SEPTEMBER 2007

Click title to jump to review

THE ADDING MACHINE by Elmer Rice | La Jolla Playhouse

AND NEITHER HAVE I WINGS TO FLY by Ann Noble | The Road Theatre

ART by Yasmina Reza | Laguna Playhouse

AVENUE Q by Various | Ahmanson Theatre

CALLING APHRODITE by Velina Hasu Houston | International City Theatre

DURANGO by Julia Cho | East West Players

A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC by Stephen Sondheim & Hugh Wheeler | South Coast Repertory

MATTER OF HONOR by Michael J. Chepiga | Laguna Playhouse

SWIMMING TO THE MOON by Gary Flaxman | Art/Theatre

THIRD by Wendy Wasserstein | Geffen Playhouse

Nuclear family

A likely misconception at its beginning may actually be the intention of Julia Cho's crafty and well-crafted Durango, getting a decent West Coast premiere under Chay Yew's direction at East West Players (through October 14). The Mr. Lee being ushered from his office by a security guard is not the Mr. Lee who made international headlines when, according to The New York Timesem>, he was "dismissed from his job at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for violating security rules, but [not] charged with a crime."

The setting, we will discover, is Arizona, where Ms. Cho was raised, not New Mexico. But it ís close enough, and the circumstances are left unclear just long enough to let the danger of divulging national secrets set the stakes for a story about the danger of keeping family secrets. Ms. Cho, whose last Southern California production, The Piano Teacher (now scheduled for an off-Broadway bow at the Vineyard), also focused on long-harbored secrets and buried shame, shifts from that play's predominantly female voice to all male characters for Durango. This womanlessness, and the general sense that men are more closed off, allows the relationship of a man and his two sons a heart-breaking emptiness that is reflected in the desert they will drive through on a futile search of renewal.

Mr. Yew, a favorite collaborator of the playwright's, exhibits great understanding of Ms. Cho's purposes and strengths and provides a good staging, though there is likely a more definitive one waiting down the road. Nelson Mashita as Boo-Seng Lee must show and not show what's going on inside him and he does it well. As Isaac, the older, post-college first son now expected to enter Medical School, Jen Suh has depth and understanding of his character's quiet rejection of everything save his music (which Suh performs beautifully to start the show).

Ryan Cusino, however, doesn't provide enough real topography in the pivotal role of high-school-age son, Jimmy, whose academic and athletic achievements are all that validate Boo-Seng's sense of parenting skills. Cusino has the most emotional territory to cover as the family healer who also hides his own secret. He's a young actor who still needs to develop more variety and ease. An overused scrunching of the face to show concern, fear, confusion and more, restricts him.

Because his scenes with Suh flatten and fail to provide better balance, the hamster-wheel exchanges between Isaac and his father take on more prominence and leave the production with a harsher tone. As a kind of artist in making, Jimmy is a young Tennessee Williams trapped in a world of intolerance and anger. Without more light from Jimmy, we're left with only the intolerance and anger in the play.

That weakness may contribute to a sense that Ms. Cho's dialogue doesn't feel a perfect fit for the men's mouths. For instance, when Jimmy's behavior sparks epithets at him from a hardened Isaac, the use of the phrase "bright shiny new" in the middle of his outrage seems forced. But these are minor quibbles in another work from a thoughtful young writer who always merits viewing. Three brief scenes in which each male channels Mrs. Lee's personality in recollections showcase the naturalness of Ms. Cho's voice and, in the excellent Suh's scene, becomes a transcendent moment for the production.

In Durango, Boo-Seng Lee has been laid off after 20 years. To justify Lee's security guard escort (John Apicella) and invoke the aura of Los Alamos (though, the real Mr. Lee was not removed so gingerly), Ms. Cho has Boo-Seng mildly, yet uncharacteristically, assault the man who fires him (Alex Klein is good as Lee's boss and some fantasy characters in Jimmy's imagination.)

Mr. Lee is then unemployed, unmarried and unhinged. Without telling them that he was fired, he manages to get his sons to join him for an ill-conceived vacation to Durango, a Colorado tourist town that promises, according to its website, "beautiful scenery, historic charm, friendly faces." Mr. Lee has a long-held brochure. (There's a little cloudiness here as to whether he had been there, or wanted to go; and whether or not it was the scene of a tryst.) Despite his best efforts to maintain his image as a stern but fair father, he will slowly unravel under the weight of his loss, the growing distance between himself and his sons, and a deep secret he refuses to share even with himself. It's a lot of stuff to be churning inside this guy, more than is needed to make the point. But Ms. Cho likes big issues and continues to show she can juggle them handily, although subplots specifically about homosexual secrecy may challenge the theme of family honesty for the play's focus.

Much of the play is their road trip, nicely represented on Donna Marquet's set, with great use of video by Jason H. Thompson and a detailed sound design by John Zalewski (though, these days, using ringing phones to represent an office ambience may distract cellphone-packing audience members).

What the men find or fail to find is interesting and informative and in the hands of Ms. Cho and Mr. Yew it makes for a fascinating journey. Hopefully, we'll get to take the trip again someday.

top of page

DURANGO

by JULIA CHO

directed by CHAY YEW

EAST WEST PLAYERS

September 13-October 14, 2007

Opened 9/19, rev. 9/20

CAST John Apicella, Ryan Cusino, Alex Klein, Nelson Mashita, Jin Suh

PRODUCTION Donna Marquet, set; Dori Quan, costumes; Jose Lopez, lights; Jason H. Thompson, video; John Zalewski, sound; Seth A. Kolarsky/Sally L. Jacob, stage management

HISTORY West Coast Premiere

Jin Suh, Ryan Cusino, Nelson Mashita

Michael Lamont

The God smiles

South Coast Repertory opened its 44th Season Friday with its first large-scale musical since The Education of Randy Newman in 2000 and its first Stephen Sondheim show since Sunday in the Park with George in 1989. The latest, A Little Night Music (through October 7), should satisfy audiences as well as the institution's pursuit of great writing.

This 1973 collaboration between Sondheim and book-writer Hugh Wheeler (whose only other teaming was for the magnificent Sweeney Todd) followed Company (1970) and Follies (1971), and established him for many as America's greatest living theatrical composer. Here, under the steady hands of director Stefan Novinksi and musical director Dennis Castellano, Sondheim's genius is as brilliant and inviting as a lover's summer smile.

Sondheim unifies each score around a theme (here it's variations on the sophisticated, hypnotizing three-quarter meter of the waltz) while carefully fitting the lyrics to his characters. In the world he inherits from the inspiring Ingmar Bergman film, Smiles of a Summer Night, he molds his language to the personalities and stations within three Swedish households, and then creates a Liebeslieder quintet to serve as Greek chorus.

Dueling stereotypes of the cool, contemplative Swede versus the impassioned, free-thinking Swede lend themselves to some of Sondheim's greatest wordplay. The notorious puzzle-lover underscores those contrasting qualities with musical counterpoint that, for yet another dimension, recalls Mozart's "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" (which gives the show its title). One hears the editing in an over-deliberative man's admission that "I still want and/or love you," while jealousy rattles another man's saber and he loses confidence within a single sentence: "She wouldn't...therefore they didn't... So then it wasn't...not unless it...would she?"

Novinski has assembled a fine cast that let lyrics and dialogue spring from each as a unique soul.

The three groupings of characters are the acclaimed actress Desiree Armfelt (Stephanie Zimbalist), her dying mother (Teri Ralston), still bursting with memories of scandalous affairs, and her daughter (Kate Horwitch) a knowing yet innocent teenager. The home of middle-aged lawyer Fredrik Egerman (Mark Jacoby), consists of his 18-year-old bride Anne (Carolann Sanita), his melancholy son Henrik (Joe Farrell), and their maid, Petra (Misty Cotton). The third group are an openly adulterous Count (Damon Kirsche) and his brow-beaten but still-superior wife Charlotte (Amanda Naughton).

Fredrik and Desiree had been lovers, and although it is alluded to in Sondheim's most famous lyric ("Isn't it rich? Are we a pair? Me here at last on the ground, You in mid-air."), the circumstances of their parting aren't that clear. When a touring production starring Desiree comes through town, Fredrik is innocently confronted by the old feelings and visits her backstage, only to find she has become the latest conquest of the self-indulgent Count. Nevertheless, their easiness with each other soon leads to intimacy.

Stand-outs for this reviewer include Mark Jacoby as Fredrik, believably combining the awareness of his folly with the inability to resist it. His few interactions with Henrik set up a realistic relationship to create that hanging scion. Also, Amanda Naughton is wonderful as Charlotte. Naughton comfortably fills out her character's conflicted nature as one who makes the most of the game handed her, despite being surrounded by lesser players. Her sense of irony makes a song like "Every Day a Little Death" a special pleasure. As the Count, Damon Kirsche also moves seamlessly from dialogue through song, transforming the statements of an egomaniac into the colorful plumage of pomposity. All three are as strong and nuanced in their acting as in their singing.

Two performers who are stronger singers are Carolann Sanita as Fredrik's young wife, Anne, perhaps the finest voice on stage, and Misty Cotton, an earthy Petra who gives radiance to "I Will Marry the Miller's Son."

In the central role of Desiree Armfelt, Stephanie Zimbalist is a stronger actress, though still excellent, particularly when teamed with Jacoby for "Send in the Clowns," the show's (and Sondheim's) only hit. Zimbalist also has an uncanny resemblance to Teri Ralston, the great Sondheim veteran who is given the wheelchair role here. As Madame Armfelt she performs the bittersweet "Liaisons," another cherished Sondheim gem that stirs ember beds of memory that mix once-hot passions with cooling recollection.

If at times a little more urgency might benefit the staging, on whole the pace is balanced and appropriate. Choreographer Ken Roht, however, understandably hungry for something to do besides stage waltzes, has mixed success with some back-up singer pantomiming that is utterly out of step with the characters' individuality. (Unless "A Weekend in the Country" becomes "A Weekend in Gladys and the Pips.")

For those lovers of Sondheim who havenít hardened their minds around some past perception of perfection, Novinski, Castellano and company provide ample cause for waltzing. This wonder from a contemporary American talent who should be revered with the kind of awe given dead Shakespeares and Sibeliae, is especially beautiful displayed against Sibyl Wickersheimerís evocative set: A large, empty room where once extraordinary events offered embrace, now sits in need of freshness. It's a perfect backdrop for an evening where relationships end and memories begin.

In the meanwhile . . .

top of page

A LITTLE NIGHT'S MUSIC

music and lyrics by STEPHEN SONDHEIM

book by HUGH WHEELER

musical direction by DENNIS CASTELLANO

directed by STEFAN NOVINSKI

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 7-October 7, 2007

(Opened 9/14; rev. 9/15e)

CAST Christopher Carothers, Misty Cotton, Karen Culliver, Katie Horwitch, Joe Farrell, Mark Jacoby, Damon Kirsche, Ann Marie Lee, Tracy Lore, Branden McDonald, Kevin Mcmahon, Amanda Naughton, Teri Ralston, Carolann Sanita, Stephanie Zimbalist

ORCHESTRA Dennis Castellano, keyboards; Francine Walsh, violin; Nancy Stein, cello; Phillip Feather, flute/clarinet/oboe; Keith Bishop, clarinet/English horn/bassoon; Ellie Choate, harp; Timothy Christensen, bass

PRODUCTION JSibyl Wickersheimer, set; Shigeru Yaji, costumes; Christopher Akerlind, lights; Drew Dalzell, sound; Ken Roht, choreography; Jamie A. Tucker/Jennifer Butler, stage management

The cast

Henry DiRocco

Hazing

On August 31 the story of Johnson Chestnut Whittaker's years at the United States Military Academy arrived by stage in the Pasadena Playhouse premiere of Michael J. Chepiga's Matter of Honor. Directed by Scott Schwartz and continuing through September 30 it dramatizes events leading up to West Point's discharge of Whittaker, the sixth African American appointed there. This infuriating and instructive episode from the late 1870s was previously the focus of a 1972 book by John Marszalek and a 1994 docudrama from Showtime, both entitled Assault at West Point: The Court Martial of Johnson Whittaker.

According to a program ad, Chepiga's version is "a mystery inspired by the true story." Whether fictionalizing has enhanced or undermined the true story's impact is its own mystery. After researching the real-life Whittaker, however, facts that the playwright has chosen not to incorporate lead one to wonder if he has mined as much drama as he might have. Still, credit him with retraining a light on a form of stoic American heroism too long swept under the bunk; and credit the Pasadena Playhouse with handing him a high-voltage production for a torch.

Born a South Carolina slave in 1858, Whittaker attended West Point from his 18th birthday until his discharge in 1882. Politicians appoint cadets to the academy, and S.L. Hoge had promoted a man already proven at the University of South Carolina. At the university, according to Marszalek, he "had benefited from tutoring at the hands of Professor Richard T. Greener," the first African American to graduate from Harvard. The university's website refers to Greener as a professor of "moral and mental philosophy" who also taught international and U.S. Constitutional law.

Of the five black cadets who preceded Whittaker, all but Henry C. Flipper had been discharged. Except for a few months living with Flipper before he graduated in 1877, Whittaker was an island amid the white corps. He lived alone in a room meant for two men and was on the receiving end of "silencing," the practice by whites of not speaking to blacks other than at drill and ostracizing them to sit alone at meals and church services.

Early one morning in April 1880, Whittaker was found unconscious and bleeding on the floor of his room. His hands and feet were bound, and his ears had been sliced. A mirror had been broken over his head and a note of warning pinned to his shirt. Pages from the Bible his mother had given him were torn out and burned. Once revived, Whittaker reported to the school's officials that he had been blindfolded while sleeping and tortured by what sounded like three students.

To tell how the institution pursued the "mystery" of what happened and how it was decided to discharge Whittaker is the focus of Matter of Honor. Our guide is a fictitious investigator named Chase (Eric Lutes), who as the play begins is a broken alcoholic, wallowing in guilt over his participation two years earlier in concocting the rationale that Whittaker had staged his own beating to avoid an exam. Ironically, given his exposure to Greener, it was philosophy he was supposedly dodging.

Though Whittaker (Cedric Sanders) maintains a central place in the story, the focus is split between them and the dramatic arc and timeline follow Chase. The frequent back and forth in time, complicated by Chase's shifts in sobriety, make the role more muddled than it need be. Yet, Lutes gamely tries to center it along the moving target of time and temperance. He may also be holding fire in the performance to leave headroom for Sander's Whittaker to remain the star. Establishing a POV around a self-absorbed white accessory is an appropriate tact in America, though a surprising one at a theater that after 10 years of Sheldon Epps' Artistic Directorship has arrived as a prominent presenter – and now generator – of African American theater. The choice to give us a touchstone of one who like most whites in his position would probably just go along with the majority, hints at a play about the greater society's honor and integrity. But, again, the focus is not crisp enough for that to succeed.

Among the nuggets left out is the role of Greener, who would unsuccessfully represent Whittaker as legal counsel. That may be because the Showtime film already centered on Greener, played by Samuel L. Jackson, and his partner David Chamberlain played by Sam Waterston. There, Whittaker is even less central to the story.

The cast is good, with Brian Watkins, Steve Holm, John O'Brien and Ryan J. Hill, as the young white cadets, having the cleanest shot at nailing clearly drawn characters. As the more complicated General Schofield, another historical figure, Richard Doyle provides humanity for a man whose priority is the institution, even though that means divided loyalties for the young men who constitute it. As Whittaker, Sanders is boxed in with no other character to speak with honestly – the way Chase does with Stern (Adam J. Smith), the West Point representative who seeks him out and gets him re-engaged. Ironically, by not providing him such a sounding board, Chepiga manages to silence Whittaker once more. Still, Sanders does his best to let us see much of what is going on inside.

What should, first and foremost, be a riveting drama powered by language rich in texture and insight, is not inherently gripping and may appear to be leaning on the superb production values. Re-enactments of the beating, on a hydraulic platform enveloped in stage smoke, Hellish red light and piercing sound cues, can't compensate for a script that is not uplifting. Still, a creative team – led by Robert Brill (set) and Donald Holder (lights) – are, as the Board Chairman writes, "one of the finest ever assembled at the Playhouse." And, if you've brought a box of the finest fireworks to the picnic, it's crazy not to light 'em up.

Finally, a writer relying on such extensive text projections to fill in historical links and button up loose ends – in a play "inspired" by facts – may have a script tugging for another look. Though Chepiga is past the point of such radical restructuring, future writers looking for a guide into Whittaker's story may want to look to Whittaker himself as an older man. Research indicates that, far from being defeated by the mistreatment, as Chase was by his complicity, Whittaker went on to a career of service outside the military as an educator and administrator. Even though recollection structure is admittedly creaky, a proud and productive Whittaker, who died in 1931, could easily tell his story to a young man or woman who, we can imagine, would incorporate the story into his or her work. For instance, Ralph Ellison, who some researchers say was once a student of Whittaker's.

top of page

MATTER OF HONOR

by MICHAEL J. CHEPIGA

directed by SCOTT SCHWARTZ

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

August 24-September 30, 2007

Opened, rev'd 8/31

CAST Steve Coombs, Richard Doyle, Eric Lutes, Cedric Sanders, Adam J. Smith, Brian Watkins, with Steve Holm, John O'Brien, Ryan J. Hill

PRODUCTION Robert Brill, set; Maggie Morgan, costumes; Donald Holder, lights; Mark Bennett, sound/original music; Austin Switser, visual effects; Charles M. Turner III/Hethyr Verhoef, stage management

Eric Lutes, Richard Doyle, and Cedric Sanders

Craig Schwartz

ON THE REAL SIDE In July 1995, a year after the Showtime film aired, President Clinton presented an honorary Second Lieutenant's commission to Whittaker's descendants, 115 years after the court martial.

On August 9, 2007, the Washington Post ran the obituary of an 89-year-old retired Army Colonel named Clarence M. Davenport Jr. There in black and white, two weeks before Matter of Honor's first preview, was immediate connection to a play about something that happened 130 years ago. Davenport entered West Point in 1939, along with Robert B. Tresville, another black cadet. They "were not roommates," the Post reported. "[In] fact, neither was assigned a roommate during their four years there, unlike the other cadets." Two more enrolled the following year but lasted only two weeks in the hostile atmosphere. Of the first 21 African Americans appointed to the academy, Davenport and Tresville were only the sixth and seventh to graduate. The other 14 were discharged.

"Like one of their predecessors, Air Force Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr.," the obituary explains, "Col. Davenport and Tresville endured four years of 'silencing,' in which they were spoken to only for official business. No other cadets would sit by them, even during chapel services. At the end of the plebe year, when it was customary for upperclassmen to shake hands with rising cadets, no one took theirs."

Tresville was killed serving the country in World War II.

That sinking feeling

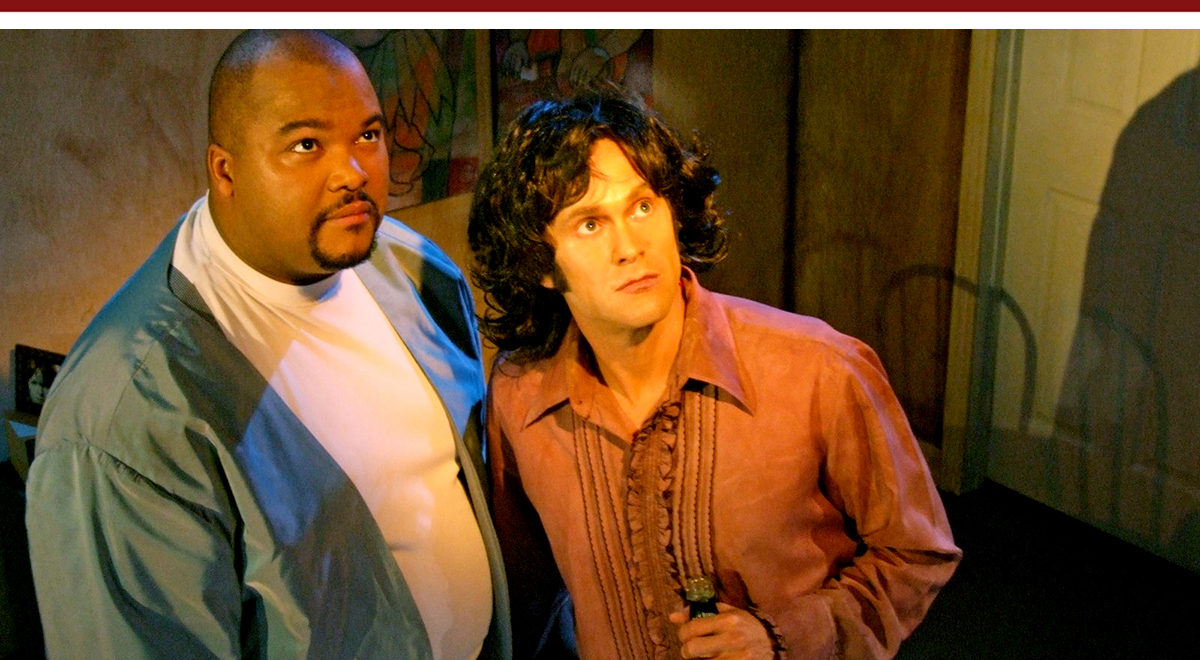

Morrison was dead: to begin with. There was no doubt whatever about that. Playwright Gary Flaxman, director Judy Rose and lead actor Damon Shalit, had done their best to roust him from his Paris tomb for Swimming to the Moon, a world premiere now through November 11 at Theatre Row's art/works Theatre. But The Doors' lyricist, lead singer and shamanistic pied piper, had apparently used his brooding, enigmatic and self-destructive persona to lead them to mount a drama with just those qualities.

A couple factors undermine their best intentions of blending rock star analysis, Freudian analysis, social analysis, and analysis of politics, sexuality, music, fame, poetry, eternity and the lure of the Shaman: The dialogue is limited to snarling, taunting, teasing and pontificating. Self-satisfied characters ponder ponderously. Heavy ego sits heavily to suppress dramatic lift.

Swimming to the Moon is set in Morrison's hotel room in Paris on the night he slipped into unconsciousness. Morrison (Shalit) takes to his living room bathtub after a few final slugs of whiskey and awakes in the next world. However, it's still his hotel room. But now seated in it is a large man in a silver suit. Al (Abner Genece) is a "transporter" sent to rub the dark poet's nose in his just-ended life. It will feel like an eternity for Morrison, who is challenged to examine his deeds, mistakes and contributions before choosing between two doors that lead to one eternity or another.

The dead star and the smug interrogator then engage in a cat and mouse game of fortune cookie one-liners dressed up as infinite wisdom. The opening scene takes awhile to get to the meat, as Morrison's know-it-all persona and Al's infinitely wise persona jockey for supremacy. Despite some level of omniscience, Al is an infuriatingly smug Buddha-type who bounces back questions rather than considering them. There's enough cuteness to slice and serve a la mode. At one point Morrison sidles up and rubs a cheeky come-on into Al's shoulder, telegraphing a mysterious ambi-sexuality that gets a kitten-paw rebuke: "You are a light in the darkness, aren't you?"

It's a gabfest with murky stakes. It may be Flaxman's goal to create a kind of '60s Don Juan in Hell, where a self-obsessed protagonist is made to defend his life. But the writing isn't exciting or deep enough to keep us interested. He can't seem to find enough points of interest for his tour of Morrison's mind, so Flaxman takes the story for a tour of some Big Issue '60s side shows: racism and civil unrest, politics and war, and to a lesser extent domestic violence. To guide us, he creates five after-lifers led by Jimi Hendrix and including character symbols named "The Fan," "Detroit Woman," "Senator" and "Soldier."

Though Shalit surely researched the Bejesus out of his role, it still smacks of album cover art. There's a head tilt, a slouch, a lazy speech that feel like stage affectations asked to stand in for a full personality. More effort seems to have been made in creating a physical and sonic Morrison than was went to giving him dramatic action and decent dialogue. However, give him credit for going for it. In his interactive Miami scene, and in those times where he has to pull Morrison's wail from the deepest recesses, Shalit doesn't hold back. God bless the working actor.

Hendrix (Russell Richardson), who is likely the most interesting character from that period, suffers the same fate. Richardson, without words worthy of that mystery man, is reduced to rerunning clips of the guitarist's swagger, arm gestures, etc. The scenes between Morrison and Hendrix leave the impression that these two, far from giants, were petty bickerers. Out of context of the times, the two goliaths that shook at least the pop-culture earth are reduced to plastic dinosaurs wiggled before a monster movie blue screen.

Perhaps because they aren't strapped into historical personae, or freighted with the import of "Senator" or "Soldier," the most engaging characters are the two women. The first time the play begins to breath is when Corryn Cummins' Fan appears. In her too-brief scene we finally get someone with the shell removed. Same for Sarah Scott Davis, who, in her short time on stage successfully covers a lot of ground, and helps Hendrix revisit some of what the '60s were about for black Americans.

It's impossible to recreate one era's zeitgeist for another. Historians do the best they can by assembling as many details and anecdotes to rebuild the world as it was. The dramatist on the other hand, honors the facts with interpretations that, in his or her opinion, get to the heart of what was happening. Sadly, Gary Flaxman's Swimming to the Moon, isn't very useful history or compelling drama. A show that would seem to call out for an amazing sound design gets only a couple cues, including Darren Glover's respectable bit of "Foxy Lady's" chomping intro.

The '60s are dead, to end with. There seems to be no doubt whatever about that.

top of page

SWIMMING TO THE MOON

by GARY FLAXMAN

directed by JUDY ROSE

ART | WORKS THEATRE

September 15-October 28, 2007

Opened 9/19, rev'd 9/27

CAST Jake Bern, Corryn Cummins, Sarah Scott Davis, Abner Genece, Russell Richardson, Damon Shalit, Steven Shaw

PRODUCTION Theresa Shook, set; Peter Lovello, costumes; Michael Mahlum, lights; Damien Virgil, wigs; Katt Masterson, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Abner Genece and Damon Shalit

INSET: Shalit and Corryn Cummins

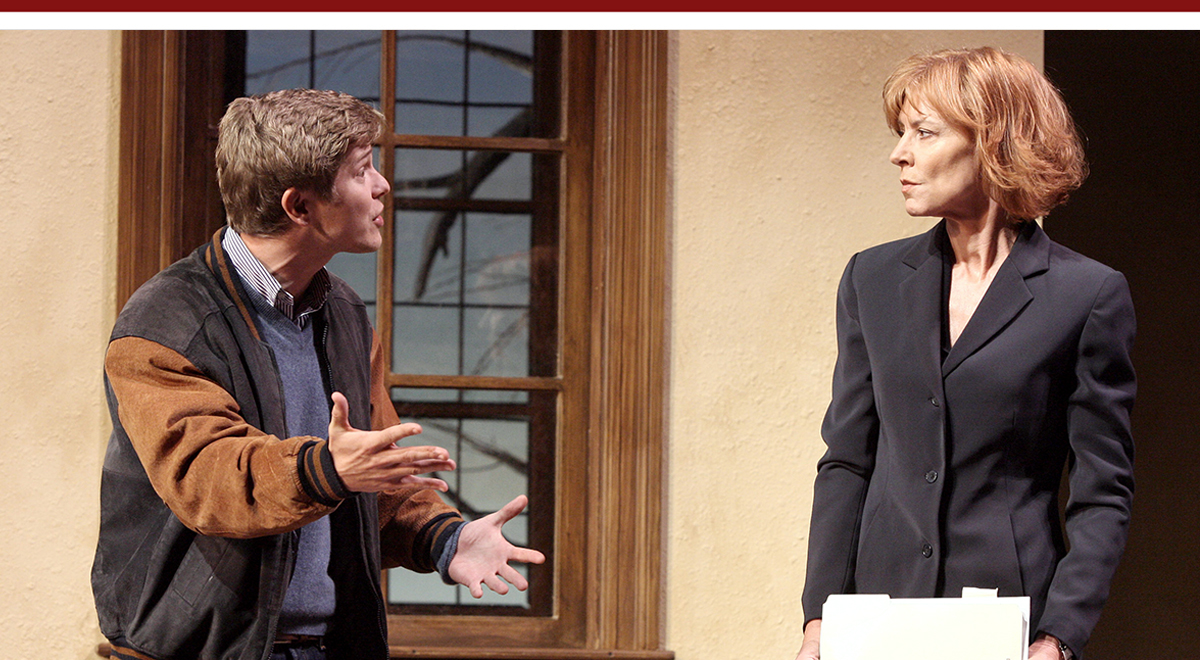

Waved home

In August 2006, seven months after Wendy Wasserstein died at age 55, the Old Globe gave the playwright a respectful tribute in its successful revival of The Sisters Rosensweig. This year, the Geffen Playhouse has mounted Wasserstein's own farewell with Maria Mileaf's staging of the West Coast premiere of Third. There's some indication that the lymphoma that cut down the writer cut short her rewrites. But Third, a serious drama that turns on an almost prankish bit of rug pulling, stands firmly as the loving and powerful statement with which she wished to leave the world.

The long shadow of King Lear falls gracefully across this story: From the tragic flaws of its central character, Professor Laurie Jameson (Christine Lahti), to the use of the text as a battleground for play analysis, to the image of its title character in Jameson's mad, wild-haired and storm-tossed father, Jack (M. Emmet Walsh).

While Third is entertaining and instructive on its own, it gains greater depth as the final reflections of one of the era's most important writers. We feel a "what-Iíve-learned" strength bending the play's arc, from its schticky, dismissive opening monologue to the open-minded acceptance of things that pervades its final moments. Meanwhile, she keeps her chosen field central to the play's events, celebrating and promoting the value and fun of freely exploring theatrical text, then extending that freedom of choice to religion, lifestyle, education, family bonding and politics.

Wasserstein has a lifetime of ground for Jameson to cover in her two acts. To do this, Lahti must create a character who has made a positive impact on students for 25 years despite huge blind spots to her own prejudice, and a juvenile habit of taunting others by flaunting her credentials. Likely, with a little more time and energy, Wasserstein would have sculpted more contour into Jameson. It's hard to see how Mileaf and Lahti could have gotten more out of her as written.

However, while her obvious shallowness distances us during first act scenes with her daughter Emily (Sarah Drew), her colleague (Jayne Brook), her father, her shrink, and a troublesome student, it does not damage the story. Instead, we soon are caught up in watching as she gradually, mostly through loss, gains an understanding of real liberty and equality.

Jameson is teaching a re-examination of King Lear in the light of modern psychology. In her view, Regan and Goneril, Lear's self-interested older daughters, are more deserving of their thirds of his estate. Cordelia, Jameson insists, is just a simp subjugating herself to the "girlification" of women in order to get her third. In her backhanded way, as Jameson holds Shakespeare's mirror up, she reflects on her own nature. And long before she does, we see both sides: the mind of a prickly independent who drives people away (her offstage husband keeps finding new obsessions to distance himself from her), and the large heart of one who selflessly takes on the thankless job of accompanying a parent through dementia.

Jameson's "I've seen it all" posturing is further stiffened when she meets a student whose name signals old school privilege. Woodson Bull III (Matt Czuchry), whose nickname is the play's title, is an athlete who skips important classes for wrestling meets. He holds views that are right of center, though he claims independence, and that smack too much of Republican beliefs for Jameson. Czuchry is impressive in what his bio indicates is a major stage debut (though he could lose about half of his act one gesturing).

In a predictable plot move that will rankle cranky critics, Third hands in a paper that is so far beyond good it's publishable. Jameson is convinced he has cheated. This does not only confirm her prejudices against him, but validates her anger at the decades-long "our ends justify your means" through-line of Republican administrations. Proving that he plagiarized becomes a crusade to expose this telling example of the double-standards inherent in American conservatism.

The production is beautifully simple, and locations change quickly and thoroughly, from the stone campus buildings to a contemporary home and townie bar. Vince Mountain designed the set; Alex Jaeger the costumes; David Lander the lights; and Michael Roth composed the music. (Though there are some oldies required by the script, including a tune by Laura Nyro who Wasserstein reminds us was also taken early.)

Mileaf moves the show effectively through its rougher early scenes to get to where higher stakes are revealed and we get traction through to curtain. She navigates these latter sections particularly well. A lovely scene between Emily and Third becomes the centerpiece Wasserstein could only have dreamed of, where two young people, somehow neurosis-free survivors of their parents' generation, give real signs of hope. Then, with equal care, Mileaf sets up the heart-breaking final scene between Jameson and her father. Here Wasserstein takes her Lear, infantilizes him with dementia, then briefly gives him back his glory through a slow dance with his daughter that is a lasting gesture of his disappearing generation's romantic signature.

And, finally, just as her character is undone, and the social barbs she used to chum the audience are undermined, one character makes passing reference to the third segment of one's life, which should begin around the mid- 50s. In bittersweet acknowledgment, Wasserstein allows that though she will not live her third, she will write one, and use it to wish her audiences well, remind them to do good, and urge them, for goodness sake, to enjoy it.

top of page

THIRD

by WENDY WASSERSTEIN

directed by MARIA MILEAF

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 11-October 28, 2007

Opened 9/19, rev. 9/22m

CAST Jayne Brook, Matt Czuchry, Sarah Drew, Christine Lahti, M. Emmet Walsh

PRODUCTION ince Mountain, set; Alex Jaeger, costumes; David Lander, lights; Michael Roth, composer; Dana Victoria Anderson/Christopher Paul, stage management

HISTORY West Coast Premiere