MAY 2014

Click title to jump to review

COME BACK, LITTLE SHEBA by William Inge | A Noise Within

A DELICATE BALANCE by Edward Albee | Odyssey Theatre

DIFFERENT WORDS FOR THE SAME THING by Kimber Lee | Kirk Douglas Theatre

PASSION PLAY by Sarah Ruhl | Chance Theater

PRAY TO BALL by Amir Abdullah | Skylight Theatre Company

TARTUFFE by Molière | South Coast Repertory

A classic case

William Inge’s curiously titled classic from the 1950s takes its name from the pointless calls of a frustrated woman. In her cries for a runaway dog we can hear a yearning for love and a time when her now-remote husband desired her. Come Back, Little Sheba (through May 17) is one of three currently running rep productions at A Noise Within in Pasadena.

Co-Founding Artistic Directors Geoff Elliott and Julia Rodriguez-Elliott direct company stalwart Deborah Strang as Lola Delaney and Elliott as her husband Doc in a beautiful production designed by Steven Gifford (set), Leah Piehl (costumes), Ken Booth (lights) and Doug Newell (sound).

The play is among several prominent mid-Century works of literature, film, and theater that took an honest, empathetic look at alcoholism. Inge based his work on his own battles, naming Lola after the wife of a sponsor in his own Alcoholics Anonymous group. Inge was happy to promote the mission of AA, then a 15-year-old organization, and its 12 Step Program, which had helped him stay sober while writing this, his second play, as a professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

Like Inge at that time, Doc is in recovery, regularly attending meetings and checking in with his sponsor, Ed Anderson (Mitchell Edmonds). He and Lola are also rebuilding from years of dwindling income as patients abandoned Doc's unreliable chiropractic practice. They now take in boarders.

Although Doc has successfully moved beyond the tug of the bottle, he is not free of the daily drive to escape the realities of his marriage. That has found fresh fantasy in their young lodger, Marie (Lila Fuller), a perky coed finishing her college studies. Lola's occasional attempts to attract Doc's eye are quickly doused by excuses to get to the office, retire early, read, and so on. He only comes alive when Marie is in the room, but clearly does not understand the dangers of a lust he hides under fatherly platitudes about her decency, concerns for her welfare, and dislike for her current boyfriend, the handsome young Turk (Miles Gaston Villanueva), whom she keeps handy for cuddling on the Delaneys' couch and lovemaking in the secrecy of her bedroom.

Marie is young enough to be innocent of her effect on the stunted middle-aged Doc, and Lola is so restricted by decades of housewifery that she is clueless, too. Doc himself is unaware of the depth and danger of his needs, even as he steals a snootful of her perfume off a scarf left on a handrail. His desires are all the more explosive for their complete denial, and when Doc catches sight of Turk slipping out of Marie's room one morning, his months of disciplined sobriety slip out after him. Doc grabs the dusty whiskey bottle that he was able to ignore and is off for a backsliding bender. When he does not return, and Lola sees the bottle is missing, she calls Ed and they ready themselves for him to stumble back home.

As she does with each assignment, Ms. Strang slips completely into her role, finding Lola's ache and then showing how she hides her rejection in her routines. Deprived of real love, she also uses Marie for escape, eavesdropping on her trysts as she might peek at gossip magazines. But hers is an honest rooting interest in the student's affairs.

Fuller is able to ride the balance between consciously using her appeal to manipulatie Turk and being unaware of its effect on the older Doc. Turk doesn't know that she will soon return to her hometown boyfriend Bruce (Paul Culos), who visits just as Doc is losing his grip. Company members Edmonds and the always appealing Jill Hill, as the neighbor, Mrs. Coffman, add rich resources to their characters, while Jack Elliott, James Ferrero, and John Klopping satisfactorily fill the minor roles.

How an actor scales Doc's sudden, monumental arc will make or break a production of Come Back, Little Sheba. Elliott starts out with the right reserve and fires up sufficent explosives. What he doesn't give us is Doc's paradoxical control of the uncontrollable seething within him. This is as challenging an assignment as anything in theater. It's a wordless, intentionally disguised behavior that requires virtually telepathic, osmotic transference to the audience. Without that, when the fuse is finally lit, and the collateral damage is done, it can seem an over-reaction for someone merely concerned with a young woman's morals.

top of page

COME BACK,

LITTLE SHEBA

by WILLIAM INGE

directed by GEOFF ELLIOTT

and JULIA RODRIGUEZ-ELLIOTT

A NOISE WITHIN

Mar 29 - May 17, 2014

(Opened 3/29, Rev’d 5/4e)

CAST Paul Culos, Mitchell Edmonds, Geoff Elliott, Jack Elliott, James Ferrero, Lili Fuller, John Klopping, Deborah Strang, Miles Gaston Villanueva

PRODUCTION Stephen Gifford, set; Leah Piehl, costumes; Ken Booth, lights; Doug Newell, sound; Caity Hawksley, hair/wigs/makeup; Ken Merckx, choreography; Michelle L. Gutierrez/Emily Lehrer, stage management

Lili Fuller and Deborah Strang

Craig Schwartz

The tear

Our acquired routines, rituals, and religions may just be security blankets that keep us protected from seeing our lives like fragile bubbles floating through an infinite abyss. If our blanket tears and we glimpse the void, we might look for understanding friends to provide a sanctuary where we can rebind our blinders.

Such is the case in Edward Albee's 1966 Pulitzer Prize-winning A Delicate Balance, now receiving a well-cast, well-conceived remounting (through June 15) under Robin Larsen's direction at the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble.

It begins like any weekend in the comfortable surroundings of Agnes and Tobias' two-story suburban home. Agnes and Tobias are engaging in the routine head butting that has kept their marriage active and intact. One point of contention concerns Agnes' sister Claire, an aging free spirit who slips on and off the wagon as easily as a teamster. She is back off this Friday evening, which rankles her older sibling but not her brother-in-law, who appears to appreciate her uncorked frankness.

Then Harry and Edna unexpectedly appear at their door. After the required pleasantries of the "upper-upper middle-class," as Albee describes them, they explain the intrusion. They were sitting at home, says Harry, and it "was all very quiet; we were all alone, and then . . . nothing happened, but. . . " "We got frightened," explains Edna. "We were very scared," Harry adds, "It was like being lost, very young again, with the dark, and lost. There was no thing to be frightened of. . . . We couldn't stay there. So we came here. You're our very best friends."

Agnes (Susan Sullivan) and Tobias (David Selby) are understanding and welcoming, but surprised when Harry (Mark Costello) and Edna (Lily Knight) head off to hole up in the spare room 'til they calm down. The house was already crowded with one big personality, Claire (O-Lan Jones), and their 36-year-old daughter Julia (Deborah Puette) is bringing her self-preoccupation after the collapse of her fourth marriage. She expects to indefinitely reclaim her old bedroom, now the spare room.

Claire's challenges and Julia's mistakes will consume the family members until Sunday morning, when Tobias asks Harry what would happen if roles were reversed. Is the friendship equally balanced? Would Harry and Edna be as hospitable? Harry admits he would not.

This is a highly improbable response given the accoommodations Agnes and Tobias made, and provided, especially given the years of friendship. But, Albee must know people who would take decades to reveal such a fundamental lack of character. The incomprehensible lack of equity, however, succeeds in tear Tobias' security blanket of beliefs, the foundation of which was friendship and loyalty. As Harry's shallowness sinks in, Tobias' faith in humanity begins to reverberate wildly and like a building hit with sub-atomic vibrations, he implodes in a heap of tears.

Albee's character descriptions put Agnes in her late 50s and Tobias a couple years older. That would suggest they are not yet retired, which makes the absence of any reference to careers or professions telling. Selby and Sullivan are a decade older, suggesting they are retired rather than merely detached from their work. Either way, the focus is on the relationships and Albee's assertion, as he writes in the 1996 reprint, that "The play concerns . . . the rigidity and ultimate paralysis which afflicts those who settle in too easily, waking up one day to discover that all the choices they have avoided no longer give them any freedom of choice."

Selby is at his best here as the detached patrician overseer, retreating into reading material whenever possible and hoping the sisters can keep their combat between themselves. However, after Harry's act of betrayal throws him into that bottomless void, Selby can't render the depth and breadth of Tobias' plummet. There's no lack of effort on his part, but the tirade doesn't rattle with systemic terror as it must, merely sound and fury.

Jones and Puette give their characters real clarity and individuality. Jones' Claire is a feast of supplemental gestures and inflections that help her goad conversation into confrontation, often from the sidelines. They are flashy yet appropriate choices. By exposing others' hestitance to be forthcoming, she hopes to avoid eposing her own lack of substance. Puette correctly makes Julia a shrill, self-absorbed character, hard to sympathize with, which fits Albee's view that, as he said in a 2003 "Theater Talk" interview, "Anybody should have an awareness of the finality of life as early as possible. That way you don't waste your time." Julia is wasting a lot of time.

Costello and Knight are excellent. Costello's Harry remains genial and placid throughout. His mask of complacency hardly shifts at all despite the turmoil. Knight's Edna is, as the text indicates, more affected by the event. But she channels her terror into a stern sense of righteousness and entitlement.

Though Tobias' epiphanous upheaval gives the play its climactic fulcrum, the character of Agnes provides plenty of opportunities for Sullivan to show why any production lucky enough to get her is worth getting to see. She helps Larsen's well-modulated staging move by briskly, belying its near three-hour length.

Scenic designer Tom Buderwitz and lighting designer Leigh Allen have given Larsen a great space in which to create her world. With just the right elements, they give the intimate stage a sense of a world of established comfort. Dianne K. Graebner's costumes add class and distinction to the characters. Christopher Moscatiello provides sound design, and Alexx Zachary is stage manager.

top of page

A DELICATE BALANCE

by EDWARD ALBEE

directed by ROBIN LARSEN

ODYSSEY THEATRE ENSEMBLE

May 3-June 15, 2014

(Opened 5/3, Rev’d 5/4m)

CAST Mark Costello, O-Lan Jones, Lily Knight, Deborah Puette, David Selby, Susan Sullivan

PRODUCTION Tom Buderwitz, set; Dianne K. Graebner, costumes; Leigh Allen, lights; Christopher Moscatiello, sound; Alexx Zachary, stage management

HISTORY A Delicate Balance premiered on Broadway September 12, 1966 with Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn in the leads, and a young Marian Seldes as Julia. Alan Schneider directed the production at the Martin Beck Theatre.

David Selby and Susan Sullivan

Enci Box

Back and forth

As designer Geoff Korf's final light cue trains a fading spotlight on the narrator of Kimber Lee's different words for the same thing, we at last understand the various threads of this hypnotic new work. As an origami artist might, in a final fold, reveal the exotic bird hiding in the creases and flaps, we can see what Ms. Lee saw all along. And, it is beautiful and haunting.

Under Neel Keller's empathetic, restrained direction, this Kirk Douglas Theatre world premiere is exciting in its non-linear, time-fragmenting approach that seems to move back and forth between time and place, without insisting on detail. To appreciate the work, and protect the enigma for those who will see it, we look not at the climactic reveal, but unfold the story back to the flat, blank sheet where the single-act, 110-minute play begins.

Our narrator is alone onstage among a dispersed collection of rolling set pieces. She is using a scene from the final moments of Titanic to explain her experience: Kathy Bates' character exhorts the passengers in her lifeboat to return and save people, despite the risk to their own lives. The unidentified narrator, her recollection, and its importance all seem to float onstage, as a telephone is ringing somewhere. The promise of illumination is represented by many unmatching lamps suspended throughout the expanse of the Douglas stage, which Sarah Krainin has paneled in light wood. The disparate fixtures will be made uniform by the time we watch Korf's final cue, providing another sign that we have found a sameness in that thing the author is after.

We learn that our guide is Alice (Jackie Chung). Like Ms. Lee, she is Korean born, and lived in Nampa, Idaho (where the play is set), before moving East for her career – Alice to Chicago, Ms. Lee to Brooklyn. In Nampa, we begin with Marta (Alyson Reed) and Henry (Sam Anderson) selecting a burial casket for a recently departed loved one. This is a time of reflection, rededication, or change for all the characters we meet: Oren (Stephen Ellis), who is helping them at the mortuary, has dropped his singing role at church and will pursue its shy organist Donna Ruth (Rebecca Larsen), who will reluctantly emerge from her shell, too; donut shop manager Mike (Malcolm Madera) will also find the resolve to connect with a love interest; restaurant owner Angel (Hector Atreyu Ruiz) needs to improve his relationship with in-laws while his daughter Sylvie (Savannah Lathem) and his employee Frankie (Erick Lopez) want to bring their young romance into the open, despite public discouragement from the town busybody, Dottie (Monica Horan).

The person facing the biggest life change is Maddy (Devin Kelley), who observes the others with mild frustration, moving between vignettes to listen in but never speak until she visits Father Joe (José Zuniga). His participation in her odyssey is new and potentially disturbing for him, but the experience appears to be helping him relate to his parishioners as well as those from the city's other church.

How these people all connect remains a complete mystery for much of the first half, as we get to know each of them and their stories in isolation. They eventually merge in a fantastic – perhaps imagined – unifying scene.

The entire cast is outstanding and is in sync with the play's overall tone. Under Lee and Keller's vision they have created a chamber piece that plays its themes lightly and refrains from underscoring its points. Like a musical composition, it strikes a final chord in a signature key, minor in tone but with beautiful resolution.

In addition to the work of Krainin and Korf, Candice Cain provides individuality in her costume design, while Paul James Predergast creates a wonderful mix of music and sound design.

That the title of different words for the same thing is written, as are all Ms. Lee's plays, without capitalization reminds us that Asian sentences have no initial caps. And, while she could just as logically have written the title in all capitals, that wouldn't fit with the modest nature the work, which is what allows it to make such a big impression.

top of page

DIFFERENT WORDS

FOR THE SAME THING

by KIMBER LEE

directed by NEEL KELLER

KIRK DOUGLAS THEATRE

May 4-June 1, 2014

(Opened 5/11, Rev’d 5/18e)

CAST Sam Anderson, Jackie Chung, Stephen Ellis, Monica Horan, Devin Kelley, Rebecca Larsen, Savannah Lathem, Erick Lopez, Malcolm Madera, Alyson Reed, Hector Atreyu Ruiz, José Zuniga

PRODUCTION Sarah Krainin, set; Candice Cain, costumes; Geoff Korf, lights; Paul James Prendergast, music/sound; Kirsten Parker, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

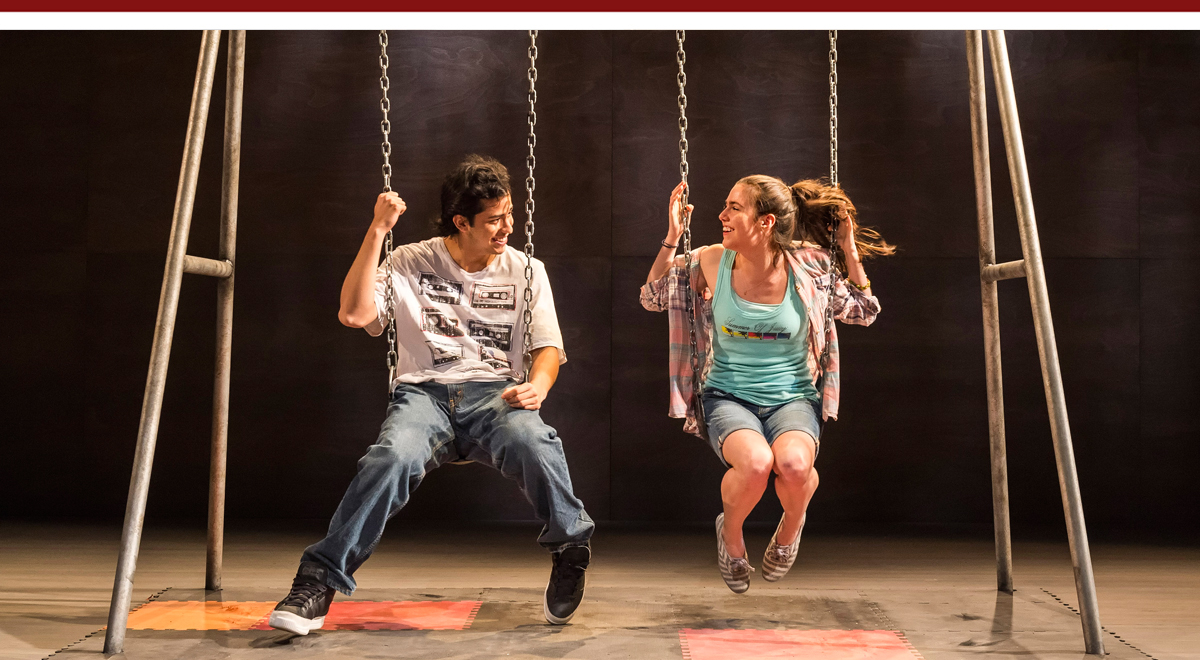

Erick Lopez and Savannah Lathem

Craig Schwartz

Sermon in the mount

When Sarah Ruhl was studying with Paula Vogel at Brown University, and adjusting her career path from poet to playwright, she started Passion Play. It took its title from the Christian tradition that annually brings theater to religion, and vice versa, in dramatic interpretations that tell of Jesus' final days or in some versions the full Bible story of man from Genesis to Revelations. She began it at age 21, finished it at 31, and now nearly a decade later it makes its Orange County premiere at Chance Theater in Anaheim Hills.

About 800 years before Andrew Lloyd Webber made Jesus a Broadway baby, communities employed theater to mount God's word in grass-roots productions, often performed in the weeks around Easter. Ruhl was interested in how lay people to theater and the church were affected by their temporary elevation to local celebrities and figures from The Bible. As annual events, there was also the challenge of keeping one's role, or risking losing it to a pretender to the part.

The playwright takes us to separate productions in England, Germany, and America spanning 400 years. Each of these is an hour-long act, which is probably more time than is required, but credit director Trevor Bishop's 11-member cast with keeping this second production in Chance's second home engaging throughout. Ruhl's poetic strengths are evident. Her writing lifts these villagers and country folk into literary characters, and their stories verge on mythic. She does not create linear narrative but sweeps her way through history with a constant sense of inquiry into how faith imposes on ordinary people in and out of the pageant.

The rehearsals for the English mounting represent one of the final stagings in 1575, the year Elizabeth I banned all productions in her move to end the power of the Catholic Church. A frightening Queen Elizabeth (Karen Webster) appear, the manifestation of the real treat she represents. On Fred Kinney's large, deceptively simple set, the earnest rehearsals progress as we meet the craftsmen and laborers who will soon transform into Biblical figures.

Next its Bavaria in 1934, where Oberamergau became the epicenter of the process. Secular power is now represented by Chancelor Hitler, who is a big supporter of the Passion Play, as it seems to put Jews in a bad light, and (Webster again) he makes a famous appearance in the audience that same year as his Nazi-led government hosted the Olympics. Bishop, Kinney and Lighting Designer Brandon Baruch reveal more wonders in their production, as cast members help build the railroad that will lead to the camps.

For the third act we move to America, and the town of Spearfish, South Dakota, beginning in 1969 as the Vietnam War is raging. One actor answers the call of duty, joining up and losing his role in the re-enactment. This creaties a rift with those who stayed behind. We move ahead to 1984 (coincidentally L.A.'s Olympic year), when President Reagan (Webster) attends as part of his re-election campaigning.

In each act, Ben Moroski plays the charismatic Messiah, called simply John the Fisherman, and lets us feel both the pride and pressure associated with the part. Casey Long is his offstage friend and onstage rival, Pontius the Fishgutter, until the third act when he is off to Vietnam. Camryn Zelinger and Katelyn Schiller provide rich portraits of the near-interchangeable Mary 1 and Mary 2, whose offstage lives are greately impacted by their roles as Magdalene and the Virgin Mother. Other noteworthy performers are Alex Bueno as an sympathetic Village Idiot who will also be known as Violet, but her old disability will target her for the railway to the camps. Karen O'Hanlon gets the most variety, as a Monk in England, a British reporter in Germany, and a small but distinct appearance in the South Dakota section. Robert Foran and Jackson Tobiska as two directors both make strong showings, with Tobiska an appreciably well-rounded Nazi officer.

Credit Bishop, and the design team, which also includes costumer Sarah Ryung Clement, sound designer Jeff Potunas, and puppet makers Christopher Scott Murillo and Brittany Blouch with creating a dramatic environment in the vast rectangular room. It is a great achievement for the company to take on the demanding, wide-ranging world of this play and give it such coherence and appeal.

top of page

PASSION PLAY

by SARAH RUHL

directed by TREVOR BISHOP

CHANCE THEATER

April 25-May 25, 2014

(Opened 5/2, Rev’d 5/17e)

CAST Alex Bueno, Andrew Eiden, Robert Foran, Lee Kociela, Casey Long, Ben Moroski, Karen O'Hanlon, Katelyn Schiller, and Camryn Zelinger

PRODUCTION Fred Kinney, set; Sara Ryung Clement, costumes; Brandon Baruch, lights; Jeff Polunas, sound; Christopher Scott Murillo, puppets; Kathryn Davies/Jamie A. Tucker, stage management

Katelyn Schiller and Camryn Zelinger

Thamer Bajjali

Pray to play

Does a dramatist with beliefs need to watch how much of his heart is in his art? Pray to Ball is an extremely likeable first play by Amir Abdullah. It is also a more important play than most. Its subjects are contemporary and ageless. But watching the first act of its well-realized world premiere, directed by Bill Mendieta at the Skylight Theatre Company, one wonders if he is wrestling with these issues or tackling them?

Perhaps that is what separates playwriting from proselytizing. If there is inevitability below the surface, and characters seem to lose free will, a work's center of gravity moves out of art and into doctrine. Though this threatens to be the road we're on during the first act, as the play ends we feel the protagonist will make his choice free of the playwright's wishes.

These concerns are most evident in a play that addresses the benefits of a particular religious belief. Certainly Islam deserves this positive presentation, and anyone fortunate enough to enjoy this production will be better for it. But, there is another hugely topical element for young people who are engaging in high-profile high-profitability sports, especially at a time when athletes at one university have been allowed to unionize as income-producers.

Pray to Ball (the title pokes fun at the divine supremacy sports too often commands) follows the college career of an incoming star basketball player at the University of Miami. In three locales, beautifully created by set and lighting designer Jeff McLaughlin, we move easily between the University of Miami dorm room shared by Hakeem Johnson (Y'lan Noel) and Lu Le Roux (Abdullah), the basketball court complete with hoops, and the office of an Islamic outreach center.

Johnson arrives for his first year at school, rooming with his best friend Le Roux, who is back for a second year after a team-leading debut season with the Hurricanes. Among the welcome pamphlets shoved under the dorm door is one from the Islamic center. Unfortunately, before he can enjoy the bounty of treats available to the big men on campus, Johnson is suddenly called home, where his mother is dying. Back at school, and grieving, his heart isn't into drunken excess when Le Roux returns from a party with beautiful coeds – Nika (Lindsey Beeman) and her very drunk friend (Ulka Simone Mohanty). When Le Roux and Nika leave for her room, the friend collapses into deep sleep.

The devastating loss of his mother adds to an increasing wariness about basketball's limitations. And the exploitation of both the university system and the media – represented by a national TV analyst played by Brice Harris – compels Johnson to check out the Muslim center, overseen by Bilal (Rickie Peete), a reformed user and petty criminal who served time. Bilal is a no-pressure representative, helping explain the benefits to Johnson while standing up to Le Roux's eventual hostility for what he views as diverting his friend from his destiny.

On his second visit he recognizes a center worker as Nika's belligerent friend, Tamana. Tamana and Johnson will be drawn together, which is complicated by Muslim prohibitions against physical contact.

Despite the real-world dialogue and strong acting under Mendieta's direction, the first act of the play has the dutiful inevitability of an educational film. A more experienced actor might give Tamana greater depth of conflict, guilt, desire, etc., which could help that first act. But the end, however, despite the predictability, Johnson seems able to choose his own course.

Much credit goes to Noel, a recent transplant from Georgia, who grounds the play. Every conversation and situation feels real, even as the overarching context feels manipulated in the early going. The entire cast and design team, however, have done great work. It's a triumph for Abdullah, who clearly will have more to say and that will be good for theater and greater understanding.

top of page

PRAY TO BALL

by AMIR ABDULLAH

directed by BILL MENDIETA

SKYLIGHT THEATRE COMPANY

May 4-June 1, 2014

(Opened 4/26, Rev’d 5/18m)

CAST Amir Abdullah, Lindsey Beeman, Brice Harris, Ulka Simone Mohanty, Y'Lan Noel, Rickie Peete

PRODUCTION Jeff McLaughlin, set/lights; Kelly Bailey, costumes; Christopher Moscatiello, lights; Hana Kim, projections; Spencer Lee, video; Micaal Stevens, basketball choreographer; Colin Grossman, stage management

HISTORY Developed through Skylight Theatre Company's INKubator program; Produced by Gary Grossman, Tony Abatemarco, Adam Rotenburg World Premiere

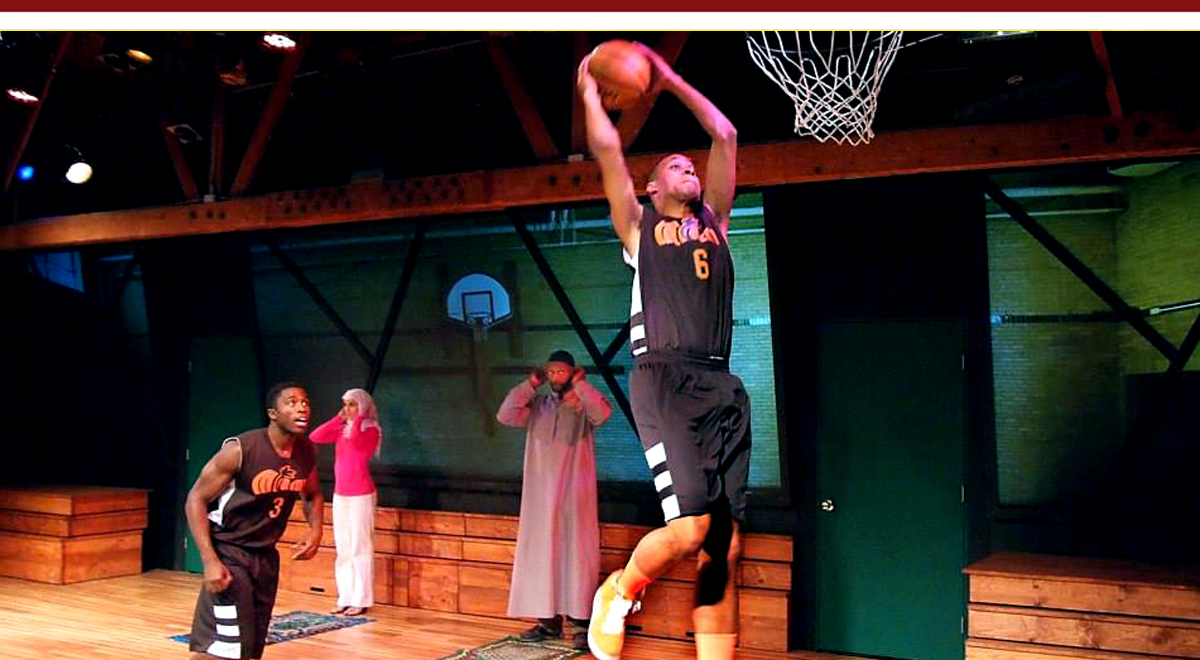

Rickie Peete, Ulka Simone Mohanty, Y'Lan Noel and Amir Abdullah

Ed Krieger

Sacred art

There are visual and performance achievements in Dominque Serrand's current staging of Molière's Tartuffe, at South Coast Repertory through June 8, that take stagecraft to the level of religious iconography and confirm that theater is a secular sanctuary in which to explore human nature, both the secular and devout.

The production, using David Ball's 1998 adaptation, ends SCR's 50th Season at SCR with the play that, in 1964, launched it as a homeless band of college graduates touring venues in a station wagon. Now a national institution under its second generation of leadership, it hands Serrand the keys for this landmark slot. He was a driving force behind Theatre de la Jeune Lune, founded in Paris in 1978 before moving to Minneapolis in 1985 and dissolving in 2008 to become The Moving Company, a homeless touring troupe whose actors and designers form the nucleus of this salute to SCR's institutional longevity and their own risk-taking independence. It is a co-production that will resurface at Berkeley Repertory Theatre in the fall.

That first scrappy touring production a half-century ago came during the 300th anniversary of Molière's play. Written as a warning for the pious of Paris to be en garde against religious charlatans, it so rankled members of high society and Church hierarchy that King Louis XIV, a fan of Molière and the play, yielded to their outrageous outrage and shuttered the production. Anyone caught attending, performing in, or even reading it risked excommunication. As Molière observed in a letter to Louis, "The originals have had the copy suppressed, no matter how innocent nor how true the likeness." Public performances resumed five years later, after the authority of the church, largely through oversteps like this one, had been weakened.

Without pre-show music, audiences wait for the show to begin before a satiny black drape bearing a projection of the play's title. Once houselights fade, a voiceover reads an excerpt from Molière's letter to the king, in which he condemns himself as "a devil dressed in flesh and clothed like a man, a freethinker, impious, worthy of exemplary execution." The self-indictment is unconvincing and doesn't stick. Perhaps Molière instead is being "hypocritical" to cast aspersions on his detractors.

The curtain rises to reveal the great entry hall in the home of Orgon (Luverne Seifert), a wealthy, God-fearing Parisian who is under the spell of a deceitful recent arrival in the city. Tartuffe (Stephen Epp) has beguiled both Orgon and his mother, Madame Pernelle (Michael Manuel). Seeing through the guise are wife Elmire (Cate Scott Campbell), son Damis (Brian Hostenske), daughter Mariane (Lenne Klingaman), brother-in-law Cleante (Gregory Linington), and Dorine the maid (Suzanne Warmanen). They appeal to Orgon's reason, but his faith has overridden it.

To get closer to Tartuffe and defy his own family, Orgon transfers his possessions to him. He commands Mariane to drop her engagement to Valere (Christopher Carley), and make this holy man his son-in-law. The greedy imposter goes too far when he attempts to seduce the beautiful Elmire, who convinces Orgon to eavesdrop on a tryst. But Orgon has come to his senses too late. Tartuffe orders the family out and calls upon the King to have him evicted. But Molière helps his case by portraying the King in the play as wise and kind, and his emissary has been ordered to arrest Tartuffe instead, on charges he was out to destroy his hoodwinked host.

Although it is written that Molière's characters end in rejoicing at this comeuppance, and this has the play maintain its comedy status, Serrand and Ball, another veteran Minneapolis collaborator, add an ominous twist. As he is led off, Tartuffe brandishes the frightening grin of enduring evil: the predator will keep returning so long as the faithful seek facilitators. A terrified Orgon immediately orders his home barricaded from inside.

The cast is superior. As the production's tentpoles, Seifert and Epp stand strong and in contrast. Epp is a reptilian shape-shifter, oozing his way into the family tree like the snake in the garden, an Edenic reference echoed by the occasional appearance of an apple. Seifert is never comic, but solidly self-righteous and authoritarian until he crumbles in the light of his error. Campbell is dutiful and restrained throughout, yet susceptible to Tartuffe's advances even as she undoes him. Manuel's Madame Pernelle is harshly one note, while Klingaman moves Mariane from comic lovesickness in the early stages to maturity as she understands the gravity of their situation. She and Carley, as her affianced Valere, are arch and hysterically over the top in their big encounter. It is one of several stylistic flourishes, judiciously employed, that show the acting company's range and control.

The players are part of the production's unified vision. Thomas Buderwitz, working as co-designer with Serrand from the director's original scenic concept, makes the single-set hall both grand and austere, its high gray-blue walls create a neutral backdrop against which the actors and set pieces compose magnificent stage pictures with the visual richness of Flemish painting. (Watch for the scene in which Orgon sits with his back to the audience.) The three walls rise behind the false proscenium into an upper story where tall windows can admit heaven's shafts. Alcoves and colonnades are present to conceal Tartuffe and his slippery assistants (Nathan Keepers and Nick Slimmer). Furniture and props are whisked on and off stage by an ensemble completely in tune with the mood of the enterprise. Becca Lustgarten, James MacEwan, Callie Prendiville and Slimmer all move as if in fear of losing their jobs.

Costume designer Sonya Berlovitz dresses everyone in black, white, and gray except Elmire and Marianne, who float among the others like flowers in a font, and Valere, wrapped in a wonderfully preposterous rose pattern better suited to mid-century bathroom wallpaper. But it is Marcus Dillard's lights that paint the production, often in dramatic sidelight, and move it out of the darkness of the opening night scene to the near-glare of the final awakening. With Corinne Carillo's sound design adding tension along the way, we begin under the secure shroud of belief in God's protection, and aware we are on our own and vulnerable. As the bolt locks Orgon's front door, we see that llumination comes at a price.

top of page

TARTUFFE

by MOLIERE

adapted by DAVID BALL

directed by DOMINIQUE SERRAND

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

May 9-June 8, 2014

(Opened 5/16, Rev’d 5/17m)

CAST Cate Scott Campbell, Christopher Carley, Steven Epp, Brian Hostenske, Nathan Keepers, Lenne Klingaman, Gregory Linington, Michael Manuel, Luverne Seifert, Suzanne Warmanen

PRODUCTION Dominique Serrand/Thomas Buderwitz, set; Sonya Berlovitz, costumes; Marcus Dilliard, lights; Corinne Carrillo, sound; Kathryn Davies/Jamie A. Tucker, stage management