APRIL 2011

Click title to jump to review

BASH: LATTERDAY PLAYS by Neil LaBute | Coeurage Theatre Company

THE ECCENTRICITIES OF A NIGHTINGALE by Tennessee Williams | A Noise Within

THE ESCORT by Jane Anderson | Geffen Playhouse

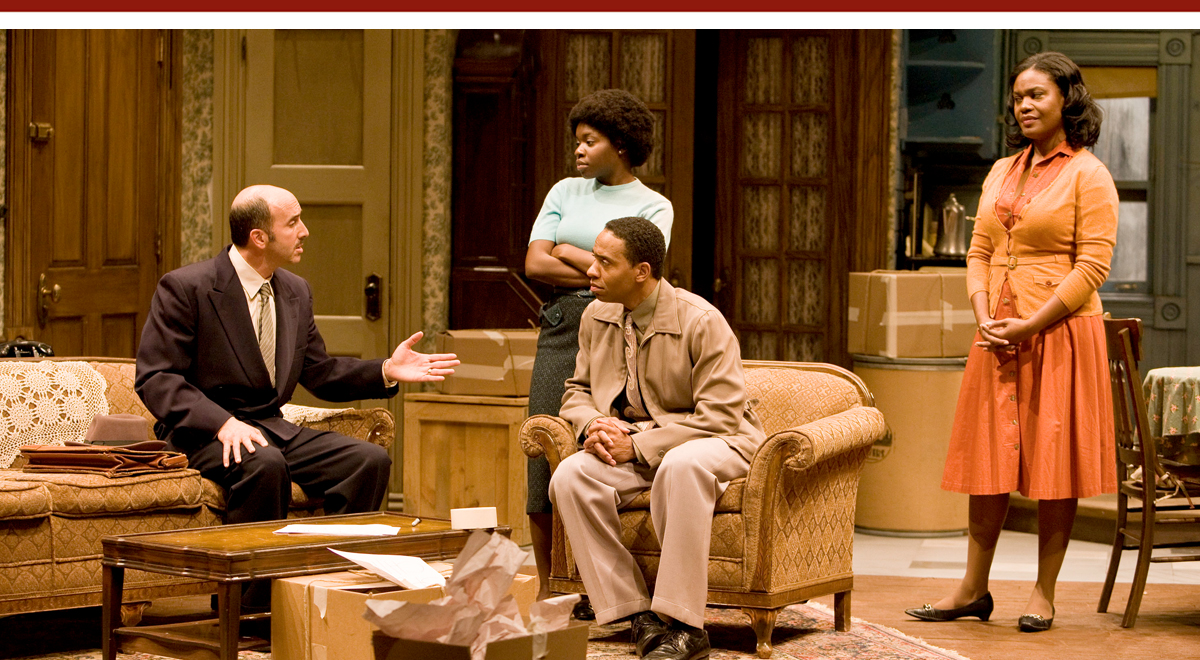

A RAISIN IN THE SUN by Lorraine Hansberry | Ebony Repertory Company

Those kinds of people

Coeurage Theatre Company's production of Bash offers three one acts of vintage Neil LaBute that is essential viewing for his fans and a good sampler for the uninitiated. With performances that range from good to exceptional, and a pay-what-you-will pricing policy for the entire run, the experience is like finding a collector's item at a 99c store.

The production, well directed by Meredith Hinckley Schmidt, is at the Artists Circle Theatre (through May 15) on Santa Monica (west of La Brea), with Jessica Anna Blair, Robert Hardin, Sara Lorraine Perry, and Peter Weidman. (The understudies are Artistic Director Jeremy Lelliott, John Klopping and Nicole Monet.)

Like the unifying title that means both a party and a beating, each story has bi-polarity. Four Mormons in their 20s or 30s recount life-changing experiences to an unseen listener inside the fourth wall. Driving each narrative is the need to justify a violent overreaction to how the world really is. The incidents outlined before intermission are sparked by entrenched males who perceive encroachment by women in the workplace and homosexuals in society, respectively. Unlike the protagonists in these two, who only perceive themselves as victims, the third storyteller is a young woman who is seduced and then abandoned by the man who had been her mentor.

Although the play's subtitle is "Latter-Day Plays" and each character is a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), LaBute is not simply pointing the finger at the Mormon church. LaBute chose to became a Mormon in 1981 while attending Brigham Young University's film school. He has two primary messages. First, raising children with group-think certainty (whether religious, political or philosophical), without regard for the rights of others to have opposing views, turns them into pressure-cookers with simmering "us against them" hostilities. And second, the capacity for the kind of monstrous sacrifices we read of – from Homer's Agamemnon to the Bible's Abraham – may be based in human behavior.

LDS elders didn't see it that way, and "disfellowshiped" him with a recommendation not to write about Mormons.

"The man" (Hardin) in the opening narrative, "Iphigenia in Orem," is reeling from a female co-worker's legitimate (if obnoxious) claim against their male-dominated workplace. (Iphigenia is the daughter Agamemnon sacrificed to Artemis, while Orem is a city in Utah.) Because his upbringing in an environment of not questioning and not rebuking has turned his resistance inward, his response will be cowardly, explosive and more harmful to himself than the co-worker.

Hardin shows us the well-polished shell of acquiescence that has made him a good salesman. Not surprisingly, the first person he chooses to hear of his horrible deed, years after it happened, is another salesman. It's a good performance of a challenging role that requires revealing the inner rage and its sources without benefit of supporting words or movements. Hardin gets a lot of it, but we need to come away with a more tangible sense of what sparked it for the piece to be as unnerving as it can be.

In the second story, "A Gaggle of Saints," two college students (Weidman and Perry) travel to New York with two other couples for a fancy "bash." Although they are telling their versions of what happened to separate people, the stories merge into a single narrative with one often finishing the other's sentence. Back in the hotel after the party, the women fall asleep and the guys leave to wander the city.

The party coincides with their sixth anniversary of dating and during a pre-party stroll they had encountered two middle-aged gays engaged in semi-public displays. John is jarred, and justifies his repulsion by assuring his listener that he is very familiar with God's word on the subject. Later, roaming the park with his friends, he again sees one of the men and follows him into a restroom to bait and bash.

Because LaBute has taken the time to fill in the couple's backstory, we understand John's reaction in both psychological terms (the heat under his pressure-cooker was turned up by a condescending father) and religious terms. Again, the results are explosive and cowardly.

Weidman allows us to see the coiled snake inside the affable, even goofy, exterior as he jovially leads us down the path of his recollection. We hear how he met Sue, learn of his tender adoration of her, and even wonder at how he brushes off a violent incident with Sue’s previous boyfriend. Perry’s Sue is an accessory to the story if not the crime. Pretty and sweet, she confirms John's romantic side. There is a quick indication that she may be drawn to violence, however, and Perry is careful not to overplay it.

After the break, we meet a character with almost no connection to the church or religion. Instead, she references the Greek figures and ideas she learned in school. The woman (Blair) is obviously incarcerated, telling her story into a tape recorder for an interiewer outside her interrogation room. More than a decade earlier, as a lonely 13 year old, she was befriended and then seduced by a junior high school teacher. After she becomes pregnant, the teacher she adores shows great interest in the coming baby, which she then proceeds to bear. But, by then the father is gone without a goodbye.

In "Medea Redux," Blair is captivating, able to maintain the mood of her present arrest and simultaneously transport us to happier times. Though she slows for effect, she never allows the piece to drag, like the jazz musician who stays on top of the beat. In fact, kudos to Schmidt for providing the right touch throughout this difficult series. All the actors are rigorous in avoiding eye contact with the audience and controlliing the plays' delicate, changing moods.

The Coeurage Theatre box office remains open after the show, just in case our perspective of 'pay-what-you-will' is different exiting than entering it. It's a smart policy and should happen for this production. Hopefully you will want to encourage the folks at Coeurage. They're those kinds of people.

top of page

BASH:

LATTERDAY PLAYS

by NEIL LABUTE

directed by

MEREDITH HINCKLEY SCHMIDT

COEURAGE THEATRE COMPANY

at the Artists Center Theatre

April 15 - May 15, 2011

(Opened, rev’d 4/16e)

CAST Jessica Anna Blair, Robert Hardin, Sara Lorraine Perry, Peter Weidman, u/s Jeremy Lelliott, John Klopping, Nicole Monet

PRODUCTION Debbie Dufour, costumes; Michelle Stann, lights; Joe Calarco, sound; Ric Perez-Selsky, stage management

HISTORY The plays premiered at the Douglas Fairbanks Theater in New York City on June 24, 1999 and featured performances by Ron Eldard, Calista Flockhart and Paul Rudd. The Los Angeles premiere, with the New York cast, the same year.

INSETS: Jessica Anna Blair (top); Sara Lorraine Perry and Peter Weidman

Ric Perez-Selsky

Full-throated

Tennessee Williams' The Eccentricities of a Nightingale is getting a fine revival, or, as central character Alma Winemiller might say, resuscitation, at A Noise Within (through May 28). Deborah Puette is heart-breaking as the pretentious, impassioned Alma, a vicar's daughter who must fall from grace to follow her heart.

The play's languid Southern pulse comes from the rise and fall of Alma's hopes, which Puette, in her ANW debut, keeps anchored in reality despite the character's flirtations with fantasy and affectation. Director Dámaso Rodriguez successfully balances the play's ominous tone with the poetic ornamentation that creeps across Williams' dialogue like moss on a magnolia. Helping are key cast members: Jason Dechert as John Buchanan, who promises release for Alma's pent-up passions; debuting Christopher [sic] Callen as his meddling mother; and company member Jill Hill in a controlled burn as Alma's declining mother.

Williams' 1964 script is a rewrite of his 1947 Summer and Smoke, which was adapted from "The Yellow Bird," a short story he wrote earlier that year (See "On the Reel Side" at right). The most significant change from Summer was swapping John Buchanan, Sr., a relatively passive force, for his wife, who dismisses Alma as unworthy of her son.

The playwright included Alma among his "divided characters," torn between their "puritan and cavalier strains." Williams projects that dual nature into the play's structure, moving the action between summer and winter. and onto Alma's parents. Her reverend father is cool (although the fine Mitchell Edmonds goes beyond cool to colorless), while her mother's scorched memory is seared with the image of a sister's fiery death with her lover.

Our first image of Alma is her silhouette projected onto the canvas back of a raised stage in the town square. She is singing, in an exaggerated vocal and physical style, for the July 4, 1916 celebration in Glorious Hills, Mississippi. She finishes, exhilarated by performing, and joins her parents, only to be cautioned that her mannerisms have cast her as an eccentric by townspeople: "You, you, you – gild the lily!" her father says. "You express yourself in fantastic highflown phrases! Your hands fly about you like a pair of wild birds!"

She dismisses the charges as John arrives. Alma's playmate from childhood is now a handsome doctor fresh from Johns Hopkins. Suddenly her fluttering is not affectation, but flirtation. John encourages her, tossing a small firework under Alma's bench. He may think the gesture is a harmless throwback to childhood pranks, but in Williams' symbology it is a love offering. Later, John will further fuel Alma's hopes when she goes next door in the middle of a wnter night to be treated for anxiety by John's father. But John intercepts her and, ignoring his mother's warnings about getting involved with the odd woman, offers to help. He undoes her blouse and presses a stethoscope against her breast.

ALMA: What do you hear in my heart?

JOHN: Just a little voice saying "Miss Alma is lonesome"

With plenty of justification from the text, Puette moves Alma into action – dropping any affect and directly asking for a New Year's Eve date with John. He agrees, they meet, and take a room "that can be rented by the hour" after Alma convinces John that she may be the most realistic person in Glorious Hills: "Give me the hour and I'll make a lifetime of it."

While Puette lets us see Alma's inner gears working, Dechert does not do enough to help us understand John. He creates an appealing Buchanan with the right mix of ambition and resignation, but what really moves him? When he tells his mother he does not love Alma, is it to silence her or is it the truth? Without a little more information from him, the scene in the hotel room falls short of its potential, as does the following, final scene in which, years later, Alma picks up a traveling salesman in the town square.

Still, Puette (previously seen in Catherine Butterfield's Brownstone), Callen and Hill are so strong, that it becomes a minor point. Also good are Dave Kirkpatrick and Hank Ostendorf as other romantic options for Alma, and the members of her literary circle: David LM McIntyre, who makes the somewhat affected Vernon fun to watch, and Darby Bricker, interesting as a younger member.Jacque Lynn Colton. Erika Salomon, Stefanie Zoe Demetriades and Tameé Seiding round out the ensemble.

Joel Daavid's set is weighted upstage with a cluster of well-rendered elements, notably the angel fountain (named "Eternity") and some large gears that allude to the musee mecanique. The musee is where Albertine and her lover, Mr. Schwartzkopf, died. Schwartzkopf owned the museum and was the one who set the fire. The gears are set in motion to get each act moving. A reductive theme of mechanics is interesting as a metaphor for theatre rather than for the lives in the story. However, the way Daavid's proscenium incorporates an ornate, fractured picture frame out of which the play spills onto the stage, is a beautiful allusion to nature's drive to burst through artiface.

The costumes of Leah Piehl deserve special attention. In her ANW debut, she provides impressive designs, fabrics and execution that create the heavy look of the period. Kellsy MacKilligan assisted her. James P. Taylor's lighting and Andrew Villaverde's sound complement the production.

On May 28, The Eccentricities of a Nightingale will bring the 2010-11 Season to an end, and with it A Noise Within's 19-year residency at its first home, the rented Masonic Lodge in Glendale. Artistic Directors Geoff and Julia Rodriguez Elliott are down to the last million of a $13 million capital campaign to build a custom complex in Pasadena set to open in September. Hundreds of productions and thousands of curtain calls will be represented as the lights dim on Williams' American classic and Ms. Puette's brave Alma. It's quite an honor for the newcomer. And she earns it.

top of page

ECCENTRICITIES OF A NIGHTINGALE

by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

directed by DAMASO RODRIGUEZ

A NOISE WITHIN

March 12-May 28, 2011

(Opened 3/19, Rev’d 4/17m)

CAST Deborah Puette, Mitchell Edmonds, Jill Hill, Jason Dechert, Christopher Callen, Dave Kirkpatrick, Jacque Lynn Colton, Darby Bricker, David LM McIntyre, Hank Ostendorf, Erika Salomon, Stefanie Zoe Demetriades, Tameé Seidling

PRODUCTION Joel Daavid, scenic director; Leah Piehl, costumes (Kelsey MacKilligan, asst.); James P. Taylor, lights; Andrew Villaverde, sound; Rosey Johnson, hair/wigs/make-up; Christie Wright Gilmore/Christine Breihan, stage management

HISTORY Premiered in Nyack, New York in June 1964 and on Broadway in November 1976, at the Morosco Theatre, with Betsy Palmer and David Selby in the leads. Supported by Elizabeth Redmond

ON THE REAL SIDE Alma's aunt – and namesake – Albertine dies with her lover after he sets fire to his musee mechanique in The Eccentricities of a Nightingale. Today, the most prominent of these odd museums is in San Francisco wharf. See here.

ON THE REEL SIDE View Faye Dunaway's 2001 film of The Yellow Bird, narrated by Tennessee Williams. Part One / Part Two

Jason Dechert and Deborah Puette

Craig Schwartz

Clinical treatment

Though Jane Anderson's The Escort, the "explicit play for discriminating people" premiering at the Geffen Playhouse (through May 8), aims to educate more than titillate, it does manage to have it both ways in Lisa Peterson's frisky staging.

That said, having it both ways doesn't necessarily add up to twice as good. There are mixed messages from this Escort, tolerable with a subject as provocative, pervasive and exploited as sex. No one expects a play that is largely a lesson plan to excel as both art and advocacy. However, a talent like Anderson, who excelled supremely in her last Geffen premiere, the more conventional The Quality of Life, must certainly want to succeed in at least one.

It is also unlikely it would have been any clearer had the playwright directed it herself, as she did with Quality in 2007. Direction, production design and most of the acting fit well with the cool, reasonable approach to the topic. The essential problem is a shaggy point of view woven down into the nap of the play. It begins with a curtain speech that confuses the "voice" of an actress ("I will be playing a sex worker") and her character ("we’ll be portraying my nudity in this way:").

There are big advantages to this opening, however, as it playfully suggests that the playwright has made a conscious effort to de-sensationalize and serve the art. From there, the story, sort-of narrated by Charlotte (Maggie Siff), is her version of an episode involving the three Blooms – divorced doctors Rhona (Polly Draper) and Howard (James Eckhouse), and their 13-year-old son, Lewis (Gabriel Sunday). In frequent direct-address asides to the audience, that cover scene changes, take us into intermission, and send us into the street at the conclusion, she offers a casual, prescriptive infomercial about the health values of high-end prostitution.

According to the first volume of Melissa Hope Ditmore's Encyclopedia of prostitution and sex work:

. . . general agreement among those in the industry is that escort agencies started in the 1960s as "date services." The original agencies catered to men who needed escorts to accompany them to dinner engagements, weddings, corporate affairs, the theater, and so on.

In practice, few escorts get to leave a client's hotel room for dinner or a play. Charlotte is one of these. Brilliant and beautiful, she'll raise a client's standing in public or private. She chose prostitution for the money and like the powerful men she services now commands the highest wages in her field. Charlotte seems above reproach: drug-free, a teetotaler unless a "social" situation demands it, and obsessively hygienic. After her last physician proved too judgmental, she interviews a prospective replacement, Dr. Rhona, to begin the story.

As it turns out, Charlotte also wants Rhona to be her gal-pal. And, over a series of office visits and occasional lunches together, they get close enough for Charlotte to recommend a male escort (Sunday again) to help the neglectful doctor meet her minimal sexual requirements. Though at first Rhona demurs, she later wants the man's name. In one of several moments that equate their mutual professionalism, Charlotte and Bloom stand at center stage, one jotting down an escort's phone number and one writing out a prescription.

The play walks the line between comedy and commentary – grabbing laughs and tugging hearts along the way. The arc follows the women's friendship, which builds until Charlotte's "overworking" by 35 members of an NFL team proves too much for Rhona's tolerance. She finds her judgmental nature – not about morality but self-respect – and ends the friendship.

So, what are we left with? Have Charlotte and all her admonishments for sexual freedom been delegitimized? Unlikely. Has the point of view shifted to Rhona and her husband? They seem equally unworthy of the play's moral high ground after, in an attempt to save young Lewis from Charlotte's clutches, they rat Charlotte out to the police. (A plot point question: Isn't it logical that Charlotte's arrest must have been made in flagrante? If so, isn't her self-congratulations for "saving the life" of her suicidal john a crowning example of self-delusion?)

Which brings us to the beating heart of the real escort here (one who "accompanies a person for protection, guidance, or courtesy"): the play itself. The Escort is a cautionary tale about how people are increasingly disconnected from each other, in part because of the saturation of fantasy and delusion. The sex worker plays only a small part in this slide. The bigger culprit is the encroachment of virtual reality. Overreliance on chat rooms, online games and Internet pornography can replace human interaction in a way that makes prostitution seem positively intimate. Lewis' role in the story is to stress that those in the fog of pubescence could use parents with an escort's openness to what is really going on. Sexual awakening requires much more than simple arousal.

As Charlotte, Siff is superb. The clinical coolness with which Charlotte approaches her work, the guise, the role-playing are there. She embodies that key contradiction of the sex worker, offering unheard of forms of physical intimacy, but unwilling to risk revealing herself in a kiss. The other marvel is Sunday as Lewis and sex worker Matthew. These two aren't just different portrayals. They are different people with visibly distinct backgrounds. Draper is also good, though she is the main victim of the odd perspective problem. And Eckhouse breezes across his dialogue, which is a style the production has throughout. In his case, however, we eventually lose the character. It's telling that his scenes with Draper are the weakest, while those between the others hit hard.

Kudos to Set Designer Richard Hoover for his flexible and always appropriate space, Laura Bauer and Rand Ryan for the costume and lighting design, and Paul James Prendergast for original music and sound.

It's an uphill battle for a serious play that wants to engage in sex education without getting cited for using what it says we abuse. Before the run our gentle media giant panicked like a cartoon elephant when the mousy show art of blow-up dolls appeared in an ad. [Story]). The battle for enlightenment carries on. Anderson, Siff, Peterson and Sunday have taken a respectable step forward.

top of page

THE ESCORT

by JANE ANDERSON

directed by LISA PETERSON

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

March 29 - May 8, 2011

(Opened 4/6, Rev’d 4/16m)

CAST Polly Draper, James Eckhouse, Maggie Siff, Gabriel Sunday

PRODUCTION Richard Hoover, scenic director; Laura Bauer, costumes; Rand Ryan, lights; Paul James Prendergast, sound; James T. McDermott/Jennifer Brienen, stage management

HISTORY Commissioned by the Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; supported through the L.A. County Arts Commission World Premiere

Maggie Siff and James Eckhouse

Michael Lamont

She had a dream

A half-century ago, Lorraine Hansberry turned a pivotal experience in her own life into a landmark in American theater. In a recent revival at the Nate Holden Performing Arts Center, the Ebony Repertory Theatre shows why A Raisin in the Sun remains both testament to social injustice and timeless literature.

The title, taken from Langston Hughes' 1951 Montage of a Dream Deferred, embraces both these functions. Hughes' book-length poem of more than 90 Harlem sketches on the theme of dreams, urged African Americans – as a community and as individuals – to protect and pursue their ambitions.

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore –

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over –

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

The answer would turn out to be "All the above." For Ms. Hansberry, the dream of putting the world she knew on Broadway, where it was unknown, would make her, at 29, the youngest playwright to win a New York Drama Critics Circle Award.

Phylicia Rashad directs with a clear grasp of the subtleties beneath the play's salient points. She grounds the production in realism, beginning with Michael Ganio's functional set, with practical stove, faucets, coffee pot and refrigerator. Ruth E. Carter's costumes, Elizabeth Harper's lights and Bob Blackburn's sound add to the authenticity.

The single set is the two-bedroom apartment in which Walter Lee Younger (Kevin Carroll) and his sister Beneatha (Kenya Alexander) were raised. They still live here, with their widowed mother, Lena (L. Scott Caldwell), and Walter's wife Ruth (Deidre Henry) and son Travis (Brandon David Brown). With the youngest Younger sleeping on the living room couch, a hallway bathroom shared with neighbors, and regular spraying for roaches, they all have their eyes on a better home.

As the play begins, Lena is expecting full payment for her late husband's $10,000 life insurance policy. It will be his legacy, and Lena wants it to go towards Beneatha's medical school tuition and a larger home in a new subdivision. Walter, a private chauffer whose career is a dead-end, has a dream of investing in a liquor store with his friends Willy and Bobo (Ellis E. Williams), and using that money to gain real independence for the family.

Walter's willingness to take on a system stacked against him is contrasted by the future Beneatha chooses. Although she plans to be a doctor, and is offered instant comforts with George Murchison (Jason Dirden), the son of a successful Black businessman, she is drawn to foreign student Joseph Asagai (Amad Jackson), and the chance to leave America with him for the possibility of equality in Nigeria.

Ruth has fewer choices, and as the first act winds down, an impossible "choice" is considered when she discovers another child is on the way. As horrible as it is, give Hansberry credit for having Ruth wrestle with it. Easing Ruth's decision and insuring another grandchild convinces Lena to go with her instincts and buy the larger home..

The challenges to achieving one's dreams presented in the first act, while drawn against the backdrop of social inequality, resonate beyond the African-American story. In the second act, however, the story becomes about racial discrimination – the institutionalized practices Hansberry's father, Carl, battled in court. Karl Lindner (Scott Mosenson), the representative of the Clybourne Park homeowners association, arrives hoping Lena will take back her down payment. Though his offer is righteously rejected, a tragic misjudgment on Walter's part compells the family to reconsider what turns into a profitable buy-out.

Eventually, Raisin will celebrate the power of the individual, the family and the community to rise against injustice. Caldwell is excellent as the matriarch, letting Lena take her time to exert her authority over the family – and the play – before handing it back to a son who earns his place. Walter Lee is an extraordinary opportunity, and although Carroll's is not the definitive performance, there is much to recommend it. Tremendous range and subtlety are required to reveal all the conflicted aspiration and frustrationin Walter Lee Younger. Henry shows the full dimension of a woman trapped within a life that is restricted by confines of her husband's limited opportunities.

The remaining cast are all effective, particularly Alexander as Beneatha, a role that should easily connect with contemporary audiences. Similarly, The somewhat romanticized character of Asagai feels real in Jackson's portrayal. Brown, Mosenson, Dirden, and Ellis all contribute to the quality, as do Quincy O'Neal and Bechir Sylvain, who appear briefly as the movers.

It's worth mentioning that if Hansberry had accurately depicted her childhood experience, it's unlikely that Broadway would have embraced it. What happened to the Hansberrys – and probably lay ahead for the Youngers – was a nightmare. Hansberry's father, a prominent Chicago businessman and political activist (he ran for office as a Republican), was urged to sell a home he bought in the whites-only Washington Park subdivision. He took the homeowners association to court and eventually won (Hansberry v Lee). In her autobiography, To be Young, Gifted and Black, Hansberry described being 8 years old in Washington Park while her father was fighting in court:

That fight also required our family to occupy disputed property in a hellishly hostile ‘white neighborhood’ in which literally howling mobs surrounded our house." My memories of this ‘correct’ way of fighting white supremacy in America include being spat at, cursed and pummeled in the daily trek to and from school. And I also remember my desperate and courageous mother, patrolling our household all night with a loaded German Luger, doggedly guarding her four children.

In the two productions we have attended, ERT has shown it has the vision to take its place among L.A.'s important companies. While Regina Taylor's Crowns was an admirable investment in a problematic script, the production was solid. Here, with a proven classic, the dream of the late Israel Hicks, ERT founding artistic director, is becoming a reality.

top of page

A RAISIN IN THE SUN

by LORRAINE HANSBERRY

directed by PHYLICIA RASHAD

EBONY REPERTORY THEATRE

at the Nate Holden Performing Arts Center

March 23-April 17, 2011

(Opened 4/7, Rev’d 4/15)

CAST Kenya Alexander, Brandon David Brown, L. Scott Caldwell, Kevin Carroll, Jason Dirden, Deidrie Henry, Amad Jackson, Scott Mosenson, Quincy O’Neal, Bechir Sylvain, Ellis E. Williams

PRODUCTION Michael Ganio, scenic director; Ruth E. Carter, costumes; Elizabeth Harper, lights; Bob Blackburn, sound; David Blackwell, stage management

HISTORY Premiered on Broadway in 1958. Supported by Northrup Grumman and US Bank