NOVEMBER 2007

Click title to jump to review

ATLANTA by Adrian Pasdar and Marcus Hummon | Geffen Playhouse

ATTEMPTS ON HER LIFE by Steven Epp and Dominque Serrand from Marivaux's 'La Fausse Suivante' | Unknown Theatre / Evidence Room

CRY-BABY by Mark O'Donnell & Thomas Meehan, David Javerbaum & Adam Schlesinger | La Jolla Playhouse

DAWN'S LIGHT: THE JOURNEY OF GORDAN HIRABAYASHI by Jeanne Sakata | East West Players

DEAR BRUTUS by J.M. Barrie | A Noise Within

HANK WILLIAMS: LOST HIGHWAY by Randall Mylar and Mark Harelik | Laguna Playhouse

RAY CHARLES LIVE! by Suzan-Lori Parks | Pasadena Playhouse

TONIGHT AT 8:30 / 1 by Noel Coward | Antaeus Theatre Company

TONIGHT AT 8:30 / 3 by Noel Coward | Antaeus Theatre Company

The acting of the apostles

In 1985, Peter Barnes’ Red Noses suggested that the acts of a loose confederacy of 14th Century clowns could uplift audiences besieged by the Black Plague. The play was a testament to the transcendence of theater, many of whose practitioners were already battling our contemporary plague. Similarly, the fictional band of slave-actors at the heart of Atlanta, the Musical, now through January 6 at the Geffen Playhouse, provide insight into the disease of racism, while offering both escape and redemption for those within, as well as watching, the play.

Appropriately, Atlanta’s Civil War story, which combines Shakespeare, scripture and American music, premiered two years ago at Nashville’s Actors Bridge, a theater inside a chapel in the country music capital. It is the creation of co-librettists Adrian Pasdar and composer-lyricist Marcus Hummon. Following its modest debut, the script caught the interest of the Geffen Playhouse leadership, who worked with the writers to develop it for the production that opened November 28, co-directed by Pasdar and Geffen Artistic Director Randall Arney.

According to Hummon, a Nashville-based songwriter with co-writing credits for Rascal Flatts’ 2005 Grammy Award-winning "Bless the Broken Road" and hits by Wynonna, the Dixie Chicks, Tim McGraw and others, Pasdar had the original idea of a Union soldier finding love letters on the body of the Confederate soldier he kills. To this Hummon added the story of slaves groomed as a Shakespeare troupe by a Confederate Colonel whose troops are in the path of General Sherman’s march through Georgia.

While the various story lines prove too much for the play to satisfactorily explore, and Hummon’s music, while beautiful, does not thrill or fully probe the issues raised, there is much to commend this work and reason to hope that such a beautiful production, with consummate performance throughout, will guide the authors to filter the essential strengths from the elements clouding the view.

Currently, there seem to be two roads into this Atlanta: on its surface (the plots of soldiers and slaves) and in allegory that swirl in the air around it. Wisely, the co-directors have devised a physical production that underscores the allegorical, employing a talented design team led by scenic artist John Arnone. Through this lens the show nearly rises above its plot contrivances. Arnone’s set is its own act of reconciliation, at once outdoor theater and battlefield encampment it establishes an environment in which to explore dramas real and imagined. Behind the stage within the stage, three schooner-size sails of tent- canvas are held in the dead limbs of blackened trees, and serve as projection screens for period images and original video. Debra McGuire’s costumes also bridge the gap between representation and realism.

This duality extends to the performances of the eight-person company, who manage to deliver Shakespeare passages as well as original dialogue. Paul (Ken Barnett) is a Union soldier separated from his unit who runs into, then runs through, Confederate private Andrew Watkins (Quinn VanAntwerp), in the woods of north Georgia. It dawns on Paul as he stares at his victim that by appropriating Andrew's costume, he could slip through the tightening circle of rebels. It is the first invocation of acting as salvation and, if one pursues it, some biblical allusions by way of a converted Paul and martyred Andrew (note that Andrew dies upon the X-shaped 'Southern Cross' of a Confederate flag embedded in the stage floor).

In Andrew’s tunic, Paul discovers the correspondence from his lover, whose name is also Atlanta. As he reads, we hear (in a voiceover that hints at her true identity) Atlanta assure her faithfulness – to Andrew and their secret. Paul is soon apprehended by Confederate Lieutenant Virgil (Travis Johns) and taken into the inner circle of Colonel Medraut’s Confederate camp. Medraut (John Fleck) has created a strange bubble of culture to float above the atrocities. It contains a surviving trio of slaves trained and named in Shakespeare: Hamlet (Leonard Roberts), Puck (Moe Daniels) and Cleopatra (Merle Dandridge). A fourth, presumably a slave, named Bottom, has been killed. Paul, now calling himself Andrew, is allowed to fill in that part of the company within the company.

In Fleck, the directors have cast an idiosyncratic actor with a dossier of quirky comic creations. The choice works. Not only does Fleck prove himself free from reliance on schtick, he allows just the glimmer needed to promote the irony that the Colonel, the only major character not living under an assumed name, is missing his humanity and therefore the most like a fictional character. After the impostor private becomes an actor, he proceeds to playwriting. He then applies that skill to corresponding, as Andrew, with Atlanta.

Now Hummon and Pasdar have the freedom to move the story in pursuit of their (too-numerous) interests: back and forth between their dialogue and Shakespeare text: the Andrew-Atlanta story, the Medraut-slave relationships, and a complex matrix of affections between the slaves. At the same time, there is commentary on war, love and tyranny from the Collected Works, which in Medraut’s references to The Book, take on the importance of Bible passages: Romeo and Juliet for mismatched lovers, Lear for the shell-shocked Colonel; sonnets for Andrew and Atlanta.

Hummon, who enjoys turning Shakespeare soliloquies and sonnets into song, as he did with Hamlet’s famous speech in his 2005 boxing opera, Surrender Road, really employs the technique here. Unfortunately, these efforts are neither fish nor fowl, failing as either engaging music or well delivered Shakespeare. They might have more impact just delivered over underscoring from the great band (especially the sweet violin of Karen Briggs). Despite his hit-making credentials, Hummon does not appear to have built Atlanta’s score on popular music hooks. He has employed subtler vernaculars and orchestrated them simply, for piano, percussion and strings (from violin and cello to guitar, dobro, mandolin and banjo). The rich on stage band -- sequestered upstage under the direction of keyboardist Kevin Toney -- fittingly renders the music as something found around American front porches and campfire pits, rather than Broadway pits.

While Atlanta works its big-canvas ideas of art and life, and often succeeds in its microcosmic two-actor scenes, it loses the middle ground of plot movement. Its strength is as a dreamy vision of an America recognizing its soul and reconciling its past. Beyond that, it is about being authentic, and the irony that art can sometime reflect enough understanding to change people. Although it still contains plenty of undercutting paradox: the man with greatest access to culture remains the most corrupted. Nevertheless, despite all this, Arney and his army have made Atlanta a worthy salute to the power of art – specifically theater – as sanctuary and source of education, reconciliation and exploration. One hopes the conflict between its two states can be worked out down the road.

top of page

ATLANTA, THE MUSICAL

by MARCUS HUMMON

and ADRIAN PASDAR

music and lyrics byMARCUS HUMMON

directed by RANDALL ARNEY

and ADRIAN PASDAR

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

November 20–January 6, 2007

(Opened, rev’d. 11/28)

CAST Ken Barnett, Merle Dandridge, Moe Daniels, John Fleck, Travis Johns, JoNell Kennedy, Leonard Roberts • Chorus (u/s) – Keith Arthur Bolden, Michael G. Hawkins, Victoria Platt, Tasha Taylor, Quinn VanAntwerp

MUSICIANS Andrew Rollins, guitars, keyboards, vocals; Kevin Toney, keyboards; Chris Ross, percussion; Karen Briggs, violin; Ryan Crossley, cello and bass

PRODUCTION John Arnone, set; Debra McGuire, costumes; Daniel Ionazzi, lights; Brian Hsieh, sound; Kevin Toney, musical direction; Kay Cole, musical staging; Amy Levinson Millan, dramaturg; Jill Gold, stage management

HISTORY Funding support–Sheila Grether-Marion and Mark Marion, NEA’s "American Masterpieces: Three Centuries of Artistic Genius"

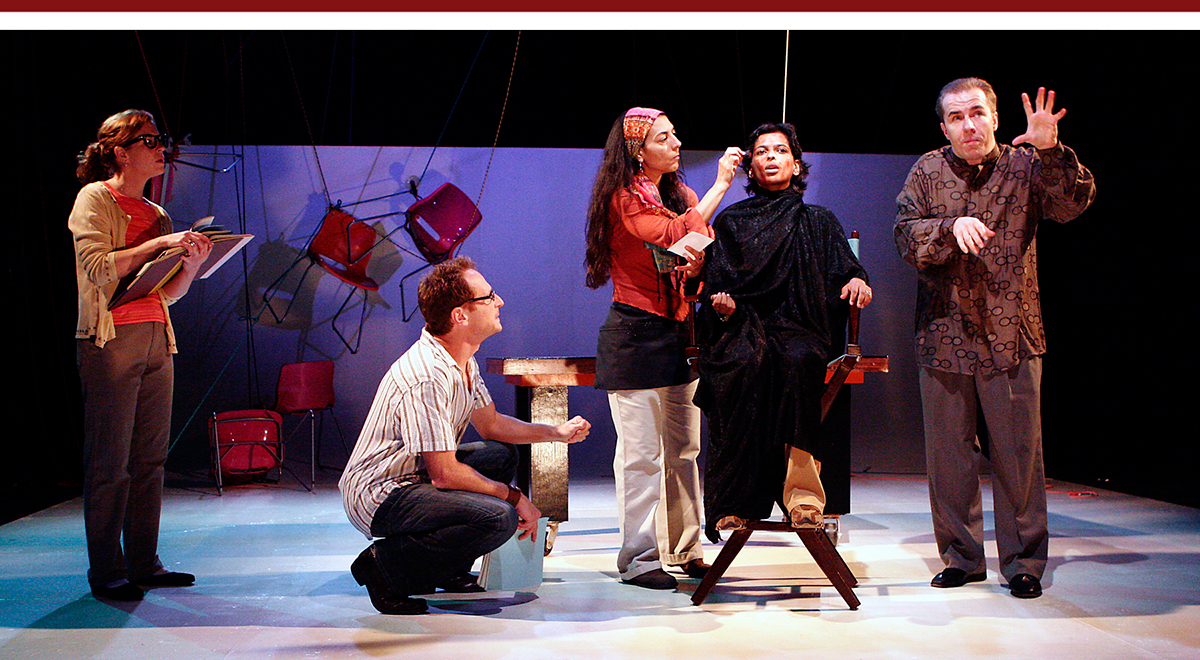

Leonard Roberts, Merle Dandridge, Moe Daniels, and Ken Barnett

Michael Lamont

Quantum Leaps

Stealing syntax from Shakespeare: To tell (of the thing) while being (the thing), that is the challenge. To explore notions of chaos theory and quantum mechanics while applying them to a dramatic narrative is to trek into worlds unknown. Fortunately, there’s an Unknown Theater Company – and the nominal yin to its yang, the Evidence Room – to co-welcome such a play to L.A. After premiering at London’s Royal Court, Martin Crimp’s Attempts on Her Life was ushered into America at SOHO Repertory by its Artistic Director Daniel Aukin (The Adding Machine). Now through December 15, it's here and in good companies, co-directed by the two artistic directors: Unknown’s Chris Covics and ER’s Bart DeLorenzo.

The co-production, in Unknown’s space at Seward and Santa Monica, mixes in-house members with new blood from ER. It’s a positive match, as the acting is stronger across the board than in Don’t Look Now, our only earlier Unknown evening [review]. Performances always engage, whether in the big, symmetrically positioned musical numbers – a sassy "Camera Loves You" occurs four scenes in while the punky "Girl Next Door" hits four scenes from curtain – or the intimate one and two-actor scenes. Tom Fitzpatrick and Kathy Bell Denton ground a flighty "Mom and Dad" while Eve Sigall beautifully renders the centrally placed fulcrum of "Kinda Funny."

The effect of Attempts is to send viewers sifting through 17 scenes spread over 90-plus minutes. Like investigators looking for threads in a debris field, we find numerous clues and a range of styles by which to collect them. The core thread is Ann, Annie, Anya, Anny – or perhaps just "an." She may be a person who inspires works of art; she may be a work of art; she may be an artist. Or, she may be all of them. It's not clear if our Anne is the genuine article or the indefinite one. She may have suffered molestation as a child and entered the sex trade in her teens before proceeded to a life of international terrorism. She may have picked up a husband and two kids along the way and dreamt it all.

The craquelure lens through which we perceive the events may make us bug-eyed with alternatives, but that’s the thrill of the ride. An older couple, speaking on behalf of her parents, describes the attempts that Annie has made on her life. She has been seen carrying a large satchel full of rocks guaranteed to drag her under. On the other hand, it may be that these "attempts on her life" are the attempts by artists to create "her" through film, theater and literature. The attempts were no accident, say the surrogate mom and dad. "Her mind was made up." Of course, that merely confirms the ambiguity that she could be a person committed, or a person contrived.

Art is art and life is life, as one character suggests. The closer to the randomness art becomes, the closer to life it is. To this end, something seethes in Crimp’s play like a monster caught in the rib cage. It seeks to break the conventions that hold a story back and cover its audience in something authentic – like what’s found on the back seat of auto Anny. It’s all too complex and in a state of emergence. The collaborative aspect of theater, as in the script conferences that bookend the show – "Tragedy of Love and Ideology" and, briefly to kick off the closing, "Previously Frozen" – are hilarious examples of contributed ideas becoming increasingly meaningless as they add up.

The audience has to work to hear the connecting principles that wind around Crimp’s litter-strewn canvas. Some scenes are intentionally hard to understand: simultaneous translation interferes, or singers spew dialogue like chunder, or pre-show loudspeakers play informative tapes that are talked over. But it’s okay. Folks should not expect to get it all in one pass, or be frustrated when they don’t. Like a piece of music, it would benefit by repeat plays. And, for those of us who just have to – though it is perfectly acceptable that the answers be left unknown – the Unknowns are present after the show. They come off the stage and hang out in the front-of-house lounge, breaking down the final wall in art-life intercourse that mixes the ambitions of a lofty avant garde with the accessibility of a neighborhood clubhouse.

top of page

ATTEMPTS ON HER LIFE

adapted by STEVEN EPP

and DOMINIQUE SERRAND

from La Fausse Suivante by Marivaux

directed by DOMINIQUE SERRAND

UNKNOWN THEATRE / EVIDENCE ROOM

November 10-December 15 (rev’d 11/18)

CAST Lauren Campedelli, Liz Davies, Kathy Bell Denton, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mandy Freund, Craig Johnson, Kelly Lett, Dylan Kenin, Taras Michael Los, Leo Marks, Uma Nithipalan, Dan Oliverio, Chris Payne, Eve Sigall, Brittany Slattery, Don Oscar Smith, Diana Wyenn

PRODUCTION Chris Covics, set; Suzanne Scott, costumes; Tony Mulanix, lights; John Zalewski, sound; John Ballinger, music; Brenda Varda, musical direction; Diana Wyenn, choreography; Beth Mack, stage management

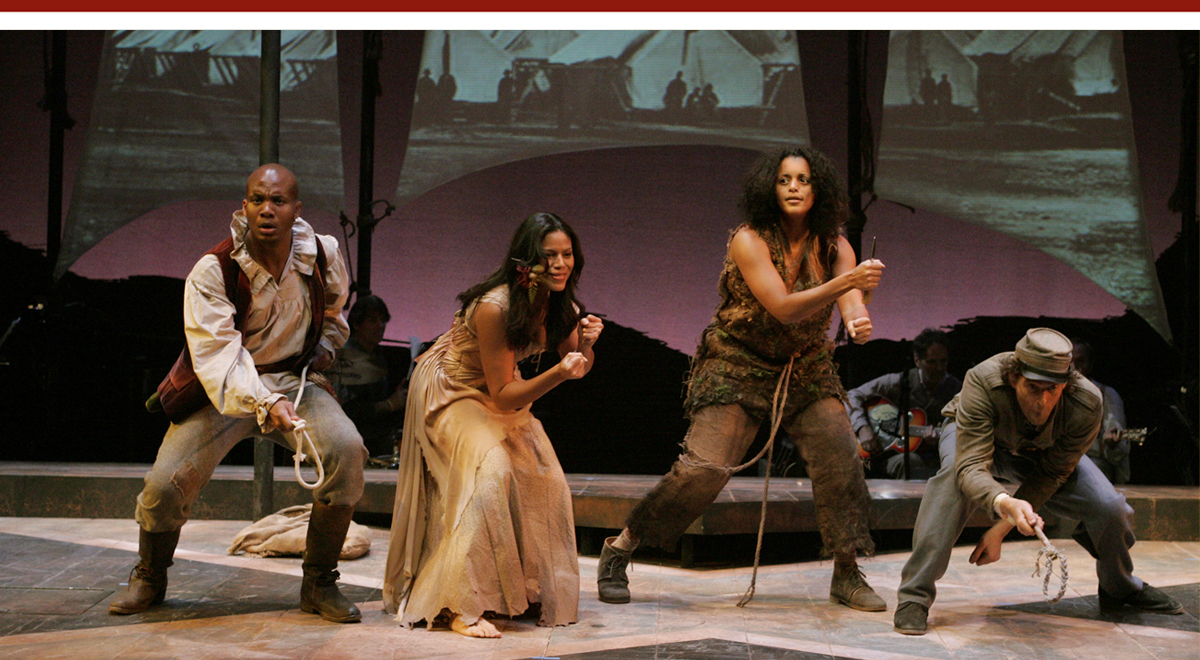

Mandy Freund, Leo Marks, Lauren Campedelli, Uma Nithipalan and Taras Michael Los

Chris Covics

Waterworks

It requires intelligence to make mindless entertainment entertaining. It takes genius to turn a one-dimensional "Romeo and Juliet go too camp" into the spirited imagination-fest now receiving its world premiere at the La Jolla Playhouse (through December 16). In a send-up of juveniles – equally poking fun and celebrating – this hugely entertaining version of John Waters’ Cry-Baby follows Avenue Q into the giddily subversive new genre of "musical delinquency."

The six-person creative team is comprised of librettists Mark O’Donnell and Thomas Meehan, "songwriters" David Javerbaum and Adam Schlesinger, choreographer Rob Ashford and director Mark Brokaw. Waters, an American phenomenon for style over substance, created the film version in 1990 to celebrate his own coming of age in the bifurcated social milieu of Baltimore. There, in the early ‘60s, the division of cool and clod was clear. The Drapes were the leather-jacketed juvies who thumbed their noses at authority while inspiring the coolest literature, music and films. The Squares were . . . well, square, inspiring little beyond the Individual Retirement Account and mild salsa. The film inspired "cult classic" status for those who like their comedy laid on the broad way. Despite the enormously talented Johnny Depp and more odd cameos than great-grandma’s jewelry box, the camp and the conflicts never rose above carnival din.

So, how nice that musical theater, which ranks only slightly higher up the cultural scale, would prove such an exhilarating fit for the story of Wade "Cry-Baby" Walker (James Snyder) and Allison Vernon Williams (Elizabeth Stanley), two Baltimore "youts" from opposite sides of the track marks. Credit the creative team with script and score than never wallow, never preach, and never fail to have fun. Cry-Baby manages to give truancy true class.

Wade Walker, a water-based name invoking Holy Roamers (while his creator’s name is rough translation for eau de toilette), is an orphan, rising through hard luck. The most charismatic of a motley crew of outsiders, falls for Allison at the annual Anti-Polio Picnic (which sets up the opening song as it raises a cleverness high bar that is maintained for two and half hours and two acts). From there, as Waters admits in wonderful director’s cut commentary, "it’s the Romeo and Juliet story."

Whereas Cry-Baby’s antecedent, West Side Story, is happy to resonate with social issues of gangs and ethnic disharmony, Cry-Baby is brazenly free of deeper meaning or significance. Even plot lines touching on capital punishment are immediately undercut. Any moral compass that might once have been inserted into the show has since been stomped beyond recognition by dancing motorcycle boots. (A fine ensemble exercises Rob Ashford’s choreography, but key kudos to an amazingly energetic trio of male dancers – Charlie Sutton, Spencer Liff and Eric Sciotto.)

As the leads, Snyder and Stanley are fine, looking and singing the parts with gusto and range. However, they’re unlikely to inspire idolatry. They’re beautiful and deliver the goods, particularly Snyder. But there’s a star quality that eludes them. Some of Stanley’s lines in fact blurred somewhat and were hard to glean.

While they admittedly have less to do, it was a bunch of second bananas who threatened to steal the show. Alli Mauzey is Leonore, a thankless character in the film and the only character who manages to fall through the crack between the Drapes and Squares. In a one-song psychotic sampler that out-Catherine’s Molly Shannon’s famous erotic-neurotic, Mauzey takes a small role and makes it rich. Same thing for Christopher J. Hanke, the latest glint-toothed Do-Right in a long line of blue-bloods from Animal House to Wedding Crashers. As the Square who misses the boat and loses the girl, Hanke makes a perfunctory role fun. At our performance, he was pushing his character’s boundaries by show’s end. But at this point in the run, it’s as excusable as it is irresistible. Mauzey and Hanke show star power without outshining.

Also show-worthy are Chester Gregory II as the conked and pomped Dupree, the black member of the Drapes who gives Cry-Baby its shot at soul. But while Gregory likely has the goods, the opportunity to show the music’s inherent power feels restrained. Harriet Harris offers a nice turn as Mrs. Vernon Williams, hitting all the notes from wacky grand dame to regretful accessory in Cry-Baby’s misfortune.

The visuals, created by Scenic Designer Scott Pask and Costumer Catherine Zuber, keep coming like clowns out of a Volkswagon. One remembers from Simone Marchard how much room there is beyond the upstage wall. One imagines this show nearly filling that space with a Rose Parade of parked set pieces. By the time we get to the environment for the jewelry-shopping fantasy, we’ve lost count of the environments – many for a single scene.

As was mentioned earlier this month in the review of Ray Charles Live!, there’s one noticeable drop-out in these rock ‘n’ roll musicals, and it’s the rock ‘n’ roll music. We don’t need redeeming social signficance, but shaving the accents off those lamé rockers leaves them pretty lame. Dupree’s singing is prettier than it is provocative and Cry-Baby’s best Elvis moment, "Baby, Baby . . . " is the show’s weakest number, partly because it fails to shake, rattle or roll. The music behind the Drapes should be louder and more raw.

But then, would it work on Broadway? Considering the generation that made Black Sabbath millionaires has reached the 60s, it should. Maybe this show could have it both ways: promote a split Saturday Night Special Schedule of 5 and 9 p.m. performances, with the second show 50% louder, and 100% rougher. Delnquency dies hard in Drapists.

As the title indicates, the same spring air that sows romance in some produces an allergic reaction in others. This Hay Fever is catchy, but unlikely to inspire wedding bells or runny noses.

top of page

CRY-BABY

Based upon the Universal Pictures film written and directed by John Waters

book by MARK O'DONNELL

and THOMAS MEEHAN

songs by DAVID JAVERBAUM

and ADAM SCHLESINGER

musical direction, incidental music, and

additional arrangements by LYNNE SHANKEL

choreography by ROB ASHFORD

orchestrations by CHRISTOPHER JAHNKE

dance arrangements by DAVID CHASE

directed by MARK BROKAW

LA JOLLA PLAYHOUSE

November 6-December 15, 2007

(Opened 11/18, rev’d 12/2e)

CAST Chester Gregory II, Christopher J. Hanke, Harriet Harris, Carly Jibson, Lacey Kohl, Alli Mauzey, Cristen Paige, Richard Poe, James Snyder, Elizabeth Stanley

ENSEMBLE Cameron Adams, Ashley Amber, Nick Blaemire, Michael Buchanan, Eric Christian, Colin Cunliffe, Joanna Glushak, Michael D. Jablonski, Marty Lawson, Spencer Liff, Courtney Laine Mazza, Mayumi Miguel, Tory Ross, Eric Sciotto, Peter Matthew Smith, Allison Spratt, Charlie Sutton, Stacey Todd Holt

PRODUCTION Steven Gold, music co- producer/arranger; Scott Pask, sets; Catherine Zuber, costumes; Howell Binkley, lights; Peter Hylenski, sound; Tom Watson, wigs/hair; Rick Sordelet, fights; Mahlon Kruse/Richard Rauscher/Jenny Slattery, stage management

James Snyder and Elizabeth Stanley

Kevin Berne

Say can you see

Gordon Hirabayashi grew up just like millions of first generation Americans. His parents leaned on the language of their homeland but learned English as they insisted it be their children’s native tongue. He embraced his country’s freedom of religion and association, both of which he grounded in the Quaker concept of friendship. He would pursue both education and romance as a free man, not as some gerrymandered hyphenate. However, as with all people of color in America, otherness would be forced back upon him from birth, and his calling card in society would be his genetic code.

Then, with the outbreak of World War II, he and his family, his community and the Japanese American population, would be further ostracized, distanced from all other immigrant segments and citizens of color. In response to attacks by the nation of Japan, naturalized and native-born Americans of Japanese descent were uprooted and boxed away in rough camps hidden in inhospitable areas across the country. Ironically, Hirabayashi's ingrained reverence for his country – or at least its stated principles – only deepened under the indignities and, after first becoming an obstacle to the incarceration process, he would become an advocate for the trampled U.S. Constitution, eventually standing for justice before the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court.

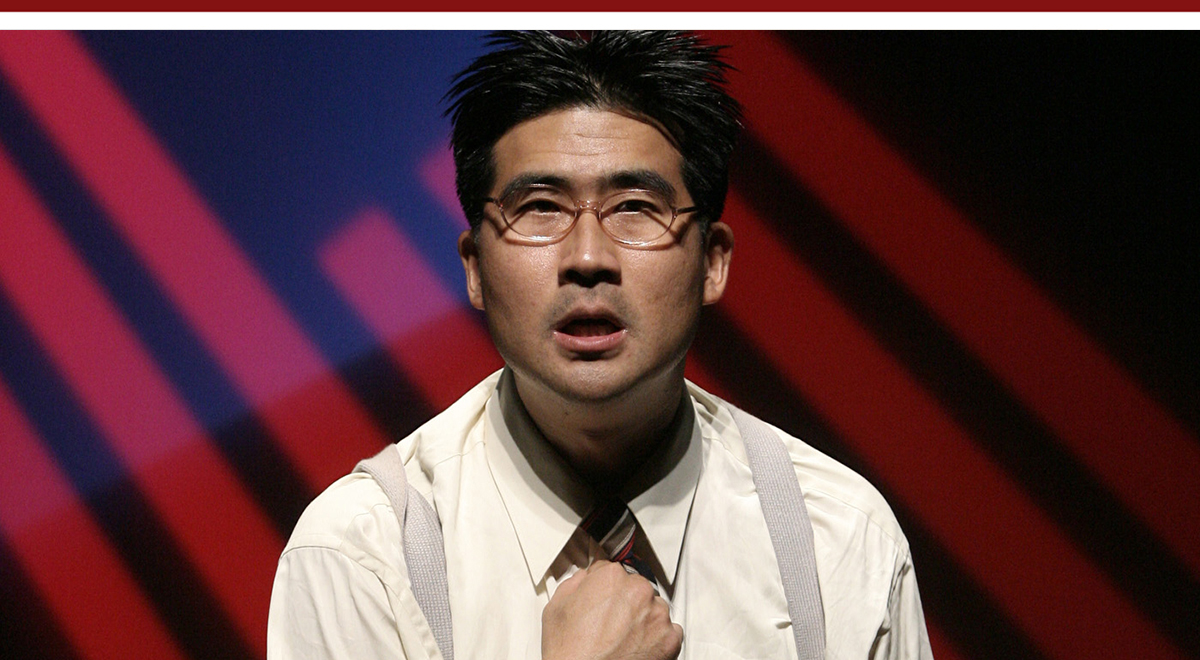

In Dawn’s Light: The Journey of Gordan Hirabayashi, receiving its world premiere at East West Players through December 2, first-time playwright Jeanne Sakata turns this extraordinary story into a detailed play for one actor. A faithful and inventive staging by Jessica Kubzansky sets up a showcase for the considerable talents of Ryun Yu, who inhabits Hirabayashi as well as the male and female people who played roles in his life.

Dawn’s Light is set upon Maiko Nezu’s visual haiku. Simple, textured lines full of resonance set off an upstage surface where beautiful black and white photography unobtrusively assists the storytelling. Yu himself does the minimal set adjusting: sliding an angled panel of rough wood from use as a sign to a position as the wall of his internment quarters or court chamber. The two wooden chairs that he frequently rearranges recall the unflinching simplicity of Quaker design and philosophy.

The label that this is "inspired by a true story" seems to be more for legal than literary purposes. As Sakata explains in a program note, Dawn’s Light "is a work blending historical fact with fiction, and certain actual events have been compressed or altered in terms of chronology or content for dramatic purposes." While such disclosure could give detractors a toe-hold on dismissal, there is little indication that the key dramatic events that stretch this 95-minute one-actor one-act have compromised the scope or importance of what is being described.

Sakata has set herself a significant challenge and realized it in great measure. However, even at an hour and a half, and despite the always-engaging work of Yu and Nezu’s and Kubzansky’s images and ideas, it falls into a midsection slowness that suggests there may be 10 minutes worth of pruning to be found in the narrative folds. Reducing use of the hindering device which requires Yu to play both sides of Gordon’s conversations with others, would also speed things up. Where possible, converting those exchanges into longer monologue passages that reveal plot, ideas, prejudices, etc. through character would break things up. It would also give Yu deserved breathing room to ripen these other voices into individuals. He already does a lot fleshing out what he can within the quick-change rhythm of "he said, she said" back-and-forths.

That said, the play and production are a beautifully realized window into a scandalous episode of hypocrisy. Sakata’s intersecting of Quaker and American ideals juxtaposes two systems that are inherently about equanimity. The haunting opening, made almost hypnotic by John Zalewski’s sublime sound design is one of those great coming together moments in theater: Yu’s no-nonsense delivery, softened by the actor’s easy accessibility, presenting Sakata’s serious exploration of the idea of "self-evident" truths, within a visual context of art-museum beauty is unforgettable. Not surprisingly, it returns to bookend the show.

These scenes, like the show as a whole, not only encourage us to better see the crime done to the Japanese-Americans of the mid-20th Century, but also to look past them to the horizon ahead. The framers of the constitution chose those words "self-evident truths" carefully. In a sense it was a way of exonerating themselves as revolutionaries: "We’re not making this up: everybody knows it." Well, everybody knew it was wrong to intern Japanese Americans 60 years ago, and everybody knows it’s wrong to incarcerate people without charges today. And, it will always be wrong to engage in systematic torture of prisoners. It’s never just about the accused. It’s about the accuser, too. As Sakata’s title allows, collective consciousness may never proceed past the state of mere dawning. But it’s for the artists like her, Kubzansky and Yu, to make sure our focus is drawn in the direction of the light.

top of page

DAWN'S LIGHT: THE STORY OF GORDON HIRABAYASHI

by JEANNE SAKATA

directed by JESSICA KUBZANSKY

EAST WEST PLAYERS

November 1-December 2, 2007

(Opened, rev. 11/7)

CAST Yu (Martin Yu, u.s.)

PRODUCTION Maiko Nezu, set/projections; Soojin Lee, costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; John Zalewski, sound; Nate Genung, stage management

PRODUCTION World premiere