IMAGINING BECKETT

Composer Michael Roth's 30-year journey with Samuel Beckett's Imagination Dead Imagine

More than 35 years ago, a 21-year-old composer living with his parents in Long Island had the chutzpah to imagine a collaboration with one of the most revolutionary figures in the history of English-speaking theater. And, as sometimes happens to determined dreamers, a path suddenly appeared to make it happen: Michael Roth was corresponding with Samuel Beckett.

What took place over the following three-and-a-half decades is the subject of the following exchange – a combination of phone interview and narrative from existing material Roth wrote for the 2017 world premiere of his Imagination Dead Imagine in San Diego, its subsequent Los Angeles performance at the Broad, and now for its May 5 and 6 performances at a new space in Pasadena, California.

Roth's Imagination is a unique theater-and-music event inspired by and incorporating text by Beckett. The Pasadena performance, at The Hen House is prelude to what will be the European Premiere September 13-16 at the Beckett & Technology Conference in Prague.

Performing the music here and there is the Quartet Nouveau, a Southern California-based string quartet comprised of Elizabeth Brown, Missy Lukin, Batya MacAdam-Somer, and Annabelle Terbetski.

Ticket sales and tax-deductible support the costs of getting the Quartet to Prague. Click here to purchase tickets or support with a donation.

THEATERTIMES First, congratulations, Michael, on creating this piece and getting such a prestigious international showcase for it in September. To begin, can you describe Imagination Dead Imagine?

MICHAEL ROTH Ultimately Imagination Dead Imagine is a music/theater piece – even an opera – for String Quartet and recorded voices in which the string quartet is the protagonist, listening and responding to what they hear. It's as if a string quartet walks into a room - and approaches a laptop that seems to have been placed on a table for them. Each player in turn, one at a time, presses the space bar and hears the recorded line, "No trace anywhere of life." Each member, as they hear the line, puts on an earpiece (to hear the click track) – and each presses the space bar as often as needed to make sure they hear everything they need to hear (the click and the voices) in order to proceed. This is repeated as necessary until everyone is ready. Each player picks up a manuscript, a piece of music that is their part for the piece, and places it on a stand. Finally, a player presses the space bar one last time, and the piece continues on. The quartet hears the voices as Beckett’s text and "plays" their response.

THEATERTIMES What was the genesis of this unusual piece?

MICHAEL ROTH Well … Imagination Dead Imagine is a text, a novella that Samuel Beckett wrote in 1965 – originally in French, entitled Imagination Morte Imaginez. Years ago, when I was 21 and had just graduated from the University of Michigan, I met in London with the drama critic Martin Esslin, author of The Theatre Of The Absurd, and coincidentally my teacher’s teacher. We had in fact met several times before. Over coffee and Kit-Kat bars, I told him that I wanted to "set some Beckett someday."

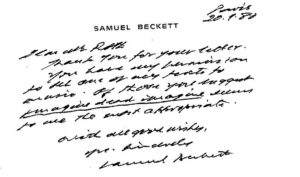

He said, "Well, why don’t you just write to him?" A reasonable, albeit obvious, suggestion. At that time I was living with my parents on Long Island, and sometime after I got home, I wrote to Mr. Beckett c/o his publisher in Paris. In what I’m sure was an overly fawning letter, I told him of my meeting with Esslin and my desire to set something of his, listing several of his texts as suggestions. Much to my shock he wrote back, in a letter dated January 20, 1980, and gave me permission to set one of the texts I had suggested. Imagination Dead Imagine, he wrote, "seemed the most appropriate."

THEATERTIMES Do you have that correspondence?

MICHAEL ROTH I no longer have my letters to him, but his letters are framed on my wall. [One is shown at right.]

MICHAEL ROTH I no longer have my letters to him, but his letters are framed on my wall. [One is shown at right.]

Arriving at a solution took some time, and setting a text can have several meanings. Doing my best to create a little order, like Clov in Endgame and perhaps many others, I thought about a number of ways to approach the text. Imagination Dead Imagine is a great, but, musically speaking, at more than 1,100 words, it’s a fairly long prose piece. Though I gave it a lot of thought, the idea of it actually being sung by somebody or a group of some kind seemed counter-intuitive. The text was not poetic and not really singable. I thought about this tricky problem for years, knowing there must be some solution eventually.

Over the following 25 to 30 years, technologies emerged that made many previously unimaginable things not only possible but almost convenient. I was able to record a handful of people reading the text as much as four times each. Then, in Pro Tools, I mixed and lined up all of the voices word-by-word and syllable-by-syllable to create an interesting choir. This way, the music doesn’t set the text, so to speak, but the text creates a musical landscape for music to live on and even, importantly, become an antagonist.

While in rehearsals for The Tempest with Christopher Plummer at Canada's Stratford Festival, I recorded friends in the company: Geraint Wyn Davies, Dion Johnstone, Seana McKenna, and Lucy Peacock. I eventually also recorded actor-director Marco Barricelli, a UCSD faculty member and former artistic director of Shakespeare Santa Cruz, the South African actress Jessica Jean Erwin , and Canadian-American actor Robert Joy.

THEATERTIMES When did the actual composing begin?

ROTH Once I'd imported the recorded voices into pro tools, and lined them up with a click track, I then composed the Quartet. I was able to imagine a scenario wherein the Quartet was hearing the text for the first time and living in it, responding to it, agreeing with it, protesting against it, and so on. Like Krapp’s Last Tape or Eh Joe, but instead of an actor responding to recorded voices we see a string quartet as the protagonist. And through them we, the audience, are listening, watching and living in Beckett’s text.

The audience witnesses the Quartet hearing and instructed by recorded voices and reacting as they see fit - sometimes being ok with it, fairly often not. At the end of the piece, when the voices are done talking – and the click track the musicians have been relying on to play with the voices has disappeared, they are left on their own - now they play music because, seemingly, if they don’t play, perhaps - likely - they don’t exist. And, accordingly, it’s my hope that in the end, when the voices and click track gone, that the isolation and, for want of a better word, loneliness of the string quartet is felt rather strongly, akin to how an actor might feel (and how we might feel observing the actor - or Didi or Gogo, et al, as the case may be) while performing in a Beckett play, or how we might feel after experiencing Beckett’s work in any other context.

The music is, for want of a better term, molto espressivo – that is to say, very expressive, not dry or cold - members of the Quartet should experience the piece emotionally as well as intellectually, and not be afraid of that. Also, if possible, the Quartet stand - not sit in a traditional Quartet position, facing each other, the violinist and cellist on the outside – rather they should all face out to some extent so we see them all rather evenly, we see them respond to what’s happening to them. In the end, when they are forced to play together with no click, the first violinist brings them in and they play free from an “authoritarian” click track for the first time.

Throughout my career I’ve had equivalent interests in contemporary music techniques, contemporary theatrical dramaturgy, modern pop music and songs, and new musical theatre. More often than not, these varied interests lead to a certain amount of tension, even conflict from colleagues and collaborators from these various fields. New music artists have at times been naïve of contemporary dramaturgical thinking, just as new theatre artists can be naïve of what new music artists have been concerned with theoretically and contextually for the past century. Aesthetically, this project allows me to continue what I hope is my innovative work as a contemporary music artist working in theater, bringing new music and new digital sound techniques to the use of live music and recorded elements in a theater piece.