MAY 2007

Click title to jump to review

THE CONSTANT WIFE by W. Somerset Maugham | Pasadena Playhouse

FAT PIG by Neil LaBute | Geffen Playhouse

MAN OF LA MANCHA by Dale Wasserman, Mitch Leigh, Joe Darian | A Noise Within

PACIFIC PLAYWRIGHTS PROJECT by Various | South Coast Repertory

YELLOW FACE by David Henry Hwang | Mark Taper Forum

'Constant' returns

After a year, W. Somerset Maugham's enduring Constant Wife is back on stage in Southern California. As an Old Globe staging suggested last year, Maugham's literary powers were in full-enough flower in 1926 that this message comedy rings true 80 years later. What might have been dismissed when it premiered as a prescription for infidelity can now be seen as a primer on how best to insure a shared marriage yoke.

A script this well crafted should work with any cast capable of staying out of the story's way. However, the cast director Art Manke has assembled at the Pasadena Playhouse through June 10 makes this an especially good night for Mr. Maugham. Only an imposing and oddly garish set, which will be addressed, undressed and redressed later, earns the production any demerits.

Chief among the acting assets is Megan Gallagher as Constance, the titular spouse. Before Ms. Gallagher's first entrance, Mr. Maugham prepares us for a pitiable woman who is unaware that her husband is cheating with her best friend. From her gait to her gaze Ms. Gallagher quickly dispels such notions and establishes Constance as a study in steadiness – a woman unlikely to be victimized. Ethel Barrymore created this character on Broadway and enjoyed a 300-performance run. Mr. Maugham is quoted as saying her performance was the best he had seen in any play he had written. She set the bar high, but Ms. Gallagher serves the tradition well. Here, Constance looks to be comfortable with early middle age, dressing and coiffing without need to deceive, yet maintaining a beauty that will reward the constancy of still-smitten Bernard Kersal (Kaleo Griffith), who last saw her 15 years before, following her rejection of his marriage proposal.

Mr. Maugham gives mixed signals as to whether or not Constance is able to leave her husband John (Stephen Caffrey), or even wants to. When another friend (Ann Marie Lee) offers the chance for her to get out of the house and enter business, she confesses she is happy at home. Is it a case of the emptiness she knows being preferable to the one she doesn't? Ms. Gallagher's performance seems to project a woman who has lived a life of her choosing.

She chose John over Bernard because he seemed the less devoted. After an initial five years of passionate love, theirs eased into the love between devoted friends. When John's affair with Marie Louise (Libby West) is disclosed, Constance reveals she knew about it but saw no percentage in exposing it and risking divorce. "I never understood why a woman should give up her home, a considerable part of her income and having a man around the house to take care of all the tiresome chores."

But the extramarital outing occurs in the presence of the still-obsessed Kersal – who Mr. Griffith gives a winning blend of matinee idol looks and mid-level intelligence. In her mind, John's philandering and the public humiliation it brought has earned Constance a Free Affair Coupon. With the debonair Kersal at the ready she sets in motion a plan to gain financial equality, sample passion one last time, and afford John the bitter taste of the cuckold's medicine.

A large gilded birdcage, with its own special, supports the production's metaphor of constant confinement. So, too, does the floor-to-ceiling grid of upstage windows. Long diaphanous drapes of focus-yanking blue laze against those windows, and some ugly, pedestal-borne sculpture, further force the set and actors towards the apron. The company's downstage confinement will be explained in the play's final scene. Until then, our attention is drawn to the drapes, a garish chandelier, and this odd wall of sitting room windows. (It's especially ironic that when a set design is actually attributed to a character on stage – and a character, Constance, whose independence will be dependent on her decorating – it looks so tacky.)

Of the rest of the cast, Mr. Caffrey, a favorite for his recent turn in SCR's Bach at Leipzig, creates a blustery Dr. John, a bit of a blowhard beneath a constantly knitted brow. West earns her laughs as Constance's conscienceless pal. Monette Magrath keeps younger sister Martha animated, if perhaps too young. John-David Keller, Andrew Borba, and Carolyn Seymour round out the cast.

In a beautiful directorial coda that shows Constance in Italy (and explains the windows and the crowded stage), Mr. Manke sets Constance free. It's a fine, hard-won stage moment suggesting that freedom is its own reward. But, the fact that she is heading back into a different kind of marriage seems to make this lovely flourish a bit beside the point. The triumph to relish is not John's defeat, but in forcing him to accept her as his true equal. That final face off, which normally signals lights out, should be just desserts enough.

top of page

THE CONSTANT WIFE

by W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM

directed by ART MANKE

PASADENA PLAYHOUSE

May 4-June 10, 2007

(opened May 12, rev'D 5/12)

CAST Andrew Borba, Stephen Caffrey, Megan Gallagher, Kaleo Griffith, John-David Keller, Ann Marie Lee, Monette Magrath, Carolyn Seymour, Libby West

PRODUCTION Angela Balogh Calin, sets/costumes; Peter Maradudin, lights; Steven Cahill, sound; Lea Chazin/Hethyr Verhoef, stage management

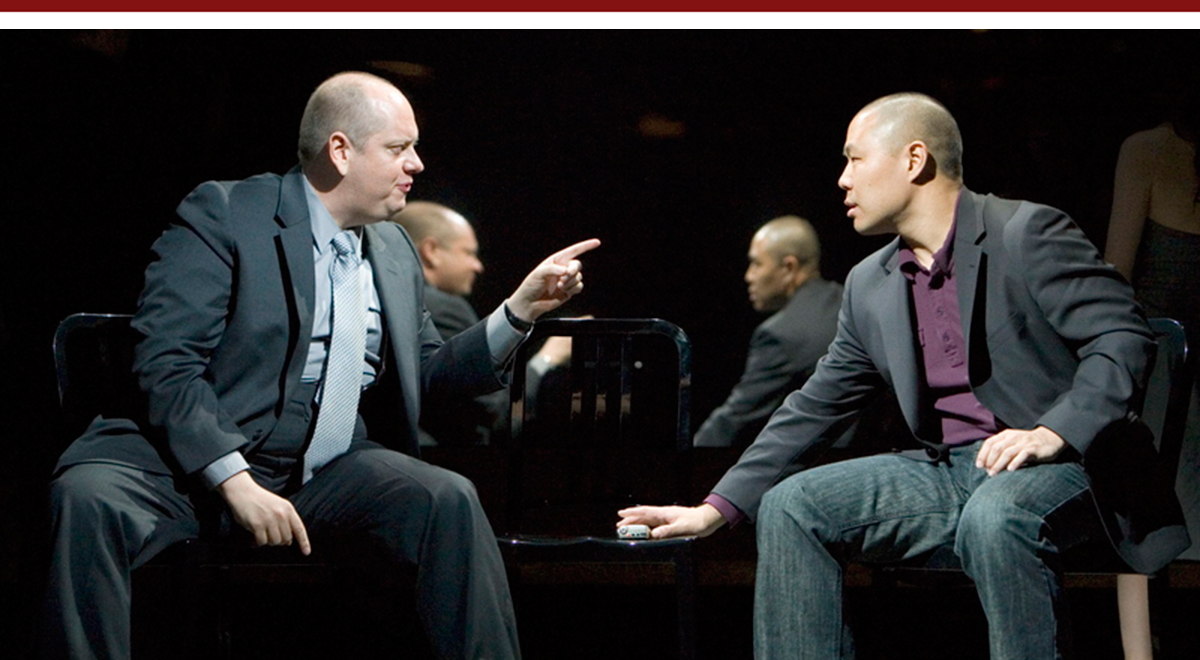

Megan Gallagher, Kaleo Griffith

Craig Schwartz

Slim to none

The need to overcome low self-image and be thick-skinned enough to overlook demeaning opinions of others is at the heart of Neil LaBute's Fat Pig, now in its West Coast premiere (through June 10) at the Geffen's Audrey Skirball Kenis Theater in Los Angeles. The title suggests a much nastier piece of work than this 90-minute, intermission-less script from the smart and fearless author of such plays as The Shape of Things, Autobahn (reviewed here) and Bash and the films In the Company of Men, Nurse Betty and Your Friends and Neighbors.

Instead, Fat Pig seems to settle in more like a contemporary television dramedy with a single story line and stock characters from hit shows. There's a further dimension of familiarity in the attracted opposites at its core, who give it a Disney fable quality: like a reverse anthropomorphizing of incompatible cartoon animals out to set an example for the rest of the forest. Yet the kind of menace that LaBute previously employed in his unsettling comedies shadows this story beneath the surface, waiting until the final curtain to rise up and make us pay for our laughs.

Obesity in this country is, of course, no joke. There's no question that it is dangerous to be greatly overweight and/or the victim of compulsive overeating, yet LaBute manages to have his cake and eat it, too. His characters divide between master purveyors of fat jokes and heart-breaking targets of them. We are early on given permission to laugh when the character referenced by the mean-spirited title reveals that she is quite comfortable in her own skin. Fat Pig is in fact not about how or why one becomes obese, but about the more universal issue of how groups treat the "other," and what happens when people try to see past those definitions.

LaBute and director Jo Bonney push the question of how audience members will react when the title character first appears. They immediately turn the tables by stationing Helen (Kirsten Vangsness) on stage for pre-show. Standing at a high table, eating what looks to be a starchy lunch from a cafeteria tray, she occasionally looks up from Walter Isaacson's hefty new Einstein biography (she's a librarian and voracious reader) and looks around the lunchroom at the audience without making eye contact. Accustomed to eating alone, she has spread her gear over the two-person tabletop, which forces Tom (Scott Wolf) to make eye contact and conversation with her when he needs a spot.

Tom Sullivan (the name also belongs to a real-life blind entertainer) discovers over the course of a quippy chat that Helen also tips the scale in the personality department. The twentysomething Tom, at sixes and sevens regarding his life direction after another lack-luster relationship, ventures a cautious request to see Helen sometime.

His parents might have said about ordering off the menu, "Donít take a bite of something you can't finish" but Tom appears to be blind to Helen's weight. He wants to test his mettle and probe for a deeper connection with someone. He may also, given his boyish Michael J. Fox irresistibility, subconsciously believe that even a brief affair with a hunk would be a net gain for Helen. However, foreseeing the ridicule a relationship with her will heap upon him from friends and co-workers, he quickly closets their get-togethers.

Bonney keeps the depth of the inner turmoil in these two from surfacing for most of the play. It's a measured strategy to provide greater impact later on, but it does make the bulk of the play seem lighter than it otherwise might. LaBute has kept his stage tidy with only two additional characters, both from Tom's world.

Without a friend of her own, Helen can't let her hair down and show the mix of euphoria and dread that accompany suddenly becoming the object of desire of a truly cute guy. We only glimpse how she's feeling through her carefully monitored interaction with Tom, where she must keep the lid on her feelings so as not to freak him out. Structurally, therefore, Vangsness is prohibited from making this show her own, but she gives us glimpses into her true feelings as much as she can, and sounds the plea we should all heed: "Just be honest with me."

Instead, Tom and Helen's relationship is reflected in the cool, cruel world of Tom's office, where the people are incapable of looking unattractive, and of looking at the "unattractive" with anything but contempt or pity. Ironically, they appear incapable of engaging in healthy relationships of their own. Jeannie (Andrea Anders), a sexy 28-year-old from the accounting department who has been dating Tom, has to wring from him the fact that he isn't interested anymore.

Wisecracking co-worker Drew Carter (Chris Pine) is given a breadbasket of assorted roles: confidante, nemesis, blockhead, and clear-eyed seer (with his own shameful story of an obese loved one). To his credit, Pine keeps all these facets within his acting wheelhouse and makes this grab-bag character feel real. It's also a very entertaining performance.

The jilted Jeannie also gives us the embodiment of that funny-painful experience of knowing you're in a go-nowhere relationship, but becoming incensed when the other person pulls the plug. The real-life odds against the most highly compatible Helen being chosen over even a high-maintenance Jeannie are slim to none.

Still, in the world of literature, anything is possible. At one point, thereís a slight evocation that, like Huck, Tom has escaped the real world and now floats in harmony with the person he freed, and who has freed him in return. Twain's raft ride through race relations will have a happier ending. If Tom tosses Helen overboard, she likely will not make it back to the healthy spot she had reached in her life. Instead, she could sink under the weight of a rejection she had allowed herself to hope wasn't inevitable.

Bonney has an excellent design team with costumes by Christina Haatainen Jones, lights by Lap-Chi Chu, a sleek and versatile multi-location unit set by Louisa Thompson, and a tough, engaging soundtrack by Colbert S. Davis IV.

This review ran originally on Blogcritics.com and was edited by Diana Hartman.

top of page

FAT PIG

by NEIL LABUTE

directed by JO BONNEY

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

May 5-June 10, 2007

(Opened May 11, rev. 5/10)

CAST Andrea Anders, Chris Pine, Scott Wolf, Kirsten Vangsness

PRODUCTION Louisa Thompson, set; Tina Haatainen Jones, costumes; Lap-Chi Chu, lights; Colbert S. Davis IV, sound; Frankie Ocasio, stage management

Kirsten Vangsness and Scott Wolf

Michael Lamont

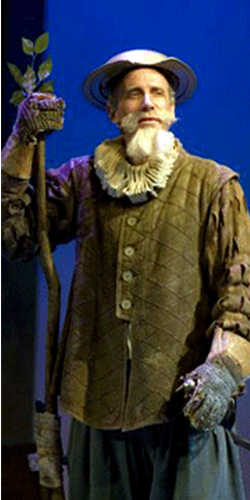

Knight errand

Don Quixote de la Mancha, the title character of Cervantes’ 17th Century novel, was born for a life in the theater. His onion-layered identity – a commoner who cannot separate reality from literature, in a fabricated tale validated by a made up historian – is tailor made for stage actors who simultaneously are person and character.

It wasn't until the 1960s, however, when Dale Wasserman, with the help of composer Mitch Leigh and lyricist Joe Darion, converted his teleplay version of the story to stage musical that the essence of the Quixote story found an equally fantastic theatrical motif. That musical, The Man of La Mancha, is currently getting a good showing at A Noise Within in Glendale, California, now in an extended repertory schedule through June 10.

In the novel, Cervantes invents an expert to verify a story he discovered in Arabia. This Arabian tale involves a minor landowner so stuffed with story that he goes out into the world in a cloud of chivalrous delusion. He is on a mission to cure the world of its ills and earn the love of a special woman. For his stage version, Wasserman puts the author Cervantes at the mouth of the story, tossed with his Quixote manuscript into a prison. (Cervantes in fact had spent time under arrest.) Cervantes then acts out sections of the novel for the inmates, using them to portray some of the characters.

A Noise Within has a ready character of its own to lend to the chain of Quixote personalities. Geoff Elliott, who co-founded A Noise Within with his wife Julia Rodriguez, who directs La Mancha, is also the company’s most frequent leading man. As a creative force behind the theater who gallantly takes on performance duties to help keep the wolf from the door, he is a kind of clear-headed Quixote who has fought for his dream across a deriding countryside. Elliott’s acting style is well suited to Quixote’s take on the world. It is an affect perfect for the detached would-be knight. When he drops it, to play Cervantes, it really distinguishes the two.

As Sancho Panza, Quixote’s corpulent corporal, Alan Blumenfeld makes another outstanding contribution to A Noise Within. His title turn in Ubu Roi last year was delightfully over the top, and here he occasionally pushes Panza's size beyond its design. However, it’s never off-putting, and always appreciated, especially against an ensemble that feels a little drab outside the central core.

The third element of that core is the country girl Alonza whom Quixote's imagination transforms to the ravishing Dulcinea. She is played here by Nadia Ahern, who keeps the character grounded in the real world as counterpoint to Elliott's Quixote. She also delivers the songs, as do Elliott and Blumenfeld, with gusto and conviction. Though the remainder of the ensemble is less interesting, Elliott, Blumenfeld and Ahern keep this focused. And, the physical production of Melissa Ficociello’s set, Soojin Lee’s costumes and Ken Booth’s lights fit both story and theater space perfectly.

As he always does, David O, as musical director and performance pianist, provides a solid musical foundation for the show.

top of page

THE MAN

OF LA MANCHA

by DALE WASSERMAN

music by MITCH LEIGH

lyrics by JOE DARIAN

revised orchestrations and

musical direction by DAVID O

directed by JULIA RODRIGUEZ-ELLIOTT

A NOISE WITHIN

Through June 10

CAST Geoff Elliott, Alan Blumenfeld, Nadia Ahern, Steve Weingartner, Steve Rockwell, Deb Snyder, Gregory Franklin, Meaghan Boeing, Alison Elliott, Erich Schroeder, Scott Asti, Radick Cembrzynski, Nora Frankovich, Susan Jewell, Brandon Lim, Andy Steadman

MUSICIANS: David O, piano; Kevin Tiernan, guitar

PRODUCTION Melissa Ficociello, set; Soojin Lee, costumes; Ken Booth, lights; Ken Merckx, fights; Kate Barrett, stage management

Geoff Elliott

Ed Krieger

Reading minds

Over the weekend of May 4-6, South Coast Repertory’s (SCR) Pacific Playwrights Festival held its 10th Annual encampment in Costa Mesa. Seven plays had their first public airing: four as script-in-hand readings, one a semi-produced workshop with five performances, and two in full productions whose multi-week runs overlapped the three-day Festival weekend. It was also a gathering of the American theater tribe – writers, administrators, funders, directors, literary managers, the public, and members of the media (including this writer, who, for full disclosure, previously worked here).

The writer roster split between four stalwarts of SCR’s stable and three younger scribes in their first presentation here. Among the vets were Richard Greenberg, Donald Margulies, José Rivera, and John Strand. The newcomers were Kenneth Lin, Julie Marie Myatt, and David Wiener. In a nice twist, Lin, Myatt, and Wiener benefited from the larger investment of full productions and the workshop staging while the elders provided the reading material.

The Festival is a chance to survey what is on the minds of today’s American playwrights. Admittedly, the results require serious qualifying: writers are a very independent group to begin with, and any assessment must take into account the high-gauge screen of the theater’s selection process. Still, one theme that early on threatened to make this the "Specific" Playwrights Festival was an issue confronting everyone, especially the middle-aged writers.

In Greenberg’s Our Mother’s Brief Affair, Rivera’s Boleros for the Disenchanted, and Lin’s Po’ Boy Tango, the impact of a parent's recent or imminent passing was particularly important. Both of the productions, Myatt’s My Wandering Boy [review] and Wiener’s System Wonderland [review], flipped the dynamic in different ways. In Myatt’s story, it's the younger generation that is lost. In Wiener’s drama, the generational succession is a Hollywood tale of careers, fame, loyalty, and the subject writers find hardest to resist: writers.

Among the broader issues was Wiener’s investigation of creativity in a commercial industry and a nicely turned bit of culture clash in the kitchen of Lin’s Tango. Here, a raw, regrettable showdown between Asian American and African-American friends becomes a riveting moment that, at least by measure of its uniqueness here, was the Festival’s proudest.

The less-heralded but always exciting aspect of this play festival is the acting and directing. Readings and workshops, when employing this level of excellence and cast with this sensitivity of actor to role, are a theater sub-genre that deserves considerably more respect than it gets with the play development process.

Veterans of hundreds of readings know that one of the secrets of contemporary theater is that a play's reading may be more powerful than its first productions. There's blue flame intensity when great acting meets great writing under competent but unintrusive direction that gives the playwright’s words a special clarity. The joy of experiencing words gleaned verbatim from the page, without concern for blocking, hitting a mark, finding the light, costume malfunctions, and pre-set props is an art apart.

This year’s company was deep as usual, and there wasn’t a misstep among the lot. A few marathoners who tackled especially tough assignments with award-winning panache should be singled out: Arye Gross and Jill Clayburgh in the Greenberg play; Greg Itzin in Margulies’ Shipwrecked, a theater-celebrating adventure tale; Danny Blinkoff and John Vickery in An Italian Straw Hat, Strand's musical adaptation (with composer Dennis McCarthy) of the classic farce by Eugene Labiche; Gary Perez and Adriana Sevan in Rivera’s memory play; and Nelson Mashita and Kimberly Scott for their parts in Po’ Boy, which included the aforementioned face-off.

There were news items here, too, with the release of a new six-play anthology published from the catalogue of scripts presented here over the first nine years. Also, SCR announced an award of grant money from the Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust to Culture Clash. It will support another in their series of explorations of American communities. That one, which will survey the Orange County community around South Coast Repertory, could make the 11th Pacific Playwrights Festival a very hot ticket.

top of page

PACIFIC PLAYWRIGHTS FESTIVAL

10th Annual

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

September 5-October 5, 2008

(Opened 9/12, rev'd 9/13m)

CAST: Daniel Blinkoff, Dan Butler, Michelle Duffy, Patrick Kerr, Katrina Lenk, Matt McGrath, Daniel T. Parker, Melissa van der Schyff, John Vickery, Adam Arkin, Jill Clayburgh, Arye Gross, Valerie Mahaffey, Gary Perez, Jonathan Nichols, Isabelle Ortega, Joe Quintero, Adriana Sevan, Sona Tatoyan, Michael Daniel Cassady, Gregory Itzin, Charlayne Woodward Nelson Mashita, Jeanne Sakata, Kimberly Scott

Charlayne Woodard and Gregory Itzin

Henry DiRocco

Facing the facts

One of the most satisfying scenes in David Henry Hwang’s new Yellow Face, a play full of satisfying scenes, is the face-off between a playwright named David Henry Hwang and an unnamed New York Times reporter. The playwright has taken the unusual step of making himself the protagonist in this cracked-lens look at identity, cultural loyalties and the relative reliability of commercial theater and commercial journalism. The meeting between the writers ends after each gets his story: an exposé of Hwang’s father for the two-faced journalist, and a final chapter for Hwang in the saga that will become Yellow Face, premiering through July 1 at the Mark Taper Forum in a co-production with New York’s Public Theater in association with L.A.’s East West Players.

To both ape and undercut the media’s claim of objectivity, Yellow Face employs the scattershot quoting of headlines, bylines and datelines to identify its events and characters. Rather than reflecting on history – as set designer David Korin’s wood deck and massive gold-framed mirror suggest – Hwang at first seems to be transcribing it. The more these citations punctuate the script, however, the more holes they produce in it. Soon, we are in a limbo where fact and fantasy, whether on stage or front page, are indistinguishable.

As Hwang told Sylvie Drake in LA Stage, "Some of the stuff in the play is true and some of it isn’t and I hope it’s hard to tell the difference."

The seesawing between drama and documentary serves Hwang’s larger goal of revealing the cost of prejudice in real terms while showing its utter absurdity through farce. This is accomplished through his own powerful writing and the strong yet playful direction of Leigh Silverman. Silverman holds the tonal teeter-totter for her Asian and Caucasian cast, who balance their alternately scary or silly performances upon it. Future productions of this play, however, will only be this good if they can rest on the kind of sharp-yet- solid fulcrum provided by Hoon Lee's performance as Hwang. In one of the region's best stage performances so far this year, Lee makes simultaneously getting the laughs and landing the punches look easy.

Ironically, Hwang credits stories in The New York Times with inspiring his M. Butterfly, the take on the Puccini opera that became a landmark Broadway hit in 1988 and made the 31-year-old the first Asian American playwright to win a Tony for Best Play. Whatever gains for Asians came with his success were immediately challenged when mega-producer Cameron Macintosh announced that Miss Saigon, which had opened its record-breaking London premiere in 1989, was heading to Broadway with its London stars, including Caucasian Jonathan Pryce as the Eurasian "Engineer,"

The protests were quick and protracted.

The producer compounded the indignity by saying he was unable to find an Asian American good enough for the role. In his newfound prominence, Hwang was faced with a lose-lose decision. He could be loyal to the commercial theater that had helped make him a star, or be an advocate for the community that had helped make him a man.

What transpired is both reported and satirized in Yellow Face, which incorporates Face Value, Hwang's failed mid-'90s spoof of these issues. As Spike Lee's Bamboozled did with the hypocrisy of blackface, Face Value had done with yellowface, a performance style in which Caucasian actors tinted their skin and pulled their eyelids to evoke an Asian look. As bizarre as it sounds now, stars as big as Marlon Brando, Katherine Hepburn and Mickey Rooney joined the ruse.

Like Bamboozled, Face Value could not work its brilliant satire into sustainable drama, and famously closed its Broadway run after previews. But, thanks to Yellow Face, it is now part of this hysterical history lesson.

Among the stand outs in the cast are Tzi Ma in numerous roles including Hwang’s father, and Peter Scanavino, as the white man who becomes a leading Asian personality based on some resumé tinkering. (By putting him in The King and I, Hwang reminds us of Lou Diamond Phillips, who starred in a recent tour of that warhorse after gaining fame in La Bamba, directed by the same Luis Valdez who had his own casting nightmare with a Frida Kahlo biopic.)

Others who give multiple dimensions to multiple personalities are Julienne Hanzelka Kim, Lucas Caleb Rooney, Tony Torn and Kathryn A. Layng, the real-life wife of the playwright who, despite Yellow Face's careful blurring, knows exactly where the newspaper ends and the fish-wrapper begins.

This world premiere is a co-production of Center Theatre Group in L.A. and The Public Theater in Manhattan. At press time, the Public’s press office confirmed that the play would be produced in its 2007-08 Season, but the exact slot was yet to be announced. The production is also made in association with East West Players, which America’s paper of record called "the nation’s pre-eminent Asian American theater troupe." There will not be a separate run at East West – whose main stage is named for this playwright, and whose health is in part owed to his father.

top of page

YELLOW FACE

by DAVID HENRY HWANG

directed by LEIGH SILVERMAN

MARK TAPER FORUM

May 10-July 1, 2007

(Opened May 20, rev. 5/20)

CAST Julienne Hanzelka Kim, Kathryn A. Layng, Hoon Lee, Tzi Ma, Lucas Caleb Rooney, Peter Scanavino, Tony Torn

PRODUCTION David Korins, set; Myung Hee Cho, costumes; Donald Holder, lights; Darron L. West, sound; James T. McDermott/Elizabeth Atkinson, stage management

HISTORY Produced by Center Theatre Group and The Public Theater in association with East West Players World Premiere