MARCH 2014

Reviews are on two pages | Click title to jump to review

BILL AND JOAN by Jon Bastian | Sacred Fools Theater Company

CINNAMON GIRL by Velina Hasu Houston | Playwrights Arena

L.A. DELI by Sam Bobrick | Marilyn Monroe Theatre

PAUL ROBESON by Phillip Hayes Dean | Ebony Repertory Theatre

THE PIANIST OF WILLESDEN LANE by Mona Golabek | Geffen Playhouse

REUNION by Mona Golabek | South Coast Repertory

TARTUFFE by Moliére | A Noise Within

TOP GIRLS by Caryl Churchill | Antaeus Theatre Company

Shot up

More than 20 years ago, when Jon Bastian was beginning his playwriting career, he started a script on writer William S. Burroughs. Sensing that his skills needed to catch up with his ambitions, he backburner'd Burroughs and pursued other projects, including Noah Johnson Had a Whore . . ., which premiered in 1992 at the theater where I did publicity. Two decades of play fermentation and playwright maturation ended in February when Bill and Joan took the stage at L.A.'s Sacred Fools Theater Company.

The delay meant that Bill and Joan's mounting now marked the centennial of Burroughs' birth, on February 5. More importantly, it meant that director Diana Wyenn, in grade school when Bastian began, was available to give the production the continual sense of restless invention that bubbles beneath the Spartan staging and makes it such a success.

The history of Burroughs and his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer, climaxed in Mexico City in September 1951. In a festive atmosphere blurred by heroin, Benzedrine, and alcohol excess, Bill and Joan, an important Beat-generation figure in her own right, played a game of "William Tell." Based on the fictional bowman's legendary shooting of an apple off his son's head, Burroughs, a gun enthusiast and practiced marksman, targeted the highball glass atop Joan's head. Aiming low, he hit the head instead.

The play begins the next day, with Burroughs (Curt Bonnem, a reasonable vocal and visual facsimilie) awaiting interrogation by local detectives (Richard Azurdia and Alexander Matute). He sits repeating "Nothing is true, everything is permitted," a favorite maxim by an 11th Century religious agitator in Persia. Hassan I Sabbah lived up to the maxim, one Burroughs biographer wrote, by "recruiting political assassins who were fed hashish for motivation."

What's true and what's permissable blur beautifully in Bastian's and Wyenn's vision. Though Burroughs is useless recounting the previous evening's events, the interrogation prompts shards of historical flashback and hallucinatory flurries that blend his fictional writing with facts about his life with Vollmer (an impressive Betsy Moore). The rest of Wyenn's ensemble (Lauren Campedelli, Donnelle Fuller, Will McMichael, Bart Tancredi, and Scot Shamblin in for regular Matt Valle) create Burroughs' confidants – real and imagined. Among them, the revelation is Fuller, who, in what could produce a collective audience eye-roll, creates a riveting embodiment of heroin's alternating hunger and bliss.

If there is a dead zone in Bastian's work it is in the loggerheads that he quickly reaches in the interrogation room. The addled Burroughs obviously can't remember what happened and, as good as Azurdia is, the lead detective hits high frustration early and has nowhere to go. Eventually the second detective provides some character dimension and an avenue out of the dramatic stalemate.

Along with the strong showings of Bonnem, Moore, and Fuller, a quick appreciation for McMichael's fight direction on a handful of upstage slaps and punches. Every one comes out of the blue, cracks with a perfectly timed smack, and sends the recipient reeling. It may be a benefit of seeing the show at the end of its run, and perhaps Wyenn's choreographer chops helped, but it nevertheless bears the stamp perfectionists, and is appreciated.

Wyenn, who takes "production design" credits, designed an abstracted interrogation room set surrounded by stacked panels of lights with drip-pan reflectors. Matt Richter and Christina Robinson's light cues provide enough variation to establish the various moods and locales. Druggies who've been face-down for a stovetop light and eyebrow singe will feel right at home with the double-meaning drip-pans.

It may not be clear that, although Burroughs was a charter member of the Beat writers who gathered at Vollmer's New York City home in the 1940s, along with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, he disdained writing at first. Kerouac's On The Road had been written months before Joan's death, but Burrough's first published novel, Junky, would not be out until after the infamous, and clearly cathartic, episode in Mexico City.

top of page

BILL AND JOAN

by JON BASTIAN

directed by DIANE WYENN

SACRED FOOLS THEATER COMPANY

January 24-March 1, 2014

(Opened 1/24, Rev’d 2/28)

CAST Richard Azurdia, Curt Bonnem, Lauren Campedelli, Donnelle Fuller, Alexander Matute, Will McMichael, Betsy Moore, Bart Tancredi, Scot Shamblin (in for Matt Valle), u/s Dana DeRuyck, Rick Steadman

PRODUCTION Diana Wyenn, production designer; Lauren Oppelt, costumes; Matt Richter/Christina Robinson, lights; Mark Corben/Chet Leonard, sound; John Burton, effects; Will McMichael, fights; Rebecca Schoenberg, stage management

HISTORY Produced by David Mayes

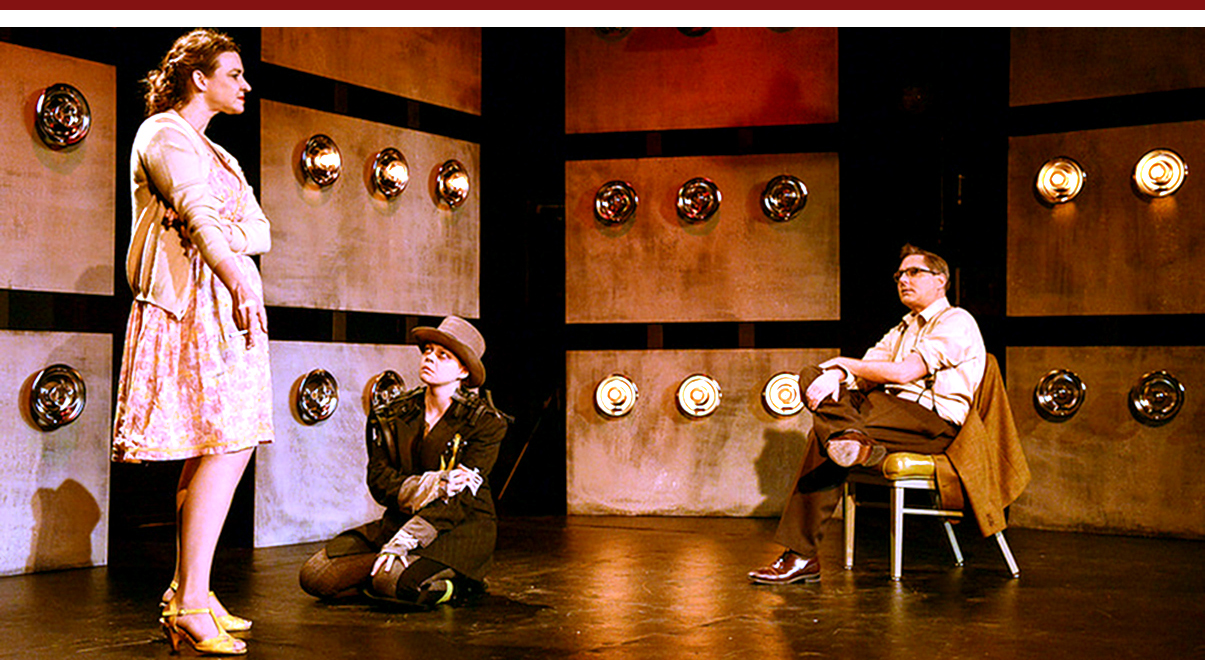

Betsy Moore, Donnelle Fuller, and Curt Bonnem

Jessica Sherman

Keys to the past

The Geffen Playhouse's long-standing relationship with storytelling musician Hershey Felder, who portrayed such famed pianists as Beethoven, Liszt, and Chopin at the theater, took a turn in 2012 when he brought them the story of Lisa Jura, a relatively little-known child prodigy born in 1924 Vienna. She was the subject of The Children of Willesden Lane, a book by Mona Golabek and Lee Cohen.

Unlike Hershey's scholarly impersonations of music's greatest historical figures, the one-woman show The Pianist of Willesden Lane would be personal and intimate. Golabek, a concert pianist, would play the character and favorite pieces of Jura, who was her mother. The premiere in April 2012, on the Geffen's smaller stage, was so well received that it went on to success across the country. Earlier this year, when the Geffen's planned revival of The Birthday Party blew up in rehearsals, Golabek was available to mount Willesden in a limited run on its larger stage. The ticket demand required an extension before the show had opened.

At the front of a stage, before a gleaming Steinway that stretches below four large, empty picture frames, Golabek briefly welcomes us and introduces the subject of the performance. This was her mother, which tells us that whatever happens to little Lisa over the 95-minute, intermission-less performance, she will survive.

She then moves to the piano bench, going back in time to 1938 Vienna, and back in age to become the 14-year-old piano student as she is told by her tearful teacher that he would risk his life to continue instructing – or even having in his home –a Jewish child. Now through her innocent eyes we share Lisa's reticent awakening to the hate-fueled war crimes that her government has planned for her family and community. Following the attacks of kristallnacht, on November 9, 1938, Lisa's parents insist that she use their only ticket on the government-sanctioned Kindertransport, and flee to England. Her mother explains why she, rather than either of her two sisters, was chosen. Because of her extraordinary talent, she will represent her family and touch the lives of people with her beautiful music.

Lisa arrives in Britain only to be left on the dock by the family member who had agreed to meet her. He has arranged for the relocation organization to come for her. That begins several episodes in bomb-shaken residencies filled with children and colorful hosts worthy of Dickens. At Willesden Lane she discovers a piano has survived – apparently in tune – in the basement. There she is able to practice away, dedicating herself to someday debut and earn music school entry. Meanwhile, Golabek and Felder's adaptation keep us well aware of the progressing World War. When it ends, we follow Lisa as her career, and then family-building take her to America.

Though not trained in theater, Golabek's presentation is pleasingly straightforward. Felder, who also directs, keeps the material and the music at the forefront. Felder, who designed the set with Trevor Hay, uses a similar format to his recent Lincoln story, another break from his composer series [reviewed here]. Those picture frames will hold newsreel footage of Nazi movements as well as faces of family members now gone.

Along with the great musicianship Golabek clearly inherited from her mother, she has borne the promise of carrying on outreach to future audiences. Though Lisa died in 1997, she returns in her daughter's play and playing. The excerpts from pieces she cherished are beautifully sprinkled through the show, but Golabek saves her power and passion for the concert-quality finale, which after an hour and a half of storytelling and piano playing leaves here visibly spent.

The Pianist of Willesden Lane is one more reminder that soon there will be no first-person witnesses to World War II and the Holocaust, a generation later there will be no one who heard the direct account of someone who was there. Some, like the Juras, who could put only one daughter on the train that represented the legacy they wished for the future, would be happy to know that their music–and story–endures.

top of page

THE PIANIST OF

WILLESDEN LANE

based on the book 'The Children of Willesden Lane' by MONA GOLABEK & LEE COHEN

adapted and directed by HERSHEY FELDER

GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE

February 28-March 9, 2014 (extended to 3/19)

(Opened 2/28, Rev’d 3/1 mat)

CAST Mona Golabek

PRODUCTION Trevor Hay & Hershey Felder, set; Jaclyn Maduff, costumes; Christopher Rynne, lights; Erik Cartensen, sound; Andrew Wilder & Greg Sowizdrzal, projections; Young Ji, stage management

HISTORY Eighty Eight Entertainment, Samantha F. Voxakis, and Robert F. Birmingham, producers; presented by Hershey Felder and the Geffen Playhouse

Mona Golabek

Michael Lamont

Staying tight

High school and the first act of a play both end with many opportunities to pursue after taking a break. Reunion, Gregory S Moss's new play about three former friends reuniting 25 years after graduation, is a somber look at growing old, growing apart, and the dangers of trying to reclaim old glories. There is the distinct impression, however, that characters and play have squandered their second act potential.

The South Coast Repertory premiere (through March 30) follows what must have been a promising public reading at the theater's 2013 Pacific Playwrights Festival. Again like its characters, the full production, with Adrienne Campbell-Holt back as director, indulges in excesses that limit what it has to say.

The play takes place in a motel near the suburban Boston high school, immediately after the official event. It's around midnight when Peter (Kevin Berntson) and Max (Michael Gladis) arrive. They have moved far enough away to require air travel here and Max can only stay an hour if he is going to be rested for an early flight. Peter, however, expects the kind of all-night blowout that cemented this unique friendship. When he's not checking in with his wife Judy, another classmate who stayed home with their sick baby, he is trying to get Max excited. He shares phone-photos of his kids and what little he knows about yet-to-arrive Mitch (Tim Cummings), who chose this motel room, the scene of one of their major get-togethers, for their post-reunion reunion.

Moss has prepped us for Mitch's entrance and Cummings doesn't disappoint. He immediately commandeers the room and establishes himself as the alpha male. When Max mentions leaving and explains he's on the wagon, Mitch goes into attack mode and sends Pete for whiskey. As soon as Pete is gone, Mitch pulls a bottle from his bag along with a bizarre-yet-beautifully metaphoric relic from the past. It's one of Moss' finer moments and we wish he had come up with more of them. It's quickly back to Mitch's bullying, however, and Max topples off his wagon, setting the stage for a second act of full throttle abandon.

Like the present Mitch unearths for Max, there are secrets that have been buried. While Mitch and Max reveal hurtful stories about Pete's wife , they guard their own secret, that big event that occurred in the motel room, until the bitter end. It will take a lot of alcohol, drugs, heavy metal air guitar and most of the second act to get there. The addition of an intermission into a 97-minute play suggests itwas to accommodate the stage reset for party damage. SCR has indulged the writer and director the production support to recreate drug-induced mayhem. But it's a narrative dead zone, and audiences may feel like designated drivers waiting for their friends to finally hit the wall. The characters do hit the wall, literally, tearing into the side of Sibyl Wickersheimer's set, in which she carefully reveals that the room is well insulated.

Campbell-Holt has cast three strong performers here. Berntson is memorable as shallow third-wheel Peter. Gladis begins as a muted Max whose letting loose is volcanic. As Mitch, Cummings is a fierce force of nature. After the extended partying he shows his deep hurt without relinquishing his dominance. He plows through the occasional purple prose Moss has given him and nearly makes it sound convincing.

Stephanie Kerley Schwartz's costumes are perfectly suited to the group, with Mitch's bright ruffled shirt a nice signal of his ill-fitting role as the group's ladies man. Having the dust from one of Pete's Pixy Stix stick to Mitch's face like war paint is a great touch, too. Elizabeth Harper's light cues, while spot on, seem to suffer the same excesses as the production in general. They seem to be constantly readjusting to focus our attention. If only the writing were sufficient to provide better highlighting. M.L. Dogg, the successful sound designer on the Geffen's Rapture Blister Burn, can't be faulted for giving the production what it wants, while Edgar Landa's fight choreography serves the action well.

Props to the P.A.s and backstage crew who have to clean up the mess after each show. The beating Wickersheimer's set takes is worthy of a Keith Moon rampage during the Who tour for Who's Next. For the record, however, this one is more likely to be filed under Who Cares?

top of page

REUNION

by GREGORY S MOSS

directed by ADRIENNE CAMPBELL-HOLT

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

March 9-30, 2014

(Opened 3/14, Rev’d 3/15m)

CAST Kevin Berntson, Michael Gladis, Tim Cummings

PRODUCTION Sibyl Wickersheimer, set; Stephanie Kerley Schwartz, costumes; Elizabeth Harper, lights; M.L. Dogg, sound; Edgar Landa, fights; Kathryn Davies, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Tim Cummings, Michael Gladis, and Kevin Berntson

Ben Horak

Cloudy spectacles

Franco-American relations have had their ups and downs, but poet Richard Wilbur's translations of Moliere's French-language plays are always a source of mutual pride. Three hundred years after Tartuffe's 1664 Paris debut, Wilbur, who turns 93 on March 1, adapted it for Americans. A half-century later, it launches the second half of A Noise Within's 2013-14 Season. Directed by co-founder and co-artistic director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott, the production's capable cast lets the author's rhythmic, rhyming couplets clearly sound their warning once more.

The staging suggests efforts at a unifying concept, but these are only occasional flourishes that do not tie together and, despite generally appealing performances, fail to create a sum-is-greater-than-the-parts distinction.

Tartuffe, subtitled "The Imposter," follows Orgon (Geoff Elliott), a devout man of means who is hoodwinked by a religious charlatan, Tartuffe (Freddy Douglas), into giving him his heart, his home, and his daughter's hand. His entire household, except for his pious mother, Madame Pernelle (Jane Macfie), sees through Tartuffe's fraud but are unable to open his eyes until it is almost too late.

The production's shortcomings begin with Frederica Nascimento's set. While the classic white, black, and red palette might suggest the homeowner disdains, or just cannot recognize, gray areas, a loud wallpaper so dominates the upstage wall that Angela Balogh Calin's resplendent period costumes, along with the actors wearing them are fighting it to be seen. Lighting Designer Ken Booth does what he can to separate the combatants until a massive portrait covers the wall in act two. There's also a confusing beam structure beyond that wall that might be a building going up, coming down, or just scaffolding that permits Tartuffe to stand high above the set.

We have plenty of time to view the set during a langourously paced opening. Characters gather slowly, lounging in the wake of a party as the maid, Dorine (Deborah Strang), cleans up. It is meant to be what provokes Madame Pernelle's lecture about abiding Tartuffe and the example he sets. The "sin" she references is probably only separation from God, which is enough for the play. Rodriguez-Elliott hints at licentiousness, which would probably not be tolerated by Orgon.

The few anachronisms that are occasionally inserted also fail to connect. Modern glasses worn by Orgon and his son, Damis (Mark Jacobson), offer a metahor of having, losing, or requiring good vision. But why pair Orgon and Damis with spectacles? One is blind to Tartuffe's facade while the other sees through it? And, when the Officer (William Dennis Hunt) of the King arrives to arrest Tartuffe, he delivers his address as a lounge entertainer with microphone, disco ball, microphone, and fan dancers. Is this a critique of the Catholicism of Louis XIV, who at the time the play premiered was 26 and thought by many a divine gift of God? Or is it just a lively musical number with which to close the show?

For the most part, the cast keeps things moving, and never allow the cadence of the dialogue to get "singsongy." Although too young for the role, Macfie is especially good, as are Alison Elliott as daughter Marianne and Rafael Goldstein as her chosen, Valère. Their scenes together strike the right balance of silliness and significance.

The always-solid Strang, the debuting Carolyn Ratteray as wife Elmire, and the elder Elliott all allow Molière's Wilburized wording to find naturalness. As Tartuffe, Douglas, a consistent favorite in these pages, delivers his lines with the measured articulation of the late Peter O'Toole. It is a delightful performance, and When he appears, draped in white, as the lone diner in a mock Last Supper tableau, it's easy to recall The Ruling Class, the film adapted from Peter Barnes' play of similar tone.

Unfortunately, Douglas' wonderful portrayal does not penetrate very deep and midway through act two we see this Tartuffe is little more than a one-dimensional cad under a false veneer without the dimension to respond to his sudden change of fortune. There is room for more here, and likewise in the way co-founder Elliott, the company's go-to leading man, has chosen to keep Orgon a simple-minded comic foil. This production tilts towards the slapdash and silly.

There originally was enough skewering of religious folly in this play when it premiered to have caused it banned until rewrites were made. Even rewritten, however, it still has room for greater layering. Orgon, who embodies that fundamental demand of true faith, which is that a believer hold to his convictions despite earthly evidence to the contrary, is just doing as he believes he's been told. He can logically assume that if someone presents himself as a man of God, it is with God's blessing. Otherwise, what the Hell is He doing with His will?

top of page

TARTUFFE

by MOLÈRE

adapted by RICHARD WILBUR

directed by JULIA RODRIGUEZ-ELLIOTT

A NOISE WITHIN

February 15-May 24, 2014

Opened 2/22, rev’d 2/23m

CAST Freddy Douglas, Alison Elliott, Geoff Elliott, Rafael Goldstein, William Dennis Hunt, Mark Jacobson, Jane Macfie, Carolyn Ratteray, Stephen Rockwell, and Deborah Strang, with Erin McDonnell, Saundra Montijo, Catlin Parks, Elizabeth Parmenter, Madeline Russell

PRODUCTION Frederica Nascimento, set; Angela Balogh Calin, costumes; Ken Booth, lights; Robert Oriol, music; Emily Lehrer, sound; Caity Hawksley, hair/wigs/makeup; Julana McBride, stage management