THE PLAYWRIGHT ESSAYIST

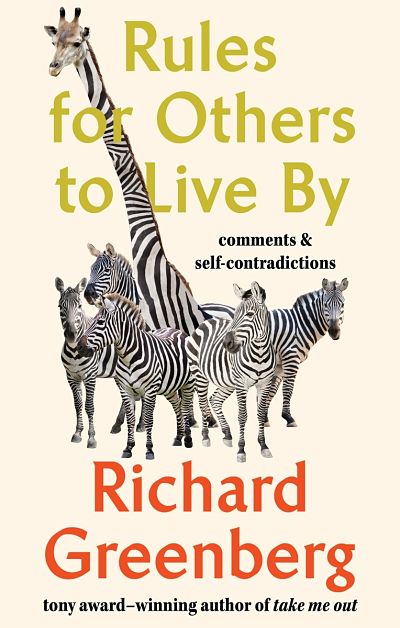

Playwright Richard Greenberg talks about his book of essays,

Rules for Others to Live By.

by MADELINE KING PORTER

Playwright Richard Greenberg doesn’t go out a lot. Some people who know this about him but don’t know him, are quick to apply the label "hermit." Greenberg is not a hermit. He just doesn’t go out a lot. Consider this. He lives in a sleek two-level condo with an enviable view — in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. Floor-to-ceiling shelves fill a long wall of the living room and overflow with books. The ample kitchen and dining area were meant to be cooked in and dined in and are, with friends, frequently.

This airy, light-filled upstairs space is also where Greenberg works. Just imagine the thoughts that have originated here. Lucky for us, many of them found their way to the stage. And now, some of the most succulent are contained in a book of essays with a title that is unabashedly Greenbergian: Rules for Others to Live By, one of which, early on, addresses the hermit issue. Because I find the dialogue packed into his trove of plays so readable, a book of essays seemed like a logical transition. But I wondered how it had come about and why, so I asked him that – and a few other things – on a recent trip to New York.

Your bios usually lead with “Tony Award-winning playwright and Pulitzer Prize finalist.” So the obvious question is Why essays and why now?

It was someone else’s idea, actually. I resisted at first. When I started, it felt very natural. This is because all I ever do, really, is write essays; walking around, taking in information, forming sentences in response, then organizing the sentences into arguments. This is also known as "talking to yourself." I talk to myself constantly. It’s amazing I haven’t been hatched-up.

Once you decided on this form, how did a writing day differ from a day of playwriting?

The day didn’t differ at all, really. It was chaotic, enthusiastic, — the same. What differed was the degree of completion that was possible. A play— even a finished play-- is just the text for an event. With an essay, if it works on the page, it works. That’s very satisfying. Also, the form is completely different and has an almost antithetical impulse. For me a play starts with a character, an image, a scrap of dialogue, a situation, a memory— never a theory, never an idea that I’m trying to clothe in drama. It discovers its point as it goes along. An essay can begin as an argument you’ve already finished in your mind. Very pleasant, very didactic.

In one essay, you explain that, sometimes, lying awake in bed, "an idea just drops in." Otherwise, and ordinarily, do you keep a journal, and do you have a writing schedule?

No, and no.

Some of the essays are just pithy thoughts in a sentence or two that make the reader chuckle. How do you determine when to stop and walk away, chuckling yourself?

I’m not a literary minimalist but I very much admire writers who are— I love the flash fiction of Lydia Davis, for example— there’s so much power in all that negative space on the page. Why work in a new form if you’re not going to try a few unfamiliar things? And I’m attracted to the possibility of supplying just enough data. I love leaving things out— I think the experience of not having all the information is primal. By the way, I think I hate the word ‘chuckle.'

Duly noted. Of the longer pieces, "Dinner," is my favorite. It’s conversational, in such a smart way. A lot of writers pride themselves on "naturalistic" dialogue, while suggesting that dialogue in plays like yours (and, say, Noel Coward’s) and now, essays like "Dinner," isn’t the way people really talk. Obviously they haven’t sat at your dinner table. Do you write for a specific audience (i.e., smart and sophisticated) or just for yourself, knowing the smart and sophisticated will come?

It’s true, I know a lot of very smart people who are not shy about wielding the language that’s available to them and I’ve never been especially attracted to unvarnished naturalism. At the same time, I have absolutely no desire to be Noel Coward. He was fantastic, but he was an English guy who wrote his first play almost a hundred years ago. There’s no point to a contemporary American one of those. Anyway, I’m not aiming for style but energy. I write to keep myself interested in the hope that there are others who are interested in the same things I am.

Maeve Brennan, for those who don’t know, is a New Yorker writer from a bygone era. She’s clearly a favorite of yours. One of the book’s loveliest sentences is a tribute to her. (The reader will know it when it comes.) How is Brennan’s influence manifested in your work—if it is?

Oh, she’s all over the essays. At this point, I have no idea who influenced me as a playwright, but reading Maeve’s essays was like— well, I don’t know what it was like. I didn’t feel I’d found a home. I didn’t feel she understood me. I just knew that The Long-Winded Lady was a book I was going to read over and over. And, inevitably with that, there was some effort to analyze and later, when I started working in her form, emulation. I have no idea what sentence you’re referring to.

The reader will. It's on page 212.

I laughed aloud at "Selling Out" which asks the question, "How hard could it be to write a Nicholas Sparks novel?" and then answers it by quoting an actual Sparks first line: "The summer I turned seventeen, everything changed forever." Whoops. Bemoaning the loss of money by not selling out, you explain your failure with an observation by Nora Ephron—writers like Sparks and Jacqueline Susann were doing the best they could. Truthfully, though; haven’t you been tempted to give selling out another try?

Find me a buyer.

I ask this because, as an old romance writer, I once attempted the opposite, i.e., writing a "literary" novel, and got half way through before realizing it wasn’t going to happen. Romance writing is the best I can do. However, there are good writers out there who write (bad) bestsellers under pseudonyms. You have the perfect first line: “After that winter, I would never be the same again.” Think how much fun it would be to write a second and third sentence! Will you do me a favor and just finish the paragraph?

Sadly, I can’t. If I could, I would be answering these questions from my villa on Lake Como.

While the opening lines of a Sparks novel might cause the reader to throw the book across the room, you have some irresistible ones. How about, "Emma got married because I cancelled brunch" or,"Eight years ago, I was congratulated for not wearing a certain coat." Not to mention, "In Chelsea, we get very little weather." And some of the titles; for instance, "My Friend, the Murderer Manqué" are equally enticing. In structuring essays, do the opening lines/titles come first or do you come up with them later as teases—and do you smile a little when you realize that it will be impossible for the reader to stop reading at the first period?

There is no method and no predictability. Some start with the first sentence and are written straight through. Some are written in random spasms and organized later. As I’ve said, I try to keep myself interested.

Speaking of the Murderer Manqué, a totally captivating character, who reminds me—once he puts the subject of murder aside—of you, especially because he “considers conversation an event.” You’re equivocal in the pre-introduction (“Apology to Oprah”), saying among other noteworthy contradictions, that “some names have been changed” and “a few of the people I describe do not, in the strictest sense of the word, exist.” I wonder if a few of their jaw-droppingly funny lines were, if not the author’s own, edited/expanded by him?

He consulted.

Occasionally, your writing is self-deprecating, in a very funny way. This is patently true in the book’s first essay, “Wisdom,” in which you declare yourself a wise man because “…people have told me so, among them several who consider my intelligence average and my talent meh.” Who isn’t going to want to read on after that, especially when, on the next page, you talk about being a good playwriting teacher because you’ve faltered at it in so many ways, “Ah, yes, that mistake! Remember it well. Made it myself in the hardscrabble winter of eighty-six.” I’m not sure what my question is here. Maybe I just wanted to write down that line. Or just ask you to comment?

It’s a very nice moment when you start to feel comfortable with your failings. Once that happens, it’s a short step to yelling them from the treetops.

In one of the pieces, you slam South Pacific, hilariously. But I know you’re a fan of (other) musicals. What are some of your favorite shows?

I can’t account for it but I saw Light in the Piazza 19 times. It’s a wonderful, wonderful show but I haven’t seen any of my own plays 19 times.

Now that we’re on the subject of favorites, Who are some novelists, poets, playwrights, biographers (am I leaving out categories?) you admire?

Could I have a Sarah Palin moment and lie, "Oh, all of them?"

What are you currently working on/planning? Brennan is a favorite essayist; now you’ve written a book of essays. I know you’re a Philip Roth fan. Is a novel next? Or is there one already, hidden away?

I’m working on a secret summer project now, not a play.

Why do you think New York City is the setting for work by so many great American writers from Henry James to Joseph Mitchell to Philip Roth and beyond? And can you imagine setting Rules for Others to Live By anywhere else, like, say, Philadelphia?

Oh Madeline, have you been to New York City? And no, I could not have set it in Philadelphia. East Lansing, maybe.