DOWN FOR THE COUNT

Direction to Eugene O'Neill's Monte Cristo home and childhood

by CRISTOFER GROSS

Between June 28 and July 12, 2008, some aspiring theater critics gathered in Waterford, Connecticut for the annual National Critics Institute, a ‘boot camp’ for working writers interested in reviewing theater. The two-week program sits in the middle of the O’Neill’s six-week musical and play development festival at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, a cluster of century-old structures that house theaters, offices, meeting rooms, residences and a bubbling watering hole named Blue Gene's.

The complex is located a short drive from Monte Cristo, Eugene O'Neill's boyhood home. Six years ago, I was part of the nine-member Class of 2008, which marked the NCI’s 40th Anniversary. We ranged in age from 23 to 55 and in point-of-origin from Vermont to California.

I had come the farthest, by either measure.

It is no exaggeration to say that within 24 hours of arriving on campus, we had penetrated deep into the heart of American drama.

Our first morning, July 8, was to be spent getting the stage director’s perspective on theater productions from J Ranelli, a previous Interim Executive Director at the O’Neill. His classroom would be Monte Cristo Cottage, Eugene O’Neill’s boyhood summer home and the setting for both Ah, Wilderness, his only comedy, and Long Day’s Journey Into Night, a searing autobiographical exposé.

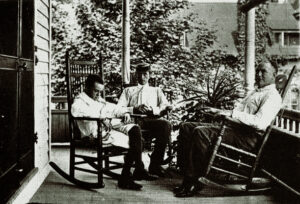

The two-story New London cottage, a few miles east of Waterford, still has the wide porch that young O’Neill looked from a century ago. The hedge he would have seen (the one Edmund and his father trim in Journey) still grows at the bottom of the raked front yard. Beyond it, across narrow Pequot Avenue, are more old homes and Connecticut’s Thames River.

The O’Neills sold the house in the 1920s. Two subsequent owners made no substantial renovations over the ensuing half-century, and in 1971 it was declared an Historic Landmark. Three years later it was purchased by the O’Neill Theater Center and used for meetings and a library for scholars and artists to read O’Neill documents in the rooms where he once read. In 2005 it was opened to the public for tours and study.

Ranelli was alone in the house when we arrived and greeted us like its proud custodian. He led us to a small, paneled sitting room where windows on three sides blazed with morning light. We gathered folding chairs around a center table and opened our copies of Long Day’s Journey to where O’Neill gave instructions on how a production's set should look. The stage directions were extremely detailed, which seemed odd for a play his will stipulated could never be performed, only read, and then not before he had been dead for 25 years.

As it turned out, only three years after his death in 1953, his widow, Carlotta O’Neill, who had received the play as an anniversary present, sanctioned its production in Sweden, New Haven, and New York. The impact was extraordinary. José Quintero’s Broadway staging earned O’Neill a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1957 and set off a string of revivals that re-established him as a founding father of American dramatic literature.

O’Neill’s father, James, had purchased the home when he was a superstar of the American stage in the latter 1800s. In the 1870s, his acting was so respected that Edwin Booth, considered the greatest American actor of that century, alternated lead roles with him in a production of Othello. According to O’Neill: Life with Monte Cristo by Arthur and Barbara Gelb, that was "a ritual only followed, as a rule, when two stars of equal fame occupied the same stage together."

By the time Eugene was a boy, however, James’ fear of poverty, love of popularity, or both had reduced his repertoire to a single, money-raking role: The Count of Monte Cristo. For years, he accompanied his father on his tours across the country, watching the same show, night after night from the wings.

Eventually, normal teenage resentment for a parent grew into a maturing writer’s resentment of a great talent squandered on hollow mass entertainment. It sent the son into diametric opposition, writing plays that explored what people really experienced. If in the process they exposed his father's folly, so much the better.

ln a very real way the birth of true American drama at the dawn of the 20th Century was happening in this one family. O’Neill’s writing, which would provide our nation’s first authentic stage literature, would be as much in response to his father as to the art he represented. Two generations of one family would literally straddle the divide over a dinner table, arguing or fuming in silence in a room that became the crucible of American drama.

And on this sunny morning in summer 2008, we nine critics in training were in that room, around that table.

As we read Journey’s stage directions aloud, a sentence each in turn, Ranelli occasionally had us stop and look around the room. It was an exact match, down to the book titles.

Ranelli wanted us to hear a section of the text and picked the group’s oldest male to read the part of James Tyrone, the character based on James O’Neill, and a DC-area freelance writer with acting experience to read Mary Tyrone, based on his mother. We worked through the opening pages several times, stopping repeatedly as Ranelli led the group on a search for more nuance to work in our performance.

Zev Valancy and Scott McCarrey, two writers in their 20s with plenty of fresh stage experience (McCarrey had recently performed Shakespeare in England), had been assigned the parts of the Tyrone sons. Ranelli had them make their entrance from the actual adjacent room that O’Neill had in mind. They arrived in a cloud of laughter that caused their father, assuming they were laughing at him, to react to with anger. They bounded in, once more filling the old house with youthful energy.

I read James’s lines, hiding my resentment for the wife and sons I was sure were conspiring against me, and as the words came out of my mouth I felt the old sitting room stirring around us. Ranelli had re-animated the spirits of this pivotal theater family in the very site of American drama’s ‘big bang.'

And, for just a moment, I wasn't a neophyte critic reading from the American theater’s Book of Genesis. I was home with my family on New London’s Pequot Avenue, both father and star of stage. And they were going to show me respect.