OCTOBER 2007

Click title to jump to review

A CATERED AFFAIR by Harvey Fierstein and John Bucchino | The Old Globe

KISS ME KATE by Cole Porter and Sam & Bella Spewack | Civic Light Opera of South Bay Cities

OSCAR AND THE PINK LADY by Eric-Emanuel Schmitt | The Old Globe

QUALITY OF LIFE by Jane Anderson | Geffen Playhouse

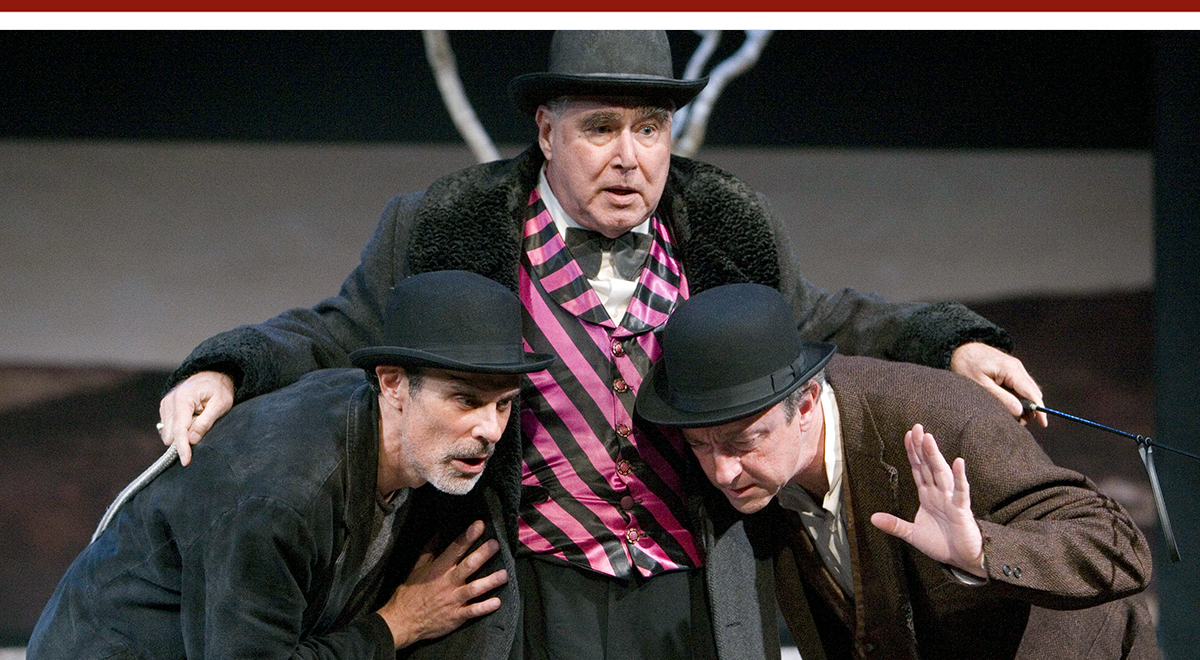

WAITING FOR GODOT by Samuel Beckett | A Noise Within

THE WINTER'S TALE by William Shakespeare | A Noise Within

The Bronx-Brooklyn local

Dinner plates pass easily across a table in A Catered Affair, the promising new musical by Harvey Fierstein and John Bucchino premiering under John Doyle's direction at The Old Globe (through November 4). Beneath the surface, however, the tectonic generational, domestic and spousal plates are shuddering and seizing under mounting resentments over uncredited sacrifice and accommodation. And before anything can be digested, the family structure is going to be forever shaken.

A Catered Affair is a small story in a marquee production. Its paternity is packed with heavyweights; its cast with headliners. Paddy Chayefsky originated the story as a 1955 teleplay before adapting it with Gore Vidal for a 1956 film. In this theatrical adaptation, scheduled for a spring 2008 Broadway bow, Fierstein and Bucchino continue that small-screen focus with a simple plot and setting. Fierstein's book is aware of social upheaval, but it keeps its eyes on the fault lines in the shrinking Hurley family. Likewise, David Gallo's evocative scenic design stays within 45 color-wheel degrees of nostalgic sepia. And Bucchino's wonderful score and lyrics never stray too far from speech. Consequently, they weave in out of the dialogue as gracefully as a piano accompanist supporting a cabaret singer.

It is 1953 and those in charge of America's homes are children of the Depression entering a new age of middle class affluence. This turns households into pressure-cookers that will form both the diamonds and dirt clods known as Baby Boomers. War in Korea has just cast a dark shadow across the Hurley home with the recent death of a son. Daughter Janey (Leslie Kritzer) awakens one morning beside her boyfriend, Ralph (Matt Cavanaugh), whom she has secreted into her bedroom. A driven, new generation girl, she bullies him to agree to a next-day civil ceremony so that by week's end they can drive a friend's car to California for their honeymoon. They'll return soon enough and pick up their lives as newlyweds.

Her folks, Aggie (Faith Prince) and Tom (Tom Wopat), a pair still numb from the loss of their only son, are given the news as non-negotiable. The old "if we invite one we'll have to invite everybody" logic means that Janey's "bachelor uncle" Winston (Fierstein), staying with them while he sorts out a lovers' spat, won't make the cut.

A shotgun wedding (even when it's the bride-to-be with the itchy trigger finger) still merits a meet-the-in-laws dinner. So Ralph's wealthy REALTOR dad (Philip Hoffman) and mom (Lori Wilner) come to break bread that very night. There's typical tension in the air: cash-strapped Tom sulks when Mr. Halloran offers the kids a free lease in a fancy neighborhood; Janey bites her tongue as Aggie harps on the merits of big, catered weddings. But the tension is bearable until a snubbed and loaded Winston arrives. Now it's temblor time.

As source material, the messy real world of family relations is a hornets' nest that can excuse a lot of odd twists. So, does it make sense that Janey, to save a few hundred dollars on a trip to California, will piss off her future rich in-laws? Especially when no one seems to be requiring a marriage license for the road trip? Add haven't the neighborhood gossips (Heather MacRae, Kristine Zbornik and Wilner) probably put the news of Ralphís morning exit on the wire already? Does it make sense that Janey will cave in so easily when she sees what the absence of a fancy wedding is doing to her mother? And will her dad wait and wait and wait to speak his mind about how ludicrous this all sounds to him?

Sure. Sounds like home to me.

Where the play is weakest is along its tangents: Tom and the Hallorans. What's the nature of Ralph's attraction? This is a low-rent, unglamorous choice for a handsome heir apparent. And why doesn't Mr. Halloran have more grit? If for no reason than to add drama. He's little more than an ATM. Tom is also fairly one-dimensional. For now, it's the women (and Winston) who drive the show. Filling in the three male characters might be done in a single pre-dinner scene between Ralph and the fathers. Investigating the conflicts of being men at this pivotal time, of sacrificing a son to this new (and continuing) form of war, or just wrestling with the mysteries of women would be interesting, flesh out all three, and let Bucchino add a male trio to his score.

And perhaps the neighbor ladies, who are there to add voices as well as the threat of disclosure and disgrace, need to be more threatening and less fun if they're going to inject any danger.

Among the actors, Faith Prince shows why she's a star. Honoring her character's habit of keeping the lid on by not overreaching in performance, she gets away with some of the longest takes you'll ever see. They are lovely, and a credit to Doyle and her that such stillness can reach those lengths. Wopat is appropriately world-weary, holding fire as long as he can and erupting in character. The underused Cavanaugh shines in his brief moments while Kritzer creates a Janey believable as overlooked for a son.

And then there's Harvey. It takes some doing to adjust one's inner ear distortion filter and hear what those rock quarry vocal cords are putting out. From his first appearance, behind the mini-curtain-raising of a kitchen shade, he delivers a big performance that tilts the aesthetic turntable whenever he's on stage. Yet, we grow accustomed to his voice, and he renders tender moments for the show's coda.

The plot questions probably matter more to dramaturgs and critics than they do to Broadway audiences. What those folks want a show to provide are hummable tunes. And Bucchinoís score, as appropriate and beautiful as it is, may be what earns Catered Affair a chilly reception. Whether Fierstein and Bucchino cave in and cater to the expectations of their future guests is unknown. But it will surely be reported by Gotham's growing horde of Internet gossip-mongers.

top of page

A CATERED AFFAIR

book by HARVEY FIERSTEIN

music and lyrics by JOHN BUCCHINO

directed by JOHN DOYLE

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

September 20-November 4, 2007

(Opened 9/30; rev. 10/7e)

CAST Matt Cavenaugh, Harvey Fierstein, Philip Hoffman, Katie Klaus, Leslie Kritzer, Heather MacRae, Faith Prince, Lori Wilner, Tom Wopat, Kristine Zbornik

MUSICIANS Ethyl Will, conductor/piano; John Reilly, Deborah Avery, Scott Reese, reeds; Karina Bezkrovnaia, Erica Erenyi, Ted Hughart, strings; Frank Glasson, Allan Grant, horns; Jeff Dalrymple, percussion

PRODUCTION Don Sebesky, orchestrations; Constantine Kitsopoulos, musical direction and incidental music; David Gallo, set; Ann Hould-Ward, costumes; Brian MacDevitt, lights; Dan Moses Schreier, sound; Zachary Borovay, projections; David Lawrence, hair; Claudia Lynch, Tracy Skoczelas and Heather Weiss, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Matt Cavanaugh, Leslie Kritzer and Faith Prince

Craig Schwartz

Cast of the Mojicans

Directors, adapters and actors have been trying to corral Shakespeare's shrewish Katherine since the Bard penned her in the 1590s. In Cole Porter's Kiss Me Kate, the Tony Award-winning Best Musical of 1949, the clever composer-lyricist corners Kate in a play within a musical. However, it's not done to explore her complex power as much as show off his. So it is that Kiss Me Kate, uninterested in what's behind Shakespeare's slap-fest, aims to be just a good-natured hit parade, and in director-choreographer Dan Mojica's staging, the folks at South Bay Civic Light Opera get that in a walloping production that delivers the tunes handsomely.

In Kiss Me Kate, antagonistic husband-wife theater stars Fred Graham (Kevin Bailey) and Lilli Vanessi (Michelle Duffy) are co-starring in a Baltimore production of Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew. Their backstage bickering parallels the action of the play's protagonists: Katherine, the feisty "no-man-can-win-me" spinster in the making, and Petruchio, the stallion who partly for the challenge and partly for the cash prize woos, weds and then subjugates her. Silly plot points abound in Baltimore. There's little to explain the stars' love-hate teeter-totter, which flaps with abandon. Then there's fellow cast member Bill Calhoun (John Bisom), who, after we're shown that nobody backstage can spare two dollars for his cab fare, discloses that his mob debt hit $10,000 overnight. To avoid a beating he had signed Graham's name to the chit, freeing himself for the musical's second tier love story with a big-dream chorine named Lois Lane (Lesli Margherita). The gambling story is there only to usher two mob henchmen-with-hearts in to shadow Fred, right through wardrobe and into Shrew's Elizabethan setting. Mojica's thugs are Jeffrey Landman and mile-high Herschel Sparber whose Mike Mazurki-mug makes him a wonderful throwback to the period.

As Kate, the beautiful and beautiful sounding Duffy is back out front as she was in her Ovation-nominated role as Pistache in David Lee's recent Can-Can at the Pasadena Playhouse, which, she helped turn into this year's most-nominated show. There, where Lee's zesty imagination lifted the whole production over the book's rough spots, we could only pick nits with the story and some of the characterizations. Here, where the timeless art is only in Porter's music and dancing, Mojica frets even less with what's behind the motivation and focuses on staging one winning production number after another. The whole show – from the gathering storm of "Another Opening, Another Show" to the rousing "Kiss Me Kate" reprise – is always picture-perfect, alive with energy and clockwork precision, and invests the choreography with the snapped steps and gestures of tightly rehearsed, talented dancers who are all on the same pages.

But when we get to the relationships, they're pretty cartoon-y. The challenge for Bailey and Duffy is that they have to navigate their hop-scotching emotions without a lot of text support. The tunes arrive like points of interest on a highway: signs begin to appear that something is coming up and suddenly it's time to pull over for a number.

The dashing Bailey, whose singing voice is superb, has an acting voice ready to announce a Bonus Round! Still he can perform wonderfully, as in "Where is the Life That Late I Led?" Duffy, for all her charms, can't give much dimension to Kate, which, admittedly, given the layers of dual character and sexual compromise, can be somewhat forgiven. But her solo on "I Hate Men," for instance shows her breadth of talents. Bisom, despite owning the ability to pin his IOU on his friend, strikes the most natural balance between the demands of musical theater and the nascent potential for character. Meanwhile Margherita, without missing a note or step, finds plenty of comedy to mine with an irresistible packaging of Gracie Allen timing in a Dolly Parton carton, exemplified in "Always True to You in My Fashion."

This is a good time in the music hall. Very talented performers under the direction of a real pro. And, as a bonus, producer James Blackman, who puts every other pre-show subscription pitch to shame, welcomes the audience with tuxedoed stand-up that turns the gathering into a party and makes the whole affair even more forgivable.

top of page

KISS ME KATE

by COLE PORTER

book by SAM & BELLA SPEWACK

musical direction by ALBY POTTS

directed and choreographed by

DAM MOJICA

CIVIC LIGHT OPERA OF SOUTH BAY CITIES

September 26-October 14, 2007

(Opened 9/29, rev. 9/30)

CAST Kevin Bailey, Michelle Duffy, John Bisom, Lesli Margherita, Shell Bauman, Brad Delima, Lateefah Devoe, Jay Donnell, Jeff Griggs, Jeffrey Landman, Herschel Sparber, Bart Williams, Chris Acuff, Samantha Berman, Jennifer Brasuell, Allison Eberly, Brad Fitzgerald, Zuri Goldman, David R. Gordon, Merissa Haddad, Barrie Linberg, Joseph Marshall, Lauren Masiello, Heather Mieko, Chuck Pelletier, Kaci Wilson

PRODUCTION Christopher Beyries, set; Martin Pakledinaz, original costume design; Darrell Clark, lights; John Feinstein, sound; Deanne Johnson, hair/wigs; Craig A. Horness, stage management

Michelle Duffy and Kevin Bailey

Signing off

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt was a doctor of philosophy before he was a playwright. For Oscar and the Pink Lady, now through November 4 on The Old Globe's Carter Stage, under the direction of Frank Dunlop, his inner dramatist creates a multi-stage delivery system for what his inner philosopher is wrestling with. Together, they have come up with a self-asphyxiating structure by which to offer some benign and not very interesting ideas about matters of life and death.

The channeling begins with Good Philosopher Schmitt, who employs the talents of Schmitt the Playwright to create a mouthpiece out of a dying 10-year-old boy. It's a small aperture of consciousness that, for even the most elastic suspenders of disbelief, will feel too constricting. The boy, Oscar, adds another chain to the communication linkage by putting his thoughts into words via a series of letters to God, written at the suggestion of "Granny Pink." Pink, who has become very close to Oscar during the period diarized in the letters, is one of the volunteers at the Children's Hospital where he knowingly spends the last days of his short, cancer-riddled life. "Granny Pink" gets in line as the reader of the letters, not so much interpreting them as acting them out. And finally, Granny Pink is in turn interpreted by the Tony Award-winning Rosemary Harris.

So it is that Oscar and the Pink Lady, except for Pink's brief introductory and closing addresses, is a two-hour, two-act play ostensibly written by a 10-year-old.

It's a nice idea and fertile with irony: two friends at opposite ends of life wrestle with the impending death of the wrong one. Furthermore, Michael Vaughn Sims creates a linoleum checkerboard, ringed with stenciled childhood images, upon which to play it. But Schmitt has strapped himself with his epistolary conceit. Not only does it challenge – and somewhat befuddle – Dunlop and Harris in terms of clarifying the play's voice from moment to moment (especially when Granny is quoting Oscar quoting their conversations together), in theory it limits the breadth of the play's vision and its author's vocabulary. (It worked with Anne Frank because she began writing at 13, and continued until her death at age 15.)

Because Granny Pink takes such natural ownership of the storytelling, Schmitt can push the envelope a little and we're not that bothered by a 10-year-old using phrases like "Treated me impeccably." But there are many examples beyond arguable maturity levels in the language. He easily grasps things Pink or the doctor tell him and then articulates them in his writing. Stéphane LaPorte translated from the French, and may have helped or hurt Schmitt in the choice of words.

All of these mechanical quibbles would be less urgent if what we find when we work our way back through Schmitt's game of telephone was more interesting. The principal thrust of the letter-writing is to confront God by way of an innocent child, assisted by someone seven or eight times his senior. But not until Pink takes Oscar to the hospital chapel, and then only briefly, do we feel something is on the table. Otherwise, time passes and we literally count the days. Oscar has a relationship with another patient, a young girl whose main symptom is a bluish skin color. Thanks to a game Granny Pink comes up with, which is for Oscar to pretend he ages a decade a day, Oscar and "Peggy Blue" experience the romantic complexities of people in their 20s. Once Peggy is cured, and she briefly becomes a second Pink Lady, she is discharged, and Oscar returns to his decline.

In a context where a writer goes to these lengths to construct a new way to question God for either causing or merely allowing the innocent to perish, we don't walk out of Oscar and the Pink Lady feeling like any serious interrogating occurred.

The circumstances may damn God, but not the writing. And neither does Harris' performance hint at righteous indignation. Instead, it is filled with a kind of puckish élan. True, that is her impression of Oscar. But it might have been a more dramatic experience if Pink was able to speak for herself directly rather than be channeled exclusively through the boy's letters. One wants a little fist-shaking. Instead, we wait patiently, ticking off the days in hope of the big pay off: some real purging and insight, or just heartbreak. But, it never comes.

There is no reason, given Ms. Harris' capabilities, that Oscar and the Pink Lady couldn't approach a kind of Scholastic Book-level version of Margaret Edson's Wit. There are huge, wrenching questions that can be wrestled with. The only question here is whether Schmitt the Philosopher or Schmitt the Playwright will be the one standing with Ms. Harris at curtain call. True, a half-dozen audience members did require tissue at play's end. But there should have been a lot more. On the whole, Schmitt lets those watching -- beginning with God -- off pretty easily.

top of page

OSCAR AND THE PINK LADY

by ERIC-EMANUEL SCHMITT

translated by STEPHANE LAPORTE

directed by FRANK DUNLOP

THE OLD GLOBE

September 22-November 4, 2007

(Opened 9/27; rev. 10/7m)

CAST Rosemary Harris

PRODUCTION Michael Vaughn Sims, set; Jane Greenwood, costumes; Trevor Norton, lights; Lindsay Jones, sound, Monica A. Cuoco, stage management

HISTORY American Premiere

Rosemary Harris

Craig Schwartz

Controlled burn

When a world premiere has a marquee cast with the star power to pull the magnetic strip off a credit card, ticket buyers need only minimal assurance of script quality to let the plastic fly. Rest assured, Jane Anderson's The Quality of Life, at the commissioning Geffen Playhouse through November 18, is a worthy showcase for the substantial talents of Scott Bakula, Dennis Boutsikaris, Laurie Metcalf and JoBeth Williams.

That should be all a curious theatergoer – especially those age 50 and above – needs to hear. Further details would only diminish the experience. Also, chances are tickets could sell out in the time it takes to read the rest of this review. But we will continue: Quality control demands we provide more than a three-sentence review.

For this first Geffen commission to reach the boards, writer-director Anderson has packed a 20-unit survey of contemporary life into two acts and two hours. With dramaturgical alchemy she integrates a multitude of thorny issues into Quality of Life. At the top of the list is the obvious Kevorkian context of weighing the options of living with disease. But clear yardsticks are laid down everywhere against which we might measure what feels like every aspect of our lives: the quality of our marriages, religious faith or resistance, lifestyles, environmental sensitivity, appreciation of parenting, and our sense of social justice and leniency. Even our responsibility to personal and community legacy.

The playwright has created characters that clearly represent distinct choices made in these many areas. However, with thanks in great part to the fine acting, they come across as typical folks and not as types. The actors simultaneously focus our attention on their micro-stories while letting universal meaning ripple out.

Anderson builds this instrument of observation upon the various inter-relations of two couples. Connected through the wives' shared grandmother, they are distanced by 2,000 U.S. highway miles and diametrically opposed beliefs in how to cope with good and evil, randomness and determinism, and perhaps even life and death.

Homemaker Dinah (Williams) and homebuilder Bill (Bakula) live in Ohio, mired in a threadbare marriage that lost its cover a year earlier with the torture-murder of their college-age daughter. They are as strong as they expect they ever will be again, having rebuilt their psyches with the unyielding materials their church provided. A rare letter from Jeanette (Metcalf), explaining that Neil (Boutsikaris) is in a losing battle with cancer, prompts Dinah to insist that the housebound Ohioans pack for a weekend out west.

The minutes-long Ohio scene is prelude. The bulk of the play is set in the eerie campsite that used to be Jeannette and Neil's mountain home in Northern California. In another brutal twist of fate, an accidentally set forest fire has turned it into a virtual lava-field. With a nomad's tent, an outhouse, bathtub and cooking station, they proudly show off their ability to survive simply and without possessions.

The strength of spirit with which they approach these devastations confounds the devout Bill, as does Neil's use of medical marijuana. Despite the placating Dinah's best efforts, the couples are able to share only hours before their differences make the reunion too uncomfortable.

Metcalf is back at the Geffen after her production-raising turn as Kate in All My Sons. If Arney can talk her into being a cornerstone of a Geffen acting company, we're in for some great years in Los Angeles. Boutsikaris, who was last at the Geffen in The Old Neighborhood, creates an indelible Neil. He becomes a man whose loss to students seems as significant as his loss to Jeannette. Bakula has the toughest assignment by far here and does a good job of walking the line between character and cardboard.

Williams is the real heart-breaker though. A too-familiar character in too many American homes, she begins as a human squeeze-toy in infinite need of one more hug. She delivers Dinah's speech of indignation beautifully. It's a sudden and rarely evoked blast of highly emotional articulation.

And, the final moments, as beautiful as they are, have not found their timing. As written and staged, there's some wobbling in the shifts between California and Ohio. Following the natural transition from lecture to Yurt and beyond, one wonders if moving the Ohio scene up would help. To save more time, the chairs could be part of the lecture stage before being part of the Ohio scene. Maybe at other performances the ovation comes without the curtain call cue coming up. If not, in a play where timing, and endings, are so integral, finding a way for artists and audience to arrive at their parting on the same wavelength – which we all were ready for – would be a great legacy with which to mark our brief time together.

top of page

THE QUALITY OF LIFE

written and directed by JANE ANDERSON

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

October 2-November 18, 2007

(Opened 10/10; rev. 10/13m)

CAST Scott Bakula, Dennis Boutsikaris, Laurie Metcalf, JoBeth Williams

PRODUCTION FranÁois-Pierre Couture, set; Christina Haatainen Jones, costumes; Jason H. Thompson, lights; Karl Lundeberg, sound; Amy Levinson, dramaturg; Anna Belle Gilbert, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

JoBeth Williams, Laurie Metcalf and Dennis Boutsikaris, top, and inset, Williams and Scott Bakula

Michael Lamont

God knows

The half-century-old Waiting for Godot has reached such status as a landmark of world drama that one imagines its premiere more like the unveiling of a Picasso or Pieta. But playwright Samuel Beckett did not pull the shroud off a fully formed work in 1953. He put his pants on one leg at a time like other playwrights, and launched his plays like them too: through a development process of trial and error.

As Johns Fletcher and Spurling write in their Beckett The Playwright, "The text now available was established only after a number of versions had been tried out. The original French manuscript is still unpublished, but enough is known about it to show that it was a rather hesitant piece of work: Beckett was not sure what names to give his characters, for instance, and even whether or not to make Godot a real presence in the action by suggesting, for example, that Estragon and Vladimir have a written assignation with him, or that Pozzo himself is Godot failing to recognize those he has come to meet."

This effort to normalize Godot somewhat is sparked by Andrew Traister's current staging at A Noise Within, where a solid cast and a great design provide easy access for anyone waiting for a Godot that invites understanding and enjoyment. The dramatist was going to some trouble to make sweeping assertions about how we live and probably wanted as many people as possible to pick up on them. Traister and company help make Godot fun and intriguing rather than foreboding and incomprehensible.

In the perfectly worn surroundings of the former Masonic Temple, Joel Svetow and Robertson Dean are Estragon ("Gogo") and Vladimir ("Didi"). Mitchell Edmonds creates a Pozzo that would make Mack Sennett weep in recognition. And, Mark Bramhall provides a perfectly ghastly Lucky – stabilized when saddled with baggage and bizarre when performing the life dance of one pitted at birth.

Michael C. Smith has given Traister and his actors a beautiful playing area: a rectangle of barren earth, raked and curling up to the distant vista, but not quite reaching it. This plot remains disconnected from the world.

The more enigmatic or ambiguous a work of art, the more we can stretch interpretation in a direction we choose. Sacred texts are the best examples of this, and indeed the sacred is part of Beckett's world. The Bible has an early citing. Whether Godot is a direct reference to God, however, will never be answered. And it would only diminish the play to do so. However, it is clear that if Beckett had not wanted "Godot" to be confused with "God," he would have given him another name.

The story of Waiting for Godot is so simple that it is infinitely complex. A pair of friends with frustratingly fickle memories (echoed in Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern) have arrived at the desolate spot where they "were told" they must meet Godot. While Gogo is the more forgetful, Didi is certain they have the appointment. He indicates that Godot is important, and infers that meeting him will be helpful. Or, perhaps it's that not meeting him will be a big problem. So they bide their time, clinging to their flimsy excuse for purpose, letting their hamster-wheel minds rattle away in confusion. Diversion arrives in the form of a man of position, Pozzo, driving an ancient servant, Lucky. Pozzo has purpose, but only so long as he has someone to abuse.

By the end of Act I a day has passed and Godot is a no-show. A boy (Alex Yeghiazarian alternating with Frankie Foti) brings Godot's apology and assurance he will arrive the following day.

A similar sequence, with the same outcome occurs in Act II, with the one difference being the hopeful appearance of foliage on the tree.

Much has been made of Beckett's wasteland, circular conversations, vanishing points and pointlessness. He paints a grim picture of the folly and crime inherent in the systems we structure to help us cope, understand and relate: The dim-witted will wander and the appointed powers will brutalize. There will always be masters and servants. And though they are ultimately clowns, they are nevertheless destructive.

Thank God for the clowns, though. Dean and Svetow help distinguish Didi and Gogo (with great assistance from costumer Angela Balogh Calin). Svetow is intense and worrisome; Dean is glum and thoughtful. The chemistry is something actors must bring to Godot and these two have an enjoyable mix. Their characters are not as frustrating as others often are. Edmonds, however, again establishes himself as one of the finer character actors in town. His Pozzo is marvelously rich. He can snap back and forth between the threat and the comic undercut like a master. Calin again serves him well, with a ringmaster's costume of jodhpurs with pink piping, a showman's vest and whip to invoke Beckett's circus theme.

Traister helps remind us that for all the ideas this play offers, the visual metaphor is of Vaudevillians yanked from their routine and dropped into an existential landscape without answers. Everybody's got to see Waiting for Godot some day. Traister makes this one rewarding. Edmonds makes it a treat. Don't wait.

top of page

WAITING FOR GODOT

by SAMUEL BECKETT

directed by ANDREW TRAISTER

A NOISE WITHIN

October 2-November 18, 2007

(Opened 10/10; rev. 10/13m)

CAST Mark Bramhall, Robertson Dean, Mitchell Edmonds, Joel Svetow

PRODUCTION Michael C. Smith, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes; James P. Taylor, lights; Byron Batista, hair/makeup; Yolanda A. BaÒos/Rache Berney-Needleman, stage management

Joel Svetow, Mitchell Edmonds and Robertson Dean

Craig Schwartz

The triumph of time

At the heart of Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale, like Othello, is the matter of jealousy. In both cases, the affliction that drives the play is made darker and more mysterious because it has taken over the heart of a powerfully independent man who has had an exemplary marriage to a truly adoring woman. In the earlier Othello, the audience is shown that the seeds of Desdemona's undoing are outside the marriage, in a plot devised by the man her husband trusts most. In Winter's Tale, now in repertory through December 8 at A Noise Within, there are no third-party machinations. Consequently, co-directors Geoff Elliott and Julia Rodriguez-Elliott have more latitude in providing the psychological underpinning behind Leontes' behavior.

Both plays are based on existing stories. Othello, inspired by Giraldi Cinthio's "Hecatommithi," was considerably altered for Shakespeare's purposes, including the Moor's sole responsibility for both his wife's murder and his own blinding. Robert Greene's "Pandosto" bears greater similarity to Winter's Tale, with one significant change. In The Winter's Tale, whose title may in part indicate that it is the view of an aging writer, the accused wife does not die and instead survives 16 years of exile to be reunited with a repentant husband.

Whether Shakespeare had become more forgiving near the end of his writing career or merely wanted his play to have a happy ending is unclear. But these two points – the mysterious cause of Leontes' jealousy and the way in which his wife, Hermione, will return to him – are key to what modern directors must grapple with in the telling of this strangely balanced tale.

The story begins with Leontes (Elliott), the king of Sicily, emploring his childhood friend Polixenes (Stephen Rockwell), now king of Bohemia, to extend his visit. Leontes' wife Hermione (Jill Hill), picking up the party line, also insists he stay. As soon as Polixenes acquiesces, Leontes feels threatened. Hill, who showed her range in brief roles in Ubu Roi and A Touch of the Poet, here appropriately entertains Polixenes as an extension of her husband's hospitality. Whether based in anything beyond good manners, the hostess' efforts seem to produce a chemical response from her guest. What should be a fair compliment for a wife and mother whom no man of lesser rank dare flirt with, becomes her undoing. Leontes completely misunderstands their friendship and goes off the deep end. Unlike Othello, he is on his own. In fact all the counsel Leontes receives adamantly defends Hermione. Nevertheless, the afflicted king will threaten his friend and his wife and anyone who sides with them. In the process, he will lose his young son and heir, convict and banish his wife, and disperse the closest members of his court. The baby that is born before his wife leaves, will be sentenced to die. It will take a disobedient subordinate to save the baby, leaving it for a shepherd in Bohemia to raise, and open up the pastoral change of pace that becomes Act II. While the daughter grows to womanhood, Hermione hides in the home of Paulina (Deborah Strang), allowing Leontes to assume she is dead.

The husband-and-wife directing team establishes Hermione as an innocent and Leontes as a closed-off man with a tendency towards madness. Elliott's most recent roles, the leads in Touch of the Poet and Man of La Mancha, also flirted with madness. Those two men were tilted by delusions of grandeur. Here, his character topples over completely under the weight of his savage obsession. Though we don't see a justifiable cause, we do see the effect, which play's into Elliott's wheelhouse and does explain the weaker than usual dramaturgy.

Hill meanwhile moves nicely from giddy hostess to blind-sided victim and finally, in the production's nicest touch, to indicate with a subtlety of tone and body language, that she won't be so quick to forgive.

Among the standouts in the cast are the always powerful Strang, a detailed dual-role from William Dennis Hunt, and the jolly shepherd of Mitchell Edmonds, taking a working vacation from his duties as Pozzo in Waiting for Godot, another production in the repertory.

While Soojin Lee's costumes are wonderful and Peter Gottlieb's lighting spot-on, Darcy Scanlin's set is problematic, which is ironic given how little there is of it. The use of angled floor-to-ceiling metal poles seems like one of those good-on-paper ideas that would be better in proscenium staging. With full-thrust stage and three-quarter surround audience, just about every actor is going to be obscured to some degree from at least someone at any given time. For this observer it was Hill's first downstage scene with Rockwell, which might have blocked the kind of stolen glance that would have changed the entire meaning of the play. Also, at this performance an actor clipped an angling pole while making a short cross and though he didn't stumble, he was probably a little frustrated. The best part of the set design is a simple double-projected Gobbo, that shows a broken mirror pattern, a nice invocation of the Shakepeare's notion of the mirror up to nature, and the shattered mind of the central character.

top of page

THE WINTER'S TALE

by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

directed by GEOFF ELLIOTT

and JULIA RODRIGUEZ-ELLIOTT

A NOISE WITHIN

September 22-December 8, 2007

(Opened 9/29, rev. 10/20m)

CAST Tom Beyer, Mitchell Edmonds, Alison Elliott, Geoff Elliott, Nora Lynn Frankovich, Miguel Angel Gallegos, Raymond Gaston, Jill Hill, William Dennis Hunt, Ross Kidder, Anne Goen Nerner, Stephen Rockwell, Lawrence Sonderling, Deborah Strang, Martin Swoverland, Steven Weingartner, with Nicholas Apostolina

MUSICIAN Endre Balogh, violin

PRODUCTION Darcy Scanlin, set; Soojin Lee, costumes; Peter Gottlieb, lights; Rachel Myles, sound; Monica Lisa Sabedra, hair/makeup, Rachel Myles, stage management