OCTOBER 2006

Click title to jump to review

BACH AT LIEPZIG by Itamar Moses | South Coast Repertory

FENCES by August Wilson | Pasadena Playhouse

NOTHING SACRED by George F. Walker | South Coast Repertory

OTHELLO by William Shakespeare | The Old Globe

SONIA FLEW by Melinda Lopez | Mark Taper Forum

O

Fugue in the key of futility

O

Itamar Moses has a fascination with religious, civic and musical organization, from the creator standpoint as well as from the performers' perspective. He also has a catholic taste for theatrical styles – mingling sacred symbolism with schtick that would be home in the borscht belt or 1980's 'Airplane.' In ‘Bach at Leipzig’ -- at South Coast Repertory through October 15 -- he has created a lengthy fugue in the key of futility. And, if its strange blend of the ridiculous and the sublime feels much longer than any musical piece it purports to resemble, it is ambitious and worth a listen.

For those a little foggy on the composition of the Holy Roman Empire, Martin Luther's 95 Theses, and the work of 18th Century German composers, a little pre-show study of the online source material and program notes may enhance the experience.

There’s a matrix behind all this as keen as the vanishing-point template of Thomas Buderwitz's set design, drafted with Masonic precision by SCR's Production Department. That matrix is a cross-hatching of religious perspective and musical theory. In the interstices we catch references to free will, predestination and determinism, and their musical counterpoint.

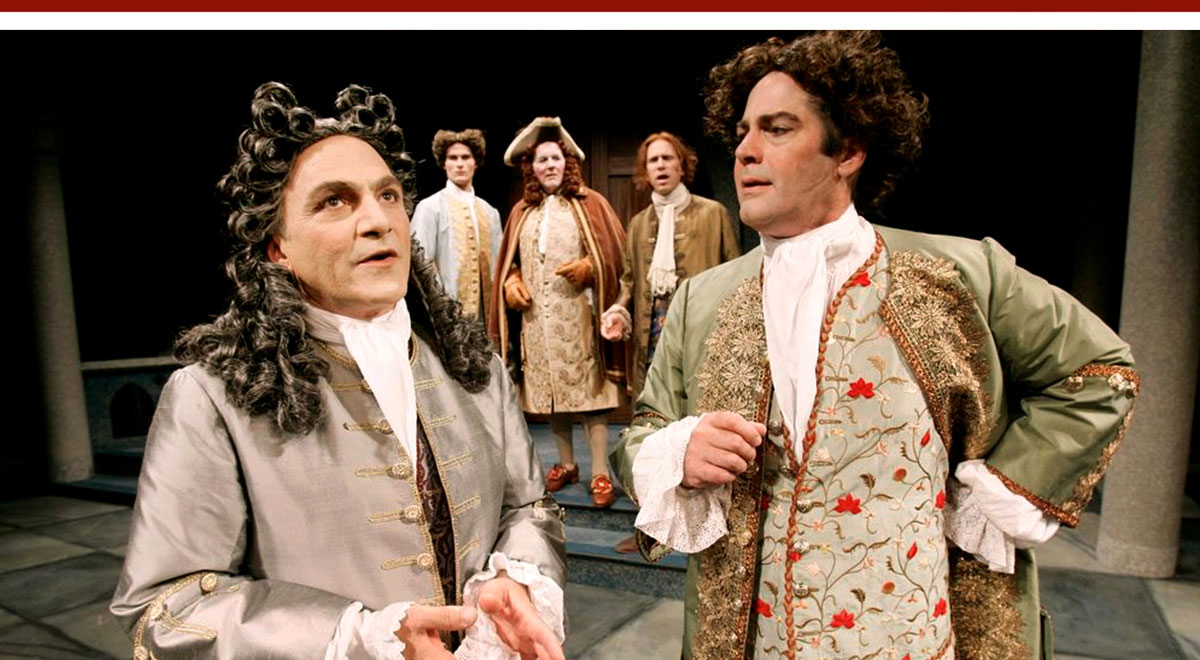

Art Manke helps his all male cast generate individuality in characters cut from sections of the same cloth. (Which makes this a good point to mention that Maggie Morgan’s costumes are exceptional: Were there royalty in Orange County, and I’m not saying there isn’t, they could hardly be better appointed than by Morgan and the SCR Costume Shop.) Not only do all the characters have the same goal, they all have the same willingness to break the rules to achieve it. They all resort at one time or another to the vaudevillian, slapstick energy that one expects to open into a rondelay of the “Vessel with the Pestle/Chalice in the Palace.” At those times, the beat in Moses’ mosaic is less baroque and more the hip-hop of antic silent film comedy.

Like an entire roomful of men crossed between the also-ran Salieri and always under-foot Venticelli, the six characters in ‘Bach’ are in search of fame and fortune. But once we realize that not one among them is named Bach, we sense that our elaborate plot is taking place in the same netherworld to which Stoppard cast out his outcasts from ‘Hamlet.’ In fact, after two-and-a-half hours of strutting and fretting, our court jesters are revealed as mere extras in someone else's drama. And who among us won't find that a relevant message?

Playing the piece are a cast of fine actors, lead by Stephen Caffrey in his SCR debut. As the character with the most time spent addressing the audience, Caffrey has the advantage of being the audience’s window into the shenanigans. He and Tony Abatemarco are the central pair. Hutchinson, one of the region’s finest, plays it well, but he’s confined by Moses’ hamster-wheel mechanics. Special note to John-David Keller for his role as a befuddled contestant, who not only gets the most exercise – making entrances up through the trap – but gives a wonderful false sense of a play within a play, and a better sense of a purpose in this one.

top of page

BACH AT LEIPZIG

by ITAMAR MOSES

directed by ART MANKE

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 24-October 15, 2006

CAST Stephen Caffrey, Tony Abatemarco, Jeffrey Hutchinson, Erik Sorensen, John-David Keller, Timothy Landfield, Sean H. Hemeon

PRODUCTION Thomas Buderwitz, set; Maggie Morgan, costumes; Geoff Korf,

lights; Tom Cavnar, sound; Darin Anthony, asst. director; Erin Nelson, stage manager

Tony Abatemarco, Erik Sorensen, John-David Keller, Jeffrey Hutchinson and Stephen Caffrey

Ken Howard

O

Out of the park

O

Troy Maxson, the man at the center of August Wilson’s ‘Fences,’ has disappeared. Whoever he should have been is lost behind the effects of a lifetime of diminishment. It’s buried like a storm grate beneath the refuse he has trapped and held, unable or unwilling to let it pass.

At the Pasadena Playhouse (through October 1), Laurence Fishburne plays Maxson as a man that, despite flare-ups about injustices at work and his sons, keeps the lid on what's left of his emotions. With the help of a weekly pint of afternoon gin, which he shares with his co-worker friend Bono (Wendell Pierce), and the love of his devoted wife Rose (Angela Bassett), Fishburne's Maxson appears to have reached an uneasy truce with the world. But anger is a toxin that doesn't weaken because you've bottled it up inside. And Maxson is being quietly poisoned by his.

Fishburne draws Maxson in normal scale, an average man who for various reasons was prevented from achieving more. At 53, limited by income and outrage, he spends his years like a broken thing in his neat backyard -- the show's one set, designed by Gary L. Wissman and lighted by Paulie Jenkins. He was a promising ball player who had a dazzling career in the Negro Leagues. But that left him off the radar of mainstream society and out of reach of lucrative contracts. That Jackie Robinson has broken through and now other blacks are playing is of little comfort. When Rose tells him he was 'too early,' he wisely replies, 'There ought never have been a time that was too early.'

'Fences,' which remains August Wilson's biggest money-maker, won a Tony Award and a Pulitzer. It put Wilson on the road to becoming one of the Century's great American playwrights, a place he would easily attain by the time his 10-play Pittsburgh cycle, and his 60-year lifespan, were completed.

But after experiencing Wilson's craft and vision strengthen in the remaining plays of his ten-drama play-per-decade survey of the 20th Century African American experience, 'Fences' can be seen in hindsight as one early step in his development. It's impact in the 1980s underscores the absence of storytelling of this calibre and subject matter from the literature of the American theater, as well as the special place in theater history occupied by James Earl Jones.

Director Sheldon Epps and his cast can do no wrong. Sold out houses and standing ovations were a certainty as soon as the contracts were signed. But audience and critical embraces do not necessarily mean that this is Wilson's finest work or its finest work-out. Despite the obvious fireworks when called for, there is a flatness here that emphasizes some of the script's creakier turns. When he tells his 34-year-old son Lyons (Kareem Hardison in the night's most successful turn) about a pivotal moment with his own father, it hardly has the gravity of such a seminal event. (Although Hardison, to his credit, tries to react as if it is, he has no where to go.) Nor is there a feeling of significance to match the story when he confesses to Rose that he has had an affair that will soon produce a child. When he summons up baseball analogies to explain what is a lackluster mid-life crisis, it fails to land in fair territory.

Maybe it was an off night. Maybe it is Fishburne's choice to stifle Maxson somewhat in response to all that's been heaped on him. That certainly makes sense, if not great drama. Others in the cast fall under similar fog. Bassett, whose character is written -- like Elizabeth in 'Salesman,' which this play honors with certain echoes -- as a reactive personality. Her only moments of gumption are in response to something, or, if she's launching a defense, it's on behalf of her undeserving husband. As Maxson's damaged brother, Gabriel, Orlando Jones acts the infirmity more than the man (although he tackles the play's demanding string of final outbursts beautifully). As Bono, Clark is solid. And, as the love child, Raynell, Victoria Matthews is lovely.

The play no doubt felt different with Jones at the center. His monument of a man is still felt even when scaled down to normal size. He may explain why this play had the extraordinary power it must have had. The great tragedy of the play is that Troy not only loses his soul to America, he becomes its agent of repression. His sons sense change and want to try for their own stardom through music and sports, as their father did with baseball. But he does nothing to support them and everything to stop them. He thinks he will save them from pain and indignity by sheltering them from a world that "won't let you get ahead." Instead, as his father did to him, he merely inflicts greater pain than the world could ever do. His attempts to limit them are symbolized by the fence he is building to enclose the back yard. "Why don't you help me build this fence?" he blindly asks his younger son Cory (Bryan Clark).

To see broken man come to such an end is a terrible indignity, and one that was played out regularly in yards like this across America. To have seen how it turn Jones inside out would have been an earth-shaking experience. The fall of that Troy, like some magnificent god shackled and broken, would have resounded with a message that a century of persecuted Americans – and the countrymen responsible for it – still need to hear.

top of page

FENCES

by AUGUST WILSON

directed by SHELDON EPPS

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

August 25 through October 1, 2006

CAST Angela Bassett, Bryan Clark, Laurence Fishburne, Kadeem Hardison, Orlando Jones, Victoria Matthews, Wendell Pierce

PRODUCTION Gary L. Wissmann, set; Dana Rrebecc Woods, costumes; Paulie Jenkins, lights; Pierre Dupress, sound

Angela Bassett, Laurence Fishburne, Wendell Pearce

O

Nothing much

O

South Coast Repertory opens its 43rd Season with George F. Walker’s ‘Nothing Sacred,’ a theatrical retelling of Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev’s (1818-1883) most famous novel, ‘Fathers and Sons’ (1862). Martin Benson directs the play, which was chosen in part to honor the heavily Russian-themed opening ceremonies of the Renee and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall next door, which includes a three-week residency by the Kirov Orchestra, Opera and Ballet of the Mariinksy Theater in St. Petersburg.

Hopefully the visiting Russian artists will take advantage of this opportunity to see the Tony Award-winning neighbor honor their country’s literary history. The play, without some sense of the historical context and/or novel, is less powerful as a stand-alone. Any adapter who takes novel to stage struggles to capture the expansiveness of a lengthy written narrative while honoring the kinetic requirements of a successful stage drama. In renaming the play, Mr. Walker, one of Canada's most successful playwrights, hopes audiences will see this as its own work. If you have not read the novel, SCR's online Study Guide (provided here) and one's own research will allow audiences to explore the source material to consider what might be missing.

As the opening salvo of the season, the words 'Nothing Sacred' – which refers 19th Century nihilism (from the Latin word for 'nothing') – echo the rallying cry that launched South Coast Repertory more than four decades ago. The company was committed to an unflinching, relentless exploration of the world through its art. Not one thing would be off limits. No thing would be spared.

The sense that this is a vital, urgent story about exciting ideas that are as relevant today as when the play is set is palpable in all its trappings. However, having ideas at the center of drama requires engaging side stories. Just as the adapter balances the storytelling demands of novel and stage, the director balances the thoughtful expression of the play's politics and philosophy with its romantic and dramatic elements – the former’s protein borne by the latter’s starch. Benson and his cast keep these agendas in healthy equilibrium as dialogue about obsessive beliefs shift smoothly to scenes about romantic obsession. Benson does as much as he can to have both sides standing at the final curtain. But Walker has delivered Turgenev's pairs of lovers as a series of lopsided affairs in support of the politics. In each case, one lover is hot with desire while the other is merely cool with a kind of willing complicity. In one case, both are cool and calculating.

Passion's touchstones are meant to be fired by ideas, which is again a challenge better met on the page.

Embodying this shifting demand for passion and philosophizing is an ensemble of solid actors who generally rise to the challenge. Most impressive is Eric D. Steinberg in his first lead role at this theater. In one of the finest male performances in memory, Steinberg appears to be Yevgeny Bazarov, a brilliant medical student who is equally adept at attracting men to his nihilist theories as he is at attracting women to his side. He seems to have been born off-book for this role, just speaking his mind as others render the lines of their script. The best of the rest is the titanic John Vickery as Pavel Kirsanov, the chief foil for Bazarov. Seduced by Western ideas, which makes him the character closest to Turgenev's personality, he has virtually lost interest in his own country's affairs. Vickery's gift for puff and swagger does more good than harm to his scenes. On the occasions he lets himself play to scale, he shows why he’s one of theater’s treasures. Also firmly grounded is newcomer Angela Goethals in a small role as a lower class house-keeper suddenly elevated to peerage by the infatuation of the estate's owner Nikolai Kirsanov (Richard Doyle). A third rail to Walker's script is its comedy, which acts as a break from the love and logic rather than in support of them. It is sometimes incongruously silly. However, anytime Hal Landon Jr. plays deadpan comedy in straight-man partnerships with the masterful Vickery and Doyle, is a good day.

Daniel Blinkoff, as Kirsanov's son and heir, is less successful. A style of airy concern and yearning is established in his first encounter with injustice, and it is ridden -- with little veering -- through scenes with his father, his uncle, potential lovers, and finally his dying friend. Khrystyne Haje, in her second SCR outing, does fairly well with a part that has not been given the meat it needs to stand alone. Despite her self-concept, Anna Odintsov remains a creation in service of male character's plots rather than her own woman.

Another asset is the physical production, which in typical SCR fashion calls upon the nation’s or region’s great talents: Jim Youmans, Angela Calin and Michael Roth are foremost at hiding the seams between reality and art.

All in all a genial welcome to the guests from Russia and a sturdy contribution to the Segerstrom Center for the Arts' addition of a new concert hall. And, a veiled reminder to those who would assume Western ideals and dress are an automatic fit for Asian countries, as the Shah found out too late and George W. Bush has found out but not acknowledged.

top of page

NOTHING SACRED

by GEORGE F. WALKER

directed by MARTIN BENSON

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 8-October 8, 2006, 2006

CAST Daniel Blinkhoff, Richard Doyle, Angela Goethals, Jeremy Guskin, Khrystyne Haje, Jeremy Peter Johnson, Hal Landon Jr., Jeff Marlow, Isaac Nippert, Eric D. Steinberg, John Vickery

PRODUCTION James Youmans and Jerome Martin, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes; York Kennedy, lights; Michael Roth, music

Eric D. Steinberg, Daniel Blinkoff

Ken Howard

O

More like it

O

The two questions that for four centuries have had audiences shaking their heads as they exit ‘Othello’ are first how a dominant military mind like Othello’s could be completely outflanked by his aide Iago, and second what stokes Iago’s hatred for the person who can do him the most good? The confusion persists not because directors are unable to answer the mystery but because the mystery is the answer. The black that is central to this play is not the Moor’s skin but the darkness that overtakes the human heart when righteous indignation ignites the right mixture of insecurity and pain. With Jonathan Peck as Othello and Karl Kinzler as Iago, the heart of Jesse Berger’s Old Globe staging (in repertory on the Lowell Davies stage through October 1), is a perfect pitch.

Othello is a powerful soldier, a proven leader of men. He is an ebony island in a sea of white foam. An outsider who circulates at the center of power, he is both wondrous special and wondrous strange. Peck’s Othello exults in his other-ness. Like the great Jack Johnson a century ago in America, Peck’s Othello outran the race issue long ago. He has now fallen in love with and married Desdemona (Julia Jesneck), the most desirable young woman among Venetian nobility. But while Desdemona reflects his specialness, the men of court cannot avoid reflecting on his strangeness. Othello shows no outward sign of distance from these men, but his suspicion of them is revealed in one important way. He will limit his ultimate trust to only one of them. Unfortunately, the one he has chosen has, for jealousy or rage, long been looking for the means to destroy Othello. And the marriage provides the opportunity.

Iago, although frequently portrayed as a bitter, older man, is in fact only 28. "I hath looked upon the world four times seven years," he says in the third scene. Kinzler’s Iago feels youthful. He springs about, engages in clowning with the foolish Roderigo, and when Othello seizes up and falls into unconsciousness, Iago is then seized by childish giddiness. And yet, Kinzler’s Iago bears a loathing that is as ancient as evil, all the more frightening for the way he masks it. It's an eerie reminder of our contemporary murderers who inevitably earn their neighbors' back-handed praise: ‘He’s always been so nice. I can't imagine him doing this.'

Desdemona is radiant in the early going and properly distraught in the final scenes. She must accommodate her lover’s sudden shift from love to loathing, which seems a plot stretch, except to those who have personally experienced the man they married turn abusive for no apparent reason.

Ralph Funicello’s simple set allows us to move from promenade to office with the drawing of a drape and the shift of a light. Its stately architecture, overlain by Julia Cho’s vivid costumes and York Kennedy’s warm lights – note the use of a white light to accentuate the skin on Desdemona’s first entrance -- allows Berger some elegant stage pictures (although in some of the later scenes of violence the static posing undercuts the call for chaos). There’s an unfortunate choice to end the production with a fairly cheesy bit of melodrama∫, which provides a new reason for head-shaking upon our exit. The final image of a tethered Iago firing off his evil cackle reminds that evil may be captured but never destroyed. Here, however, evil may truly be having the last laugh, and spoiling an otherwise exquisite evening.

top of page

OTHELLO

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by JESSE BERGER

THE OLD GLOBE

June 23 - October 1, 2006

CAST Matt Biedel, Chris Bresky, Chip Brookes, Celeste Ciulla, Bayardo DeMurguia, Wynn Harmon, Rhett Henckel, Dan Hodge, Charles Janasz, Julie Jesneck, Leonard Kelly-Young, Karl Kenzler, Michael A. Newcomer, Jonathan Peck, Summer Shirey, Michael Urie, David Villalobos, Leah Zhang (in for Aaron Misakian)

PRODUCTION Ralph Funicello, sets; Linda Cho, costumes; York Kennedy, lights; Christopher R.

Walker, sound; Steve Rankin, fights; Jan Gist, speech; Dakin Matthews, dramaturg

Karl Kenzler, Julie Jesneck and Jonathan Peck

Craig Schwartz

O

Arrival and departure

O

In ‘Sonia Flew,’ receiving its West Coast premiere at the Laguna Playhouse through October 15, Actress-Playwright Melinda Lopez has something to say about religious traditions, war and tyranny. But she shows them from both sides of the double-pained window between adolescence and adulthood. And from that perspective, those big-ticket themes are just window-dressing for the issue that really fascinates Lopez: at what point do we take control of our lives from our parents? And who’s to stop us from throwing our lives away if that's what we choose to do with them?

The play is divided between America after 9/11 and Cuba before the Bay of Pigs invasion. The game board the playwright sets up for the first act is closed at intermission and reopened like an asymmetrical inkblot for act two. In this way, the title character stands firmly on both sides of the threshold – as parent and child – and in both instances Sonia is the loser.

Lopez strikes the right balance between the political and the personal, allowing the smaller human dramas the greater weight. This is not a play about the horrors of Castro or socialism, or the failed policies of the Bush Administration. For contemporary audiences, those issues are self-evident. For future generations, future wars will refresh the idea that parents protect their children from dangers to hold them close and children embrace dangers to escape their parents grasp.

It’s also refreshing to have Lopez give these debates balance, not tipping the scales to one point of view. However, this combined with keeping the play of free of specifics about wars, attacks, invasions and so on gives the big confrontation scenes a sameness that reduces them to a series of loud squabbles. To minimize that effect, director Juliette Carrillo tries to make up time early, leaving the balance of the play to proceed at a comfortable pace. While this makes the characters appear too glib and the acting too shallow at first, it pays off by the end, when the personal cost of major political events is clearly and powerfully delivered.

The asymmetrical inkblot structure provides a nice challenge for actors, who generally play one role close to type and one further from it. Marissa Chibas has a token role in the first half before becoming a major player in act two. Casting Geno Silva as a Polish grandfather provokes head-scratching until the structure becomes clear in act two and he plays a Cuban father. Matt Gottlieb as an ineffectual Jewish dad becomes a sneaky Cuban neighbor. Christian Barillas, the tortured act one son seeking his parents’ approval before going to war, becomes a less conflicted enlistee in Cuba's youth corps. Tanya Perez creates an uninteresting daughter in act one, before returning as the more complex – and better written – young Sonia in act two. And Judith Delgado, who seems to be pushing the age limit on Sonia as an adult, is the anachronistic servant in Castro's Cuba. Together, Perez and Delgado connect Sonia from childhood to adulthood and to those of us watching.

When Carrillo gets the pace under control we clearly hear what Lopez has to say. Even in this early stage of her development she has good instincts for what matters and an admirable sense of balance to encourage contemplation rather than blast over it with her opinions. In the end, when the board is closed again and the rules of the game understood, we see that winning requires letting go and forgiving. Even if that means we lose what we most want to hold onto.

top of page

SONIA FLEW

by MELINDA LOPEZ

directed by JULIETTE CARRILLO

LAGUNA PLAYHOUSE

September 12 through October 15, 2006

CAST Christian Barillas, Marissa Chibas, Judith Delgado, Matt Gottlieb, Tanya Perez, Geno Silva

PRODUCTION Myung Hee Cho, set; Joyce Kim Lee, costumes; Lonnie Alcaraz, lights; David Edwards, sound; Chris Webb, music

HISTORY West Coast Premiere