APRIL 2014

Click title to jump to review

FIVE MILE LAKE by Rachel Bonds | South Coast Repertory

THE PURPLE LIGHTS OF JOPPA ILLINOIS by Adam Rapp | South Coast Repertory

REST by Samuel D. Hunter | South Coast Repertory

THE TALLEST TREE IN THE FOREST by Daniel Beaty | Mark Taper Forum

Appreciable

At different points in Five Mile Lake, Rachel Bonds' polished and probing new drama about closing the gap between wish and fulfillment, two brothers tell the same woman how satisfying it is to watch someone "really good at what they do." I got that same feeling while watching the world premiere of Bonds' play at South Coast Repertory (through May 4).

The craft at work here doesn't call attention to itself. It is an exercise gracefully free of artifice in which characters develop and secrets reveal naturally. It's beneath the natural lines of dialogue that Bonds' writing is propelling the action like some muscular swimmer, only breaking the surface to take a breath between the well-shaped scenes.

Director Daniela Topol's staging complements the tone and pace. Her five actors are so suited to their roles they could have come with cutouts designer David Kay Mickelsen found to ensure authenticity for the costumes. Set Designer Marion Williams and SCR's production department have woven a physical and aural environment from woods, hues, sounds, and light that suggest the remote area of the title. Lap Chi Chu is Lighting Designer; Vincent Olivieri provides music and sound design. Palettes slide the set pieces on and off for minimal disturbance.

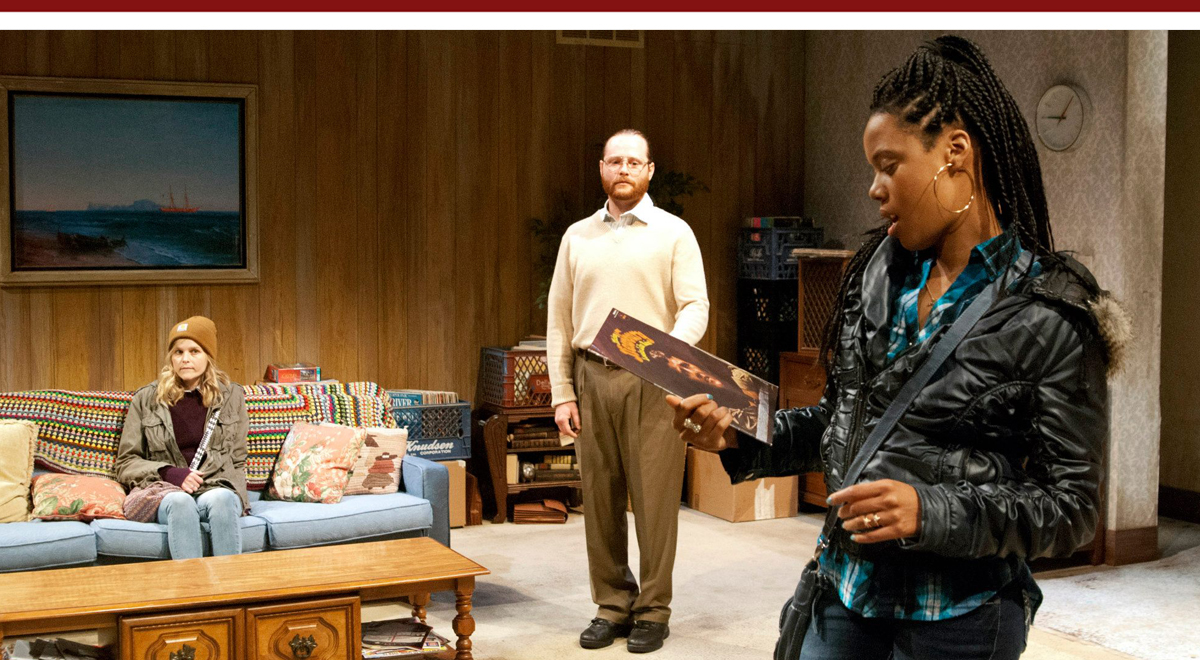

The two brothers are Jamie (Nate Mooney) and his older brother Rufus (Corey Brill). They grew up in the isolated community at Five Mile Lake, near Scranton, Pennsylvania. It is winter. When Jamie is not working at the bakery coffee shop he is visiting their infirmed mother, watching hockey, and patching up the family's dilapidated lake house. Rufus, who dove into academia years ago to escape the lakeside world, has returned unexpectedly with longtime girlfriend Peta (Nicole Shalhoub) in hopes of patching up a relationship he has undermined with neglect. Jamie's co-worker is Mary (Rebecca Mozo), the younger sister of Rufus' high school pal Danny (Brian Slaten), back from fighting in Afghanistan and having trouble getting on track.

It is Mary to whom the brothers separately share their appreciation of people who know they are doing. But there is a key difference. Just as there are two ways to get across a lake – the runaround or the plunge – Jamie and Rufus approach Mary in ways that reveal their manners, goals, and problems. An unspoken infatuation for Mary has bottlenecked Jamie and he repeatedly tries to convince her of the skill displayed by hockey players, whom Mary openly disdains. He is so far from addressing his desires, it's as if his subconscious has stepped in, testing her willingness to reassess people she has dismissed as uninteresting.

By contrast, Rufus, with con man charisma and the ease of the otherwise committed, is direct. He is talking about Mary and the late night highway runs he recalls seeing when he lived in town. His open appreciation earns her confidence, and she tells about her feelings and frustrations. This seemingly simple message of openness and honesty is nevertheless ignored by most of us, and will be what each character needs to regain or develop their potential. In a lovely frieze to end the show, Topol and Bonds suggest the benefits.

Mooney, Shalhoub and Slaten make impressive SCR debuts. Mooney's Jamie is earnest and a believably overshadowed younger brother who needs assurance before taking romantic risk. His jealous brusqueness, after seeing the ease with which Mary and Rufus connect, comes from longtime hurt. Shalhoub, a British immigrant born of immigrants to England, provides an organic portrait of someone making it in America but losing it with her American. Slaten's modulated performance includes telltale explosiveness at what he feels is his sister's nagging.

Brill is back following a completely different assignment as Mr. Darcy in SCR's Pride and Prejudice a couple years ago. Here he is a perfect fit as the self-proclaimed genius. Mozo continues to do the kind of outstanding work that just made Antaeus' Top Girls (review) a top pick, and earned her an award for last year's Mrs. Warren's Profession (review), at the same theater.

top of page

FIVE MILE LAKE

by RACHEL BONDS

directed by DANIELLA TOPOL

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

April 13-May 4, 2014

(Opened 4/18, Rev’d 4/23)

CAST Corey Brill, Nate Mooney, Rebecca Mozo, Brian Slaten, Nicole Shalhoub

PRODUCTION Marion Williams, set; David Kay Mickelsen, costumes; Lap Chi Chu, lights; Vincent Olivieri, music/sound; Jennifer Ellen Butler, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Rebecca Mozo and Nate Mooney | Debora Robinson

The purple lights of illness

Years ago, party directions led me to the rolling hills and nodding oil pumps of Signal Hill. Under the city's amber streetlamps, the cars, trees, and buildings glowed orange as if seen through special goggles. In Adam Rapp's new play about reconnecting, lights may be playing tricks on one character as he struggles to find his way.

The Purple Lights of Joppa Illinois is part of South Coast Repertory's 2014 Pacific Playwrights Festival, and it continues (with Rachel Bonds' Five Mile Lake [REVIEW]) through May 4. Ellis Shook (William Apps) is in a twilight world of his own. He suffers from a "bipolar affective disorder, with psychosis," which produces tremendous anxiety. Without the prescribed Lithium he has paranoid hallucinations.

Alone in his apartment, Ellis stands nervously. His tidy ponytail and trim beard, and the sweater he tucks into his slacks suggest he's wrapped a little too tight. A phone call informs him visitors will arrive soon and he launches a manic final flurry of preparations, swathing a roll-on and cueing up some raging hip hop. He calms in time to admit the two teenage girls knocking on the door.

Rapp often populates his plays with folks coping with some form of estrangement. Their language may be defensive, but there is self-knowledge in it, and its humor and heart invites us to get closer. He knows this territory from a childhood living with his divorced mother and siblings in Illinois, and has returned to it in quietly affecting films like Winter Passing, with Zooey Deschanel, Will Ferrell, and Ed Harris, has used it for an intricate storyline on HBO's In Treatment (in which a Bengali widower manages to get himself deported back home), and in numerous plays including his Pulitzer finalist Red Light Winter.

Gradually we learn Ellis' story. Twelve years ago, his unpredictable emotions caused him to separate himself from his wife, and nine-month old daughter. Unfortunately, he did not get treatment until it was required following a violent hallucinatory episode. After incarceration and institutionalization, he is now free to live and work within a 12-mile radius monitored by an ankle bracelet. He lives in Kentucky, across the Ohio River from his ex-wife and daughter Catherine, now 13, in Joppa.

One floor lamp is especially troublesome for Ellis, who accuses guests of moving it. More mysterious are those purple lights, which are never referenced in the play. He does tell Catherine (Virginia Veale), that he often sits and watches the lights of a refinery in Joppaa from a hillside overlooking the river. Perhaps they appear purple to him, and hopefully that is a comforting.

With the aid of Facebook and his visiting nurse, Barrett (Connor Barrett), Ellis has begun chatting with Catherine online. Today, accompanied by an older friend named Monique (Christina Elmore), she has arranged a reunion without telling her mother.

Director Crispin Whittell has given the play an atmosphere of apprehension and optimism. There is a sense of imminent danager, and we are so rapt that an entire, five-minute album track can be played and we're fascinated to watch the characters as they listen. Apps is effective as a man self-sentenced to a life of contrition and apology. He yearns for forgiveness yet is the first person to admit he probably doesn't deserve it. Elmore's Monique is full of anger and aggression leavened by her frequent displays of high-IQ linguistics. Stealing the show and our hearts is Veale's Catherine, an innocent prematurely shoved into adulthood who endears herself with her bravery and those vestiges of childhood she thinks she has shaken off. Barrett has the least flashy role, but keeps it interesting.

After the wonderfully disorienting opening scene, Purple Lights settles iin as a straightforward play about people trying to reconnect despite odds stacked against them. It carries an understanding that with mental illness, the perpetrator of violence is also one of the victims.

This third concurrent festival production is new for SCR, and Sara Ryung Clement has provided a complete environment with scenic design and costumes, while Adam J. Frank's lights are nicely complementary. Sound designer Corinne Carrillo has had fun with the eclectic tune selection, and stage manager Ashley Boehne Ehlers calls the show from the booth.

top of page

THE PURPLE

LIGHTS OF

JOPPA ILLINOIS

by ADAM RAPP

directed by CRISPIN WHITTELL

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

April 24-27, 2014

(Opened 4/24, Rev’d 4/26m)

PRODUCTION Sara Ryung Clement, set/costumes; Adam J. Frank, lights; Corinne Carrillo, sound; Ashley Boehne Ehlers, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere

Virginia Veale, William Apps and Christina Elmore | Ben Horak

Diminishment

Seven characters – three over 80 and the rest under 40 – are snowbound in a senior care facility. Those with years ahead of them tend to the others as the facility itself is in its final days. Martin Benson directs the commissioned South Coast Repertory premiere (through April 27), as he did Hunter's The Whale (review) a year ago.

While the psychological implosion of The Whale's central character held the other characters in orbit, that gravitational pull is missing from the core of Rest. We are again in Hunter's place of origin, Northern Idaho. The script suggests a dutiful sense of capturing his homeland zeitgeist. But for those of us who don't know or care about it, something feels absent. The characters float in their own self-interest without the investment in anything to create much conflict or dramatic engagement.

This may be part of a motif Hunter signals in references to modern Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, whose music, which approached the eternal through minimal "tintinnabulation" (bell-like tones) and use of silent space, is heard on two occasions. Pärt's body of work inspired one reviewer to write, "How we live depends on our relationship with death; how we make music depends on our relationship with silence."

One of the title's meanings is the musical rest, or silence. It is mentioned in the eighth and final scene, which, like an octave scale reaching its apex cycles back to the opening tone, reuniting two characters to repeat a line of dialogue they shared. When one of them says "I can't hear the music," the play reaches its end.

Resident Etta (Lynn Milgrim) has for 12 years held fast to her husband, Dr. Gerald Erikson (Richard Doyle) through his spiraling slide into dementia. Tom (Hal Landon Jr.), a widower with a calm stoicism regarding his circumstances, is the only other patient out of the 70 who lived there until recently, when it was sold. In the second scene we learn that Gerald again has wandered off, but this time he could die in the cold. Roads have closed and no emergency vehicles can help. Here where death is just another resident, staff are concerned but not alarmed enough to go outside and look for him.

With Gerald's disappearance, the play's most interesting character (even in dementia) is gone and our focus shifts to the less-compelling staff. There is the bumbling chief administrator, Jeremy (Rob Nagle), who took over two years ago after fleeing New Mexico when divorce ended an eight-month Match.com marriage. Just-hired cook Ken (Wyatt Fenner), a mildly evangelical Christian, is hysterically afraid of both death and the dark. And nurses Ginny (Libby West) and Faye (Sue Cremin), friends from high school, are four months into a surrogacy arrangement they are each secretly questioning. The quartet adds their respective themes to the piece: career competency, motherhood, marriage, and religious faith.

It's best not to spoil what happens. Suffice to say, the effects are strangely muted in a play that seems to proceed at such an even keel. Benson has done the right thing in not pushing for dramatic emphasis. True to the theater's age-old tenets, it lets the writing do its work.

They have a great ally in Milgrim, whose Etta is worn by years of painfully pointless interaction with the shell of her husband, yet continues to offer him kindness and encouragement. That mix of optimism and weariness carries into her conversation with the staff, where the weariness generally wins out. Landon's Tom is another treat. Weathered by loss, he stands as dominant sage when the others need to focus on what's important. Yet, he is childlike and dependent when awaiting his dinner.

Nagle works a little too hard to make Jeremy the comic relief. In fairness, it's in the script and given the play's generally planar topography, it must have seemed a good idea. Fenner, who served a similar function as the mildly evangelical Morman missionary in The Whale, is such a perfect fit here that it's likely Hunter wrote it with him in mind. West and Cremin are fine actors who do their best to make the younger women interesting.

John Iacavelli creates a set with the right institutional lack of imagination. We feel the encroachment of neglect as the facility is in the final stages of its life. Angela Calin Balogh gives the play costumes that are remarkably unremarkable. Milgrim and Landon's old-folkswear is hauntingly familiar. Donna Ruzika is expert at just the right levels to make the lighting feel fluorescent without it being so, or candle-powered when we shift to a scene during a power outage. And, with a play with a quiet, if considered compositional component, Michael Roth serves the production well.

Finally, it is Doyle, with the least amount of stage time, who gives the play its footing. The root of a musical scale is where we land for resolution, where a passage finds resolution during the lifelike cycles of tension and release. Even in absentia, his part is the heart of the play's message of the tragedy of this kind of loss. He and Milgrim give Rest its resonance.

top of page

REST

by SAMUEL D. HUNTER

directed by MARTIN BENSON

SOUTH COAST REPERTORY

April 10-September 30, 2012

Opened 6/29, rev’d 4/13m

CAST Sue Cremin, Richard Doyle, Wyatt Fenner, Hal Landon Jr., Lynn Milgrim, Rob Nagle, Libby West

PRODUCTION Ralph Funicello, set; Deirdre Clancy, costumes; Alan Burrett, lights; Lindsay Jones, sound; Shaun Davey, music; Steve Rankin, fights; Elan McMahan, music direction; Christine Adaire, vocal/dialect; Bret Torbeck, stage management

Hal Landon Jr., Rob Nagle, Lynn Milgrim, Libby West, Sue Cremin and Wyatt Fenner | Debora Robinson

Unbowed

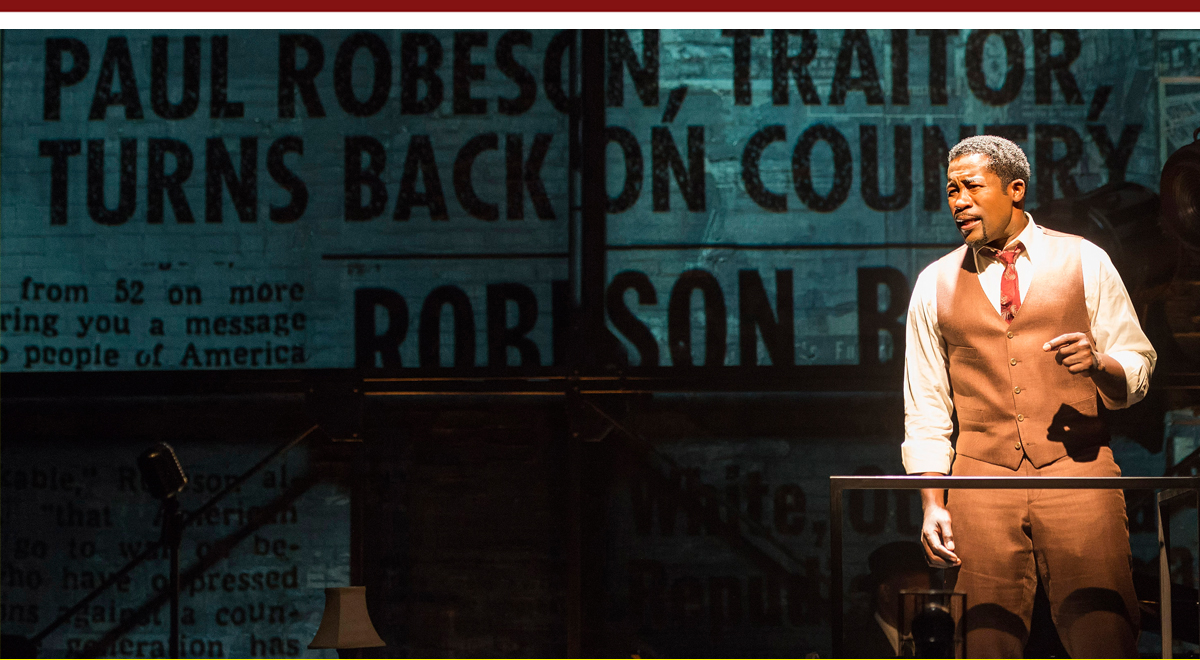

Paul Robeson had many facets. After a ground- and record-breaking run in Rutgers football he pursued and practiced law, then lateraled into a headline-making career that landed him on Broadway, in Hollywood, and briefly before Senator Joseph McCarthy's House Un-American Activities Committee. Writer-performer Daniel Beaty now offers a clear-eyed look at the man and his times in The Tallest Tree in the Forest, continuing at the Mark Taper Forum (through May 25).

Directed by Moises Kaufman, Tallest Tree is in the final leg of a world premiere collaboration with Kansas City Repertory Theatre, La Jolla Playhouse, and the Taper's Center Theatre Group. It marks Beaty's return to Los Angeles following Through The Night [REVIEW], his one-man show at the Geffen Playhouse in Spring 2010.

This production follows on the heels of Ebony Repertory's revival of Phillip Hayes Dean's Paul Robeson [REVIEW], which by comparison was a glossier portrait. Beaty explains in a program note that he "used research from a multitude of books, films and other sources. . . [and] filtered [it] through my imagination and personal understanding of this complicated man . . ." The result emphasizes Robeson's activism, joining marches and staging benefit concerts to raise funds and consciousness for civil rights and the labor movement. He also goes behind the legend for a more complete picture of the man, including the infidelity he repeated during his life-long marriage to anthropologist and author Eslanda ("Essie") Goode.

Beaty's performance strength combines a rich singing voice and split-second switches between his script's many characters. He opens the show with Robeson's signature song, "Ol' Man River" from Jerome Kern's Show Boat, not shying away from the controversial lyrics, by Oscar Hammerstein. Though used in the original 1927 Broadway premiere and the 1932 London premiere, which was Robeson's debut, references to African-Americans were successively revised beginning in 1936, with Robeson helping make those changes stick in his many concert versions.

Like Muhammed Ali and Michael Jackson generations later, Robeson, as he says in Beaty's script, "became the most well-known person in the world. They called me the Tallest Tree in the Forest." No racial qualifier was necessary for any of them. They were the most famous. While none of them had it easy, Robeson's ascent required breaking through more layers of enforced prejudice. As Beaty's character tells us, he preferred staying in England, where could simply be a member of the human race. However, when Germany began trampling vast groups of innocents, he re-embraced America as the great hope against Hitler's aggression. Unfortunately, within a decade of the end of World War II, he would again be victimized, this time by McCarthy's knuckleheads on the HUAC.

Beaty's technique of performing multiple roles – Robeson's firebrand older brother Reeve, stern but supportive father, essential and visionary wife, and various professors, journalists, and promoters – is inspired, but at times it intrudes. Kaufman does what he can to make it unobtrusive, directing the speech to the audience when possible so we are brought into the exchanges and the staccato shifts are buffered. Still, it might be more engaging if these other characters had longer, uninterrupted sections of dialogue. Obviously there are times when the back-and-forth nature of an exchange is required for a joke to land. But the exchanges are distracting.

The physical production is impressive. We are in Denny McLane's cavernous set that easily accommodates locales of theater stage and backstage, union halls, rail stations, and the expansive province of Robeson's memory. The other designers are costumer Clint Ramos, lighting designer David Lander, and sound designer Lindsay Jones. The projections of old clips and stills were compiled by John Narun. Kaufman has stationed his piano-playing music director Kenny J. Seymour in one upstage corner and the other musicians – Ginger Murphy and Glen Berger – in the other corner. The three of them produce a rich music accompaniment and underscoring.

Taken together, the Ebony Repertory and Mark Taper Forum productions are welcome reminders of Robeson's place in American history, and distinct enough to make both worthwhile.

top of page

THE TALLEST TREE IN THE FOREST

by DANIEL BEATY

directed by MOISES KAUFMAN

MARK TAPER FORUM

April 12-May 25, 2014

(Opened 4/19, Rev’d 4/24)

CAST Daniel Beaty, musicians: Kenny J. Seymour, piano; Glen Berger, woodwinds; Ginger Murphy, cello

PRODUCTION Kenny J. Seymour, music director/conductor; Denny McLane, set; Clint Ramos, costumes; David Lander, lights; Lindsay Jones, sound; John Narun, projections; David S. Franklin/Zach Kennedy, stage management

HISTORY World Premiere presentation of The Kansas City Repertory Theatre / La Jolla Playhouse Production in association with Tectonic Theater Project