johnson's editor, Walter Burns, who is sure Williams' conviction has more to do with winning the city's black vote than guilt, convinces his ace reporter to postpone his departure and exonerate Williams.

In Howard Hawks' film, Hildy is short for Hildegarde, who is both Walter's ace reporter and ex-wife. She arrives back in her paper's offices, also on the day before Williams' execution, to tell Walter she will marry insurance salesman Bruce Baldwin in Albany the next day. Except for one somewhat confusing indictment of capitalism's responsibility for gun proliferation, the movie is a wise-cracking battle of the sexes.

Guare has kept the relationship of Burns (Sills) and Johnson (Lyon) intact, changed Williams to Polish refugee Earl Holub (Kerr), changed the ethnicity of the murdered cop to German-American, and set the play in mid-1939, a day before the Nazis invade Poland. The play's targets now include law enforcement incompetence, official corruption, the press' myopic pack mentality, the justice system, the looming threat of totalitarianism, growing xenophobia, and more. It's too much to remain sublimated to the central "Comedy of Remarriage." We exit after two and a half hours as after a wedding with too many demanding guests, just wishing we could have spent more time with the bride and groom.

Meanwhile, the ongoing debates over gun violence, American intervention, and especially workplace equality for women, are hardly mentioned if they come up at all. Bizarrely, the only person who has problems with Hildy's advancement is a woman. Instead, Guare blends Hildy into the newsroom's frat-house camaraderie, where it isn't the woman – or African-American reporter – who are made to feel unwelcome, but the nerdy Benzinger (McGrath) and the woeful Mollie McGuire (Lind), who befriends Holub, but is dismissed as a whore. When the reporters have something to report, the pack mentality comes through as a Greek chorus rotating through their lines like a revolver. It's not only hard to follow, it blurs their individuality.

The good news is the acting at the top of the pyramid. Sills gives Burns his clearest identity yet. He and Ashley opt to have him truly concerned for Holub's life. This also gives him a heart we can root for when he tries to win back Hildy. We can buy that he is as concerned for her as he is for his ego and the paper's circulation. Unfortunately, that suffers somewhat when he is appears unaffected by Mollie's suicide. It sacrifices that fundamental trait of likeability for a throwaway laugh that didn't land after all.

For her part, Lyon makes Hildy fit into the male world while distinguishing her from it. When she arrives to show off her engagement ring and see how her colleagues are doing, she seems genuinely interested in them. She's a breeze that clears the room of the stale surface chatter and mutual taunting that passed for collegiality among the men.

Kerr makes the hapless Holub a sympathetic character. To get him into the press room, he escapes his cell with a gun stolen from the sheriff. It's the Kaufman " Hart side if a conflicted play that also wants to be Odetts. Mackay does excellent work finding Baldwin's center of gravity, while McGrath does what he can to flesh out the unnecessary Benzinger. Lind shines in her role as the unfortunate Mollie. Several brief appearances by Jonathan McMurtry as a lost priest and Steve Gunderson in another unnecessary role are highlights.

The physical production shows the Playhouse's commitment to serving the play. Robert Brill's exhibition-quality set includes a high, relief ceiling that catches the shadows from gallows in the courthouse courtyard below. Paul Tazewell's costumes are period perfect. David Lander's light plot overcomes the ceiling challenge, making it look easy. Music by Mark Bennet, hair and wigs by Charles LaPointe, and stage management under Charles Means are all first rate.

What the project seems to want is a tough editor equally atuned to storytelling and ticket sales. If only Walter Burns could pull a Purple Rose of Cairo and come down to spend a weekend with the playwright. He'd take a sharp blue pencil to those galleys, slash peripheral characters and conflicts, all the while shouting, "You've forgotten that they want to see me and Hildy!"

Guare has said as much himself. "I want our audience to be . . . watching these two go at each other," he stated in a program interview. "We want Walter to ensnare Hildy, the love of his life, and see how Hildy is going to escape." To make that clearer much of the rest could be cleared.

top of page

HIS GIRL FRIDAY

adapted by JOHN GUARE

from The Front Page by

BEN HECHT and CHARLES MacARTHUR

and COLUMBIA PICTURES'

motion picture His Girl Friday

directed by CHRISTOPHER ASHLEY

LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE

May 28-June 30, 2013

Opened 5/9, rev’d 6/22m

CAST Bill Christ, Evan D'Angeles, Steve Gunderson, Michael Hammond, William Hill, Chaz Shermil Hodges, Gerard Joseph, Patrick Kerr, Kevin Koppman-Gue, Behtany Anne Lind, Jenn Lyon, Donald Sage Mackay, George McDaniel, Matt McGrath, Jonathan McMurtry, Dale Morris, Victor Morris, Dion Mucciacito, Mary Beth Peil, James Saba, Mike Sears, Douglas Sills, Ronald Washington

PRODUCTION Robert Brill, set; Paul Tazewell, costumes; David Lander, lights; Mark Bennett, music/sound; Steve Rankin, fights; Charles LaPointe, hair/wigs; Eva Barnes, dialects; Gabriel Greene, dramaturg; Charles Means/Jennifer Kozumplik, stage management

George McDaniel, Gerard Joseph, Douglas Sills, Jenn Lyon and Ronald Washington

Photo | Kevin Berne

Bilingual 'Wichita'

A slow-to-ignite love affair between newly admitted nursing home residents launches playwright Lina Gallegos' Wild in Wi chita, a poignant comedy about end-of-life renewal. Consecutive two-week stagings of Spanish and English versions, both directed for L.A.'s Bilingual Foundation of the Arts by Denise Blasor, closed on June 2.

Seventy-year-old Carmela (Blasor) and 73-year-old Joaquin (Sal Lopez) are brought by their adult children to a Wichita, Kansas care facility from their homes in New York and Texas, respectively. The kids moved here years ago for their own families and careers. Now, seeing that their parents' health and spirits are starting to flag, they want to be able to check on them.

Carmela and Joaquin soon hear the comforting sound of each other's accent and begin sharing bilingual memories of music, food, and phrases. But the mother tongue only goes so far, and cultural distinctions between her Puerto Rican and his Mexican traditions soon fuel a comic dual of ethnic one-upmanship.

The biggest difference between them, however, is in their relationships with relationships. Never married, the former New York teacher has only her adopted son Raul (David Carreño) in her life. Joaquin, who successfully ran a hardware store in Fort Worth, remains a committed romantic despite four failed marriages, one of which produced daughter Lilian (Crissy Guerrero).

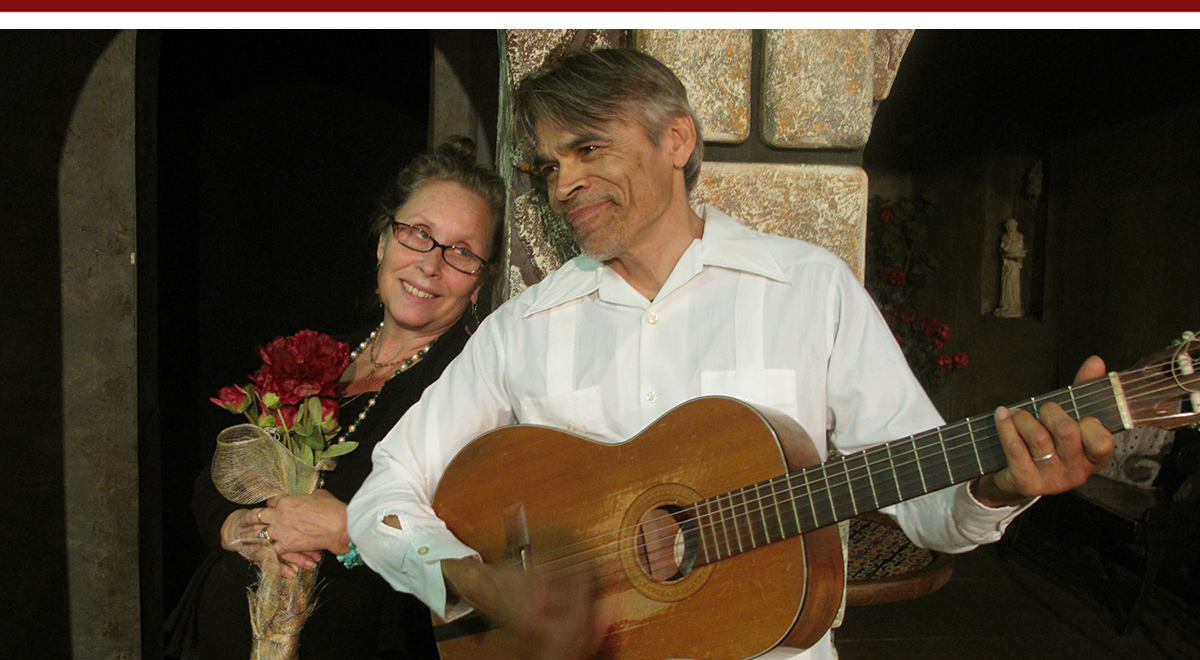

Given the opportunity, Joaquin is programmed to flirt, and despite Carmela's sharp-tongued rebukes, he straps on his guitar for a first act of serenading and seduction. It's a familiar dynamic for those who know Terrence McNally's Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, in which a self-protecting woman is increasingly suspicious of her suitor's insistence that they are destined for each other. Unlike the duo "in the Clair de Lune," who are facing middle age alone, the stakes are paradoxically higher and less important in the waning moonlight of Wichita's Septuagenarians.

Busy work schedules prevent regular visits by Lilian and Raul, but they do check in by phone. Once they get wind of their parents' romance, they meet over the phone to express concerns and cast aspersions.

Although in the English version we saw Blasor and Lopez are too young for their roles, it doesn't matter. His Joaquin has such charisma that his gradual wearing down of the prickly Carmela gives the production its greatest appeal. We see in Blasor's portrayal that it is a lifetime of hurt that has left her reluctant, even at this late stage, to take a chance. But, by the end of Act I they are stealing away to skinny dip and generally behaving like teenagers. An elopement is discussed and then, to end the act, tragedy strikes and the entire play veers into the unknown.

For Act II, Gallegos keeps the uncertainty alive with a clever misdirect, abetted by the Lilian's and Raul's decision to dress all in black. The younger characters have the stage to themselves for a scene in which they get to know each other. Subtle parallels between the older and younger generations emerge, including echoes of the cultural pride they inherited.

Unfortunately, Gallegos has effectively run out of story and the rest of the second act feels like it's been extended to stretch what should have been a 90-minute one act. Joaquin must go through another round of winning Carmela's affections. This time she holds her tongue, but only because she either refuses to speak or is in a mild state of catatonia. Thanks to Lopez' winning ways, the filler keeps its flavor.

For her part, Blasor allows Carmela to hit tones at the opposite ends of her demeanor: aged, bitter and prickly to begin with, but giddy with hopefulness when she lets herself go. Carreña is a solid son, and his scenes of suppressed flirtation with Guerrero's appealing Lilian hit their mark. In addition to her fine portrayal, Guerrero gets an opportunity to show off her singing, with a sublime "Besemé Mucho."

For BFA Blasor simultaneously directed a Spanish-language version, Locuras en Wichita, that began the run, and the English Wild in Wichita that finished it off. The en español actors were Margarita Lamas as Carmela, Miguel Santana as Joaquin, Jossara Jinaro as Lilian, and Carreño doubling up as Raul.

Jorge Alonso Luna's set is impressive as it fills the stage with three locations – the nursing home's gathering area as well as sections of Lilian's and Raul's homes. But future productions could easily get away with something as simple as a couch, chair and table, and the younger generation making their calls in isolated downspots. Companies should know this is a very producible play. It's first-rate material that L.A.'s theater community, especially the long-courted but rarely seduced Hispanic audience, are ready to fall in love with.

top of page

WILD IN WICHITA

by LINA GALLEGOS

directed by DENISE BLASOR

BILINGUAL FOUNDATION

OF THE ARTS

May 9-June 2, 2013

Opened 5/9, rev’d 6/1

CAST English (reviewed here) – Denise Blasor, David Carreño, Crissy Guerrero, Sal Lopez; Spanish – Carreño, Jossara Jinaro, Margarita Lamas, Miguel Santana

PRODUCTION Jorge Alonso Luna, set; Cecilia Garcia-Serrano, costumes; David Carreño, lights; Cecilia Garcia-Serrano, stage management