MAY 2012

Click title to jump to review

CYRANO by Hershey Felder | Fountain Theatre

GOOD PEOPLE by David Lindsay-Abaire | Geffen Playhouse

THE ILLUSION by Pierre Corneille | A Noise Within

JITNEY by August Wilson | South Coast Repertory

NOBODY LOVES YOU by Itamar Moses and Gaby Alter | The Old Globe

THE SCOTTSBORO BOYS by John Kander, Fred Ebb, David Thompson | The Old Globe

A show of hands

The love triangle at the heart of Edmond Rostand’s 115-year-old Cyrano de Bergerac gets a unique new sounding in Stephen Sachs’ Cyrano, receiving its world premiere at the Fountain Theatre that Sachs runs with Deborah Lawler and the show's director, Simon Levy.

For this co-production with Deaf West Theatre, Sachs trades Cyrano’s oversized nose for deafness. No longer a soldier, Cyrano (Troy Kotsur) is a silent, struggling poet whose words, delivered by American Sign Language (ASL), become a fanciful pantomime of facial expressions and balletic hand movements. Rostand's beautiful, brilliant cousin Roxanne is now Roxy (Erinn Anova). But our 21st Century Cyrano has only glimpsed the beautiful Roxy at the cafe where many of the local deaf community gather for coffee and Sunday night Deaf Poetry Jams.

The update moves the story from one individual with a physical embarrassment to a member of a minority group present in every culture and country. Sachs takes the original character's stymied romantic drive and expands it to symbolize a group's frustrating need to prove parity with the majority – something they should already own as their birthright. A conversation between Cyrano and his friend Bill (Bob Hiltermann) touches on this and draws sighs of recognition from the audience when Bill dismisses empty ifatuations with the hearing–with their hours of laborious ASL instruction–as adolescent foolishness.

Sachs' makeover also integrates modern technology – the Internet, laptops, smartphones, and social media. Posting, texting, and tweeting are basically visual media, and for the deaf they are, as one character says, the "Great equalizer." Cyrano is a complicated man who packs a cellphone and texts and emails without reservation, but disparages Facebook, et al, insisting he is not one of the identical millions but unique: from "a more romantic era." The fact is, he is not romantic at all, having erected a safe barrier to prevent any socializing. His excursions to the café are to show off and defend the poems that cannot speak for themselves. In the famous speech in which Cyrano "out-wits" his mocker with meaner, more clever jabs at his own nose, Sachs’ Cyrano out-insults himself with a hilarious litany like "If a deaf person appears in court do they still call it a hearing?"

Here, as well as the original, Cyrano is infatuated with a woman he believes to be out of his reach. She asks to meet him so she can unburden her heart. He assumes the love she will confess is for him. But it is for his speaking brother, Chris (Paul Raci), an aging rock 'n' roller who is equally infatuated with Roxy. In one of Sachs' many side jokes, it is possible for a rocker like Chris to be successful lyricist without being capable of decent conversation. To help his brother, and feel a connection with Roxy's passion, Cyrano agrees to put words in Chris' mouth – and emails – to help him be the man she wants.

The mix of deaf characters, with hearing who sign and hearing who don't provides the opportunity for various forms of communication. In signed conversations between Cyrano, Bill and Chris, their voices are provided by onstage actors Scott Roberts (Cyrano, in for Victor Warren), James Babbin (Bill), and Al Bernstein (Chris).

Famously, Rostand's Cyrano dies quietly beside Roxanne years after the main story takes place. She has become a nun following Christian's death in battle. Here, Chris dies at the end of a bottle, frustrated by his inability to win true love on his own accord. Sachs' Cyrano, after Roxy exacts the truth of the charade he helped engineer, lives to become a fully engaged member of his community and the world at large.

This production helps move deaf audiences from the corners of one-off ASL performances at major theaters to an experience that puts them at the heart of every performance. When Kotsur produces a bench hidden in the wooden wall of Jeff McLaughlin’s set, it's a reminder that sometimes theater can embolden people who have too long felt like a part of the woodwork.

top of page

CYRANO

by STEPHEN SACHS

directed by SIMON LEVY

FOUNTAIN THEATRE

April 20-June 10, 2012, extended to July 8

Opened 4/28, rev’d 5/25

CAST Erinn Anova, James Babbin, Chip Bent, Al Bernstein, Eddie Buck, Martica De Cardenas, Maleni Chaitoo, Daniel Durant, Bob Hiltermann, Troy Kotsur, Ipek D. Mehlum, Paul Raci, Scott Roberts (in for Victor Warren)

PRODUCTION Jeff McLaughlin, set; Naila Aladdin Sanders, costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; Peter Bayne, music/sound; Jeffrey Elias Teeter, video; Media Fabricators, equipment consultants; Brian Danner, fights; Tyrone Giordano/Shoshannah Stern/ASL masters; Terri Roberts/Bobby Deluca, stage management

HISTORY Co-produced by the Fountain Theatre and Deaf West Theatre (Laura Hill, Fountain; David Kurs, Deaf West; and Deborah Lawlor, Executive Producer. Additional funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. World premiere

Troy Kotsur, Erinn Anova

Photo | Ed Krieger

Uneasy virtue

Maybe what's good gets a little bit better and maybe what's bad gets gone. So wrote Norman Gimbel in the title song to Norma Rae, the Sally Field triumph about a woman's ascent from line worker to union firebrand. Good People, David Lindsey-Abaire's unvarnished tribute to millions of working single-mothers who won't get a Hollywood ending, adds a note of weary resignation to that chorus. "And maybe you just soldier on."

Despite its tale of a late-40s central character who drops from minimum-wage job to unemployment, this is uplifting theater. And, even though she suffers humiliating, seemingly justified dismissal by the successful former boyfriend she has finally asked for help, there is a feeling of triumph. In Matt Shakman's Geffen Playhouse staging (through May 13) he has an ensemble–lead by Jane Kaczmarek, Jon Tenney, and Cherise Boothe– with the depth to sound the play's many levels.

Good People's ironic power to raise our spirits owes to Lindsey-Abaire's instinct to celebrate the fight rather than the victory. In this uncompromising follow-up to his Pulitzer Prize-winning Rabbit Hole, he carefully builds a complex tangle of relationships among his six characters, then refuses any audience-pleasing urge to untangle them for the curtain call.

The human struggle for dignity, which drives his plays, has moved from the extraordinary central characters of his early successes – Fuddy Meers and Kimberly Akimbo – to the average parents reacting to the death of a child in Rabbit Hole, and now to Good People, which settles along the familiarity of America's central political divide. Here, Lindsay-Abaire gives the debate over the value and funding of social programs the human face of a woman refusing to tumble into our widening education and income gap.

"You made bad choices," Mike (Tenney), a Boston physician, tells Margie (Kaczmarek), a woman he briefly dated at the end of high school. "I made choices?" she shoots back incredulously. The play suggests that concepts of "choice," "luck," "hard work" and even "goodness," may be part of accepting personal responsibility, or acknowledging the vagaries of fate, but they ignore the collective responsibility of society.

It begins in the first scene, where Stevie (Brad Fleischer), Margie's supervisor at the Dollar Store, is firing her for seven late arrivals over the past two months. "Not like I have a choice in this," he insists. Margie reminds him that she can't leave home until someone arrives to be with her mentally retarded adult child. And, because she can't afford a real caretaker, she relies on Dottie (Marylouise Burke), her unpredictable landlord who, because it's a favor, can't be pressured.

In Act I we see how Margie lives on a shoestring, filling her social life with economy entertainment: TV, gossiping with Dottie and longtime pal Jean (Sara Botsford), and playing Parish Bingo, another nod to indifferent luck. Meanwhile, having no luck with job interviews, she reluctantly takes Jean's advice to go visit Mike, whom she hasn't communicated with in 30 years, and ask if his office needs help. It does not. She is convinced he has rejected her because her poor South Boston accent and wardrobe remind him of the "Southie" poverty he left behind. While he's brushing her off with promises to ask around, she inveigles an invitation to his upcoming birthday party. When he later calls to cancel, she is sure he's only calling her, wanting to avoid the embarrassment of her mingling with his wealthy friends. The act ends with her decision to crash the party.

For Act II we move to Mike's tasteful two-story home in an upscale suburb. Margie arrives and reveals costumer E.B. Brooks' perfect choice for the occasion. An unflattering outfit that screams discount rack. It's a top-and-slacks outfit that could only be chosen by someone who doesn't have a choice. She finds that Mike and his wife Kate (Cherise Boothe, right) have indeed canceled the party because of a sick child..

In the tough neighborhoods of South Boston, where Lindsay-Abaire grew up, race is still divisive. A white man is shunned for dating an Asian and the black mother of a light-skinned, mixed-race baby is assumed to be its nanny. However, by making Kate an African-American of higher station than Mike, Lindsay-Abaire makes race secondary to Margie's story of the economic gulf between haves and have-nots. Mike breached it. The others did not.

Kaczmarek gives Margie all the shadings of humor, bitterness, resolve and resilience that we need. The extended second act scene with Tenney and Boothe (whose various appearances in these pages – recently Speed-The-Plow and Milk Like Sugar, respectively – have been exceptional) builds slowly towards its explosive end. All three are basically good, caring people who will go out of their way to help others. And yet, mistakes, misinformation, and indifferent fate can throw the best people into a lose-lose situation that burns through any hope for reconciliation.

The Act I scenes with the women are less satisfying, however. Burke's scattered landlady gets laughs but puts the play in neutral. The performance recalls the gold standard for dotty dames, Ruth Gordon. But Gordon's flightiness always seemed somehow knowing, and it might be more effective if Dottie were less so, and more cagey in her kookiness. Botsford's Jean is flinty, a gum-chewing Southie who eventually feels one-note, without goals of her own other than to straighten out others and help Margie.

Shakman makes his Geffen directorial debut trailing impressive credentials for work with his Black Dahlia Theater. He also brings some of his colleagues for the physical production, including Brooks, Set Designer Craig Siebels, and sound designer/composer Jonathan Snipes (whose score includes pan flute or pennywhistle to gently echo the harsh but redemptive Ireland that still influences its emigrees in South Boaton). Elizabeth Harper adds lights.

Good People resonates long after the curtain call. Despite the bleakness facing Kaczmarek's Margie, we know she is determined to fight on for her dignity and her daughter's welfare. It's a dramatic endorsement for U.S. programs that promote jobs, training, health care, and safety, and pay true dividends for America beyond the trickle-downs of market rallies. If U.S. Representatives want to approve funding to pay for sack lunches, Sports bottles, and a charter bus to a performance of Good People when it plays the Arena's Kreeger Theater in February 2013, that would be tax dollars well spent. It should finally help get their priorities straight.

top of page

GOOD PEOPLE

by DAVID LINDSEY-ABAIRE

directed by MATT SHAKMAN

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

April 11-May 13, 2012

Opened 4/11, rev’d 5/5m

CAST Cherise Boothe, Sara Botsford, Marylouise Burke, Brad Fleischer, Jane Kaczmarek, Jon Tenney

PRODUCTION Craig Siebels, set; E.B. Brooks, costumes; Elizabeth Harper, lights; Jonathan Snipes, music/sound; Jill Gold/Kyra Hansen, stage management

Jane Kaczmarek, Jon Tenney and Cherise Boothe

Michael Lamont

Love's Illusion

The playfulness with which first Pierre Corneille (1606-1684) created The Illusion and in which Tony Kushner "freely adapted" it for 20th Century audiences, is unmistakable in Casey Stangl's current staging at A Noise Within (through May 19).

Structurally daring, then as now, the work weaves its way through conceits within motifs until it arrives with a flourish at a surprise ending that pulls us back from the stories within the story for perspectives on passion that are simultaneously expansive in meaning and reductive in relevance for us real theatergoers sitting in the room.

As always, Kushner's mastery of dramatic writing pulls us along. Stangl keeps things infused with energy to drive the play through a game of hide-and-seek reality and illusion play with each other. It is welcome reminder of the contributions these two titans have made to theater.

Kushner felt strongly that Corneille's play had a pre-Romantic cynicism to which his modern audiences could relate. Through this honest appraisal of love's precariousness, and disappointment waiting to swallow those who fail and fall, he knew the ultimate message could be one of greataer appreciation for the life-affirming powers of love.

In an interview, Kushner called it "a passionate, very French play about love, disappointment and disillusion." But, he found in it something that resonated with contemporary attitudes: "There's a certain rational skepticism about where love leads and willingness to look at love with a jaundiced eye and that seems very modern to me."

The framing device for this multi-angle, shifting-reality view of fathers and sons, loves and lovers, is that Pridament (Nick Ullett) has sought out the magician Alcandre (Deborah Strang) to help him find his missing son, Calisto (Graham Hamilton). Once inside her cave he is at the mercy of her powerful manipulations of perception. With the aid of her assistant, the mute Amanuensis (Jeff Doba), the wily magician conjures up visions of what is – or only may be – occurring with his son and several of those he meets in his travels.

There is the beautiful, inquisitive Melibea (Devon Sorvari), her conniving attendant Elicia (Abby Craden), Melibea's daft suitor Pleribo (Freddy Douglas), and a wealthy eccentric named Matamore (Alan Blumenfeld).

Hamilton is a likeable lead, with Strang strong as always, and the sultry Craden working her wiles. Both Douglas and Blumenfeld add to their list of great guest appearances, and Doba appears in the second act, shedding his soundless magician's assistant in a wonderful act of chrysalis.

Keith Mitchell's successfully simple set has a spacious stage space for the action, with dark, rough cave walls upstage. Julie Keen dresses the characters in a rich and varied costumes, while the busy Jeremy Pivnick keeps the integrity of the cave's blackness while illuminating the actors. Doug Newell provides the sound, while Ken Merckx provides his usual high level of fight choreography.

top of page

THE ILLUSION

by PIERRE CORNEILLE

adapted by TONY KUSHNER

directed by CASEY STANGL

A NOISE WITHIN

March 10-May 19, 2012

Opened 3/17, rev’d 5/19e

CAST Alan Blumenfeld, Abby Craden, Jeff Doba, Freddy Douglas, Graham Hamilton, Devon Sorvari, Deborah Strang, Nick Ullett, with Katherine Lee, Alex Parker, Michael Sanchez

PRODUCTION Keith Mitchell, set; Julie Keen, costumes; Jeremy Pivnick, lights; Doug Newell, sound; Ken Merckx, fights; Dale Alan Cooke, stage management

Deborah Strang, Jeff Doba

Photo | Craig Schwartz

In service

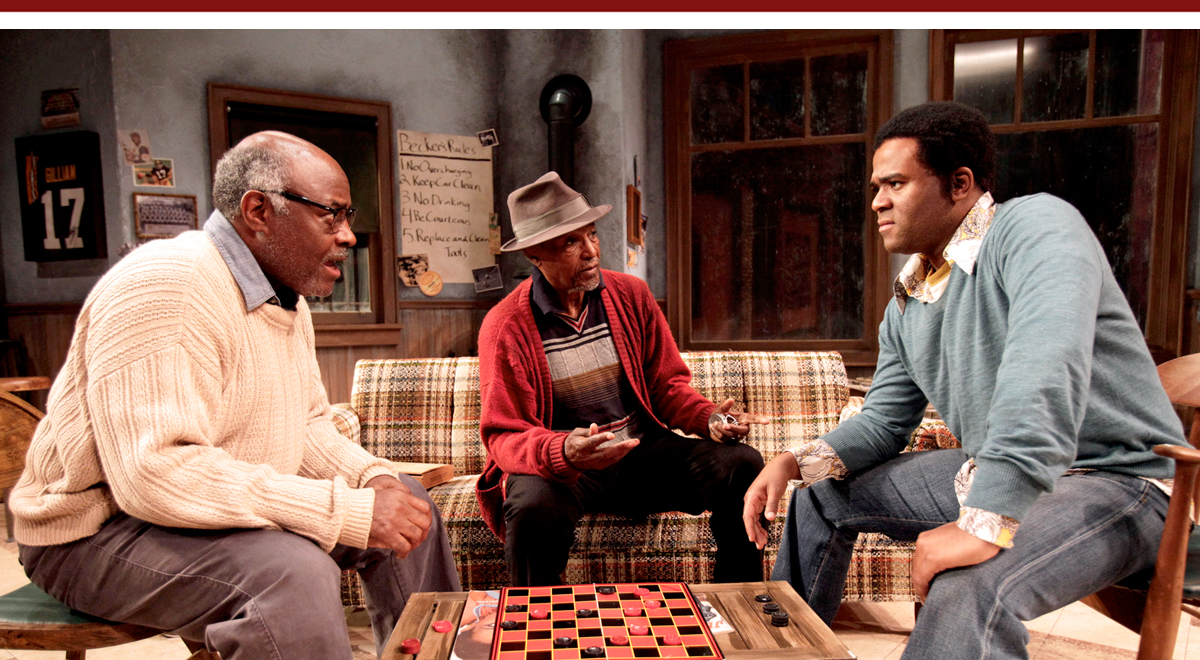

In August Wilson's play-per-decade journey through the 20th Century, Jitney is the only one of the ten scripts set at the time it was written. The currency that gives the dialogue and characters is echoed in director Ron OJ Parson's respectful, respectable production on South Coast Repertory's main stage (through June 10).

In 1978, for what would become the first installment of his landmark series, Wilson looked to the poor Pittsburgh neighborhood in which he lived for experiences that would speak to the greater struggles and strengths of contemporary Black America. He found them in scattered storefronts around the Hill District, where laid-off, retired, and underemployed men provided honest, if not legal, "gypsy cab service" for a black community the city's taxi companies refused to enter.

The jitneys made it possible for carless seniors to reach their doctors, mothers to carry home groceries, and rumpled night owls to return to the wives who waited with the cold light of dawn. They now made it possible for Wilson to explore how men handled their responsibilities–to each other, to the women in their lives, and to the world outside the District that called them to war and nothing else.

Jitney is primarily a character study with two arterial storylines moving it along. The first is the broken relationship between Jim Becker (Charlie Robinson) and his son, Booster (Montae Russell), who has just finished a 20-year sentence for murder. The second involves Darnell, or "Youngblood" (Larry Bates), and his girlfriend Rena (Kristy Johnson).

While the young lovers' story moves through misunderstanding to mutual respect – thanks to an echo of improving women's rights in Rena's insistence on true partnership – the elder Becker refuses to reconcile. Believing his son's crime caused his broken-hearted wife's early death, he sees Booster's crimes as double-murder, and his parental responsibilities towards him dissolved. Between these stories of reconciliation and rejection a series of portraits are provided.

In addition to Vietnam veteran Darnell and Becker, the other drivers are Turnbo (Ellis E. Williams), a meddlesome old trouble-maker; Doub (James A. Watson Jr.), a father of two, former railroad worker, and Korean war vet; and Fielding (David McKnight), onetime personal tailor for Billy Eckstein and other jazz legends, now an alcoholic constantly on the verge of losing his job. Floating through the mix are a numbers runner named Shealy (Rolando Boyce) and Philmore (Gregg Daniels), a hotel doorman who too often wakes in the wrong woman's room.

Hanging over the day-to-day struggles of these men is the coming urban redevelopment project that will demolish this section of the Hill. The drivers discuss purchasing the property themselves, or moving as a group to a new location. To get extra money for the cause, Becker takes a night shift back at the mill. It will be his last, and bring about a new era that will test how all the men will rise or fall without this inspirational father figure.

Parson's authenticity settles over the production like a protective blanket. It provides for realness, which manifests as the casualness of normalcy, in an unhurried depiction of the day-to-day. In Robinson, it is appropriately minimalist, running his crew with practiced sternness and fairness. Williams' Doub, too, is a strong, silent lieutenant, while Bates' Youngblood is as hot-tempered as his name requires. In the others, however, Parson's protective blanket is the spark arrester that prevents overt eccentricities, keeping it real but muffling vivid color and fireworks. An overall flatness is echoed in Shaun Motley's exacting replica of a dull storefront with practical fluorescents (and designer Brian J. Lilienthal's curious choice not to provide daylight on the painted street flats outside the large office window).

But the era's sights are vividly captured in Costumer Dana Rebecca Woods’ test-pattern plaids, popsicle-colored suits, and flared pants, while its wonderful sounds are revived in the smooth-funk soundtrack designer Vincent Olivieri has woven from hits by Roy Ayers, War, LTD, Miles Davis, and Kool and the Gang. The SCR hall never sounded so good.

top of page

JITNEY

by AUGUST WILSON

directed by RON OJ PARSON

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

May 11-June 10, 2012

Opened, rev’d 5/18

CAST Larry Bates, Rolando Boyce, Gregg Daniel, Kristy Johnson, David McKnight, Charlie Robinson, Montae Russell, James A. Watson Jr., Ellis E. Williams

PRODUCTION Shaun Motley, set; Dana Rebecca Woods, costumes; Brian J. Lilienthal, lights; Vincent Olivieri, sound; Ken Merckx, fight consultant; Jamie A. Tucker/Chrissy Church, stage management

Ellis E. Williams, David McKnight and Larry Bates

Photo | Henry DiRocco

Take heart

Playwright Itamar Moses has met his match in Composer Gaby Alter. Contributing the gifts of their respective disciplines they share lyric-writing chores and turn a walk down the worn path of love stories into a zippy, giddy, contemporary romp that pokes fun at everything and promises to tickle everybody.

The world premiere of Nobody Loves You, in the Old Globe's smaller theater-in-the-round (through June 17), is evidence that theater can court a younger audience to replace its graying sugar daddy. That Alter-Moses gleefully mock both the cultural wasteland of reality TV and the culture snobs who dismiss it is evidence that these two are both wise in reach and capable in grasp.

Credit for the fast-passing hour-and-45-minute blast also goes to director Michelle Tattenbaum and her musical team of choreographer Mandy Moore and music director Vadim Feichtner. The four-male, four-female cast, singing Alter's vocal arrangements, adds eight exclamation points to assurances that "America's Got Talent."

The black comedy title is the name of the reality show within the show. Each season, "NLY" mixes equal parts single men and women in a cam-crammed living space for unscripted dating, mating, and parading before a voyeuristic America. Each week the viewer-voters end one more contestant's chances for romance, ratings and a 50 share, sending the lonely heart home to the tune of "Nobody Loves You," sung by the show's vapid host, Byron (Heath Calvert).

We begin with Jeff (Adam Kantor) writing his ontology dissertation about perception and reality while girlfriend Tanya (Nicole Lewis) watches the season finale, which includes a call for next season's hopefuls. Jeff's disinterest in sharing remote TV romance convinces Tanya (who isn't interested enough in him to distinguish ontology from optometry) that the relationship should end with the TV season. She leaves announcing she will seek her true love as an NLY contestant.

Compelled to win her back, Jeff submits a pathetically heart-felt video to the show and is urged to be part of it, even after Tanya withdraws to enjoy the new boyfriend she found on her own. He tells the show's producer, Nina (Lewis, again), assistant, Jenny (Jenni Barber), and Byron that he'll participate, half-heartedly, if only to research his refocused dissertation on "the gaps between how we perceive reality and how it may intrinsically be."

Joining Jeff for the new season are Megan (Lauren Molina), a partying, sex-and-alcohol-loving free spirit; Samantha (Kate Morgan Chadwick), a proper love-seeker with a knack for futile attractions; Dominic (Alex Brightman), a gratingly self-assured ladies man; and Christian (Kelsey Kurz), just what the name implies.

Jeff avoids the many manufactured opportunities to connect – the 3D room, pillow-fighting room, mirror room, obstacle course of love, each of which provides more opportunities for Moses-Alter lyricism, in which even the oddest phrase can be part of a happy couplet, and Alter's rock-driven show tunes. The one fan we meet, Jenny's roommate Evan (Brightman, again), has a creative use of hashtags that gives the writers a source of hilarious, stanza-ending buttons.

It is a waste of time and space to cite individual virtues of this cast. Theykeep their characters real within the show's unreal comic context. They'd make a ho-hum show worth watching. With this invigorating material, the acting, singing, and dancing simply soars. Only because we've seen and reviewed her before, in John Doyle's Sweeney Todd, will we mention Ms. Molina. Called on for the most revealing moments, the former Joanna shows commitment enough to eliminate any trace of her character's potential cliché. And, she is matched in versatility and talent by the other seven.

The musicians under keyboardist Feichtner's direction are Vince Cooper (guitars), Michael Pearce (bass), and Kevin Koch (drums). Michael Schweikardt's set is a glossy floor with inset light boxes and a center disc that rises for a singing platform, sinks for a spa, or remains level for the dance floor and studio. There's a couch for Jeff's and one for Jenny's and a few hollowed out wooden TV frames scattered about for monitors. Emily Pepper designs appropriate costumes for both the folks at home and the folks in TV Land, while Tyler Micoleau lights with the same distinctions.

Moses, who seemed at the top of his game in his recent Completeness, has gone beyond. Jeff's ultimate match may be as obvious from their first meeting as is his mismatch with Tanya, but the rewarding surprises aren't in the plot. They are in the writing and performing. Lyrics are rich and contemporary and clever and rarely if ever does the disciplined pair reach for a rhyme. Moses and his Alter-ego have given the tired old boy-meets-girl, boy-loses-girl plot an entertaining new twist that is cause to celebrate. The last show that gave us such encouragement was Kristoffer Diaz' Welcome to Arroyo's, on this same Stage. Somebody's doing something right.

top of page

NOBODY LOVES YOU

music and lyrics by GABY ALTER

book and lyrics by ITMAR MOSES

choreographed by MANDY MOORE

music direction by VADIM FEICHTNER

directed by MICHELLE TATTENBAUM

OLD GLOBE THEATRE

May 9-June 17, 2012

Opened 5/17, rev’d 5/26e

CAST Jenni Barber; Alex Brightman, Heath Calvert, Kate Morgan Chadwick, Adam Kantor, Kelsey Kurz, Nicole Lewis, Lauren Molina

ORCHESTRA Vadim Feichtner, music director/conductor/keyboard; Vince Cooper, guitars; Michael Pearce, bass; Kevin Koch, drums; Steven Withers, synthesizer programming; Brett Macias, contractor

PRODUCTION Michael Schweikardt, set; Emily Pepper, costumes; Tyler Micoleau, lights; Paul Peterson, sound; Gaby Alter, Orchestrations and Vocal Arrangements; Hannah Ryan, asst. director; Peter Van Dyke/Leighann Enos, stage management

HISTORY Recipient of an Edgerton Foundation New American Plays Award and support from the National Fund for New Musicals, a program of National Alliance for Musical Theatre. World Premiere

Adam Kantor, center, with, left to right, Kate Morgan Chadwick, Nicole Lewis, Alex Brightman, Lauren Molina, and Kelsey Kurz

Photo | Henry DiRocco

Railroaded

Cosmeticians apply facial masks to stimulate the skin and, as they peel them off, extract impurities. In the musical The Scottsboro Boys, receiving its West Coast premiere at The Old Globe (through June 10), the show's creators apply the mask of minstrelsy to their storytelling so that, when the characters remove the blackface in a third-act act of defiance, public complacency might be peeled off with it and greater awareness stimulated.

Sadly, the 80-year-old story of how nine innocent African-American teenagers were convicted on a trumped-up rape charge is not out-of-date. Not when, on the night before the performance reviewed here, an African-American man living only miles from the theater announced that after five years in prison for a rape he vehemently denied, the accuser admitted she had lied.

By using minstrelsy's blackface, cartoonish costumes, and exaggerated stereotypes for the narrative's principle guides, composer-lyricists John Kander and Fred Ebb, author David Thompson, and director-choreographer Susan Stroman employ a theatrical travesty to lay bare a judicial one.

In the forward to Inside the Minstrel Mask, the editors call blackface minstrelsy "the chief American popular entertainment of the 19th Century," and "truly significant in shaping American ideas about race, class, and gender." The stereotypes it perpetuated helped justify public complacency that was complicit in the men spending a combined century in prison before all were exonerated. And there were countless other incidents, usually settled not by trial but by lynching.

That these songs are written by a pair of mainstream musical theater legends has a sublime resonance of the mass-appeal entertainments that are being mocked. It is Thompson's book that lays the tracks for Stroman's sure direction and inspired choreography. From the first, unhurried moments, we feel the firm hand of someone who intuitively knows the pulse every moment demands. She gets the mix of contradictory styles to reveal the uncomfortable truths hiding behind the exaggerated smiles.

"No crime in American history," writes Douglas O. Linder in his exhaustive Scottsboro Boys article, "let alone a crime that never occurred, produced as many trials, convictions, reversals, and retrials as did an alleged gang rape of two white girls by nine black teenagers on a Southern Railroad freight run on March 25, 1931.

During the depression, laborers looking for work would travel from town to town by train. The Southern Railroad freight route from Chattanooga to Memphis, two cities along the southern edge of Tennessee, traveled through Alabama. On that Spring day in 1931 the train carried a couple dozen of these migrants, including nine black teenagers and two white women scattered atop the cars. One white rider walking along a boxcar roof stepped on the hand of one of the older black riders, Heywood Patterson, who was holding on from the side. A fight erupted and it ended when all but one white rider were chased off. Some of the derailed boys complained to a stationmaster and he alerted the police at the next stop who were waiting with dozens of armed men to arrest those involved in the fight. Instead, they simply arrested every black rider and locked them in the nearest jail, in Scottsboro. The two women added fuel to the mob anger by claiming that they had been raped by the black men.

Trials began with a fortnight and lasted through a series of retrials that went on for six years. The interminable process is described in detail in the article referenced above and a PBS documentary (linked at right) and many books and films. The Scottsboro Boys does well to take us through it, but with the important added dimension of illuminating theatricality.

In a circus atmosphere presided over by the Interlocutor (Ron Holgate, looking like Uncle Sam in Colonel Sander's suit), 17 new Kander & Ebb songs, with titles like "Chain Gang," "Alabama Ladies," "Commencing the Chattanooga," propel the 105-minute, intermissionless show, helping move the narrative while also maintaining minstrelsy's variety show pacing.

The Interlocutor is abetted by two outrageous minstrel show characters, Mr. Tambo (Jared Joseph) and Mr. Bones (JC Montgomery), in wild costumes by Toni-Leslie Jones that would make the most ridiculous vaudevillian look reserved. Tambo and Bones are co-narrators who fill in as many of the story's principle characters. The nine Scottsboro Boys are played by a versatile ensemble led by Clifton Duncan as Patterson. The others are David Bazemore as Olen Montgomery, Nile Bullock as Eugene Williams, Christopher James Culberson as Andy Wright, Eric Jackson as Clarence Norris, Kendrick Jones as Willie Roberson, James T. Lane as Ozie Powell, Clifton Oliver as Charles Weems, and Clinton Roane as Roy Wright. When portraying their characters, the performances are dramatic and compelling. However, when called on to play side characters who get the cartoon treatment, they transform instantly and completely.

One more character is woven through the story. The lone woman in the play, simply identified as The Lady (C. Kelly Wright), is a mysterious presence serving whatever function is called for. The show opens as she waits on a bus stop, with a pastry box ala Forest Gump, and then, like Gump, seems to be everywhere observing what is happening. She may be a mother, a sister, a girlfriend, or a member of a crowd, but she is a conscientious observer who will gather all these experiences that we watch and, with the clarity that comes once the masks and blinders are removed, utter her only line of dialogue. Wright provides a transcendency here, magically lifting the already superior musical into another realm of significance.

top of page

THE SCOTTSBORO BOYS

music and lyrics by

JOHN KANDER & FRED EBB

book by DAVID THOMPSON

directed and choreographed by

SUSAN STROMAN

THE OLD GLOBE

April 29 - June 10, 2012

Opened 5/5, rev’d 5/26m

CAST David Bazemore, Cornelius Bethea, Nile Bullock, Christopher James Culberson, Clifton Duncan, Ron Holgate, Eric Jackson, Jared Joseph, James T. Lane, JC Montgomery, Clifton Oliver, Clinton Roane and C. Kelly Wright, u/s Audrey Martells, Shavey Brown, and Max Kumangai

ORCHESTRA Eric Ebbenga, music director/conductor/piano/harmonium; Healy Henderson, violin; John Reilly, trumpet/cornet/flugelhorn; David Pollock, trombone; Justin Grinnell, bass; Scott Sutherland, tuba; Dave Mac Nab, banjo/guitars/mandolin/ukulele/Harmonica; Tim McMahon, drums/percussion; Lorin Getline, contractor

PRODUCTION Beowulf Boritt, set; Toni-Leslie James, costumes; Ken Billington, lights; Jon Weston, sound; Rich Sordelet, fights; Joshua Halperin/Evangeline Rose Whitlock, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere at the Vineyard Theatre in New York City, February 2010. Broadway premiere at the Lyceum Theatre, October 31, 2010. A co-production with American Conservatory Theater. West Coast premiere

MEDIA PBS Documentary on Youtube, and additional resources, and The Old Globe video preview